A new report from The Commit Partnership shows that the transition to remote learning by area schoolchildren is disproportionately affecting children living in poverty. A remarkable 161,000 households with children – a full 25 percent of all family households in Dallas – do not have access to a broadband subscription service. Around 40 percent of these children live in just 10 ZIP codes.

The research gathered by Commit highlights how internet access is a new benchmark for identifying the causes of cycles of poverty and constricted economic mobility. The lack of a reliable internet connection, the report says, not only inhibits children from learning during the pandemic, but it can also affect post-secondary learning, job training, and job seeking. The cause of the internet divide isn’t access to available broadband service – broadband is available in 99 percent of the region. Rather, residents without internet access cite high costs of service and insufficient credit. These areas also tend to have less access to free public internet access at coffee shops or other hot spots.

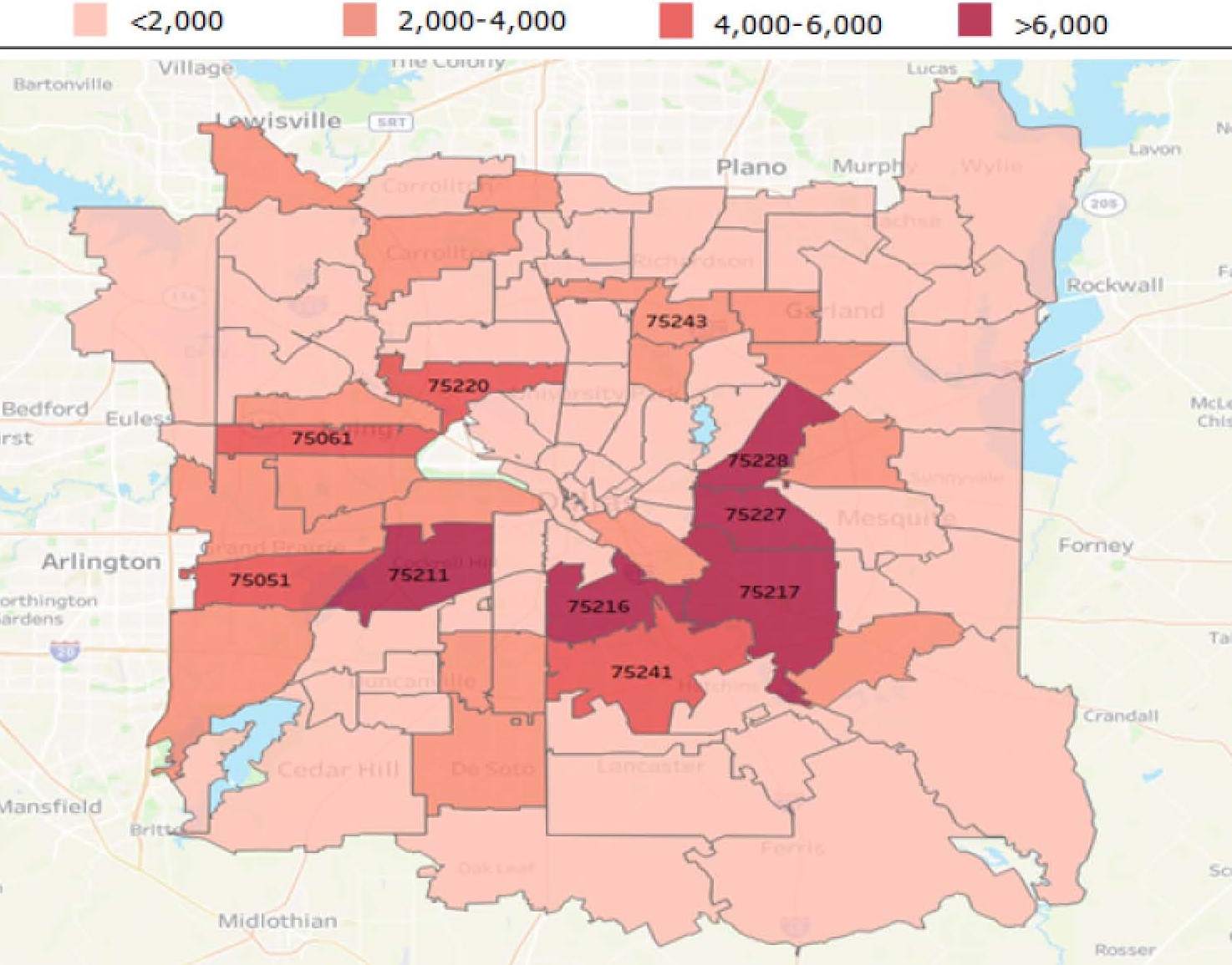

Commit Partnership analyzed data collected by the 2018 U.S. Census American Community Survey and crunched statewide broadband access numbers by zip code. What they found is that a concentration of the houses that do not have access to internet is in the southern sector of Dallas and West Dallas. The communities with the highest numbers of households with children without broadband service include Pleasant Grove, South Oak Cliff, Cedar Crest, Buckner/Ferguson, Grand Prairie, Highland Hills, Bachman Lake, Plymouth Park in Irving, and Vickery Meadows.

The community with the single greatest percentage of children who lack broadband is Highland Hills. The analysis also shows that broadband access declines as poverty increases.

This report confirms what we may have, sadly, assumed, but by putting hard numbers to the situation, it drives home an important point. Internet access is no longer a consumer service, it is a vital mode of social and economic connectivity. Neighborhoods without access to internet are like neighborhoods without access to reliable transportation: they are kept from educational and employment opportunities, which perpetuates poverty. Unfortunately, Commit’s maps show that, in Dallas, the neighborhoods with poor access to transportation are the same ones with the least access to internet. This data suggests we should expect neighborhood inequality to worsen still if this trend continues.

Commit cites a handful of possible solutions, including coordinating with school districts, local governments, and corporations, like AT&T, to come up with solutions for expanding access, with an eye on the November 2020 bond election. They also suggest researching strategies that have been employed around the country, including creating regional community Wi-Fi.

In addition to any specific targeted solutions, the report warrants a reevaluation of the entire way in which internet service is provided in Texas. In recent years, cities around the country have experimented with launching their own public broadband service. Chattanooga, TN, in particular, launched its own municipality-owned internet provider that resulted in much faster connections at a lower cost than private internet services. That upgrade translated into increased tech-sector investment in the city.

However, Chattanooga also faced opposition from the major internet players. When they tried to expand access to their vastly superior internet service to residents in surrounding counties, they were stonewalled by AT&T and its lobbyists, who pushed a law through the state legislature that prohibited municipality-owned internet service providers from competing with private entities. Then, when the Federal Communications Commission attempted to block that measure, the corporations took the city to court and won.

These same corporations have been busy ensuring that more municipal governments are unable to launch their own citizen-owned internet service providers that will out-compete them in the free market.

The Texas Legislature passed a law that prohibits any city in the state from establishing a municipality-owned internet service provider. Given the fact that AT&T’s headquarters is now in Dallas, I imagine any political push to reverse this rule will prove very difficult. But these new numbers from Commit clearly show one of the consequences of this brand of corporate protectionism. Not only does it prohibit cities from launching superior service, it contributes in making the internet unattainable for a quarter of all families in Dallas.

The internet plays a central role in daily life, which has been driven home by the COVID-19 crisis in an unprecedented way. We can no longer treat and regulate internet service as a mere consumer good. Rather, cities should work to expand access to the service as they would any essential civic good, like roads, buses, water, or sewer.