NOT TOO many years ago in Dallas County, “Republican candidate” meant the same thing as “sacrificial lamb.”

Republicans had little party machinery and few enticements for candidates or voters. County Judge Lew Sterrett kept a firm hand on local patronage, rewarding Democratic Party loyalists with every possible plum. An unbroken string of Democratic governors ensured that the courthouse would be dominated by Democratic judges by naming only the party faithful to new or vacant benches.

This Democratic dream machine took a beating with the 1974 election of Republican John Whittington as county judge, then fell apart four years later when Dal-lasite Bill Clements became the first Republican governor of Texas in more than a century. The campaign apparatus that garnered 59 percent of the Dallas County vote for Clements made its expertise available to other GOP candidates. Republican lawyers started snaring governor-appointed judgeships. Momentum-just as mysterious in politics as in football -had shifted. The Republicans were on a roll. Democrats grew defensive, scared and scarce.

Then came the 1980 election. While Ronald Reagan was sweeping Dallas County, Republican judicial candidates were achieving unprecedented success. Only two Democratic judicial candidates who drew Republican opponents won their races. Rarely has there been such a drastic turnabout of political fortunes.

Traumatized by these sudden reversals, the Democrats seemed dazed and ineffective-too enfeebled to fight back.

When the pendulum swings this dramatically, the reverberations can be long-lasting. Young people with political ambitions but no partisan loyalties tend to affiliate with the party most likely to be a winner. During the past few years, the winner’s image in Dallas has belonged to the Republican Party.

As 1982 began, Dallas Democrats looked like victims of a political plague. Convinced they could not withstand Republican challengers, Democratic judges were switching parties. The Democrats were broke, disorganized and had no visible program or leadership. Enter Bob Greenberg.

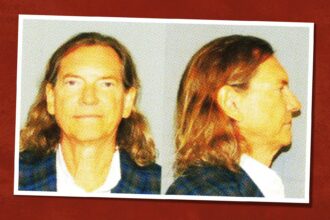

An East Texas native and 20-year Dallas resident, Greenberg, 45, has earned a reputation as a tough, effective trial lawyer. Until this year, he had never run for office. Although he is identified with the moderate-conservative wing of the party, Greenberg’s campaign for county party chairman was based not on ideology, but on that ephemeral political quality, “leadership.”

The outgoing chairman, David Car-lock, had had neither the time nor the energy to rally the party. Greenberg’s hyperactive campaigning seemed to promise deliverance from the party’s lethargy. Popping up at rallies in his chauffeur-driven Cadillac (“bringing some class to the job,” he said), Greenberg was like an irresistible force, particularly when there were few people inclined to resist, anyway.

Even if you don’t like Greenberg, you can’t ignore him. He fires salvo after salvo at the opposition. He scores some hits, some misses, but he keeps firing as he tries to correct the problems caused by political invisibility. Until he took over, he says, “there wasn’t a spokesman for the party who was getting through to the media, so Democrats weren’t aware that there was a Democratic Party somewhere.”

Greenberg disagrees with those who say that there simply aren’t that many Democrats in Dallas anymore. “There really isn’t any problem with finding people who are Democrats,” he says. They’re everywhere. At least, I’ve found them everywhere. The problem was that there wasn’t any leadership for them to tie to. I think that problem’s pretty much been solved.”

Some of Greenberg’s critics say that visibility and leadership are not necessarily the same thing. They say, for example, that Greenberg’s loud and persistent attacks on County Elections Administrator Conny Drake have been an embarrassment to the party.

But Greenberg’s high profile also is winning him some friends. Congressional candidate John Bryant says the new chairman “so far is doing a real fine job, with lots of activity and lots of speaking out.” Former County Chairman Ron Kessler agrees that Greenberg “is visible and sparking some enthusiasm. At least you know we’ve got a party organization.”

One of Greenberg’s most successful ploys was his September debate with his Republican counterpart, Fred Meyer. Even though the level of discourse was not particularly elevated, Greenberg proved he could at least hold his own with the highly respected Meyer. The debate drew a large, enthusiastic crowd and substantial news coverage. With so much attention, Greenberg was in his glory.

Beyond all the sound and fury of day-to-day hell-raising, there remain serious doubts about what the local Democratic Party really stands for and who its true constituents are.

Bryant sees “less ideological friction” in the party and says “people agree with each other more.” The reason, according to Bryant, is that “the Republicans who were in the Democratic Party have left.” Bryant is among those who say good riddance to John Connally and others they consider never to have been “good” Democrats. The purged party undoubtedly is a more liberal party.

Kessler, on the other hand, advocates a “non-ideological kind of party that can reach across the spectrum” of political activists. “The worst thing we could do,” Kessler says, “is do what the Republicans are trying: become a party of only one ideology.”

Greenberg echoes this when he accuses the Dallas County Republican Party of being “controlled by a radical element.” Both Greenberg and Kessler think the time is right to woo moderates who as yet have no strong ties to either party. Kessler is particularly interested in the “new Texans” who are shopping for an attractive political home. Included among these, he says, “are moderate Republicans who might be lured away from the far-right dominance of their party.”

This search for “new blood,” particularly among the young professionals in town, is an area of keen partisan competition. Tom Dunning, a veteran Democratic campaigner and former member of the Dallas Park Board, helped organize the “El Tax-co Group” (named after its meeting place at a downtown restaurant). This informal forum, he says, “will make sure some of the young people in town meet some of the outstanding Democrats. It’s too easy to become convinced that everyone is a Republican.”

Dunning has been joined by Kessler, former City Councilman Bill Blackburn, State Senate candidate Chet Edwards, homeowners’ association leader Tom Tim-mons and others in occasional discussions of issues and politics. The group has talked about putting together a Democratic “summit meeting” in Dallas to come up with an economic plan as the Democratic response to Reaganomics.

Harden Wiedemann is among the young politicos who have welcomed the advent of the El Taxco Group. “It’s tough,” he says, “when you’re a white-collar Democrat in Dallas. When you start talking politics, everyone assumes you’re a Republican. When you say you’re a Democrat, people look at you like you’ve got gangrene.”

The Dallas Democratic Forum is another project oriented to young professionals. The forum sponsors debates, speeches by national party leaders and social events. It is part of the continuing effort to keep the party visible.

Even with these new activists, the Democrats remain in serious trouble. This year, for example, Democrats were able to field candidates for fewer than half the local judicial races. No party can survive if it gives away elective offices by default.

Another matter Democrats must resolve is fund raising. Not even Greenberg can find a bright side to the party’s financial picture. Asked about the money situation, his only response is, “terrible.”

According to Kessler, this is the true Achilles heel of the party today. “I’m appalled,” he says, “at how easy it is for Republicans to raise money here. We’re not going to be competitive until we can raise money at the $10 and $25 level.”

The national Democratic Party faces the same problem. Not only have the Republicans raised millions of dollars more than the Democrats, but they can also claim a smaller average gift. That means Republicans are winning the battle to build the broadest financial base.

If Greenberg can devote the same energy to fund raising that he has to publicity, Dallas Democrats might receive the financial transfusion they so desperately need. A starting point would be to identify the most consistent Democratic voters (by studying primary voting rolls) and solicit them with a sophisticated direct-mail ap-peal. This in itself is costly, but Greenberg should be able to raise the seed money he needs. As more money becomes available, the party will be able to do more for its candidates. When Dallas Democrats reach the point where they can publicize and work for their entire slate of candidates, the party will seem much more attractive to potential office seekers.

At the moment, major Democratic candidates know they are on their own. Bryant says it is “just me and my organization,” not the party, that will make or break his Congressional candidacy. Until it can provide money and comprehensive campaign expertise, the party will face a “Who needs it?” attitude from many of its own candidates.

Greenberg knows this and is trying to respond with imagination as a substitute for dollars. One of his most interesting maneuvers is the formation of a Neighborhood Coordinating Council in an effort to share the clout of some of Dallas’ increasingly powerful neighborhood associations. In many parts of Dallas, these groups have replaced political parties as the principal vehicles for citizen activism. Greenberg’s “if you can’t beat ’em, join ’em” approach makes sense. If the neighborhood groups accept Greenberg’s offer to serve as liaison with Democratic officeholders, it will plug Democrats into machinery that could revitalize their own grass-roots operations.

One of the common topics of conversation among Dallas’ political junkies is whether or not Dallas is now truly a “Republican county.” Greenberg vociferously argues that aside from judges, Democrats still control most of the elective positions in the county. Fred Meyer, on the other hand, points to the defections of Democratic judges, the ample supply of Republican candidates and the 1980 presidential results in the county as proof that Dallas has become Republican territory.

In spite of the passion each man puts into his argument, neither is correct. Dallas County has become a true two-party community. From now on, one party might hold the upper hand in a given election year, but it is foolish to think that any permanent dominance will be established. For one thing, voters today are much more likely to cross party lines any number of times on a single election day. As political parties have become less significant, one-party control has become more elusive.

The Democrats, however, will have to work hard for a comeback. They still have a long way to go before they can claim the lasting loyalties of more than a relatively small bloc of voters. Ronald Reagan might make a convenient whipping boy for a while, but voters want to see some positive, alternative programs, not merely criticism of the president.

This, too, is a national party problem. Is the Democratic Party the party of Kennedy, Mondale, Glenn, Strauss, Hart, some of the above, none of the above? Greenberg says, “differences with the national party are narrowing because I think the national party is moving more towards the middle and the local party is moving more towards the middle.” Maybe so. But what is in “the middle”?

This search for identity continues to hinder Democratic efforts to expand the party’s base. If Reagan’s political prospects improve so that he no longer is such an attractive target, the Democrats might find themselves hard pressed to offer a rationale for voter support.

It’s fine for Greenberg, Kessler and others to talk about a broad-based party, but that base still requires coherent definition. To the average voter, the Democratic Party still seems little more than an amorphous mass.

The competition between parties will be for money and candidates as well as for votes. If Democrats do well this year, finding candidates and funds for 1984 should be easier.

The Democratic Party is by no means dead. Confusion might seem alarmingly rampant within the party organization, but that is endemic to Democratic operations. Bob Greenberg came along at the right time. He and his party won’t win every contest, but they won’t let the Republicans forget they’re around, either.

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Local News

Bill Hutchinson Pleads Guilty to Misdemeanor Sex Crime

The Dallas real estate fun-guy will serve time under home confinement and have to register as a sex offender.

By Tim Rogers

Restaurants & Bars

The Best Japanese Restaurants in Dallas

The quality and availability of Japanese cuisine in Dallas-Fort Worth has come a long way since the 1990s.

By Nataly Keomoungkhoun and Brian Reinhart

Home & Garden

One Editor’s Musings on Love and Letting Go (Of Stuff, That Is)

Memories are fickle. Stuff is forever. Space is limited.

By Jessica Otte