“Take care of your brother. We have to go.”

In 1968, 12-year-old Angel Ruiz heard those words from his father, who had awakened him and his 8-year-old brother, Carlos, in the middle of the night as they slept on the floor of Cuba’s Havana Airport. The father told the boys that he and their mother were being taken away for searches they had to undergo as part of a program to get the family out of the country that Fidel Castro controlled. He added that he did not know exactly why they were being taken—or whether the boys would ever see them again.

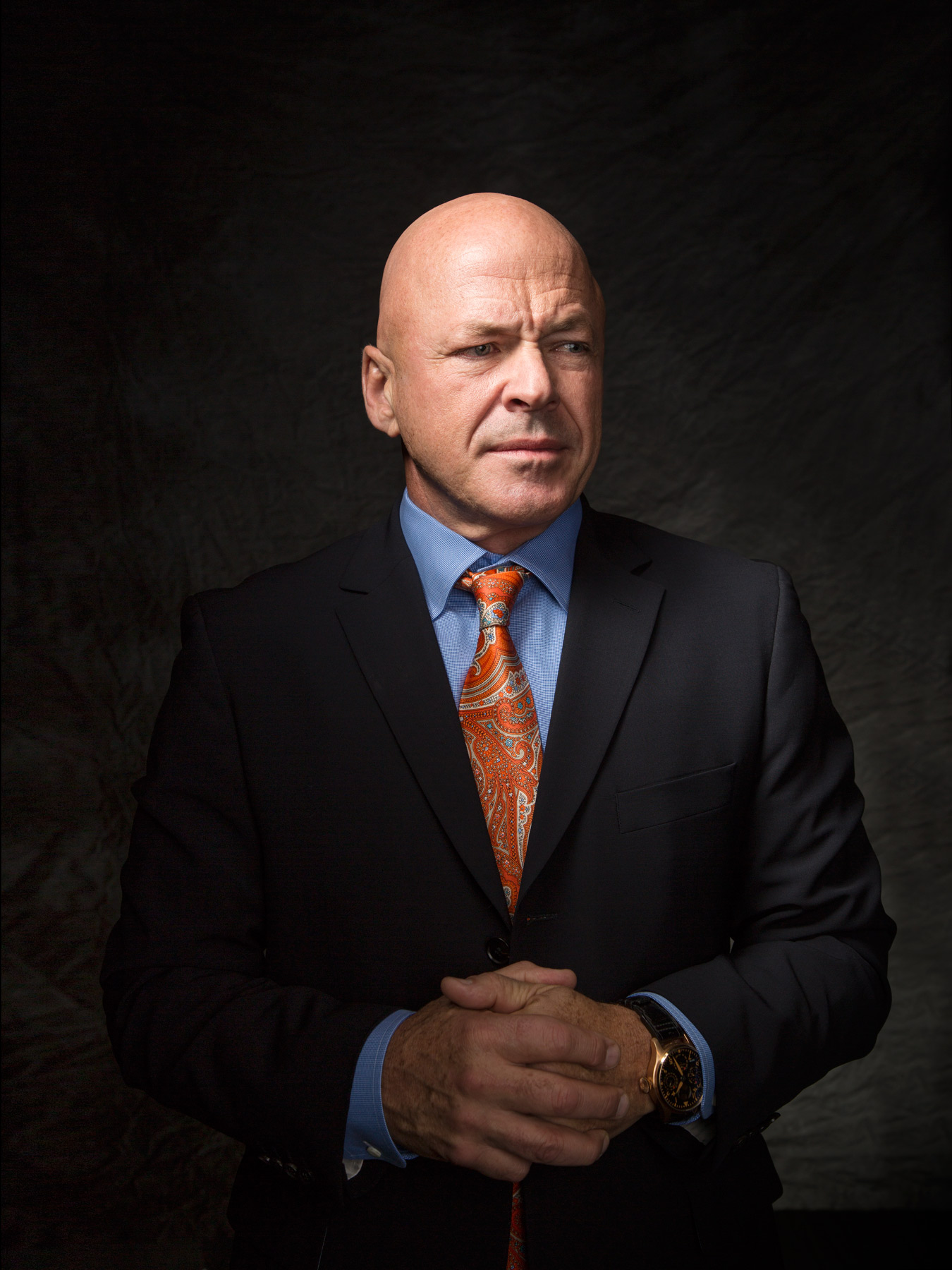

Nearly five decades later, that 12-year-old boy now runs a large portion of the U.S. and Canada operations of Sweden-based Ericsson, one of the two biggest suppliers of hardware and software used in telecommunications networks of companies like Verizon and Dallas-based AT&T. (The other dominant player is Nokia.) Of Ericsson’s roughly 16,000 North American employees, 9,500 report to Ruiz, including most of the 3,600-plus people at the company’s North American headquarters in Plano. The 59-year-old leader, whose title is head of Ericsson Region North America, saw annual revenue for his piece of the company hit $8 billion in 2014—compared with $500 million when he took the helm in 2001.

Along the way, Ruiz spearheaded Ericsson’s move into services that included signing a first-of-its-kind deal in the U.S. in 2009, when the nation’s No. 3 wireless telecom company, Sprint, agreed to pay up to $5 billion to have Ericsson run its network.

Along the way, though, Ruiz has faced monumental challenges. In business, he had to steer Ericsson operations through the telecom bust that began near the turn of the century. On the personal side, he fought a lengthy, brutal battle with an “incurable” disease. Through it all, Ruiz has survived and triumphed—a fact that does not surprise those who know him.

Hans Vestberg, the Stockholm, Sweden-based president and CEO of Ericsson, actually worked for Ruiz from 2001 to 2002, when Vestberg was chief financial officer of the company’s North American operations. “He was a demanding leader, but also a great mentor, and I learned a lot,” Vestberg says. “Today, he is on my global leadership team … I believe that his dedication and hard work have contributed to Ericsson’s leading position in North America today.”

•••

Though today he rubs elbows with some of the world’s top telecom executives, Ruiz’s start in life was anything but glamorous. He was born into a lower-middle-income family in Cuba in 1956, about three years before Castro seized power. Like most Cubans of that era, the Ruiz clan led a hardscrabble life under Castro, living with Angel’s grandparents in the island nation’s western province, known as “Pinar del Rio,” or “River of Pines.”

In part because of the weakness of the Cuban peso, Angel’s grandfather supplemented his meager income from driving a bus by bartering for food and other goods with passengers, offering rice that was used to feed chickens for whatever he could get in return. “They gave us one meal a day,” Ruiz says of his grandparents.

His father, Angel Arturo Ruiz, worked as a warehouse supervisor for International Telephone and Telegraph Corp., or ITT, an American firm that controlled Cuba’s telephone company until Castro seized the Cuban operation in 1960. In addition to economic issues, violence was a problem for those living in Cuba. Ruiz remembers his father pulling him to safety when gunshots rang out outside their home. He also recalls the entire country going on alert during the Bay of Pigs invasion and the Cuban missile crisis. “It was very trying,” he says.

Following the Bay of Pigs incident, Castro opened the doors for families to leave the island if they so desired. Angel Arturo filed paperwork in 1963 for himself, his wife, Brunilda, and his children to relocate to the United States. Almost as soon as the ink was dry on the filings, Angel Arturo lost his job at the ITT operation. While the family’s exit application wound its way through the system over the next several years, Angel Arturo earned what he could doing manual labor and construction work. This included being shipped by the Cuban government to the country’s other provinces, where he would work for weeks or months at a time, cutting sugar cane for meager or no wages.

The government made life tough for the family in other ways as well. As in most neighborhoods across the island, the communist party employed an individual or family in the Ruiz clan’s area to keep an eye on the residents. By seeking an exit permit, “they singled you out” for additional scrutiny, Ruiz recalls. The family also got hit with a pejorative label for anyone perceived as a traitor to the Castro regime: “We were called ‘worms,’” Ruiz says.

It took five years to get the necessary approvals to leave the country. When the time came to head for the airport, the family brought little more than a bag of clothes to take to America. The boys’ uncle drove them roughly 60 to 100 miles to get to the Havana airport. Ruiz remembers his uncle scrambling to get gas for the journey, which was one of the first times Angel and his brother Carlos had ridden in a car.

Once they arrived at the airport, they wound up waiting about 36 hours to fly out of Cuba. That was when Castro officials came for Angel Arturo and Brunilda in the middle of the night. “Having my parents taken away, I can’t give you a specific time frame, but it felt like forever. It felt like ages,” says Carlos Ruiz, who’s now a mechanical technician at Universal Studios in Orlando, Florida.

Ultimately, the government let the couple return to young Angel and Carlos—but only after first subjecting the adults to body cavity searches. The boys, too young to understand what had happened, instead became entranced with the new experiences the U.S. had to offer once the family arrived in Miami. “I had a great ham sandwich,” Angel recalls. “And a Coke.” Carlos, meanwhile, remembers peering into a vending machine and seeing a pack of Wrigley’s chewing gum. “We didn’t have that in Cuba,” he says. “I’ll never forget it.”

•••

The Ruiz family settled in Baltimore, where they lived with one of the boys’ aunts on the maternal side of the family. Their father worked as a supervisor at a spice company in Maryland, while Brunilda took a job in a factory that made synthetic flowers.

Carlos believes his brother inherited their father’s aptitude for numbers and all things mechanical, and his will and determination from their mother. At one point, for example, Brunilda decided she wanted to earn a cosmetologist’s certificate. It involved passing a test in dermatology in English, which she didn’t speak. So, she got hold of a textbook and memorized answers based on how the questions looked on the page, even though she didn’t understand them. She passed the test, Angel says, spreading his thumb and forefinger on one hand about an inch apart as he recounts the story. “The book was this thick,” he says. In later years, he adds, Brunilda became the primary breadwinner in the family, running a successful beauty salon in Winter Park, Florida, for 20 years.

Long before his parents settled for good in Orlando in the early 1980s, Angel displayed signs of having his mother’s aptitude for business. Earning $2.30 an hour driving forklifts and unloading tractor-trailers part-time at the same spice company where his father worked, Angel managed to pay off a Chevrolet Impala in two years. He later got an opportunity grant to help pay for his electrical engineering studies at Florida Technological University (now the University of Central Florida). But he still had to work odd jobs to make ends meet. Those gigs ranged from selling shoes at JCPenney and sporting goods at Montgomery Ward to unloading huge baskets of soiled hospital linens at a laundromat. The work that paid the best was at a large parcel-delivery company, where Ruiz received $8 an hour for a shift that ran from 11 p.m. to 2 a.m. “It was like a football practice,” he says. “You were unloading trucks as fast as you could, and there was a guy screaming.”After a doctor told Ruiz he did not think the executive’s body could take any more, Ruiz responded: “Let me be the judge of that.”

After graduating from Florida Technological in 1978, Ruiz put his degree to work with jobs in the electrical department at Bethlehem Steel and, while later employed at Computer Sciences Corp., as a hardware engineer at the Kennedy Space Center on NASA’s space shuttles. Perhaps the best on-the-job education he received, though, was at C&P of Maryland, a telecom company. Working as an engineering supervisor there, the 24-year-old Ruiz found himself overseeing a unionized work crew, some of whose members were in their 50s and 60s. Productivity was an issue in the crew, but union guidelines made motivating and penalizing its members difficult. “I couldn’t pick up a tool or they’d file a grievance” and claim the boss was trying to do their work, Ruiz says.

That didn’t stop Ruiz from trying to prod more work out of the group, something that did not always sit well with the two union stewards that were part of it. On at least two occasions, “they wanted to take me outside and beat me up,” he says. After that, Ruiz began to assume more senior roles in his jobs, which included working as a project manager at the old DSC Communications in Plano. He joined Ericsson in 1990 as a senior project manager.

•••

By the fall of 2000 Ruiz was living in Atlanta, where he was calling on Cingular Wireless, a cell phone services provider that’s now part of AT&T. In September of that year, he began to notice blood in his stool. For insurance reasons, Ruiz’s doctor performed a procedure called a sigmoidoscopy, which searches for problems like cancer in a more limited part of the body than a colonoscopy. It costs about three times as much. The conclusion of the procedure, though unpleasant, was not the end of the world. Ruiz had hemorrhoids, the doctor told him.

Yet the symptoms persisted. Then, at a family gathering for Christmas in Orlando, Ruiz’s mother disclosed to him for the first time that seven of her nine siblings had died of cancer, along with her mother. Though Ruiz concedes he was initially upset with his mother—“It could have killed me,” he says—he also understands her reluctance to discuss the matter. Like many Cubans of their generation, Ruiz’s parents were brought up to avoid disclosing health issues like that, concerned that it would show weakness in their families.

After returning to Atlanta, Ruiz forced the issue with his physician and the insurance company. The resulting colonoscopy found a colon tumor located three centimeters above where the sigmoidoscopy had stopped. The cancer was at stage 3, meaning it was becoming large and had spread into Ruiz’s lymph nodes. Surgery the following day removed 25 lymph nodes, of which 15 were cancer-infected, along with a foot-long section of Ruiz’s colon.

Ruiz’s doctor later advised him to enlist the most aggressive cancer doctor he could find, and recommended an Atlanta oncologist, Dr. Carlos Franco. When the Ericsson executive called Franco’s office to make an appointment, though, the doctor’s assistant told him the doctor was too busy to see him. Ruiz called back later and told the person who answered that he was a relative of Franco’s visiting from out of town. When Franco came to the phone, Ruiz ‘fessed up. That amused Franco, who agreed to see him.

Despite the seriousness of the situation, Ruiz remained upbeat, those close to him say. Scott Boxer, a North Texas business executive who lives in the same Frisco neighborhood as Ruiz, found his fellow car and Harley-Davidson enthusiast similarly outgoing during a separate battle Ruiz faced with back issues. “You’d never know there was a problem,” says Boxer, who runs Plano-based Service Experts Heating and Air Conditioning LLC. “No matter how much pain he is in, or the issue he’s dealing with, he’s outgoing, positive, and has a fun-loving attitude.”

That attitude spills over to Ruiz’s work. Gowton Achaibar, who works for Ruiz as chief information officer and head of engagement practices for Ericsson in North America, notes that his boss had surgery in February 2015 on his back. “He was climbing canyon walls in Arizona by September,” Achaibar says. “He thinks of it as nothing.”

•••

Although Ruiz may not have necessarily let on to the outside world the gravity of his cancer issue, he approached his battle with the illness as something approaching a war. “I got very angry with the disease,” he says. “I became obsessed with how to beat it.” Franco recommended that Ruiz try a potent anti-cancer drug called LPT 11, for which Franco was conducting a clinical trial. The only catch was that a computer program had to randomly select Ruiz to be part of the trial. “Of course,” Ruiz says, “it did not.”

So, Ruiz reached out to Linda Armstrong, mother of cancer survivor and now-disgraced cycling champion Lance Armstrong. With the help of Linda, who had worked for Ruiz at Ericsson, he got in touch with doctors that had treated her son. “I used them to force Dr. Franco to put me in the study,” Ruiz says.

That success was something of a mixed blessing. LPT 11 brought on such severe dehydration, through vomiting and diarrhea, that some children and elderly participants in the trial wound up dying, later forcing cancellation of the trial. Nonetheless, Franco and Ruiz decided together the executive would receive 24 treatments of a three-drug chemotherapy cocktail that included LPT 11.

Franco’s philosophy was to put Ruiz’s body through the toughest regimen of chemotherapy, giving Ruiz the best chance of wiping out the cancer and ensuring it did not spread or return later. Soon afterward, Ruiz began going to a cancer clinic on Friday mornings. There, he would spend two hours having roughly half-a-gallon of the poisonous drug combination pumped into him intravenously.

The side effects came fast and hard. After the first two treatments, Ruiz suffered a dramatic drop in his hemoglobin, the protein molecule in red blood cells that moves oxygen from the lungs to the rest of the body. As a result, the remaining treatments had to be spread out over nine months. Even then, Ruiz would spend Friday afternoons following the treatments curled on the floor of his bathroom with muscle spasms in his torso stemming from all the vomiting he was doing. It got so bad that he would start to gag just from walking into the clinic for his Friday morning treatments.

Ruiz’s wife of 33 years, Miriam, remembers Dr. Franco telling her husband at one point that he did not think the executive’s body could take any more. And she remembers her husband’s reply: “Let me be the judge of that.”

The optimism and determination Ruiz displayed in combating cancer may have rubbed off on his then-teenaged children—Desiree, now 29, and Arius, now 26. Miriam would take the kids out to do fun things on the afternoons of her husband’s Friday cancer treatments, so he could be at the house alone to deal with the side effects. Even though she, her daughter, and her son all knew what was happening back home, the kids never displayed any sign that they were worried about him possibly succumbing to cancer, Miriam says. “When I would ask them, they would just say, “I know he’s going to be OK,’” she says.

•••

Through it all, Ruiz kept working hard at Ericsson, partly as a way to keep his mind off the cancer. His diligence at Ericsson even helped lead to a promotion to his current role in September 2001, three months before the chemotherapy treatments ended. Even by Ruiz’s hard-driving standards, people around him were taken aback that he was able to balance executive life and a successful fight against the disease. “I was amazed,” says Jose Farinas, a Florida-based sales director at a telecom company who has been friends with Ruiz since college. “He set his goal, and nothing was going to stop him.”

Soon, however, Ruiz was grappling with an entirely different problem: a rapidly declining market for telecom equipment. With spending by large telecom companies falling off a cliff, Ericsson, like every other member of its industry, had to take extraordinary steps to survive. As a result, Ericsson saw its North American headcount shrink from 10,000 at the time of Ruiz’s promotion to closer to 4,000 within two years. Ruiz was forced to reduce his unit’s workforce in that time frame from 3,600 to 1,154. “We were laying off people left and right,” he says.

More than a decade after those trying times, the 10 players that once played in the sandbox that Ericsson shares on these shores will have shrunk to just two in the first half of 2016. That’s when dominant Ericsson rival Nokia is expected to complete a roughly $16.8 billion acquisition of Alcatel-Lucent. Ruiz has helped ensure his business is one of the survivors. He’s done it by being a leader in pushing Ericsson to offer a broader range of services that help telecom carriers get the most out of their networks—monetarily and otherwise.

When Ruiz took his current post, roughly 90 percent of his business unit’s revenue came from selling hardware and software, with services the remainder. Today, products and services each account for about half of a revenue pie that has grown roughly 16-fold under his leadership. Ericsson’s move into services is a major reason the company inked a partnership in November with Cisco Systems, a large maker of Internet equipment. The complex deal reportedly will bring together some of the companies’ sales and consulting services, and may lead to the joint development of new products. Cisco and Ericsson, which will bring its expertise in wireless to the table in the deal, both expect the alliance will add about $1 billion in revenue to each company’s annual revenue by 2018.

The secret behind Ruiz’s success, fellow Ericsson executives say, is his focus on operations, along with his understanding of customers. “At the end of the day, you can have all the strategy you want,” says Per Borgklint, a peer of Ruiz’s who runs a separate, California-based global Ericsson unit. “But the success of a strategy is 98 percent based on execution. That’s what he’s extremely good at—executing, getting things done.”

With his 60th birthday approaching in March, Ruiz isn’t entirely sure what the future holds for him. “My wife says that if I retired, I would drive her crazy. I have to agree with her,” he says. “I’m not ready to retire, whether at Ericsson or someplace else. I enjoy what I do. I enjoy going to work.”