Cynthia Mulcahy and Lauren Woods arrived at Dallas City Hall one morning in February ready for a fight. A few weeks earlier, Mulcahy, an artist, curator, and former art dealer, had happened upon a seemingly innocuous item on a subcommittee agenda of the Park and Recreation Board. The board, the item said, would consider the acceptance of a gift of historical park markers on behalf of the Boone Family Foundation and the Rainwater Charitable Foundation. Mulcahy was stunned.

When she and Woods tracked down the subcommittee briefing, their worst fears were confirmed. The gift consisted of seven historical markers that were to be installed at parks that had been designed during segregation for use only by blacks. Included in the briefing were samples of the texts that would appear on those signs. Those texts were poorly edited versions of the same park histories Mulcahy and Woods had spent the better part of a year researching and writing. Important black history, information shedding light on how the white establishment in Dallas had fostered segregation, had been swept aside.

Hall Street Park and the Oak Cliff Negro Park were never officially segregated. In early 20th-century Dallas, segregation was so ingrained in the city’s culture that it didn’t require legislation.

Now that it appeared that the foundations were attempting to advance the project on their own—with a co-opted version of the artists’ research—Mulcahy and Woods went down to City Hall to raise hell. But they didn’t get a chance to speak their mind. A few minutes before the meeting began, a city staffer leaned over Mulcahy’s shoulder. “The item was tabled,” the staff member whispered. The board would consider it at a later date.

The artists looked around the sixth-floor conference room. All the gray chairs in the small public gallery were empty. No one had come to represent the foundations, which could only mean that the foundations had somehow already known that the agenda item wouldn’t be addressed that morning. The artists left City Hall that day with the same questions that had been nagging at them for more than a year. Who was trying to keep them from publishing their history of the parks, and why on earth were they doing it?

•••

Mulcahy and Woods pored over municipal, state, and university archives. They interviewed older Dallasites and combed through personal photos and archives. They dug through a century of park board minutes, searching for clues that would explain why, in 1915, the city of Dallas decided to create two parks, Hall Street Park (now Griggs Park) and Oak Cliff Negro Park (now Eloise Lundy Recreation Center), for use solely by blacks.

The artists discovered that piecing together a historical narrative of the black experience in Dallas would be complicated. The Ku Klux Klan was a powerful force in Dallas politics in the first decades of the 20th century, and the major daily newspapers at the time were written and edited from a decidedly white perspective. In a segregated city like Dallas, African-American voices enter the public record only in snippets and sidelong references. And the tenor of public discourse between the white and black communities was characterized by a decorum that belied the tension and threat of violence that simmered beneath the surface.

“It’s all Southern courtesy,” Woods says. “ ‘We’re good, liberty-loving people, and we know you are, too, and so it would be great if we could just have a levee so we don’t die.’ ”

But as the artists turned to the black press, the Dallas Express in particular, they found evidence of black communities beginning to organize in new ways. In the 1910s, housing for blacks was largely confined to two neighborhoods, North Dallas (State-Thomas) and Deep Ellum. Other African-Americans settled in unincorporated slums on the west side of the Trinity River.

Woods says they found some documentation of African-Americans trying—and failing—to buy private land in Deep Ellum to set aside as public space in the early 1900s. But any effort by the black community to lobby the city for their portion of a 1913 city bond that raised $500,000 for parks must be inferred from innocuous references, like a line item in the park board minutes from August 18, 1914, which reports, “W.L. Diamond and other Oak Cliffites are interested in the matter [of the new parks].”

There are no records of the conversations that followed Diamond’s expression of “interest,” but Mulcahy and Woods read that statement as evidence of a nascent black political voice rising into the public dialogue like oxygen bubbles popping on the surface of a lake. At the time of the city bond election, the violence facing the black community was all too real. The memory of the 1910 lynching of Allen Brooks, whose dead body hung from the Elks Arch of Honor, which once spanned the intersection of Main and Akard streets, was still fresh. It was in this environment that, in 1915, the city deemed it appropriate to create the two new parks for use by blacks.

Mayor Pro Tem Charles G. Stubbs tried to temper their anger by proposing the creation of a separate, all-black city that would be “half the size of Waco and three times the size of Highland Park.”

“[The parks] were a way to forestall integration,” Michael Phillips, the author of White Metropolis: Race, Ethnicity, and Religion in Dallas, 1841-2001, told the Morning News in 2014. “They were a safety valve.”

•••

In the 1920s, the black community began to expand into neighborhoods south of downtown. A third Negro park, Wheatley Park, was created on a postage stamp-size lot adjacent to the Oakland Cemetery, a spot chosen only after previous attempts to set aside a larger area for a Negro park were met with resistance from white residents.

By the 1930s, the black community had begun to establish a stronger voice in civic affairs. In 1932, a dynamic young lawyer named Antonio Maceo Smith returned to his hometown of Dallas after earning graduate degrees at New York University and Columbia. Smith became the first executive secretary of the Dallas Black Chamber of Commerce, originally called the Dallas Negro Chamber. From his office in the State-Thomas District (known then as North Dallas), Smith built the chamber into an effective political institution, a model for similar organizations around the nation, as evidenced by correspondence uncovered by Mulcahy and Woods.

By the mid-1930s, the black voting bloc was large enough that local politicians could no longer ignore it. Black civic groups also became increasingly effective in having their voice heard. The Oak Cliff Civic League petitioned the city for a new park in Oak Cliff, and in 1938, Eighth Street Park was created. Two years after the park’s founding, it was rededicated and renamed for Will Moore, an early community activist with the NAACP, during a Juneteenth celebration that also honored the handful of elders left in the community who were freed slaves.

Still, victories came with reminders of the power of the dominant culture. After the establishment of Moore Park, a white real estate developer petitioned the city to intervene in what he perceived to be an attack on the value of his adjacent subdivision, arguing that “there will be a crowd of Negroes always congregating around these trees” and that “the Negro park and the advertising it got certainly is hurting my sales.” The city sided with the landowner and carved off a few acres of the new park to create a buffer between his all-white subdivision and the new “Negro-designated” park.

Such open contempt is hard to find in historical documents, but a close reading shows that the city was filled with points of friction. For example, beginning in the 1930s, letters begin to show up in the city archives from black residents requesting that the city designate another public space, Wahoo Lake, as a Negro park. The site of an old fishing and hunting club in the 19th century, Wahoo Lake was being used by black and white citizens, who kept to opposite sides of the lake.

“You have to infer that something was happening that the black community would keep coming back and saying, ‘Would you please designate this a Negro park?’ ” Woods says. “Something was happening, but they are not documenting what exactly the conflicts were. Is it so hard to believe that black people didn’t want to be around white people?”

In 1935, the city finally designated Wahoo Lake “Negro.”

Juneeta boyd’s grandparents moved in the 1920s from East Texas to Dallas and took up residence in a little shotgun shack steps from Oak Cliff Negro Park, in the Bottoms. Boyd’s mother grew up in that house, and she did, too, born into a world that, in 1947, hadn’t changed much from the one her grandparents experienced two decades prior. The Bottoms in the ’40s and ’50s was the kind of community where everyone’s parents knew each other, where kids behaved themselves because they knew some adult somewhere had an eye on them.

“That was back then, when the whole community would raise you,” she says. “We had the church in the community, but mainly everyone went to the park.”

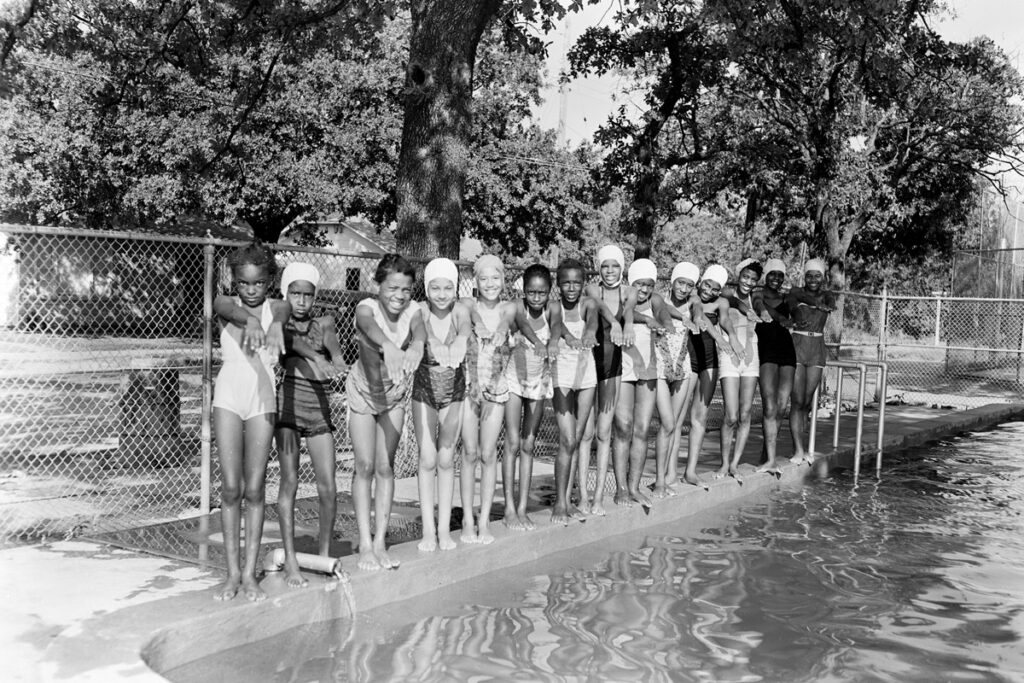

Boyd’s life revolved around Oak Cliff Negro Park. At the park, there were baseball and softball tournaments; Friday night square dances; dominoes and checkers lessons. A pageant each year was held to name Miss Oak Cliff Park, an honor given to Boyd in her early teens. She headed to the park every day after school, where she would take ceramics classes at the rec center and play softball and table tennis. In 1963, after defeating all of the kids in her own neighborhood at table tennis, Boyd sat in the back of a Dallas bus and rode across town to Exline Park, in South Dallas, where she beat all the kids in that neighborhood as well.

“I only played blacks,” she says. “But I still got the trophy for the city championship, because I won the most games.”

Sometimes Boyd and her friends would walk down to the levee to watch baseball games at Burnett Field. Her uncle played for the Dallas Black Giants, alongside Negro league star Bill Blair. Boyd and her friends salvaged cardboard boxes and used them like sleds to slide down the levee banks. After heavy rains, when the Trinity River flooded, Boyd and her friends sat on the levees, took off their shoes, and dipped their feet in the water.

The Bottoms has always had an intimate relationship with the Trinity River. Before the levees were built, the neighborhood flooded regularly. T-Bone Walker, who got his start performing in Oak Cliff Negro Park, wrote “Trinity River Blues” about the dirty waters that would regularly rise up and swamp the neighborhood.

“I lost all my clothes, baby,” Walker sang. “And I think I’m going to lose my mind.”

When Boyd’s mother learned her daughter was dipping her feet in the Trinity, she warned her that there were snakes in the water. After that, Boyd stopped putting her feet in the river. Her mother warned her about other dangers, too, telling her to sit in the back of the bus if she didn’t want any trouble. When she was 13, she saw a Hispanic man walking through the park. It was the first time she remembers seeing someone who wasn’t black in her neighborhood. The man came up to her at a water fountain and made a lewd comment.

“I looked at him and I ran,” Boyd says. “We were startled to see another race down there.”

Boyd’s insular world in the Bottoms kept her ignorant of the conflicts that were escalating in other parts of the city, but the adults in her neighborhood whispered on front porches about bombings in South Dallas. The black press reported that marauding bands of white teenagers drove in the streets around Exline Park, hurling insults and firecrackers at black residents.

In February 1950, tensions in South Dallas reached a breaking point. Mayor Pro Tem Charles G. Stubbs attended a public meeting of white South Dallas residents and tried to temper their anger by proposing the creation of a separate, all-black city that would be “half the size of Waco and three times the size of Highland Park.” According to the Morning News report at the time, that wasn’t enough to appease the whites. At the end of the meeting, Vernon L. Barr, pastor of the South Harwood Baptist Church, leapt to his feet and addressed the crowd.

“Don’t scare,” he told the all-white audience. “If anybody’s going to get scared, let it be the Negroes. God never did mean that Negroes and whites should live together. The Bible says it isn’t so.”

The bombings, attacks, and threats continued, and in the early 1950s, the front line in the fight to maintain Dallas’ strict racial divide was drawn across Exline Park.

•••

If you were a young black boy growing up in South Dallas in the ’40s and ’50s, it was too dangerous for your Boy Scout troop to meet in Exline Park. Instead, you piled into a car with the Reverend A.C. Horton, the longest-serving pastor of Mt. Carmel Missionary Baptist Church, and headed over to Moore Park, where the Reverend Horton taught his boys to fish and play golf, and where he held his annual Easter egg hunts for the neighborhood children.

As a little girl, Horton’s granddaughter, Felicia Agent, was oblivious to the long battle that had been waged over the park that sat blocks away from her house on Metropolitan Avenue. In 1939, Ku Klux Klan leaflets were distributed at a public meeting where the Reverend John G. Moore, pastor of Colonial Baptist Church, claimed, “The Negroes have made their boasts that in two years’ time they will have this very school for their own and Exline Park as well.” In 1941, the park board approved the construction of a fence through Exline to “eliminate some sources of interracial trouble in South Dallas.” In 1953, Exline Park and the adjacent Charles Rice Elementary were redesignated for blacks.

In his 1986 book The Accommodation, Dallas Observer columnist Jim Schutze places this ceding of South Dallas within the context of a more broad-based effort by Dallas’ business-minded, image-obsessed white elite to keep the peace while forestalling true integration and diminishing the political agency of its black citizens (a move, Schutze argues, with which some members of the black leadership were complicit). All 6-year-old Felicia Agent knew was that in 1953 her mother got a job as a teacher at Charles Rice Elementary, and after school she would sit on the swings at Exline Park and wait for her mother to get off work.

“I’m thinking, ‘Oh, Exline, let me find this black man,’ ” she says. “But Exline was white.” Agent found the descendants of Exline, but they refused to come to the ceremony. “They turned us down now that it is a black park.”

Even though segregation officially ended with the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Agent still speaks of it in present tense. She sees it as something that her own children, born in the 1980s, had to overcome. When Agent noticed that her children were getting A’s in public school without having to study, she had them test into St. Mark’s and Hockaday, and they both earned scholarships.

“My children had an opportunity to get out of segregation,” she says. “I worked hard getting them through, but they did get through.”

Agent still sees segregation in the inadequate DART Paratransit Services she relies on to get from her home at Buckner Terrace to her kidney dialysis treatments each week. On the day we meet, she skipped her treatment because the previous Friday she had waited four hours for a DART bus that never came. There’s a house two blocks down the street from Agent that has two Confederate flags flying from a second-story balcony. When she sees those flags, I ask her, what does she think about?

Agent tells a story about Exline Park. In the 1990s, she led an effort to renovate the rec center, which hadn’t been updated since it was built in the 1940s, when the park was still whites-only. After some discussion in the community, they decided not to rename the park. The name “Exline” had come to mean too much for the community in South Dallas. It bore with it the history of their struggle, the source of their pride. So Agent decided to track down the source of the name to see if the descendants of the park’s namesake would come to the rededication ceremony.

“I’m thinking, ‘Oh, Exline, let me find this black man,’ ” she says. “But Exline was white.” Agent found the descendants of Exline, but they refused to come to the ceremony. “They turned us down now that it is a black park.”

Agent explains that until she met Woods a couple of years ago when the artist came around asking questions for the marker project, she never knew that Exline was a “Negro-designated” park. For all of Agent’s life, all those years she dedicated herself to serving the park and the people who used it, she had always simply thought of Exline as her neighborhood park.

“Negro park,” Agent says, taking a long pause to stew on the phrase. “We have been called so many things: ‘colored,’ ‘boy,’ ‘black,’ ‘African-American.’ You don’t know what you are. I found out I was Cuban. I didn’t know it. My father’s people were from Cuba.”

Agent reels back in her wheelchair and coughs into her arm.

“Now that I’m having to think of integration and segregation, it opens my eyes to a lot of things,” she says, “things that you don’t normally see, think about.

“I think of how far we have gone. But we haven’t gone very far.”

•••

“This is a question of who gets to write the public history,” Woods told the park board that morning. “Who will write the public history? This is an issue our city has struggled with for too long.”

After the artists spoke, park board president Max Wells read a statement from Garrett Boone, founder of The Container Store and president of the Boone Family Foundation. The foundation would remove itself from the marker project, Boone said, blaming the conflict, in part, on confusion over the length of the park markers and defending his foundation’s willingness to confront the full history of Dallas’ Negro parks. It wasn’t a victory, exactly. Wells said the park board would move forward with drafting an ordinance that will codify the appropriate length of historical markers in Dallas parks. Mulcahy and Woods continue to engage city staff and park board members, hoping to advance the marker project and demonstrate that other cities—as well as other parks and districts in Dallas—do not restrict the telling of their histories to the arbitrary length of 250 words.

But in the wake of the controversy, one troubling question lingers. Were the foundations reluctant to include references to some of the more uncomfortable historical details that Mulcahy and Woods included in their texts? The executive directors of the two foundations did not answer requests for comment, but when you look at the original texts that the artists produced and compare them to the texts submitted to the park board foundation, the omissions tell a story. The omissions include the story of the white real estate developer’s anti-Negro buffer around Moore Park, the controversy over use of Wahoo Lake, and even T-Bone Walker’s performances of “Trinity River Blues” in Oak Cliff Negro Park. But the most telling omission is a line that the artists made sure to include in each of their markers, a reminder that the city never legally segregated its parks. Instead the marker would read: “Conventions of dominant culture were rigid enough to enforce and privilege ‘White Only’ use of public facilities.”

The ordeal over the markers illustrates why writing Dallas’ racial history is so difficult and why understanding it is so vitally important. In Dallas, segregation wasn’t merely the project of a regime backed by an ugly ideology. It was a cultural reality embraced, however reluctantly, by both white and black communities. It was a social compromise that covered up a prevailing attitude in which whites perceived blacks as less than human, and blacks feared the physical violence that this dehumanization portended. If segregation in Dallas was convention and not law, then its abolition in 1964 was not enough to end it—along with the hatred and prejudice that attends it.

Why exclude that important fact about Dallas history? One could interpret the omission as the protective impulse of a brand-conscious corporate mindset. But perhaps something else was at play. Perhaps the foundations’ unnamed editor believed that cutting the ugly aspects of the history from the public signage was a way of respecting those who grew up loving their parks. Perhaps it was a gesture intended to be polite—polite to people like Juneeta Boyd, with her stories of playing along the Trinity River levees. The well-meaning editor simply wanted to separate the good history from the bad. But history doesn’t allow for such a separation. Joy and suffering exist in tandem in the telling of the story of the Negro parks. Celebration and violence go hand in hand. Whatever peace the parks maintained, they existed in a world that was surrounded by hatred.

There was certainly joy and warmth found in Dallas’ Negro parks. The insular world Boyd describes in the Bottoms in the ’50s and early ’60s shimmers in her childhood memory as a kind of black paradise. She says that she never encountered prejudice while she was in the Bottoms. After graduating from Franklin D. Roosevelt High School and taking a job in a bank, she was hired as one of only five black women in the company. Only then did she begin to feel disdain from some of her co-workers because of the color of her skin.

I ask Boyd about the controversy surrounding Mulcahy and Woods’ project, about her love of Oak Cliff Negro Park, and about how we should tell its history. Is it enough to talk about the picnics, games, and celebrations on the public signs? Should we reserve our discussion of segregation to more appropriate, penitential arenas of discourse?

“It’s history, and I believe in sharing history,” she says. “We didn’t have that. They talk about the South Dallas bombings. We didn’t see it. I can only tell you the good part, because I didn’t have any bad part. Some people, they don’t want to talk about race, but that’s history. There’s nothing wrong with talking about it. People need to know.”