Margaret Moore was called to the stand. Eubanks skillfully guided her through her recollections of the night of November 28. She offered no conflicts whatever with Beverly’s testimony; in fact, she fleshed out some parts of the tale. Tessmer’s cross was brief. Did the assailant have a mustache? No, he did not, Margaret returned firmly. Tessmer paused to let the statement sink in. Not only was the testimony at odds with the appearance of Jackson that day in the courtroom; it was at least in subtle contrast with Beverly’s hesitant testimony on that subject. That might be worth something during final arguments. If the state’s case rested solely on the eyewitness recollections of the two victims, any conflicts between their versions could be used to raise doubt.

Lewis was brought back to court for Margaret to have a look at. She said she perhaps had been shown a picture of the man after she positively identified Willard Jackson. But now, she said, there was very little resemblance between Lewis and Jackson. Worried that the Lewis business was rapidly doing more harm than good, Tessmer took another gamble.

“Are you aware that John Lee Lewis has confessed to these crimes?” Eubanks and Tokoly nearly jumped through the ceiling objecting. The question clearly was out of the established purview of evidence in the trial. The arguing and objecting continued until late in the afternoon, when Gossett looked casually at his watch and indicated he’d had enough for the day. Eubanks again jumped from his chair and asked that Tessmer be held in contempt of court for the question. Gossett dismissed the idea with a wave of his hand, but admonished the embattled defense lawyer that such questioning was obviously in conflict with the agreed-upon limits of the trial. Tessmer nodded humbly. Deep inside, though, he was somewhat less than apologetic about the sudden question. Whatever Gossett’s ruling about the legality of the question, the jury had for the first time heard what Tessmer wanted them to hear: that John Lee Lewis had confessed to the crimes for which Willard Jackson was standing trial.

Day two of the trial was as routine as the first day had been dramatic. After perfunctory medical testimony, Eubanks called Lt. Eberhardt to the stand. The grizzled, veteran cop recounted the night of January 15, when Willard Jackson was apprehended at the Sportspage. When the witness reached the point of arrest, Eubanks tried his own gamble. He asked him what he’d told the suspect when he arrested and cuffed him.

“I told him I was a police officer and he was under arrest and he was going to have to go with us.”

“What did he reply?”

“He didn’t say anything.”

“Did this strike you as unusual?”

“Yes, sir.”

Tessmer was on his feet before the witness had even finished his words. “I object to what appeared unusual to the officer,” he boomed. “Sustained,” said Gossett evenly. Tessmer took careful mental note of the moment: Gossett had actually sustained a defense objection. Something for the scrapbook, for sure.

“In view of the nature of the question, respectfully move for a mistrial,” the attorney continued, feeling his oats. The motion was denied.

But Eubanks was not through with the matter of Jackson’s silence. He asked Eberhardt if the suspect said anything during the time he was ushered down the fire escape, into the squad car and driven to City Hall. No, he hadn’t, said Eberhardt. Tessmer was back on his feet now, ruddy face ablaze with anger. “Objection, Your Honor, that’s an attempt to use silence as affirmative evidence against the defendant.” He could not, in fact, believe that Eubanks continued to press the line of questioning. It was clearly a violation of a time-honored precept of courtroom procedure. Just as a defendant cannot be asked to incriminate himself by testimony, neither can his silence during the period following his arrest be used to imply guilt. Eubanks backed off and withdrew the question. He then concluded his questioning of Eberhardt.

“Officer, did you notice anything unusual about the defendant’s accent or lack thereof?”

“Yes, sir, when I spoke to him he did not have a southern accent.”

“Did he appear to be rather well-educated?”

“Yes.”

Eubanks passed the witness smugly. He’d made his point: The suspect Lt. Eberhardt apprehended that night at the Sportspage spoke precisely the way Beverly Michaels had described the speech of her assailant. The significance of the point was not lost on Tessmer. He stood up, buttoned the jacket of his conservative blue suit, smiled at the officer and asked:

“Well, Lt. Eberhardt, you’re not implying that all black people talk like watermelon-eating darkies, are you?”

“No, I said southern accents,” the witness said, above tittering in the gallery.

It was not an off-the-wall move. Eberhardt’s testimony made a significant point for the State. In and of itself, it corroborated the entire State case: that Beverly Michaels did, in fact, encounter the right man. With no firm rebuttal handy, a little levity was the next best antidote. Perhaps it would lead the jury to take Eberhardt’s words less seriously.

Tessmer had just two other questions for the lieutenant. From where Beverly was standing at the Sportspage, he wondered, wasn’t it true she had to look through bright blue light to the upper level where Jackson had positioned himself? True. Finally, “Did you get the names of the other black males in the place?”

“No, I did not,” replied Eberhardt.

• • •

Detective Wagoner was next on the stand. He testified concerning his discussions with Beverly at the hospital on November 29, her descriptions of the assailant, the absence of bullet hulls at the scene of the crime. Then Eubanks led him to January 16, the day he and Charles Hallam had searched the Jackson home and brought back a .22, a .38 and a man’s belt. Pass the witness.

“When you searched the Jackson home,” Tessmer began his cross, “you didn’t see and bring back a dark, solid green sportcoat, did you sir?”

“No sir, I don’t recall.”

“Did you see a black pair of slacks?”

“No sir.”

“Let’s get down to some shoes. Did you see and bring back a pair of shiny black shoes with silver buckles?”

“No sir.”

Tessmer paused once again to let it all sink in. If the State was going to make a point of the fact that two items were found in Jackson’s home resembling the paraphernalia of the Michaels/Moore assailant, then he could damned sure point out that at least three other items of clothing specifically described by the victims were not found.

Then he turned to the crime lab testing on Jackson’s black leather gloves. Wagoner had testified on direct that he had taken the gloves to Louie Anderson for blood testing.

“You didn’t request any test of these black gloves to determine whether they had nitrates on them?”

“No sir.”

“In other words, there was no request made to determine if these gloves were worn by a man firing this gun, as to whether there were nitrates on them?”

“No sir.”

Another good point. Nitrate testing might have proven that the gloves had, in fact, been worn by a man who’d fired a gun recently. Tessmer wanted the jury to wonder why the State had not performed such tests.

He concluded. “All right, now sir, once again, the only objects you brought back from the search waiver were a .22 caliber gun, a .38 gun, some ammunition and a belt with what you think was a gold buckle?”

“Yes.”

“No knives?”

“No knife, sir.”

“No dark green coat?”

“No dark green coat.”

“No black trousers?”

“No black trousers.”

“No shiny shoes with silver buckles?”

“No sir.”

“Pass the witness.”

Eubanks moved Wagoner to the lineups during redirect examination. He asked the detective to describe the condition of the lineup room the morning Margaret Moore viewed Willard Jackson. “The light was bad,” he said. “There were bulbs out. I would say the room, under the conditions, was very bad.” Wagoner continued that Ms. Moore could not make a “100 percent” sure ID from the lineup, so they retired to view some pictures. Which picture did she choose, Eubanks asked. As Wagoner began to indicate the picture of Willard Jackson sitting down, Tessmer leapt to his feet. “Objection!” he said. “That’s bolstering an unimpeached witness.” Gossett overruled. “Note our exception,” Tessmer concluded.

“Bolstering” is a common error made in trial law, meaning counsel has attempted to repeat the testimony of a primary witness (in this case, Margaret Moore) through a hearsay witness — improper procedure if the original testimony of the primary witness has not been impeached. Tessmer’s objection and exception were standard procedure. Like any defense attorney’s, his primary object was acquittal. But in Dallas County, the odds are precisely nine to one against securing acquittal. The next hope of the defense is appeal. The more exceptions to a judge’s actions a defense counsel can cram into the record, the better the chance he has for a reversal of the conviction and a new trial for his client. The bolstering charge was the first of a myriad of exceptions Tessmer would make.

Tessmer had one last set of questions for Wagoner on re-cross examination. He wanted to know more about the set of pictures Margaret Moore viewed following the second lineup.

“Who was present at the picture show up besides you and Miss Moore?”

“Myself, Miss Moore and Miss Michaels, I believe…”

“Oh, Miss — would that be Beverly Michaels?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Did she have anything to say about the photographs? She did, didn’t she?”

“Well, there was some conversation there. I know that.”

Point one established. On to point two.

“So two [pictures] of Willard Bishop Jackson were shown to her along with four others, right?”

“Three others.”

“All right. And isn’t it a fact that State’s Exhibit 3 has Willard Jackson’s name written on the back of it and the rest are blank?”

“Yes, sir.”

“I suppose you’re going to tell us somebody wrote his name on there after she picked it out, yes or no?”

Wagner demurred.

“So actually, we have two pictures of Jackson alone and on Defense Exhibits 8, 10 and 11, pictures of lineups that Jackson is in every one of them.”

“Yes, sir.”

“So he’s in all five of them?”

“Yes, sir.”

“You figure that’s fair identification procedure?”

“I think under the circumstances it was, yes, sir.”

“Would that be like dressing a man up in a red suit and asking, ’which one is Santa Claus?’”

“No.”

“No further questions.”

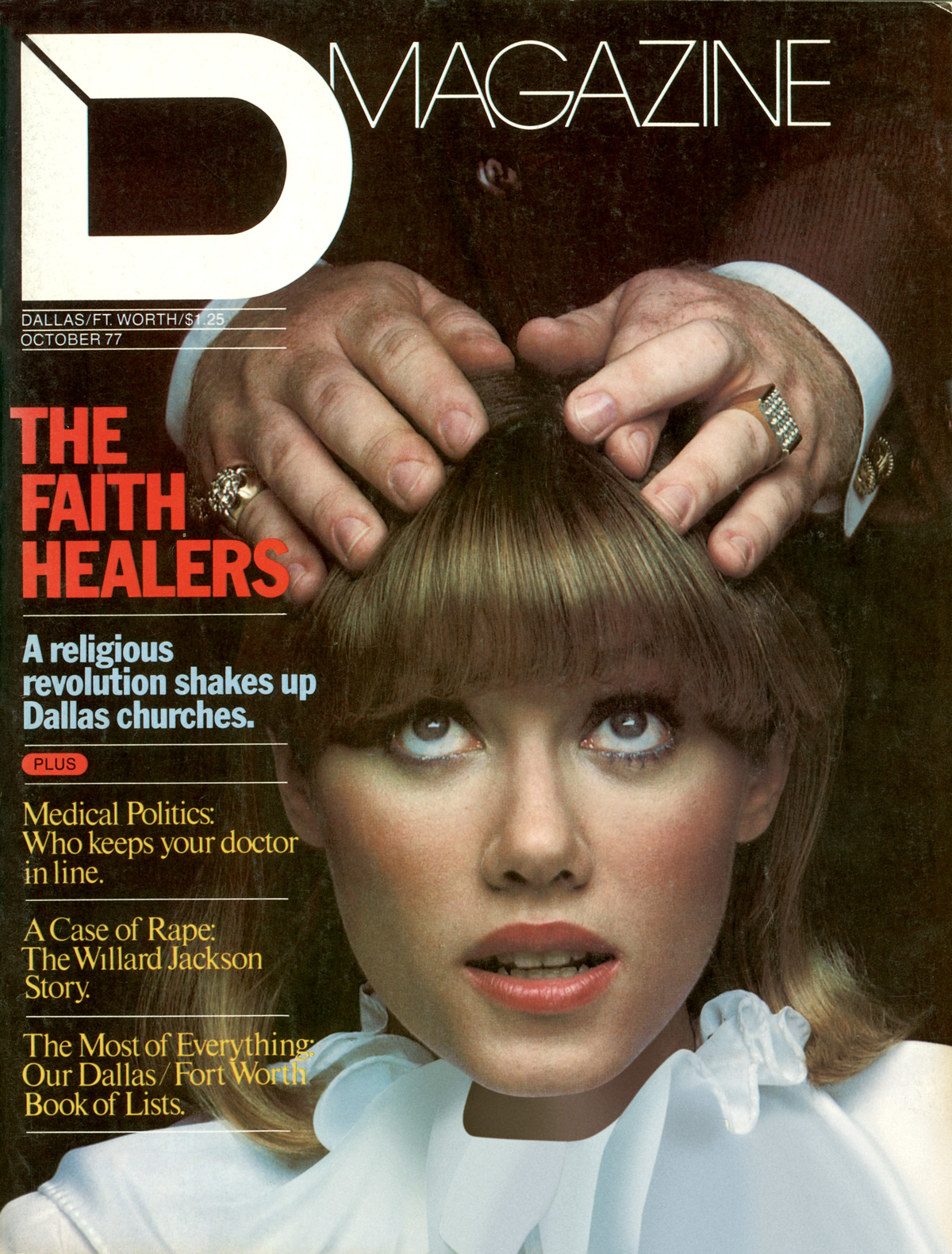

The State finished the major portion of its case the next day, with the routine testimony of Detective Hallam and Louie Anderson, the crime lab chemist. Tessmer found little of use here on cross-examination, except the highly interesting admission of Anderson that the speck of blood he found on one of Jackson’s leather gloves did not appear to be in a spot where blood would land during a stabbing. Following a recess, Tessmer introduced the case for the defense. The case would be simple, he told the jury. He would prove that Willard Bishop Jackson was not the right man because he had not been in Dallas on the night in question. He would additionally show evidence to the effect that another black individual resembling Willard Jackson committed the crimes. He would introduce nearly 20 character witnesses to attest to Jackson’s law-abiding nature.

Before calling his laundry list of alibi witnesses, Tessmer had to argue before the court over the admissibility of two witnesses who were prepared to testify to the mistaken identity defense. One was the jailer who heard John Lee Lewis confess to the Jackson rapes in the County Jail. The other was Thomas Gunn, an ID officer with the sheriff’s office. This was a piece of testimony Tessmer’s investigators had come up with at the 11th hour: It seemed that following Jackson’s arrest January 15, the sheriff’s department had been requested to place Jackson in a lineup concerning the rape of a Longview woman and the assault of her husband in mid-December. Apparently, the assailant was said to resemble Jackson. From the lineup, the husband had ID’d Jackson as a “possible.” Later, the husband had recanted on his ID of Jackson and had tentatively identified a photo of John Lee Lewis, as had four other witnesses. Charges in the Longview rape were now pending for John Lee Lewis. Tessmer was prepared to introduce Gunn’s testimony regarding the facts of the lineup.

Clearly, both bits of evidence were significant to the defense of Willard Jackson. The jailer’s testimony, of course, would show that another criminal — one who Beverly Michaels had already said resembled Jackson — had confessed, in part, to the crimes in question. The Longview testimony would go a step further in the mistaken identity defense: The husband’s confusion between Jackson and Lewis would establish clear precedent for confusion between the two men.

But there were strenuous objections by the prosecution outside the presence of the jury. The prosecution’s point of view was simple and compelling: The jailer’s testimony was hearsay of the rankest order: if Tessmer wanted to build his mistaken identity case around Lewis, let him put the fellow on the stand himself.

Tessmer rebutted that the jailer’s testimony went to the heart of the defense case — mistaken identity. Gossett listened impatiently, then with little hesitation ruled that the testimony would be heard outside the presence of the jury. “Exception,” noted Tessmer.

As for the Longview lineup testimony, Eubanks and Tokoly argued that it simply wasn’t relevant, it ran “too far afield.” Tessmer reiterated his argument that it went to the heart and soul of the defense case. Gossett ruled in favor of the prosecution with another quick swipe: “That’s a rather lefthanded way of proving the fallibility of the girls’ identification,” he told Tessmer.

Both the jailer and Gunn were brought in outside the presence of the jury and testified for the record. Although extremely disappointed that an entire block of his defense case would not be heard by the jury, Tessmer considered the matter a half-victory: At least if the jury couldn’t hear the mistaken identity testimony, the Court of Criminal Appeals could. Somewhere in that series of rulings made by Gossett, there had to be a reversible error. The present defense of Willard Jackson, however, had been seriously crippled from the outset.

His aces in the hole gone, Tessmer turned to all he had left: the alibi. One by one, he paraded Willard Jackson’s Austin relatives to the stand to prove the defendant had been on the road back to Dallas at the time the attack occurred. Eight, including Ann Jackson, testified to parts or all of the Austin alibi.

The neighbor Trelles told the jury that he’d heard a car back into a tree that evening, and that from his front porch he saw some commotion in the Earls’ front yard. He had not actually seen Willard and Ann, only Ann’s father and some other individuals. Mrs. Jim Hutchins, another neighbor, testified that when she returned to her home before going to work that night about 9, she saw Ann and Willard in the Earls’ front yard. Finally, Ernestine Moten, a Dallas friend of Ann’s, testified that she’d called Ann Jackson about 1 a.m. on the 29th. Ann had answered, saying the couple had just gotten in from Austin.

Throughout the alibi testimony, prosecutors Tokoly and Eubanks were surprisingly calm. They made insinuations that the whole story had been coached into the witnesses; stressed the fact that the only people who could testify to Jackson’s whereabouts between 5:30 and 9p.m. were the defendant and his immediate family. But, all in all, they offered little in the way of rebuttal.

The alibi established, Tessmer turned to his most important witness: Willard Bishop Jackson. This too, the attorney realized, was a calculated risk. Often in criminal cases, particularly rape cases, the defense will elect to keep the defendant off the stand. Even with a reasonably credible defendant, the risk that he will say something damaging on cross-examination is generally too high. But this case was different: The prosecution rested its case on the credibility of Beverly Michaels and Margaret Moore; since they were unimpeachable, the best way to rebut them was to establish the credibility of Willard Jackson. Certainly Jackson was an ideal defendant to work with: Sober, articulate, well-mannered; he did not look like a man capable of the crimes on trial. Tessmer very much wanted the jury to see that too.

Jackson took the stand confidently, dressed conservatively in gray suit and tie. Tessmer wasted no time. “Willard, you’re charged here by indictment with having carnal knowledge of a young lady by the name of Michaels; are you guilty of that charge?”

“Not guilty,” Jackson returned evenly. Tessmer was pleased: As protestations of innocence went, Jackson’s was solid. He then asked the defendant what the Jacksons’ joint monthly income had been in late 1971. Jackson replied, “Somewhere around twelve hundred.” Tessmer wanted that in the record for future use. He would later argue to the jury that a man of those means wouldn’t roam around robbing young ladies of $50 or so. He had no motive.

Tessmer then slowly guided Jackson through the alibi defense. Jackson reiterated the alibi of his wife and seven relatives.

Tessmer moved to Jackson’s work as a junior high coach. He established for the jury that the defendant’s job involved working with young boys, that he’d coached several all-state players, that Holmes Junior High was a racially-mixed school. Then he asked Jackson: “Willard, how long have you worn a mustache?” “Since 1968,” the defendant replied without blinking.

“Willard, how far is the Sportspage from the Americana Apartments, do you have any knowledge of that?”

“No knowledge whatsoever.”

Tessmer quickly interjected a non sequitur question for effect: “Were you with your wife all of the time between 9:45 p.m. November 28 and 1 a.m. of November 29, when you got to Dallas in your automobile?”

“Yes, I was.”

Back to the Sportspage.

“All right. Now, would you mind to mark where you were when you first noticed some young lady looking at you?”

“No, I never noticed anybody looking at me.”

“Never did?”

“No.”

Tessmer paused. He hoped the point had not been lost on the jury: Here was a direct contradiction of Beverly Michaels’ testimony.

Tessmer: “Have you ever before seen Beverly Michaels before this trial again and before your arrest the night of January 15, 1972?”

Jackson: “No, I have not.”

“Have you ever seen Margaret Moore before the night of January 15 or 16 of ’72 or during this trial?”

“No, I have not.”

“Are you the man that shot those two women?”

“I’m not the man.”

“Are you the man that robbed them of some $40 or $50?”

“No, I’m not the man.”

Tessmer quickly established that his client had voluntarily signed search waivers of his home, that at the time he signed them, he had no idea what sort of evidence the police were after. He moved through the physical evidence at issue: “I will ask you whether or not you have ever owned a dark green sport coat?”

“No.”

“Have you ever had any black trousers?”

“I do have some black trousers.”

“Have you ever owned any shiny black shoes with silver buckles?”

“No.”

“Have you ever owned a belt with a shiny silver buckle?”

“No.”

“Have you told this jury the truth?”

“Yes.”

Tessmer passed Jackson, eminently satisfied with his first round of testimony. In a circumstantial trial like this, it was as good as the defense could hope for.

Steve Tokoly, dark eyes glinting behind wire-rimmed glasses, pressed the defendant hard, zeroing in on the Sportspage.

“Did you ever look at a white girl in there?”

Jackson: “Oh, there were several in there.”

“Did you look at one several times?”

“No, not as I recall.”

“So, if Beverly Michaels said that she noticed you because you were looking at her several times, that would be a lie?”

“Yes, it was.”

Tessmer objected. “We object to him comparing testimony Your Honor.” “Overruled.” But the defense attorney was worried about more than Tokoly’s methods: Willard’s statement that Beverly Michaels must have been lying could be damaging to his client. After all, it was well and good to establish Willard”s credibility, to show the jury he wasn’t the sort capable of these crimes. But to call a young lady who’d been the victim of a savage crime a liar was something else. The jury just might get protective of her.

Tessmer cleared up the matter on redirect by establishing that Jackson might have looked at several girls.

All in all, Tessmer was reasonably optimistic as he rested his defense. Certainly he’d felt worse at this stage in other cases. As impressive as it was, the prosecution case still cried out for some physical evidence to link Jackson to the crime. His defense case, while weakened by Gossett’s rulings against additional testimony, had held up well. The alibi had not been substantially impeached by Tokoly and Eubanks; Willard had been firm and impressive on the stand; he’d established some doubt about the girls’ story with the mustache evidence and other tangential points.

Get the D Brief Newsletter

Author