A specialist in urban rescue takes a look at Dallas.

Edmund Bacon is an archetypal Yankee. Tall and lean, with a finely chiseled profile and an appropriately patrician manner, he might have stepped from the pages of a Marquand novel. Actually he’s spent most of his life in Philadelphia rather than Boston, first as an architect and designer, then as Executive Director of the Philadelphia City Planning Commission from 1949-70. More than any other person, he has been responsible for the renaissance of Philadelphia, one of the most remarkable urban rescue projects in the world. Many of the most innovative ideas there were originally his, while he guided others through the bureaucratic maze with exemplary skill and courage.

The heart of his philosophy of design is the idea of creating harmonious “people places” that evoke strong emotional responses from everyone. ’”The essence of design is the interrelation of mass and space,” he wrote in Design of Cities. “In our culture the preponderant preoccupation is with mass, and to such an extent that many designers are space blind. Awareness of space goes beyond cerebral activity. It engages the full range of senses and feelings, requiring the involvement of the whole self to make a full response to it possible.”

Last month, as the city was debating on the merits of the various proposals for the June bond election, Bacon came to the University of Dallas as one half of this year’s McDermott Lectureship, the other half being Norwegian architect and historian Christian Norberg-Schulz. Bacon conceded that a major appeal of the appointment was the prospect of being able to stroll through the groves of aca-deme discussing design ideas with students and architects and maybe a philosopher or two. He’d no sooner arrived at D/FW, however, than people were asking his opinions on more pressing subjects: What did he think of Town Lake and the new city hall? Was the location for the new art museum really the best one? Should we double-deck Central Expressway? Bacon spoke his mind, to the delight and occasional dismay of his listeners. And between meetings with city officials and excursions to North-Park and Fort Worth, he also took time to field a few questions from us.

Bacon: Before we start jumping all over the place, let me give you this as background. Any progressive American city that I know of is working now to create in its center a new kind of people place, in which people of all racial, ethnic, and economic backgrounds can find a locus for identification – as exemplified, for instance, by Quincy Market in Boston and The Gallery in Philadelphia, which I had a great deal to do with getting started. Accompanying this in all progressive American cities is a network of climate-controlled, all-weather pedestrian footways, which extend outward from the people place on routes independent of vehicular traffic. That means that they may go over or under the existing streets or that the existing streets may be closed to traffic.

A recent Fortune article on these two developments establishes our time as a significant one, because this concept is based on retailing. The direction of the future will be this mixture of public and private institutions – retail, office, recreation, culture, and art.

In terms of the recreational-civic aspect of this, Texas is a leader. I found the Water Gardens in Fort Worth an amazing example of what I’m talking about, though it’s difficult to classify. You can say it’s a park or a market place-agora, or a jungle gym, but none of these really describes it. It’s an extraordinary civic institution, one which is cohesive and brings people of various types together, which I think is crucial.

Dillon: How does this concept apply to the more standard type of civic institution – a museum, let’s say?

Bacon: I was astounded to see that the city of Fort Worth has cooperated with the private developers of the Tandy Center, and is building an underground public library which will open directly into the Tandy Center shopping mall, which lies below street level and which connects a skating rink with office towers, hotels, and a great number of shops. To my mind, this is a precursor of a new trend in American life.

In Seattle, in the Westlake Mall project in the heart of the city, which is being developed by my company, the Mon-dev Development Company of Montreal, the shopping center will have above it the art museum of the city of Seattle. I thought that this would be the first time that a central city pedestrian mall, which in Seattle connects with three department stores by weather-protected bridges, would have been connected with a major civic institution. I am very surprised that Fort Worth is ahead of us. I have a feeling that historically this represents a very important turning point in American perception of art and culture.

The other point I wanted to make about art and culture is based on my Philadelphia experience. In the regeneration of the historical area, which changed, in a very short time, from a slum to a location that attracted high-income suburbanites, there was a ripple effect, a spin-off. Around this new center of vitality grew up a complex, interlocking network of institutions generated by young people with practically no money and with almost no support from any of the more substantial institutions. It consisted of small art galleries, craft shops, studios, restaurants, music halls, experimental theaters, and so on. This came about through the rehabilitation and renovation of old abandoned warehouses, loft buildings, and factories. A concern for the total cultural health of any community must include the major institutions, but if it is to be true culture it must also be worked out so that it encourages and stimulates more experimental and forward-looking efforts as well.

Dillon: There is a historic preservation district in downtown Dallas, the warehouse area. Yet historically, the pattern seems to be that, as soon as there is some kind of official designation, real estate values jump so much that the people who might have moved into the area – the artists and young marrieds – are priced out of it. Some city planners here believe that it’s already too late for a residential phase in the warehouse district.

Bacon: The Philadelphia thing occurred with no institutional support, and I have the feeling that had the city planning commission moved in at the beginning, it would have killed the possibility of its occurring. It was really done by young people, who probably view themselves as largely outside the regular cultural system. But it has grown and strengthened to the point that it has attracted people from the cultural establishment. In Philadelphia we haven’t cut the downtown off from the hinterland by a noose of expressways, so you can always go a little bit farther out if it becomes too economically highbrow near the center. It’s almost organic – the pioneers move in, create a situation, then the less ventur-some and more affluent people follow and the pioneers have to move on.

Dillon: What about the Dallas warehouse district, then, as a stimulus for downtown revitalization?

Bacon: It would be my impression that you have a problem there of the dehu-manization of the street, which in an automobile-oriented society like Dallas can be a severe problem. If you have only wide streets and they are devoted exclusively to the automobile, you don’t have the environment which makes the whole thing flourish. In Society Hill, it was the city itself which put in brick sidewalks and incandescent lights and planted street trees and gardens to create this kind of human ambience. With this done, the formerly despised, moldering warehouses suddenly became minor jewels. People began painting them up and so forth. The same thing is possible here, but it will take a lot of thought and attention to make the environment attractive.

Dillon: One of the concerns I have is that we will get a lot of expensive shops and restaurants, but not the kind of rich residential-cultural mix you describe.

Bacon: Well, I think it would be absolutely marvelous if you got some fancy boutiques and restaurants down there, because of the enormous aridity of downtown Dallas . . . Almost anything that would begin to bring some life and warmth to it would be desirable. The artists and craftsmen and theatrical types will find other locations. Of course, I don’t have to tell you that the danger of the warehouse district suddenly blossoming forth with fancy boutiques and so on is so remote that it’s not a current worry. There is a line of reasoning that so labors over the potential dangers that everyone is paralyzed. You have to plunge ahead. 1 would do everything I could to make the warehouse district a center of creative artists, and I wouldn’t get all hung up on “Maybe it won’t work” or “Maybe later on they’ll be thrown out.” If they are, they may still have made a tremendous contribution to Dallas by calling attention to the potential of the area.

Dillon: It’s hoped, of course, that moving the art museum downtown will also help to generate the kind of spin-off effect you describe.

Bacon: Let me give you another example. The city of Manchester, New Hampshire was considering a bond issue to build a theater and a civic center. They had chosen a location close to the center of the city. I went to look at it and told them it was the wrong location, because it was two blocks removed from the real center. I showed them how they could put it in the right location, where it would be directly connected with a handsome new hotel, so that the hotel and the convention facilities would be completely interlocking and connected by weather-protected passageways. This, in turn, would connect directly with a new retail mall, also glass covered, and with an office tower and Olympic-sized swimming pool. Therefore, they would have used their public funds for the development of public facilities to help achieve the objective they had in mind, revitalizing retail. They accepted this idea of moving two blocks farther in so that this direct connection was physically, economically, and humanistically possible. It’s not just a question of being generally close to the center of the city, but of one or two blocks making all the difference as to whether it actually connects. It’s like a great magnet lifting up a piece of steel. If you put it down it lifts an enormous weight but you put it a certain number of feet away and it won’t lift an ounce.

Now, I talked to the director of the art museum and also city planners about the decision to locate the museum in Dallas. They gave all the conventional reasons why it was not located closer downtown. I’m very accustomed to that kind of reasoning.

Dillon: You’re really saying that art belongs in the marketplace, aren’t you? Some people think it ought to be set apart.

Bacon: The idea that retail is bad, and not for the nice people who go to art museums, is false. The culture of the past has grown out of retail activities. In the Athenian agora, where people came to buy food, there were political discussions and the beginnings of the theater, which produced the great Greek culture. The same was true of the Roman Forum, the medieval market place, and the Baroque piazza. Retail is really the foundation of human interaction which leads on into culture and creative political activity. If you allow retail to die in the center of the city you’re doing your city a profound disservice.

Dillon: In the initial discussion of an arts district several years ago, there was talk of scattering the various facilities around the central business core, spreading the wealth, so to speak. What are your thoughts about that kind of arrangement?

Bacon: The current experience of American cities has proved that any public expenditure in the vicinity of downtown should be directed to creating the most concentrated assemblage of activities that you can possibly get, and that it should be just as closely connected to the business and retail core as it is physically suitable to do, even at the cost of higher land and infra-structure costs. In the long run it’s a much more economical investment because it actually helps to keep the downtown alive. I also think that a judicious dispersing of magnets through the central area could have the effect of pulling people through the retail and business core. Could. I said could.

In looking at Dallas, it seems to me that the flow of people from the large and enormously expensive convention center, built by public funds, to their hotels and interests in the center of Dallas would be of crucial importance. And it seems to me surprising that public funds have been expended on the city hall, the city hall plaza, and on the library, and apparently no thought has been given to linking them together in a continuous pedestrian way where a most extraordinary opportunity was offered to do that. I would even raise the question as to whether it’s too late to give some thought to it.

Dillon: In Design of Cities, you talk about the importance of “shafts of space” moving outward from a central point and pulling a city together, as in the Vatican. Could the new city hall function in that way, be our St. Peter’s on the Trinity?

Bacon: Did it ever occur to you that the tremendous volume of space in the city hall itself, the interior space which now goes up six floors and is virtually deserted, could become a city street? You could build a skywalk from the convention center over Akard in the west end of city hall, right through the center. You could then build a protected arcade across the east end of the plaza that went into the upper level of the new library. And if the library were designed with a similar kind of corridor or people space through it, you could go directly to the old Trail-ways bus terminal and pretty soon, you’d be into the second floor of Neiman-Mar-cus. So the “golden flow” of people from the convention center, which I understand produces some 70 percent of the money spent in the downtown, could proceed through one of the architectural wonders of the age, which provides a splendid view of the city and Reunion, into the downtown. Dallas would have one of the most spectacular processional ways of any city. And of course most of it is already built.

Actually, if you did this you could probably build a new building on the plaza. It’s so enormous, too big really, if I may say so. In a sense, Pei seems to have ignored one half. He drew a diagonal through it, as though he didn’t really want the other half. You might build a historical museum, for example. By that you would utilize the buildings you’ve already built and also link things together.

Dillon: It seems to me there’s still a great deal of piecemeal development going on. We ’re putting up buildings that often are very interesting in themselves but that don’t relate very well to their surroundings or to other buildings.

Bacon: I recommend that you quote yourself on that point. I have this problem of how to speak my convictions and still remain a polite guest.

But dammit, I’m talking about a gut economic issue, not some eccentric art project. It’s stupid for a city that has this “golden flow” of people from the convention center to bypass the retail facilities. The one practical principle of retailing is to develop routes for people, so that they’re exposed to the retail outlets and know the facilities that are available. What is there in Dallas that attracts people from all over the world? Neiman-Marcus. You could so easily incorporate that into the route.

Dillon: You were saying earlier in the week that Dallas has not yet learned how to use its landscape in its designs. Could you expand on that point?

Bacon: The tradition of Texas urban development, as exemplified in the courthouse towns – which I think are some of the most beautiful artifacts of man on the face of the earth – is that when people moved across the vast anonymous spaces and decided finally they were home, they moved in very close together, developing very close-knit, urbane designs. In fact, they developed some of the most highly focused towns that have ever been built, with the inner square, then right in the middle of the square the courthouse dome, which established a point in space. The streets around the square were close together, with all the shops looking inward so that you hardly ever saw the country beyond.

Historically, downtown Dallas was a highly urbane place. The buildings were all close together; the hotels were close to the stores and offices. It was very tight. It was only the invasion of the automo-bile, and a misunderstanding of the primacy of the automobile, that tore this cohesive fabric apart into a series of parking lots. Suddenly institutions found themselves isolated in great deserts of open space devoted to the automobile. So that my view of the response to the vast spaces of Texas is that in the cities, when you’re finally home, you create a warmth and a closeness by intimate spaces which give the contrast to the great outer spaces.

Dillon: What about sky? There’s just so much of it here.

Bacon: Sky is certainly important, but so are sun and heat and wind. So is human comfort, especially here in Dallas. There’s an irony about this. Although people in Dallas and Texas pride themselves on a tradition of great open space, they usually observe it from inside their air-conditioned sedans. It’s possible to delude yourself here on the closeness to nature argument. But when you have great expanses of concrete to the extent you do in city hall plaza, with so little relief from sun and wind, it really raises the question of whether that particular pattern is as appropriate for this kind of climate as it might be in more temperate areas.

One has to think very thoroughly through the bodily response to where you are. It’s possible, as was shown in The Gallery in Philadelphia, to build structures in which you are very aware of the sky, in which there are glass roofs and inside-outside connectors, but in which you recognize the human desire for comfort, which is very highly developed in Dallas, by providing spaces that are climate-controlled. As you know, Dallas has started a system of underground connectors. They’re certainly useful and some of them are quite good, but they’re much less attractive the way they’re done here than, let’s say, in Minneapolis, where there are skywalks and so on.

Dillon: As you and everyone else has observed, almost nobody lives downtown right now. Essentially it’s a 9 to 5 environment. Fox and Jacobs have proposed to develop middle-income housing within a mile or two of the central core. Is this kind of partnership between the city and a private developer, at least as far as land acquisition is concerned, an effective way to attract people downtown?

Bacon: Well, you can kid yourself on this subject, because in Dallas many people are moving back downtown of their own volition. That’s the most encouraging sort of situation you can have. So in a certain sense I would say that Fox and the city are following a trend which was already established by individual initiative. I’m very glad to see that, because the real energy of the downtown revival of older cities has come from that kind of initiative, although such a phenomenon as Society Hill in Philadelphia, which was an organized government effort, can act as a stimulus.

The return of people to downtown living is inevitable. It’s occurring all over the country to various degrees, influenced to some extent by how progressive and forward-looking the citizens of those cities are. It’s happening here to a significant degree, and it’s important to recognize that this phenomenon does exist. It’s possible to wreck it by an insensitive, overly organized government-developer combination. I don’t know the particulars of the Fox proposal, but I understand that he is sensitive to these issues and values.

Dillon: What are the dangers in this kind of government-developer venture?

Bacon: There.is always the temptation on the part of the developer to rip things to pieces with the idea that he is going to create a new environment. There is also the notion that you have to have a large environment to protect you from bad influences. If you have the chance, go to St. Louis to see what they did in the Mill Creek area. They had an opportunity to create something wonderful and they split the place apart and created a non-place through uncoordinated and insensitive private development. I hope very much that Dallas will not do that.

An interesting thing emerged in Philadelphia. The typical suburban home-builder, when he goes down to the center of Philadelphia and builds the same type of houses there, with the purple bathroom fixtures, the pink and purple carpets, and the iron sconces on the walls, creates an atmosphere that is antipathetic to the families living there, the kinds of cultural backgrounds they have. It’s really a whole new ball game, and I hope that Fox is aware of this.

Therefore, the two crucial things are, numberone, that you save every existing building that you possibly can, that you respect the character of the neighborhood, preserve the institutions, the trees, and the texturing of the buildings. Second, you must be very sensitive to the kinds of cultural forces at play, the kinds of interests that the younger professional families who will be attracted back there expect and want, which are quite different from the sorts of things you find in the typical suburb. The point is that many of the people attracted back downtown will be young families with children. A lot of people adopt the stereotype of the empty nester, as though all you had were single and old people. This has not proved to be the case. Many young families seek for their children the richness that only a central city can provide, the mixture of races and income groups and the wide range of cultural activities. Not just artificial kinds of expression, like television and hi-fi, but live theater, live music.

Dillon: A city also needs a cohesive image. Does Dallas have one?

Bacon: Having just come from FortWorth, I have this powerful image ofFort Worth with its Main Street and themagnificent courthouse at the end. I thinkthat’s one of the great urban vistas in theUnited States, the world possibly. Andit’s such a simple thing really. I search inmy mind in vain for something comparable in Dallas. I do think that the proliferation of expressways is not conducive tocreating a cohesive image. I must saythat one of the most vivid images of downtown Dallas is the locked gate. I arrivedat Thanks-Giving Square at five minutesafter five and couldn’t get in. I was excluded from participating in the pleasuresof a place I very much wanted to see.That’s a telling image.

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Local News

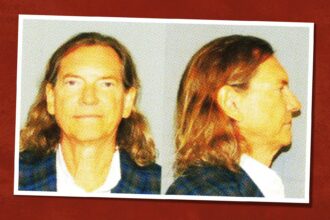

Bill Hutchinson Pleads Guilty to Misdemeanor Sex Crime

The Dallas real estate fun-guy will serve time under home confinement and have to register as a sex offender.

By Tim Rogers

Restaurants & Bars

The Best Japanese Restaurants in Dallas

The quality and availability of Japanese cuisine in Dallas-Fort Worth has come a long way since the 1990s.

By Nataly Keomoungkhoun and Brian Reinhart

Home & Garden

One Editor’s Musings on Love and Letting Go (Of Stuff, That Is)

Memories are fickle. Stuff is forever. Space is limited.

By Jessica Otte