Before there was Shingle Mountain, there was the Deepwood dump. The illegal dumping grounds in southern Dallas collected tons of trash and construction debris for 25 years; a judge finally ordered the city to clean up the site in the late ’90s. The closed landfill then became a “visionary restoration project that reclaimed 120 acres of the Great Trinity River Corridor,” according to the Trinity River Audubon Center, the nature center that opened at the site in 2008.

The landfill was a “quintessential example of environmental injustice,” says Ben Sandifer, the naturalist and environmental watchdog who knows southern Dallas’ Great Trinity Forest as well as anybody alive. It was a quarter-century episode in a long series of neglect, which saw a predominantly Black community subjected to toxic pollution and ignored by the city.

“The city of Dallas was one of the principal parties responsible for the damage and pollution there,” he says. “The thought process was that they were going to remediate the site and turn it into something that would become an eco-tourism destination, not just for the city, but regionally. I think [the Audubon Center] has done an excellent job of doing that. Tens of thousands of schoolchildren have gone through that property and learned about their own backyards, the land that represents nature here in Dallas.”

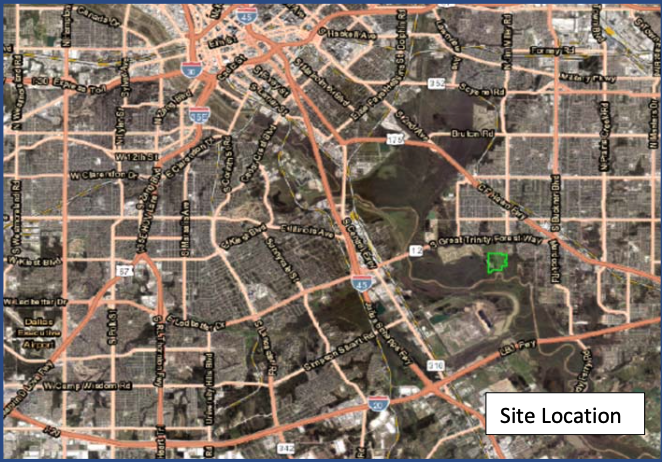

Sandifer is worried that will change, and he’s sounding the alarm about the possibility the city will redevelop 75 acres there for a solar farm. In total, the land spans 128 acres and includes the old Deepwood landfill as well as the neighboring Loop 12 landfill, which is also closed. Dallas is now accepting proposals on the project, which would “decrease energy burden among [lower and middle-income households] and increase renewable energy generation in Dallas,” according to a city document asking for potential vendors to submit their plans. It would also, Sandifer says, harm the wildlife habitat and nature center that have risen in place of the old Deepwood landfill.

The city didn’t answer my questions about the Deepwood solar project last week. In an email, Shelly White, the director of the Trinity River Audubon Center, says that the “City of Dallas is an important partner to Trinity River Audubon Center, and I am gathering information about this project so that my team and I may determine the habitat and wildlife impact.” A newly elected City Council member tweeted that nothing “will move forward without Environmental Commission review and City Council approval.”

The City Council’s environment and sustainability committee was briefed in June on Dallas’ solar plans. Katy Evans, climate coordinator for the city’s office of environmental quality and sustainability, told council members at the time about several projects pushing renewable energy, including loans for solar panel installation at homes and such. The city budget for 2020-2021 includes about $250,000 for developing “community solar,” according to her presentation.

Evans also discussed the possible solar farm at the Deepwood landfill, noting that the city would seek developers who could finance, develop, and operate the site themselves, with the affordable energy generated benefiting low-income residents in “adjacent neighborhoods” in southern Dallas.

“It is a fantastic property for community solar,” Evans told council members in June. “In fact, on the east side of this, we could construct it in a way that wouldn’t take away from the vistas and the experience of the nature center. So we’re really optimistic we could get between 8 and 15 megawatts on the site.”

For reference, Evans said, 1 megawatt on a peak demand day in the summer could power about 200 homes. So between 1,600 and 4,000 homes could be powered by the solar farm.

Because the solar farm would be on a former landfill, it would be subject to extensive permitting through the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, but there is precedent here, Evans said. Solar arrays are being built on an old landfill in South Buffalo, New York. In Houston, a former city dump in the historically Black neighborhood of Sunnyside will become home to one of the largest solar farms in the country.

According to the city’s request for proposals, this project has its roots in the climate plan Dallas adopted in May 2020. The plan, among other things, called for Dallas to invest in and “ensure affordable access to renewable electricity.” A community solar farm, according to the request for proposals, could do just that, providing relatively cheap solar energy to lower-income residents.

It’s a project that attempts to address some of the biggest problems facing Dallas, where our inequality is catastrophic and our climate is heading that way.

But in her June presentation, Evans had almost nothing to say about the wildlife habitat on and surrounding the site. The city’s request for proposals doesn’t mention it at all, naming the Audubon Center only once. (At that meeting, council members had no questions for Evans about the solar farm.)

A portion of the site identified by the city includes a part of the Trinity River Audubon Center, although any solar farm would go on the closed landfill itself, rather than the surrounding wetlands or forest. But that would “cut the habitat in half,” says Sandifer. “The lion’s share of that property, and what really affords the Audubon Center a buffer from the real world — the outside world, the human world — is that closed landfill.” Replacing that buffer with what he says amounts to a “big commercial project” would expose the Audubon Center to the clamor of Loop 12.

It remains unclear exactly what impact construction, and the solar infrastructure itself, would have on the habitat.

A tour of the site scheduled for earlier this month was canceled by the city 45 minutes before it was supposed to start, Sandifer says. Solar operators who had already flown into town to check it out turned up anyway. No one from the city showed. Sandifer did, and spent some time chatting with vendors from companies like Saudi Aramco and Vistra, the parent company of TXU and Luminant.

The vendors had a lot of questions that Sandifer, who is of course familiar with the site, was able to answer. “As I waxed poetic about all the wildlife, just along that stretch — not the Audubon Center, but that hillside they want to turn into a solar farm — a female whitetail deer walked up to our group from that hillside,” Sandifer says. “I posted a photo of that deer watching us talk about how this solar farm would potentially impact wildlife habitat.”

That’s another part of the problem with a potential solar farm, he says. The former dump itself has become a wildlife habitat, reclaimed by nature. “This was all purposely remediated for this wildlife habitat, for a nature center,” he says. “There was no other purpose for this than to revert it back to nature.”

Sandifer recognizes the need for renewable energy and for solar power, especially in a place like Texas, where sunshine is abundant. But he says that, in this case, a solar farm is far from the highest and best use of the land. However well intentioned, this would not be the first time the city has gotten the Great Trinity Forest wrong.

“I think someone was just looking for a random brownfield in a part of town that had a disadvantaged community as part of it, and they were looking for a way to check off a lot of boxes on their climate action plan,” Sandifer says. “I think they said, ‘Oh, here’s a brownfield, let’s go for it.’ I don’t think they realized the purpose of that brownfield, of the Loop 12 and Deepwood landfills, was decided 15 years ago to be that of a wildlife sanctuary.”