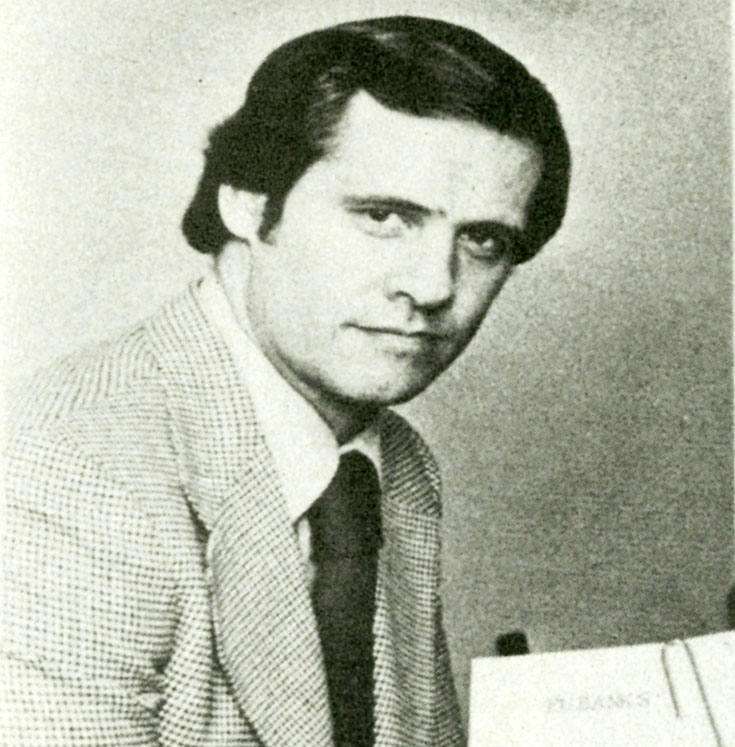

Beverly and Margaret’s cases were assigned to Criminal District Court Number 5, Judge Ed Gossett presiding; the case was handed to two of Henry Wade’ s sharpest young prosecutors — Steve Tokoly and Les Eubanks. Neither move pleased Tessmer very much. The judge who would eventually hear the case, Gossett, was one of the most popular men at the Courthouse; a spry and lively man of 72, Ed Gossett’s way with an anecdote or a quip was legend. The problem was, his shortcomings as a judge were also legend — at least among defense counsel who worked the courts. Not only was Gossett regarded as the most pro-prosecution judge among the county’s nine criminal benches, he was also known as an “old-schooler” — long on common sense, but short on knowledge of criminal law and procedure. As well-intentioned as the old fellow was, Gossett’s court generally led the other benches in conviction reversals in any given year.

The two assistant DAs presented another problem. Tokoly and Eubanks, both in their late 20s, were not yet among Henry Wade’s upper echelon of assistants, but they weren’t far away. Both were the very incarnation of Wade: handsome, strapping, tough; solid cross-examiners, good orators, excellent jury selectors. Defending Jackson — even with his solid alibi — would be no piece of cake. Both prosecutors had been reared and weaned on the Wade style: Do what it takes to get that man behind bars.

Tessmer approached the case with his typical zeal. Though considered a peer of Foreman, Haynes, Burnett and other super-defenders in Texas, Tessmer was known less for his courtroom flair than for his skill and thoroughness as a pre-trial investigator. Tessmer’s philosophy of criminal defense law was simple: An extra ounce of preparation is better than a pound of courtroom oratory or gimmickry. Courtroom dramatics had their place, of course: sometimes they were the only way to get a pro-prosecution jury’s attention. But they were generally not the stuff of which acquittals were made. Getting a man off — especially in Dallas County — rested on superior fact preparation, developing airtight material that proved the defendant’s innocence. That time-honored assumption of criminal justice — that a man is innocent until proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt by the State — was just that, an abstract assumption. In reality, securing a man’s freedom in a court of law involved proving his innocence beyond a reasonable doubt. Especially in Dallas, where District Attorney Henry Wade’s “hang ’em high” prosecutorial style has sent an average of 90 percent of all defendants to jail.

Tessmer’s object was acquittal. But in Dallas County the odds are precisely nine to one against acquittal.

First things first: Jackson’s alibi had to be solidified. That Willard and his wife claimed they were on the road back to Dallas at the time the crime occurred was all well and good; Tessmer believed them. But a jury wouldn’t. The alibi had to be buttressed by the testimony of other individuals, preferably “indifferent” witnesses, unrelated to Willard Jackson. As a defense, an alibi is a better-than-average piece of evidence; if properly supported and detailed, it can nullify one of the major cornerstones of any prosecution — placement of the defendant at the scene of the crime. But alibis are only as good as the witnesses who support them. Extensive interviewing in Austin by Tessmer and his assistants revealed at least eight individuals who could corroborate some or all of Jackson’s alibi. Unfortunately, all were either relatives or acquaintances of the defendant. Though disappointed he could not come up with an “indifferent” witness, Tessmer was encouraged by the sheer number of individuals he could call forth to support his client’s story.

The alibi broke down this way: Ann Jackson had traveled to Austin on Thanksgiving Thursday, the 25th, by bus; she arrived at 6:30 that evening. That could be corroborated by her parents, Mr. and Mrs. Emmett Earls. Willard remained in Dallas because of coaching duties at Holmes Junior High School. On November 28, a Sunday, he drove to Austin from Dallas in the couple’s gold Cutlass, arriving to join his wife at the home of her parents at 2:30 or 3 p.m. The couple ate a holiday dinner and watched television that afternoon; Ann’s folks and six relatives could substantiate that. At about six that evening, the gathering broke up. Ann and her mother took a cousin to the bus station; Willard and Emmett Earls stayed at home. The two women returned home at about 8 p.m. The four visited until 9 or 9:30, when Willard and Ann left for Dallas. They did not arrive home until 1 a.m. — a full two hours after the crime.

One major problem was that Jackson’s whereabouts between the crucial hours of 6 and 9:30 could be corroborated only by his wife and parents in law — testimony a jury might be suspicious of. Fortunately, Tessmer was able to track down a neighbor of the Earls, a Mexican-American by the name of Trelles, who said he recalled seeing Willard and Ann leave that night about 9. Apparently, Ann had backed the couple’s auto into a tree while pulling out that night, and the commotion had brought Trelles to his front porch where he observed their departure.

The alibi as solid as it could be, Tessmer turned to the matter of physical evidence. As alibis went, Jackson’s was better than average. But the only way of assuring his acquittal would be to find some tangible piece of evidence that proved he was not the assailant. Tessmer quickly reviewed the case in his mind, searching for avenues of investigation. He really had only one: the gold watch Beverly Michaels claimed the rapist took from her. If that watch could be found, it could totally clear Jackson. It had not been found at Jackson’s home by Detective Hallam, that was already established; thus, discovering it in the possession of another person, or in some pawn shop, would tend to prove Jackson did not take it. That, in turn, would prove he was not the man who attacked Beverly Michaels and Margaret Moore.

Tessmer was aware a perfunctory search through pawn shop receipts had been made by investigators in the case: but he trusted the police about as far as he could throw a squad car. It wasn’t that he felt they were dishonest, just a little less than thorough. He decided to conduct his own search for the watch. He engaged private investigators D.L. Hamer and John Barnett. His instructions to the two former Dallas policemen were simple: Re-check the pawn shop receipts at police headquarters for a 17-jewel, 14-carat gold Angelina wrist-watch; if nothing turns up there, hit the streets yourself and check the city’s major pawn shops. The watch had to be somewhere. Robbers rarely keep what they steal for very long; they fence it or hock it or sell it.

As Hamer and Barnett went in search of the watch, Tessmer sent his assistants to tidy up a couple of other loose ends in the investigation. The Sportspage was visited, employees on duty the evening of January 15 interviewed. It was established that the bar was crowded that night, that there were other black males present, that the light was dim. These were seemingly innocuous facts, but they were, in their way, significant. Any fact that might suggest that Beverly Michaels’ identification of Willard Jackson that night was made under less than ideal circumstances could cast some doubt on her reliability.

The Americana Apartments and a nearby bar, The Blue Chip Club, were checked. Had any other black males been seen in the vicinity on November 28? Finally, Tessmer obtained pictures of the defendant dating back to 1968. Beverly Michaels had been firm in her recollection that the intruder was clean-shaven; Willard Jackson wore a mustache, and according to his wife, had worn one since they’d been married in ’68. Again, a seemingly small shied of evidence. But Beverly Michaels’ almost photographic recollection of the assailant was the foundation of the prosecution’s case. They didn’t have prints to place Jackson in the apartment; they didn’t have ballistics tests to show Jackson’s .22 was the gun that almost killed Margaret Moore; they hadn’t found the watch in Jackson’s home; they hadn’t even found a green sport coat or black patent loafers. In short, the prosecution had nothing to prove Jackson was there that night except Beverly Michaels’ and Margaret Moore’s word. If one minute detail of their description of the intruder conflicted with the established appearance of Willard Jackson, it could cloud the credibility of their entire testimony — and the entire prosecution case.

By mid-February, Charles Tessmer’s defense for Willard Jackson had taken shape. It would not in any way argue that the girls had not been raped, robbed and shot. It would not argue that the crime was not savage and senseless. It would merely argue that Willard Bishop Jackson was not the man who committed the atrocities. It would rest on the defendant’s alibi that he and his wife had been returning from Austin at the hour the crimes were committed. The alibi would be buttressed by the following facts: 1) Willard Jackson has a mustache; Beverly Michaels said her assailant was clean-shaven. 2) The bar in which Jackson was identified by the victim was dark and crowded. 3) Margaret Moore had not actually ID’d Jackson in a lineup, but afterward, while looking at pictures of him. 4) No prints or ballistics proof could place Jackson at the apartment that night. All in all, the lawyer reflected, it was a pretty decent case; not airtight, but then, defenses never were. But those facts, coupled with the observation that Willard Jackson just didn’t seem to be a violent criminal personality, could be enough to establish reasonable doubt.

Tessmer was further encouraged about the case when he received the results of his motion for discovery on the prosecution’s case. In criminal law, the State can be compelled by motion of discovery to detail its case for the defense; the defense has no such obligation. That can represent a big advantage in many cases: Advance knowledge of the prosecution’s witnesses, evidence and arguments allows the defense to seek impeachment or rebuttal for the State’s claims. By the same token, if the defense develops a solid piece of physical evidence or a good witness, it can use the element of surprise on the prosecution. As Tessmer had anticipated, the State’s case consisted of two simple premises: 1) that Beverly Michaels was raped at gunpoint, then both girls were robbed and shot, and 2) that the victims had identified Willard Jackson as the man who did it. End of case. Certainly Jackson’s alibi was enough to establish reasonable doubt in the face of that.

But as February turned to March, Charles Tessmer continued to be nagged by something about the case. There just had to be something else to the matter. The search for the watch had turned up nothing. But he had a vague feeling there was another piece of evidence out there that would clear his client. Following his initial instincts about the case, Tessmer was convinced there was another young, handsome, smooth-talking black out there who had committed the crime: a man who looked enough and talked enough like Jackson to create an honest case of mistaken identity. Wouldn’t it be something, he often mused that spring, if they could actually find that man and secure his confession?

• • •

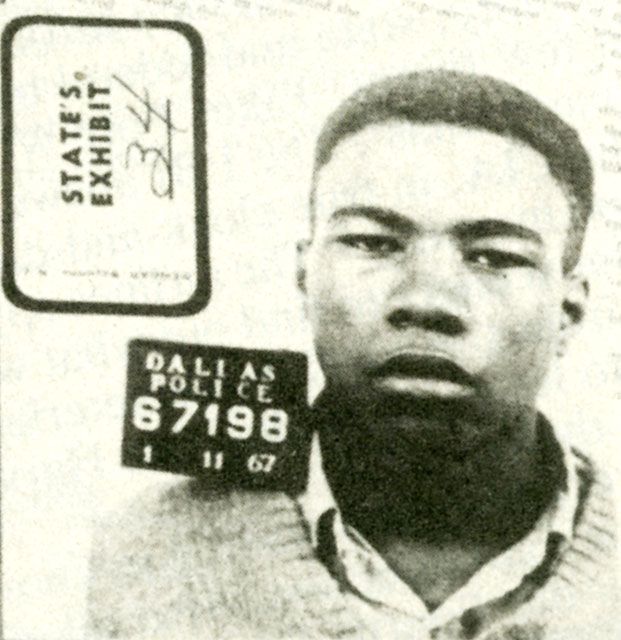

Charles Tessmer could not believe his own ears. He shook his head and scratched his curly, rust-red hair as investigator Barnett repeated his story. Barnett had been contacted by some of his sources at the Dallas County Jail, he said. To make a long story short, a young black thug by the name of John Lee Lewis had been arrested February 15 for the stabbing of two men in their Oak Lawn area apartment. He’d subsequently been linked to a handful of other violent crimes in and around the Oak Lawn area. He’d been shot in the rear of the head while struggling with a policeman the night of his arrest. While recuperating in the jail hospital, Lewis, 24, had admitted to a jailer that he had committed the crimes against Beverly Michaels and Margaret Moore.

Tessmer could still not quite believe his good fortune as Barnett raced through the details of the confession. Mistaken identity, of course, was always a part of a defense case; but nine times out of ten, it was merely a suggested possibility. Rarely did it come to fruition as a piece of evidence. Barnett said on March 14, the jailer had been talking with Lewis about several uncleared crimes of violence in the Oak Lawn area. Lewis had indicated he could clear up at least six rape/assaults in the area. He also mentioned that he always wore gloves when he went plundering. During a second discussion, Lewis added more detail: He said he’d raped a girl at the Americana Apartments on Hudnall. In a third discussion, the confession became credible. Lewis rattled off the address of the Americana Apartments and detailed certain aspects of the case. He said he’d followed a girl up to her door, asked to borrow her phone; then he’d gone into the apartment, told two girls to disrobe and raped the blonde one. Finally, Lewis said he’d shot one girl and stabbed the other when he heard her reaching for the phone.

Tessmer immediately dispatched Portnoy to interview Lewis at the county jail. The criminal’s admission to the jailer was pretty good; but he needed to be grilled about every last detail of the case. The young man’s confession was one thing; developing it into admissible, unimpeachable evidence was quite another. He was, after all, an established sociopath, a repeated felon of an unusually violent nature. Such criminals are also expert liars. Secondly, he had been shot in the head. Whether the damage affected his memory or not, it made him a questionable witness at best.

Later that week, Tessmer became more skeptical as he read the memorandum of Portnoy’s conversation with Lewis. “In my opinion, ” wrote the young attorney, “Lewis is vaguely similar in facial features to Jackson. He has approximately the same height and build. I would say that the girls could be honestly mistaken in picking Jackson. In conclusion, I would say that Lewis appears enough like Jackson so as to bring him into the courtroom during Jackson’s trial.

“I asked Lewis if he had ever been to any apartments around the Hudnall Street area, the Americana Apartments … He looked down and kept repeating, ’I don’t know, I don’t know.'” He cried throughout most of the rest of the interview. He never admitted any crimes. I got the definite impression he was lying.

“Lewis talked with little accent. He talked slowly, and his physical and mental reaction time was slow. He kept maintaining his innocence and saying ’I’m not crazy, but I must be crazy if I did the things they said I did.'”

Indeed, thought Tessmer as he tossed the memo on his cluttered desk. Certainly crazy enough to tell the jailer one thing and the attorney another. How could a jury be expected to buy the confession of a lunatic like that? The bothersome thing about it was that Tessmer tended to agree with Portnoy: Lewis was clearly lying to his assistant about having no knowledge of the Americana Apartments. Lewis was the fellow who committed the Michaels/ Moore crimes — Tessmer believed that. But acquiring his confession in a manner presentable and credible in court was another thing.

During the month of April, progress on the Lewis confession proceeded at a limp. In addition to Lewis’ lack of clarity about the confession, another problem had emerged. The defendant, facing an upcoming capital murder trial, had obtained counsel on his own. Under state bar ethics, Tessmer and company were now precluded from any further discussions with Lewis. Since no firm confession to the Michaels/Moore crimes had been obtained from Lewis, the jailer’s conversation would be all Tessmer could take to court to support his case for mistaken identity. At that, it was doubtful whether Gossett would admit it.

But the Lewis affair had produced an unexpected side benefit. Through their sources in the jail, Barnett and Hamer had managed to get wind of some statements Lewis had made concerning a gold wristwatch he’d stolen from one of his victims. From what they could gather, the watch was now in the possession of one of Lewis’ relatives, either his wife or his sister., Mary Jo Lewis of Longview. The investigators, joined by Portnoy, first visited Lewis’ house at 5002 Weonah. They did not find Lewis’ wife, but prompted by a tip that the watch was buried on the property, decided to do a little digging. Literally. Armed with spades and a metal detector, the three scoured Lewis’ backyard for at least an hour. They dug up beer cans, bottle tops, and all manner of metal junk. But no gold Angelina watch.

The next day, they visited Mary Jo Lewis in Longview. Their hearts thumped as she handed a gold watch she said Johnny had given her as a gift. Only one problem: It was a Westclox.

Despite the failure of his investigators to come up with the watch, Tessmer’s interest in it was reignited. He was more convinced than ever that the watch was the key to the case. That watch was out there somewhere, and John Lewis had something to do with wherever it was. What he needed was time, just another week, another month, to run down every conceivable possibility. But he did not have it. Already it was late June, and the trial, slated for mid-July, would be upon them in no time. Willard Jackson would have to go on trial for the rape of Beverly Michaels defended only by his own alibi. It would be simply a matter of his word against hers.

Get the D Brief Newsletter

Author