The heart monitor in the third-floor hospital room sounds like a record skipping, its beep-beep-beeps filling the otherwise quiet intensive care unit. The brain-dead patient it is connected to has been suspended in time for hours, trapped in a loop that will only end once the transplant surgeons arrive.

Recently, a pair of physicians disconnected the patient’s ventilator to see if the brain would order the lungs to pull in air. It didn’t. They performed a test to see if blood was flowing to the brain. It wasn’t.

The incident that put this person here—patient privacy laws prevent revealing what happened, where it happened, or anything about whom it happened to—didn’t damage any of the other organs. With that ventilator, the heart beats as if the patient is oxygenating independently. The lungs fill with air then depress. The kidneys and the liver and the pancreas—those are still good, too. But the person everyone knows is gone; those tests confirmed it. And so the family decided to donate their loved one’s organs so someone else can live.

Samantha Rutledge and Anna Cervantes, coordinators with Southwest Transplant Alliance, were soon in a shaky, eight-passenger Cessna, on the way to help surgeons remove the organs. Southwest Transplant Alliance is one of 58 organ procurement organizations (or OPOs) in the United States. Think of these as middlemen in an organ transplant. They link the hospitals, charter flights for the surgeons, arrange transportation to and from the runways, and aid in the procurement. They’re the glue holding the whole thing together.

I deplane with Rutledge and Cervantes and climb into an ambulance headed to the hospital. I am following the heart, which will be transplanted into a patient at Baylor University Medical Center, back in Dallas, later in the evening. In just a few short years, Baylor’s heart transplant program has grown to be one of the busiest in the country. The volume dropped off last year, but the center still performed enough procedures to fall in the top five.

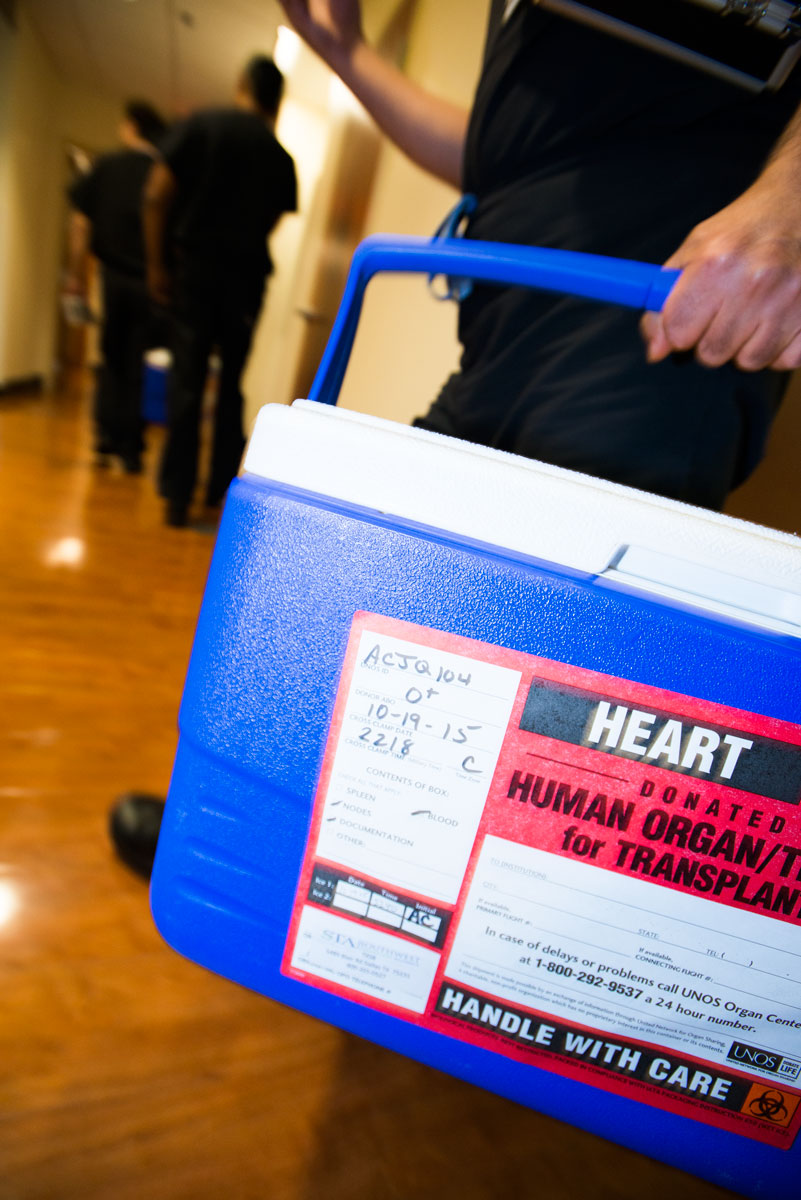

The ambulance pulls up to the hospital’s emergency room. Rutledge unbuckles herself and cranes her slim frame to open the back door. Cervantes reaches for a pair of royal-blue coolers near our feet. “Once you work with these,” she says, hoisting one onto the bench, “you’ll never buy Coleman ever again.” Part of her job is to get these iceboxes in the hospital, as well as the sterilized solution that will freeze from slush into ice and keep the organs preserved for the few hours that they’re outside a human body.

A car wreck occurred while we were in the air, and the victims were being treated in the operating room needed for the procedure. So we wait. The family lingers on their goodbyes in the ICU, a half-dozen men and women clutching each other and sobbing bedside. Down in the basement, the surgeons fill out paperwork and idly watch Monday Night Football. They swap stories, like the one about the Puerto Rican transplant surgeons who nearly came to blows in an operating room because of a disagreement about where on the patient’s body they would cut into.

Once the OR is prepped and the patient is wheeled in, the group shares in a moment of silence after a surgical assistant reads a brief paean:

To all those who are touched by what we do here today, let us not forget that it began with the gift of this one person. May this last act of charity be a testimony to his legacy.

Outside the frigid OR before the procedure began, I told Dr. Gary Schwartz, a thoracic surgeon at Baylor, that it’s surreal transitioning from a family in anguish to a group of surgeons who appear relaxed and focused.

“It’s like what I always tell medical students: don’t lose the tree from the forest,” he says. “At the end of the day, yeah, the patient’s brain-dead. But that heart is still beating. And we’re gonna stop that. You can’t take that lightly.”

One of the surgeons saws through the breastbone with an oscillating saw, emitting a foul odor into the room. Baylor procurement surgeon Raj Malyala cuts in near the patient’s trachea, allowing him to snip behind the aorta, avoiding the risk of nicking the tube that’s carrying blood to the rest of the body. Malyala grips the heart in his hand, twists it to the left and to the right and declares it healthy for transplant.

Two hours later, Malyala double-clamps the aorta, the blood flow stops, and the heart monitor, finally, hums a steady tone.

•••

According to the American Heart Association, there are 5.1 million people in the United States suffering from some form of heart failure. There are 825,000 new cases annually. As many as 510,000 Americans are believed to have progressed to the most severe stage of heart failure, which would be extreme enough to be considered for a transplant. At this stage, the heart is so weak that it cannot pump enough blood into the aorta to get to the rest of the body.

If a patient is eligible for transplant, he is placed on a federal waiting list in order of severity. The Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network defines those codes: status 1A, followed by 1B, 2, and inactive. The patient is then ranked by the amount of time he has spent on the list. Status 2 patients do not require intravenous drugs and are typically allowed to be at home while they wait. Inactive patients are typically ruled as such because of an infection or other complication, but still accumulate time spent on the list.

[img-credit align=”alignleft” id=” 39529″ width=”801″]

[/img-credit]

[/img-credit]Some patients receive a left ventricular assist device, or an LVAD, a mechanical pump that carries blood out of the heart from a tube and distributes it to the rest of the body. LVADs can be used as a bridge to a transplant, holding a patient over until a heart becomes available. And once the patient has an LVAD, they can immediately be listed as status 1A should any complications arise, such as clotting, bleeding, or pump malfunctions.

Every Thursday at 7 am, members of the transplant department meet at Baylor’s Charles A. Sammons Cancer Center, a curved 10-story building at the southern tip of the Baylor campus. They discuss whether the patients they’ve seen this week are in need of a transplant or an artificial heart or a different course of care altogether. If eligible, they designate their status code and get them added to the list.

Attending this meeting are the obvious stakeholders, the surgeons and cardiologists and immunologists. But there are also representatives from the finance department, social workers, and infectious disease experts. The best—and, really, only—way to develop a course of treatment for someone is to understand everything about them, from their habits to their financial obligations to their acuity.

On an October Thursday, two dozen of these experts sit in beige leather chairs around the table. Another 15 or so line the walls. Sitting at the table’s head is Dr. Shelley Hall, the medical director and chief of transplant cardiology and mechanical circulatory support. Hall, 52, was the first transplant trainee at Baylor University Medical Center. She’s been here for 18 years and has served as chief since 2013. She’s been medical director for the past 13 years. Today, she’s wearing a white lab coat over purple scrubs. Also: Saucony tennis shoes with purple laces, purple fingernails, and purple-rimmed glasses. She wears different-colored scrubs each day; the standard blues and greens got old quick.

The surgeons wear all black. Dr. Gonzalo Gonzalez-Stawinski sits halfway down the table in his medical scrubs, a thicket of chest hair creeping out of his V-neck. Baylor’s chief of heart transplantation looks younger than his 48 years, his age tipped off only by his thinning hair and graying stubble. Under their leadership, no other American heart transplant program has grown so much so quickly.

In 2014, its surgeons transplanted more hearts—102—than all other programs in the country except for Los Angeles’ Cedars-Sinai Medical Center (they did 120). Those two were the only centers in America to log more than 60, and Baylor’s number is more than five times as many as its program did in 2009 (20). Last year, Baylor performed 60 heart transplants. That number looks small compared to its 2014 volume, but it’s the most in Texas and still the fifth-most in the United States. There are two reasons for the decline, the chiefs explain. One, more patients received LVADs in 2015 compared to 2014 (50 to 29), meaning fewer patients were qualifying for transplant. Conversely, Baylor wasn’t able to keep enough people on the waiting list to have a steady flow of transplant patients as it did in 2014. It is a victim of its own success.

“Our problem has nothing to do with donors. Our problem has to do with recipients: we don’t have them,” Gonzalez says. “We have a joke around here that we’ve cured heart failure.”

Gonzo, as he’s called throughout the halls of Baylor’s flagship hospital, joined the staff in 2012. During the meeting, when he isn’t speaking, he fidgets. He chews on his pen, picks at his nails, stretches, eyeballs his phone. He absorbs the information until he can take in no more, then unloads his opinions. Today, there is a patient that is in too poor health for transplant. There is another who has been listed at another center for four years. This one wins a 1B designation today.

Baylor gave me access to the transplant program that it has granted no other reporter. To ensure that this story did not violate any federal patient privacy laws or any of Baylor’s policies governing the privacy of its doctors, D Magazine agreed to give Baylor’s lawyers prepublication review of this story. By agreement, Baylor could make changes only to material that concerned privacy or policy matters. Baylor made no changes.

While I attended these weekly assessment meetings, I couldn’t identify the patients without their permission. The final patient discussed during this week’s transplant team meeting—a 66-year-old Mississippian named Charlie Robbins—does give his permission. About 10 years ago, Robbins’ daughter died in a car accident. She donated her organs. That’s why he agrees to participate, so that he can raise awareness about organ donation. When he was 63, he had an LVAD put in at New Orleans’ Ochsner Medical Center. He had no history of heart disease in his family, and doctors haven’t figured out what caused his heart to fail. He’s been on the transplant list since 2013 and decided to double-list at Baylor to see if he’d have better luck getting a heart.

Hall calls up Robbins’ information on the projector. Gonzo is quiet, looking intently at his phone. Robbins is moving here from Mississippi on Monday and he’s asymptomatic, but a blood test shows that there may be a blood clot lodged in a vessel, a condition called a thrombus. If so, he qualifies for 1A status. Gonzo is still focused on his phone.

“We need to evaluate him further with a ramp study and a visit,” Hall says, referring to a test that increases the mechanical heart’s pump speed to test whether there’s any blockage. “The sooner he gets here, the better.”

Gonzo pushes his chair out and stands up, putting his phone to his ear as he rushes out of the room. Hall continues to discuss Robbins with her staff, going over bloodwork, analyzing his levels to see whether his heart tissue is breaking down.

Gonzo reenters and sticks his thumb up. The room applauds as Hall spins around in her seat, slapping palms with her colleagues.

Then Gonzo confirms what everyone already knows: “Guys, we got a heart!”

•••

Raj Malyala, Baylor’s lead procurement surgeon, calls for scissors, which he’ll use to cut out the heart. The heart pumps with a furious rhythm that makes it appear as if it is trying to escape its owner’s chest. He directs 30,000 units of a drug called Heparin to be administered to thin the blood and prevent clotting as it’s flushed out of the body through plastic tubes that look ready to burst from the volume. Finally, he cross-clamps the aorta.

Gonzo reenters and sticks his thumb up. The room applauds has Hall spins around in her seat, slapping palms with her colleagues. “Guys, we got a heart!

The clock starts when the blood stops. Each organ has a different ischemic time, how long it can survive without blood flowing to it. The heart has about four hours out of the body until its cells begin to die and it becomes unusable. The lungs have up to six hours, the liver between six to 10, and the pancreas as many as 18. This determines the order in which they come out.

Cervantes, the surgical coordinator with Southwest Transplant Alliance, rushes in after the aorta is cross-clamped, dumping sterilized ice into the open chest cavity to help preserve the organs. Malyala squares his shoulders over the chest and leans in with the blade. It doesn’t take long before the heart is in his hands. He peers at it through a pair of magnifying surgical loupes attached to his glasses to determine whether the organ has a Patent Foramen Ovale (a PFO), meaning there’s a hole in the heart. There isn’t. He pulls the organ carefully into his chest with both hands, walking counterclockwise around the operating table. Schwartz, the thoracic surgeon, begins to remove one of the lungs.

“Have a nice flight,” Malyala says, placing the organ inside a plastic jar filled with solution. He puts that inside a plastic bag and twists it around, pinching the bag closed with calipers, then tying it off with plastic twist ties. He does this once more, and then the whole arrangement goes into the blue cooler with a label that reads “HEART” in capital letters.

For the first time in nearly four hours, the timing of the transplant is no longer in the surgeons’ control.

•••

When I ask Gonzo to describe his relationship with Hall, he quickly likens it to Steven Tyler and Joe Perry of Aerosmith. No, wait, actually, it’s more like Drew Brees and Sean Payton, then, ah, well, really, it’s Bill Belichick and Tom Brady. They’ve won more Super Bowls. “It’s that powerful,” he says, cackling.

What he means is this: Dr. Gonzo will often develop an idea, and Hall will figure out how to pull it off. When he got here, in 2012, Baylor wasn’t staffed to be a high-volume center. Despite this, in the last six weeks of that year, they transplanted 23 hearts. For context, it took all of 2011 just to get to 30. Hall remembers sleeping on an empty ICU bed between procedures. She says their one procurement surgeon only had enough time to drop off a heart before heading back to the airport to go and get another.

“It. Was. Brutal,” Hall says, punctuating each word. “That first six weeks, I thought I was going to die.”

For more than a decade, Baylor didn’t even have its own surgical transplant staff. In 1996, it began a partnership with UT Southwestern. The academic medical center would deploy its heart and lung surgeons to Baylor’s East Dallas flagship to transplant the patients listed there. In the 16 years that the two were linked, Baylor achieved 20-plus transplants over a 12-month period just six times. The Southwestern surgeons were stretched thin. They also performed open-heart surgeries on patients at the Dallas Veterans Affairs Medical Center as well as Parkland. Then they had their own shop back in the Medical District. Hall says they wanted to grow the program, and to do that, she needed her own people.

“We were a good program. We were a modest-sized program,” Hall says, “but I couldn’t get us to where I thought we could be.”

And so in the late 2000s, Hall began pushing for her own surgical team, an initiative that attracted Gonzo to Dallas from the Cleveland Clinic, world renowned for its cardiac care. Gonzo was a young, well-liked star at Cleveland, and his personality even pulled CBS into his orbit. In 2009, the network bought an hour-long drama with a protagonist based on him. (Three Rivers didn’t make it past one season, but Gonzo remains friends with the man who played him, Hawaii Five-0’s Alex O’Loughlin.) His profile was high enough that Cleveland’s The Plain Dealer covered his departure, reporting that “rumors have been circulating for weeks” that the surgeon who is “beloved by patients” would be leaving the historic institution.

But Gonzo felt like a cog. He wanted to be chief of transplantation, and there were a few guys ahead of him in Ohio. Speak to Gonzo for 10 minutes, and you’ll realize that the phrase “wait your turn” is not something that he gives much credence to. He began talking to Baylor in January 2012 and was hired soon after. By April, he had his license to practice in Texas. Three more surgeons—also from the Cleveland Clinic—came on over the next year. The heart contract ended with UT Southwestern on November 15, 2012, and the team got to work.

Of those first 23 patients, 22 survived the one-year period during which they’re most likely to have complications from the transplant—whether that be immunosuppression or infection or outright failure. But despite this, the critics collectively raised an eyebrow and pointed it at Gonzo and Hall. After all, the program had never seen such traffic in such a short amount of time. Those hearts must’ve been turned down by other surgeons for some reason.

“It’s common, right? You bring in something, you have success, and then people start questioning you,” he says. “I’m okay with it. It made the program better, because we started establishing processes that allowed us to document for everybody in the program, to eliminate those rumors when people started questioning our practices.”

To him, those risks weren’t really risks at all. They were a response to an overabundance of caution. The risk was that patients who could’ve gotten a heart were hanging on by the thread of the federal waiting list because the doctors weren’t willing to try. There aren’t many perfect hearts out there. He was confident that he would prove any critics wrong. This is a man who keeps a note from his stepfather on his desk that reads: Nil illegitimi carborundum, a Latin aphorism that roughly translates to “Don’t let the bastards wear you down.”

Through 2015, the center’s one-year survival rate during this growth period hasn’t changed. At around 89 percent, Baylor’s mortality rate is not significantly different from the national average of 90 percent, declared by the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients. Armed with this data, the administration dedicated resources to building the program. Baylor has more than doubled its transplant cardiologists, going from just three in 2013 to seven in 2015. There are now five surgeons, up from three in 2013. The program has added five nurse practitioners since 2010 and another two coordinators, bringing the total to five. Baylor also spent more than $4 million on a new clinic and administrative offices solely for the transplant program.

Here is an example of how far Baylor has come. Late last year, Gonzo was doing rounds in his office. While flipping through one file, he noticed that the patient had been referred by the Texas Heart Institute. This is the institution that pioneered open-heart surgery behind Drs. Michael Debakey and Denton Cooley. It was there, in 1966, that the world’s first artificial heart—an LVAD—was implanted successfully in a patient. Gonzo looked up from the folder.

“Huh,” he said, smirking, “Texas Heart is sending us their patients.”

•••

I peer into Charlie Robbins’ chest before I am able to see his face. We landed near Love Field about 20 minutes earlier. Malyala and Dr. Samuel Jacob, a surgical fellow, deplaned first. Jacob clutched the cooler with the heart and jogged toward a Baylor police car. He put the icebox in the backseat and climbed in after it. Malyala got up front. The cop escorting us hit the sirens and sped off toward Cedar Springs Road, destined for the Roberts Hospital at Baylor.

Robbins’ face and neck and lower extremities are covered with a blue tarp. His chest is splayed open and held wide apart by metal clamps. The top layer of the skin is Dijon yellow, the dermis below it an inch-thick chunk of dark red. He is connected to a cardiopulmonary bypass machine, which regulates his breathing and his blood flow while there is no heart in his chest. His yellowing, shriveled heart had already been cut out and rests in a blue bowl on a metal tray near his feet, next to the bolt-shaped LVAD that helped his weak organ function. There is no operating theater. I stand next to the anesthesiologist, clutching my reporter’s notebook. Robbins’ chest is open no more than 3 feet below where I stand.

It is after midnight on a fall Tuesday morning. Dr. Gonzo already transplanted another patient’s heart about 12 hours earlier. He looks weary but focused, uncharacteristically quiet. When the cooler arrives, the surgeons confirm the cross match, meaning that Robbins’ antibodies will not attack the new, foreign heart. Gonzo begins, placing the heart about 8 inches down into the cavity. The room is silent save for a mix of alternative rock from the ’90s—The Smashing Pumpkins, Soundgarden, Nirvana—that plays quietly through a small speaker. The little talking the doctors do is strictly utility; Gonzo needs forceps or wants the robotic operating table shifted up or down.

“The reason we change the direction in which the patient is lying is that inevitably there’s air trapped in the donor’s aorta,” Gonzo says. “It’s easier to get it released and out of the blood system. If air rushes into your brain, you have seizures.”

He uses royal-blue thread to delicately stitch together Robbins’ aorta and the donor’s. He often has to cauterize tissue to make the two fit together, something he describes as “almost like cardiac reconstructive surgery.” Robbins’ aorta, which resembles a water hose made of flesh, is thicker than that of the donor’s. And that’s about as tricky as it gets. This is, as Gonzo likes to put it, the easy part. He’s connecting tubes. The legwork—verifying that the organ is healthy, removing it safely, getting it out of the donor and to the recipient in less than four hours—is all done.

After he’s done stitching, Gonzo begins to slowly release the cross clamp on the aorta, which Malyala applied to stop the blood flow. Gonzo leans over the body and appears to palm the heart. Blood rushes into the coronary arteries and fills the chest cavity. The heart comes alive. Robbins’ pulse builds—90 then 100 then 110 then 120. Gonzo looks up.

“That’s it,” he says. He steps away, pulls his blue gloves off and trashes them. The Foo Fighters’ “Times Like These” comes through the speaker.

“It’s times like these you learn to live again,” Gonzo says, quoting the song’s lyrics. “I didn’t plan for that one. But I guess it’s no ‘Kickstart My Heart.’ ”

•••

With the advent of better immunosuppressive drugs and advanced surgical techniques, transplantation has matured into an almost routine fixture for any number of ailments that were previously thought to be fatal. Recipients who are on the federal waiting list are separated into 58 regions, each manned by an organ procurement organization, those OPOs. North Texas is under the auspices of the Southwest Transplant Alliance, along with areas that include coverage from El Paso to Galveston. When a heart becomes available in, say, Plano, coordinators with STA learn the patient’s blood type and then begin running tests to determine whether the organs are healthy enough to be used in a transplant. They offer the organ to the patient in their region in the most severe condition who has been on the list the longest. It’s a process that is meant to wipe away all subjectivity—your race and economic standing no longer matter. All that does matter is your body: where it is, how healthy it is, how long it’s been on that list.

But the demand has long outpaced the supply. There are more than 122,000 people awaiting some type of organ transplant, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. In 2015, surgeons set a record by transplanting 30,973 organs. That only met about a quarter of the need in the United States. Because of this dearth of donors, an estimated 22 people die each day awaiting an organ.

And because of this, Baylor shies away from any sort of blanket criteria that would deny a donor because of age or size or lifestyle. Gonzo has added nuance to the rules. He’ll run tests for viruses, research the patient’s history and the cause of death. He’ll study the heart. Gonzo says about 20 percent of the hearts Baylor transplants are defined as “high risk” for social behaviors by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—they’ve come from donors who may have been drug users, spent recent time in jail, or were sexually promiscuous. The recipient has to agree to be transplanted with a high-risk heart. With the stakes literally do or die, the majority agree.

“The one thing I love about transplant is that it’s an art. There’s clearly a lot of science there, but the magic is the art of it,” Hall says. “How many risk factors do you accept? It depends on the donor and the recipient and the individual situation. That’s what Gonzo and I are so in sync with. We have that same philosophy. I thought I was aggressive and proactive about getting donors until he came.”

From 1997 to 2007, Baylor’s volume trailed Medical City Dallas Hospital, which did the most transplants in the region annually. Hall’s husband is Dr. Rick Snyder, the medical director for advanced heart failure and cardiac program development at Medical City, making their relationship, as he puts it, “a veritable James Carville-Mary Matalin.” Snyder’s shop is a little more conservative about its outcomes because of its volume and, he says, the long-term well-being of its patients.

“The fact that they’re pushing the envelope and challenging some of the conventional wisdom that you shouldn’t take a heart that’s this old or has this much ischemia time or whatever little issues you’re thinking about, I think they should be commended,” says Snyder, who is also a former president of the Dallas County Medical Society. “This is what we should be doing in medicine.”

Baylor’s volume gives the center some room to transplant riskier patients who may have been turned away elsewhere because of weight or age or acuity. They’re willing to travel to other regions when hospitals turn down the hearts. The vast majority of centers do fewer than 20 transplants a year, which spurs conservatism. A single death could torpedo their mandated one-year survival rates. But donor hearts that centers are receiving aren’t getting any healthier.

In 2015, American centers transplanted 2,819 hearts. Considering that Baylor and other high-volume centers like Cedars-Sinai are maintaining one-year survival rates near 90 percent, the risk of losing lives by turning down hearts is greater than the risk of the patient rejecting the heart. By the time the surgeons are ready to transplant, Gonzo and Hall are always confident that the heart will take. If they aren’t, they walk away.

“Our donors are older. They have more illnesses,” Hall says. “We don’t have the young—and this sounds morbid—but we don’t have as many of the 20-year-old gunshot wound to the heads, or the 20-year-old motorcycle accident deaths because they weren’t wearing a helmet. They’re now in their 30s and 40s with hypertension. They die of head bleeds or complex traumas or strokes, so the donors are less healthy. Ten to 15 years ago, we would’ve denied all those donors. If we do that nowadays, we would halve our [national] volume to 1,000 a year.”

•••

Charlie Robbins has a neatly cropped head of gray hair. He has broad shoulders and a square jaw, though that is tough to tell while speaking to him in a conference room at Baylor University Medical Center: his words come through a surgical mask. It is about two weeks after his surgery, and, outside of some standard fluid accumulation, he’s doing well.

His wife, Shirley, sits next to him. There are tears in her eyes. Charlie spent two years on the list at Ochsner Medical Center in New Orleans, at least some of that time likely made possible by the LVAD. That metal pump helped keep his bad heart pumping, but it was only meant to be a bridge before transplant. In 2006, he had a defibrillator put in to regulate his heartbeat. In 2012, doctors reopened his chest to fix a leaking valve but couldn’t, opting instead to put a surgical band around it. “From that point on, I really started going down,” Charlie remembers. In April 2013, he had the LVAD put in. He was added to the transplant list six months later.

After a year, Shirley got anxious and asked the doctor about how much longer his name would float on the list.

“The doctor said, ‘Well, you’ve gotta look at it like this. If he didn’t have the LVAD, he wouldn’t be here today,’ ” Shirley says.

But that worked both ways, she thought: there’s also no telling when his heart would finally give out. Maybe the delay was because of his age or the complication of a fourth open-heart surgery. It also may have been because of his O-positive blood type. O-types wait the longest: bodies will reject organs that aren’t also O. Too, Ochsner is also one of the many centers that performs only about 20 heart transplants each year. Maybe they were worried about the risk against their mortality rate.

Shirley vented about all this to her pain management specialist, who suggested double-listing. Patients can’t dual-list at two centers in the same region, but they’re welcome to appeal to a program beyond it to get listed there. So Shirley and Charlie went back to their doctor and asked.

“She said, ‘I hear Dallas is pretty good,’ ” Shirley remembers.

Charlie and Shirley Robbins contacted Baylor on September 19. After languishing on a list at another center, Charlie’s new heart was beating in his chest by October 20. He is the type of patient that Baylor built its program to serve. Meanwhile, the strength of Baylor’s outcomes and volumes has brought relationships with other institutions. Texas Heart is sending it patients and so is Ochsner, so is the Cleveland Clinic, so is the University of Minnesota Medical Center, so is The Heart Institute at St. Joseph Medical Center in Maryland. Baylor is continuing to send cardiologists to other states to create more allegiances and get more patients like Charlie to Dallas.

As the new heart beat in Robbins’ open chest that October morning, Gonzo walked out of the operating room and into the lobby. He met Shirley’s eyes. She spoke first.

“We’re good,” she said, her voice more resolute than concerned.

“Yeah,” Gonzo replied. “We’re good.”

Write to [email protected].