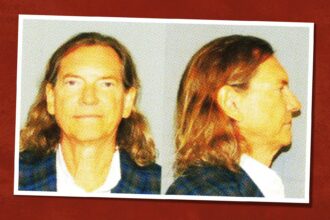

Two years ago,the legendary oilman was divorced, depressed, and discredited.

Look who’s back.

Pride, we are so often reminded, goeth before a fall. T. Boone Pickens Jr. published his autobiography in 1987. The book is modestly titled Boone and starts out: “This is the story of a man who turned a $2,500 investment into America’s largest independent oil company in 30 years and along the way discovered that something is terribly wrong with corporate America. Mesa Petroleum is the company, and I’m the man.”

The book concludes 293 pages later: “Things have never looked better. The MLP [his partnership] had a market capitalization of $2 billion, and during the next six months it would raise another $500 million on transactions already in progress. That was the most financial muscle we had ever enjoyed. Moreover, it was happening when the oil industry was suffering its worst depression ever. It was an endorsement of our management and an indication of tremendous opportunity for those who could predict the future and were willing to bet on their analysis.”

By 1996, Pickens’ once-formidable reputation had slipped to that of an annoying and aging one-note Johnny. He was 67. Corporate America hadn’t really changed much at all and, if anything, was more self-serving than ever. Mesa had run out of money. When Fort Worth financiers Richard and Darla Rainwater stepped in to restructure the company, they booted Pickens out. Mesa’s limited partnership structure, which had been Pickens’ pride and joy in 1987, was replaced with a traditional corporate form. On the personal front, Pickens, who had dedicated Boone to his wife Bea, was in the midst of a messy and highly publicized divorce. The normally irrepressible Pickens was clinically depressed.

I have known Pickens off and on for 25 years, and I have to admit I get a kick out of him. He is the personification of “frequently wrong, but never in doubt.” He is willing to bet it all on his conviction of the moment. Being quite the opposite, I would want to hedge any bet that the sun would come up tomorrow. Pickens is an antidote to the cynical and cautious among us. For many people, though, a little Pickens goes a long way.

When it was a master limited partnership, Mesa paid out far more money to its shareholders than it should have and incurred far too much debt. Pickens embarked on this course because he believed that the price of natural gas—Mesa’s primary asset—would rise inevitably and dramatically to cover any shortfall. Long story short, Mesa got into liquidity trouble before Pickens could be proven right. He was out.

After leaving Mesa, Pickens opened a modest office in Preston Center. Gone were the Falcon 50 corporate jet and the lavish perks he’d enjoyed at Mesa. He had always traded natural gas futures and options for Mesa’s account and his own, on balance successfully. So he formed BP Energy Fund in May 1997 to allow investors (mostly friends) to participate with him in his trading activities.

BP Energy Fund has provided its investors with the wildest roller coaster ride of any investment vehicle I’ve ever heard of and vindicates—belatedly—Pickens’ conviction about natural gas.

The partnership was originally seeded in 1997 with $37 million, $10 million of which was Pickens’ own money. A few investors, not anticipating the vindication of Pickens’ eternal bullishness on natural gas, withdrew $3 million shortly thereafter, leaving $34 million of equity. They had good reason: as gas prices kept falling, to a low of $2 per thousand cubic feet in 1999, Pickens’ fund value kept falling. On New Year’s Day of 2000, BP Capital Energy Fund was down to $4.4 million in equity, which meant the value of the original investors’ holdings had dropped more than 85 percent.

In the summer of 2000, natural gas prices skyrocketed, rising from $2 per thousand cubic feet to $10 per thousand cubic feet. By the start of 2001, BP Capital was worth $244 million. There were no interim capital contributions and no withdrawals. The value of the fund had increased more than 5,000 percent in one year.

Ultimately, Pickens returned $210 million to his partners, retaining the original, or almost original, $34 million. Thus, with a promoted profits interest and management fees, Pickens’ capital account—which had dwindled to $1.2 million—stood at $111 million. Trading gas futures alongside the partnership, Pickens reports that he earned an additional $50 million for himself.

Only in part was this stupendous achievement the result of the approximate quintupling of natural gas prices. Without a messianic belief in the commodity itself, not to mention a die-hard faith in his own judgment and capacity, and the leverage afforded by the futures markets, no such staggering return could have been achieved. A more conventional investor might have done no better than a five-bagger.

The battle cry of beleaguered natural-gas producers in the early 1980s was “Stay alive till ’85.” Any fool could see that anticipated demand would soon outstrip anticipated supply. The inevitable bull market arrived—a mere 15 years later. Most of the obvious demand-exceeds-supply bets I have followed either didn’t work at all or they took so long to work that they were not worth pursuing (gold, silver, oil refining, and aluminum to name a few).

“Why were all of you so off on your natural-gas timing?” I ask Pickens. He replies that, first, there was just more gas in the ground than anybody thought. Second, 3D seismic technology allowed producers to exploit older fields previously thought depleted. And then he just shrugs. A friend of mine expresses amazement at Pickens’ return to the limelight. “I thought they had ground him into dirt and he had blown away five years ago,” he says.

Pickens is back. I decide against asking Pickens whether the 15 years of pain has been worth the gain, thinking he would regard it a stupid question. And whether Pickens’ great year was a function of astute research, bulldog tenacity, or just plain luck is a question I will leave to others. At 73, Pickens is now savoring his best financial year ever and the inevitable notoriety and publicity that flows from it. He feels vindicated.

His bullishness on natural gas seems, for the moment, to have taken a backseat to other interests. In conversation he is more engaging and less egotistical than in his Mesa days. He has remarried. Friends attribute his longer hair to his new wife, 53-year-old Nelda, with whom he says he is the happiest he’s ever been. No shrinking violet herself, Nelda has recorded a CD called Raising Cain. Cain is her maiden name. Admirers say she sounds a little like Patsy Cline. Pickens has given up racquetball and taken up weight lifting. And whether it is the euphoria of a great financial comeback, the new marriage, or the growth hormone therapy he takes and swears by, Pickens looks and feels pretty good.

A friend, Jim Grant, editor of Grant’s Interest Rate Observer, recently asked me how much I would bet that Pickens was now bulletproof—that he could never go broke. I certainly don’t think he ever would, but I wouldn’t bet very much either way. Pickens, as everyone who knows him agrees, is a born plunger and given to levels of enthusiasm that are unimaginable to most of us.

While obviously still bullish on the prices of natural gas and crude oil, Pickens’ current major enthusiasms are his new marriage and a water rights project in the Texas Panhandle. The first enthusiasm (his wife) makes those who know him smile warmly, and the second (water rights) has enraged a great many people.

A friend of mine, Rod Jones, is a young money manager and Nelda’s only child. He is the new stepson of Boone. As an only child, born to Nelda when she was very young, Jones is very close to his mother. And he is a newly converted Boone fan. “Shad, it was unbelievable,” he tells me, marveling at how sometimes the child becomes the parent. “I was out at the ranch in the Panhandle visiting Mom and Boone, and he took me aside and said, ’Rod, I want you to know that I’m damn serious about your mother and want to spend the rest of my life with her. She has the kindest heart and the best spirit of anybody I have ever met. I want to make sure it’s okay with you if I marry her.’ It was exactly the sort of speech a father would love to hear from a prospective son-in-law, and here’s Boone Pickens making the speech at 72. But I told Mom that she doesn’t need to worry about Boone keeping up with her. What she needs to worry about is keeping up with Boone.”

Pickens’ business enthusiasm is mostly focused on his current water rights project. Pickens’ Mesa Vista ranch is in Roberts County, in the Panhandle. He has blocked up the water rights to 150,000 acres, which includes those of Mesa Vista. According to The New York Times, “Mr. Pickens is proposing to pump tens of billions of gallons—to the highest bidder.” Mind bogglingly expensive pipelines would have to be built to transport the water. Pickens believes that water shortages in Texas metropolitan areas like the new suburbs surrounding Dallas and San Antonio are inevitable and that he could make $1 billion capitalizing on the future shortages.

Shad Rower has written for Forbes, Texas Monthly, and Fortune.

Get our weekly recap

Related Articles

Bill Hutchinson Pleads Guilty to Misdemeanor Sex Crime

The Best Japanese Restaurants in Dallas