During the Second World War the loudest complaint from the British Army in Scotland about the American soldiers was that “They are overfed, overpaid, oversexed and over here.”

Now the Scots have another, perhaps profounder complaint about Americans: that we’re drinking Scotland dry. The USA buys and consumes 50% of the total Scotch whisky production, leaving 15% for the British market and the remaining 35% for the rest of the world.

The easiest tax any government can levy is on alcohol, but in Scotland how far can a government go? It’s truly a question of life and death: if the taxes get too high, will a Scot stop paying or stop drinking? A truly spine-chilling dilemma that makes my sympathetic heart shudder.

There are basically two types of Scotch whisky:

Lowlands grain whisky, made south of a line drawn from Dundee to Greenock, is mostly distilled from a mash consisting of assorted grains like maize, rye, even oats, with only a small proportion of malted barley. Distillation is carried out in a continuous-process patent still and the resulting product is mild, rather pedestrian in taste, and used strictly for blending. As far as I could find, only one of the grain whiskies is bottled under its own name, and you can have it – I’ll take white lightning from the Piney Woods of East Texas any time.

Highland whiskies are made from the mash of 100% malted barley and distilled in slow, old-fashioned pot-stills, giving them a wide spectrum of distinctive characters and styles, full body and a pungent, smoky smell.

The grain whiskies date only from the invention of the patent still in 1830, but the single malts date back to ancient Gaelic days. The blending of the two into hundreds of quite distinctive blends began about 1860. It made Scotch whisky a household word all over the globe and the first choice of sophisticated drinkers. Until the invention of the patent still Scotch whisky was not popular even in England, where the fashionable spirit at that time was brandy.

Out of roughly 90 Highland distilleries, only about 40 bottle part of their production under their own labels. All the others sell their whole output to the blenders. But there are passionate aficionados of that 1% of unblended single malt Highland Scotch whiskies, so let’s concentrate on them.

Now 99% of all Scotch whisky consumed all over the world is blended. The cheapest blends contain as much as 70% grain whiskies, while the most expensive contain as little as 25%.

The Highland Scotches come from six different areas of Scotland: the Moray Firth, Campbelltown, and the islands of Skye, Islay, Jura and Orkneys. All of the whiskies in a given area are sort of kissing cousins, but differ tremendously from those produced in other areas. Each distillery in the same area produces a distinctive, individual flavor because the most important factor of the taste is the source and quality of the water. Every distillery has its own spring and those with water running over granite sub-soil under a surface of peat are considered superior. The local peat used as the source of heat gives the whisky its own smoky, mysterious flavor.

There is no way, anywhere in the world, to duplicate all of the factors which make Scotch whisky unique. Many have tried, but no one has even come close. Not even the Japanese.

The actual process of making single malt Scotch whisky is slow and laborious. It is started by placing barley in tanks and pouring water over it for four to five days, until it is completely moist. In the next step the barley is spread evenly over the floor in a separate malt barn for germination. The sprouting is controlled by maintaining even temperature in the building and turning the grains over with large wooden shovels, a brutal, back-breaking labor. The germination is stopped when all of the starch has turned into sugar – usually about eight days. The malt is now moved again into another building equipped with a perforated wire floor below which a slow peat fire is burning. The smoky heat dries the malt and imparts to it the desired peaty flavor. In the next step the malt is ground into a very coarse mash, mixed with hot water, which dissolves all of the sugar. Finally the liquid – by now called the “wort” – is strained. The solids are used for cattle feed, and the wort is pumped into fermenting vats, where the added yeasts kick off the fermentation. In three days all of the sugar converts into alcohol. The liquid is now called the “wash” and is ready for distillation. In the next step, the wash is distilled twice through two separate, different stills. The resulting pure, colorless malt whisky is aged in barrels for at least three years. But it is at its very best after eight to 15 years.

The finest habitat for the whisky’s long slumber is a used sherry cask. The wine-stained wood colors it a beautiful rich amber and the slow oxidation through the wood mellows it to a silky smooth texture. Alas, nowadays there are few sherry casks and they are too expensive, so normal aging is done in regular oak barrels. The exact shade of color is controlled by a slight addition of caramel. The results are just as good.

Single malts are for Scotch drinkers what Hennessy “Extra” is for brandy lovers. Naturally and deservedly these great whiskies are more expensive than the blends and not as readily available.

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Local News

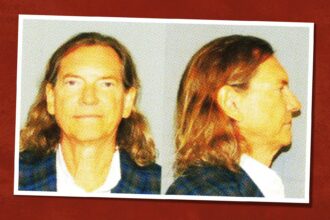

Bill Hutchinson Pleads Guilty to Misdemeanor Sex Crime

The Dallas real estate fun-guy will serve time under home confinement and have to register as a sex offender.

By Tim Rogers

Restaurants & Bars

The Best Japanese Restaurants in Dallas

The quality and availability of Japanese cuisine in Dallas-Fort Worth has come a long way since the 1990s.

By Nataly Keomoungkhoun and Brian Reinhart

Home & Garden

One Editor’s Musings on Love and Letting Go (Of Stuff, That Is)

Memories are fickle. Stuff is forever. Space is limited.

By Jessica Otte