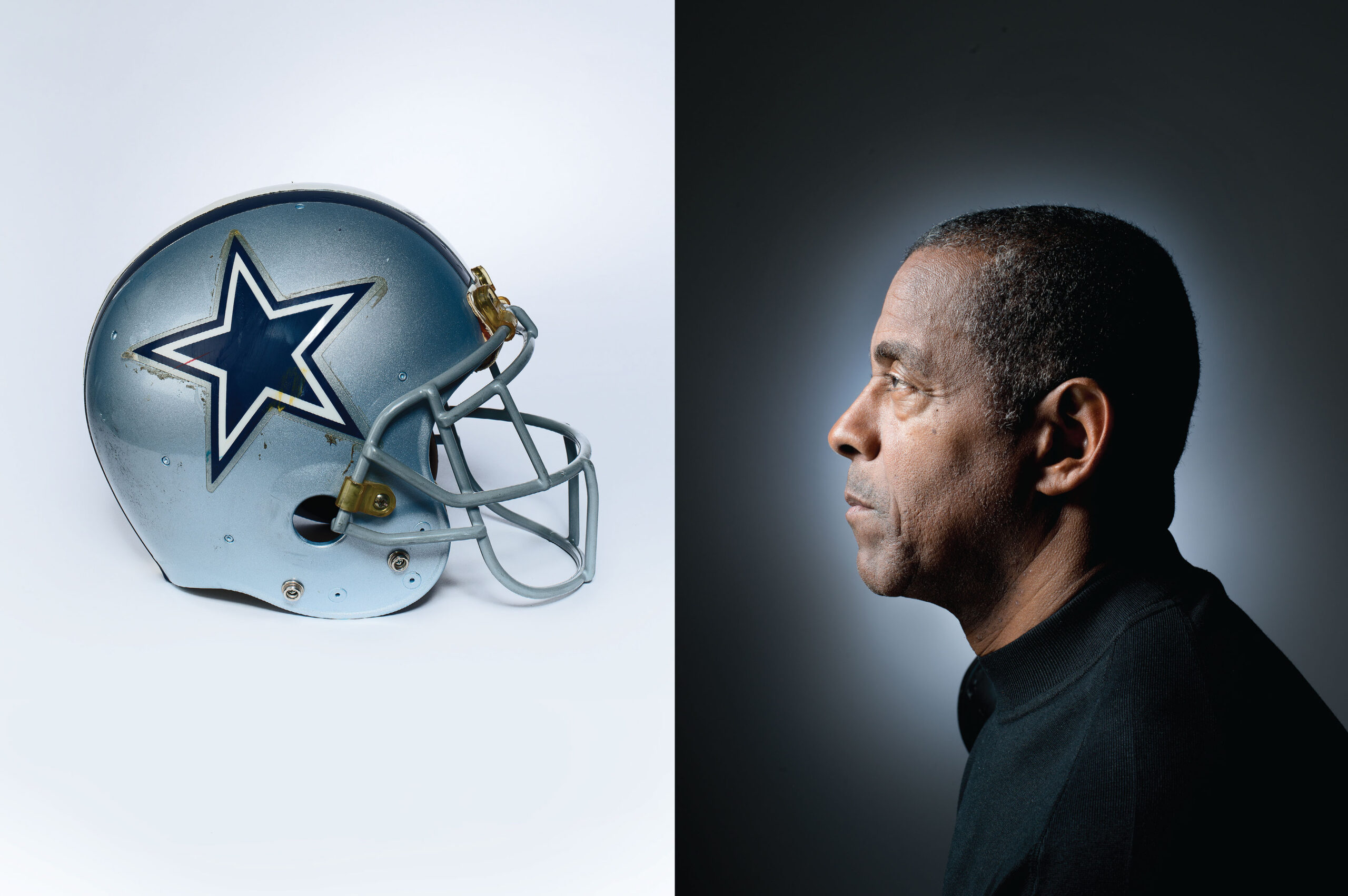

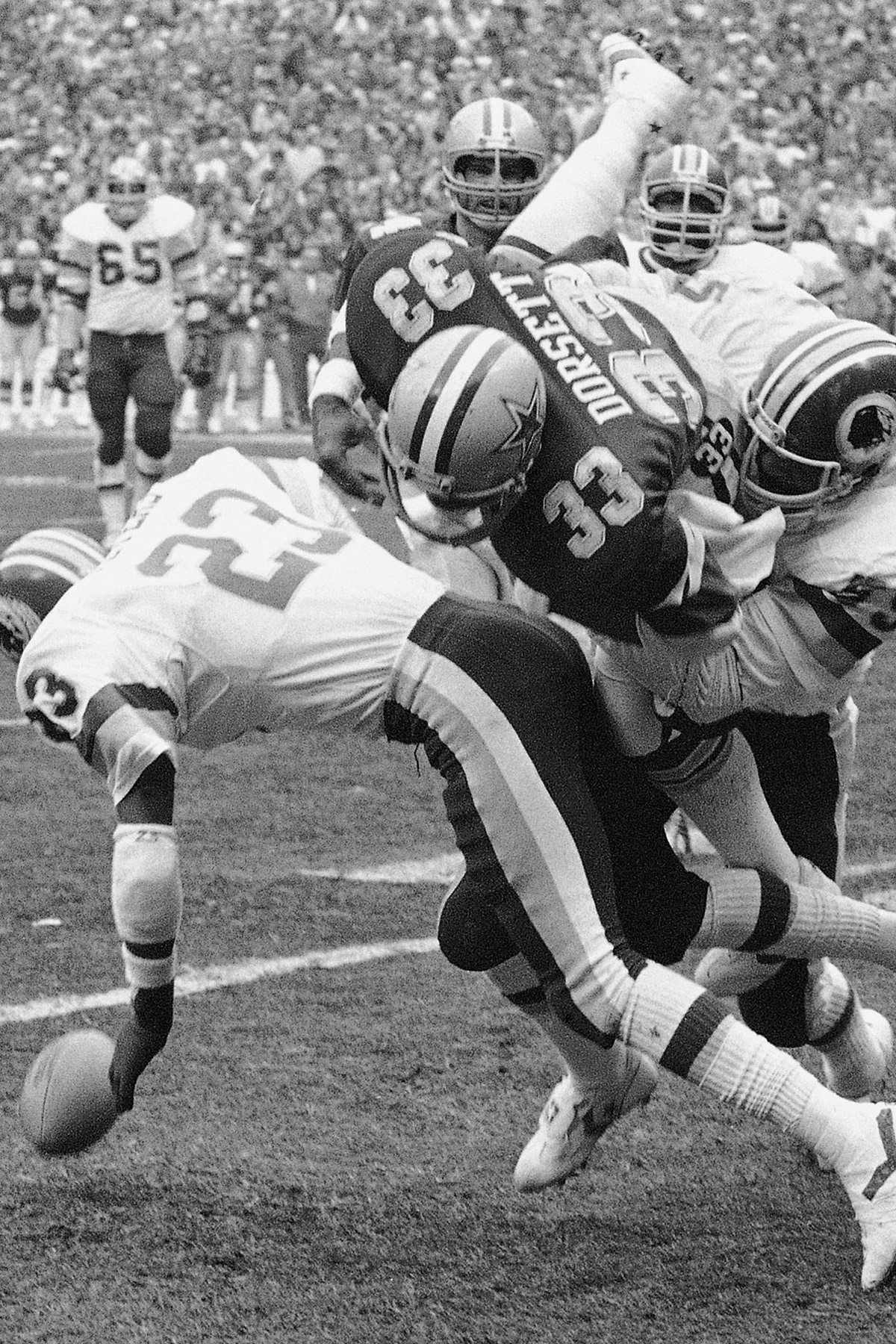

It was January 3, 1983, the last day of the NFL’s strike-shortened season, and Tony Dorsett’s Dallas Cowboys were losing to the Minnesota Vikings on Monday Night Football. A fumbled punt had the Cowboys trapped deep in their own territory, the ball a few inches outside the end zone.

It was January 3, 1983, the last day of the NFL’s strike-shortened season, and Tony Dorsett’s Dallas Cowboys were losing to the Minnesota Vikings on Monday Night Football. A fumbled punt had the Cowboys trapped deep in their own territory, the ball a few inches outside the end zone.

And the Cowboys were out-manned. Fullback Ron Springs didn’t hear what play they were going to run, so he was still on the sideline, leaving only 10 Cowboys on the field and Dorsett all alone in the backfield.

The Vikings were in their goal-line defense, bunched up around the line of scrimmage, gunning for a safety.

Do you remember? Tony Dorsett does.

The call was for a run—“Dive 21,” Dorsett says—that would take Dorsett straight up the gut of the defense, between center Tom Rafferty and guard Herb Scott.

“When you’re backed up that far, you just want to tighten up your chinstrap a little bit, because you know they know you can’t get too tricky, too fancy,” Dorsett says. “You just figure, I’m gonna get a good shot, so just get ready for it.”

That shot never came. Rafferty hit defensive tackle James White, turning him around, out of the play. Scott paused to let Rafferty by, then fired out to his right to seal off linebacker Dennis Johnson. They created a giant opening in the middle of the defense.

“Man, I got great blocks from Herb Scott and Tom Rafferty,” Dorsett says. He is almost hovering above his seat in the living room of his Frisco home, eyes wide as he narrates the play, calling every block and cut. He is right there again. “And I jumped through that hole.”

After skipping over Scott’s outstretched leg, he burst 10 yards up the field before veering to his right, heading for the sideline. “I run to daylight,” he says, “just like I was always taught. I run to daylight.”

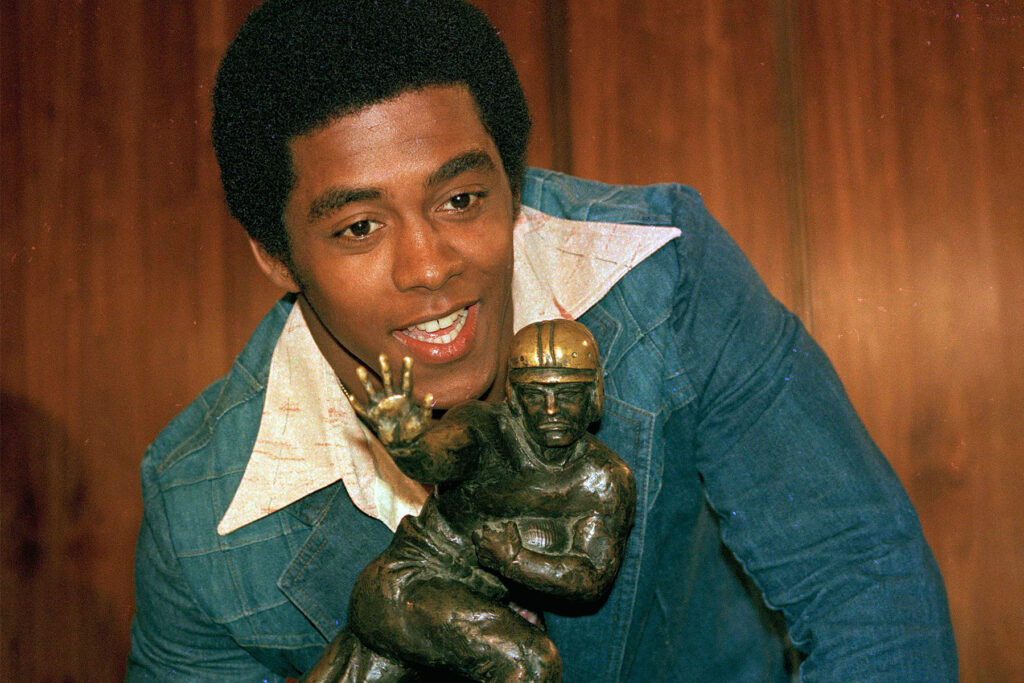

Dorsett grew up wanting to be a running back like his older brothers at Hopewell High School in Alquippa, Pennsylvania. But he wasn’t like them. He was better. What pushed him further than Melvin, Ernie, Tyrone, and Keith—to three All-American selections and the Heisman Trophy in 1976, to the Cowboys and the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1994—was his mind. He studied his playbook until he was prepared for every outcome. He visualized himself in every situation, until he felt like he’d already been through it.

“And your recall is like—bam—nanoseconds,” he says. “Bam.”

Do you remember? Tony Dorsett does.

But even if you were inclined to lazily resort to cliche and say he remembers this play from 30 years ago like it was yesterday, you can’t. Because Dorsett doesn’t remember what he did yesterday. He has days where he wonders how he got here, from a steel town outside of Pittsburgh to a spot in the Cowboys’ Ring of Honor. On the worst days, he literally wonders: How did I get here?

✮

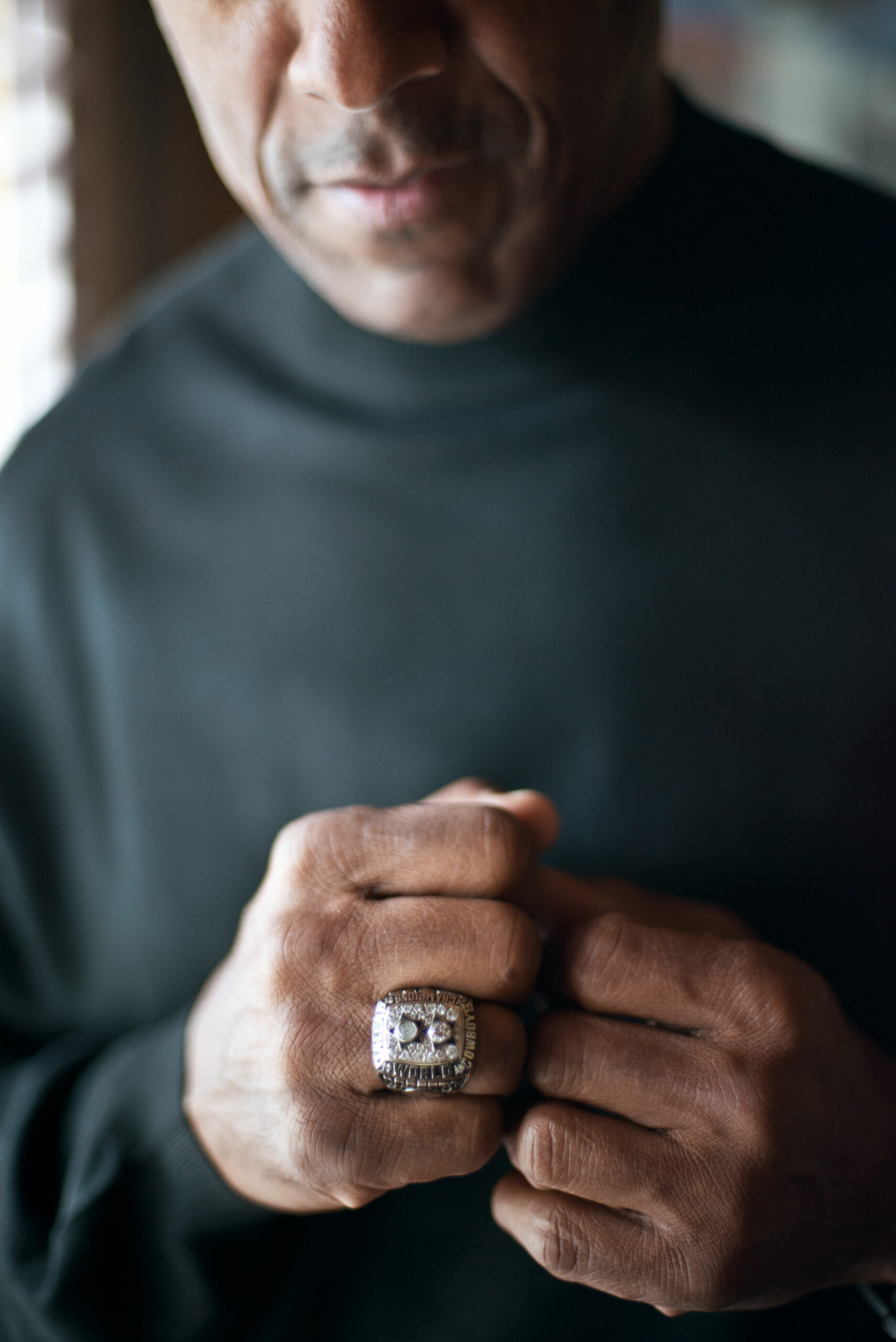

Dorsett moved to Frisco three decades ago, not long after he married his first wife, Julie, back when this area was mostly undeveloped pastureland. He has lived in a gated community a few minutes southwest of Toyota Stadium for the last 10 years or so.

He walks around the bottom floor of the two-story house, opening the blinds, trailed by a tiny, shivering Yorkshire terrier named Charlie. He is in all black—a black, hooded Old Navy sweatshirt; black pants; low-cut black suede boots; and black socks that he habitually pulls up every few minutes. He drops himself into the brown leather chair near a giant TV.

Next to the TV, above the fireplace, hangs a large portrait of Dorsett and his family—his second wife, Janet, and their daughters Jazmyn, Madison, and Mia—dressed alike in white shirts and jeans. It looks like it was taken six or seven years ago. Jazmyn is now out of the house, a senior guard on the Oklahoma State University basketball team. Madison, 15, and Mia, 10, will be home soon.

“My little Madison, boy—she’s an athlete,” he says. Madison plays soccer, and she’s starting to show that certain something that separates good from great, that aggressiveness and extra effort. But her father’s hopes for her athletic future lie elsewhere.

“I seen my daughter run track and my mouth just dropped,” he says. “That’s her? But I was watching her. She don’t even know how to come out of the blocks, but she can roll. I was like, ‘Girl, you are my Olympian. You are going to the Olympics. We going to the Olympics.”

Dorsett says he only ran in a couple of meets when he was a high school senior. He didn’t like it. He ran because he had to, not because he wanted to. “But I could have been a good track guy,” he says. It’s not hard to imagine him at a high school track meet. He is 59 now, 60 in April, but he looks no different than he does in the family portrait, and in the family portrait, he looks much the same as he did when he retired from the NFL after the 1988 season.

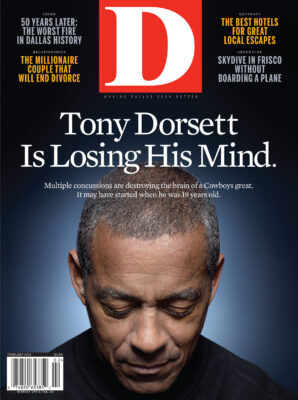

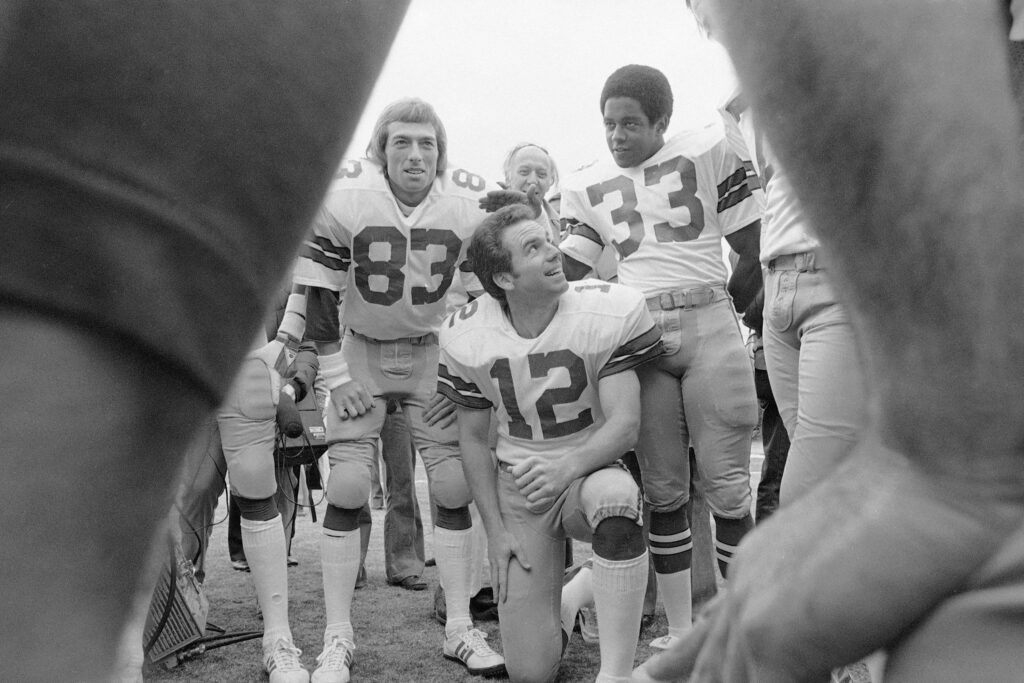

That is part of the reason there was such a strong reaction to news reports in early November that Dorsett’s brain was damaged. But it’s not just that he looks relatively youthful and healthy. He looks the same as he did when he was the charismatic leader of one of the most popular teams in NFL history, the version of the Cowboys first branded America’s Team. That’s why Dorsett rose straight to the top of the 24-hour news cycle, somber present-day clips juxtaposed with some of the brutal hits he took during his playing days, including the one that knocked him unconscious in a 1984 game against the Philadelphia Eagles.

Today, there is a light dusting of gray in his hair, but he still could be the all-caps TONY DORSETT of his playing days, even if he lives a mostly lowercase life now. He doesn’t necessarily look like a former NFL running back—at 5-foot-11 and around 180 pounds, he wasn’t even big enough for that position back when he played—but it’s clear from how he carries himself that he was an athlete. Maybe you’d guess he had been a middleweight boxer if you didn’t know any better.

“Physically, I feel … pretty good.” He says the last two words as though he has only just now considered his condition and is a little surprised by the answer. He had his share of injuries as a player, including a torn ligament in his left knee that ended his final season before it even began. “I mean, I’m still able to get out—I don’t run or jog outside on pavement. I get on an elliptical machine. I can lift some.”

There are former NFL players who can barely walk on artificial hips and knees, whose hands are gnarled by arthritis, who have the range of motion of a department-store mannequin. Dorsett is lucky in that regard. The game didn’t rob him of his body.

But it did take his mind.

✮

Dorsett doesn’t know exactly when he began having trouble remembering things. He didn’t think he’d have to keep track, and what does it matter anyway? It started happening, and then it started happening more, and he still didn’t believe it was happening at all until it was unavoidable. “I was in denial”—he hits the word preacher-hard—“for a long time. Because I was just, ‘Nah, this can’t be happening to me at this age.’ ”

His longtime friend and former teammate Tony Hill recalls Dorsett mentioning over the years that he was starting to forget, that he needed to write things down. But Hill didn’t know how serious it was until Dorsett went public in early 2012, joining more than 4,500 retired players and families of deceased players in a class-action lawsuit (a consolidation of several concurrent suits) against the NFL. (The various plantiff’s attorneys and lawyers for the NFL are currently in the process of finalizing a $765 million settlement.)

“That’s a humbling experience, to acknowledge that there is a deficiency in your life,” Hill says. “People take for granted that we’re entertainers, for lack of a better term, but it’s a very high-risk, high-return profession. There are some severe consequences that are associated with what we do. When you

look at Tony Dorsett on the outside, on the shell, he looks fantastic. I mean, he’s in great shape, he looks good, he’s articulate. But the bottom line is that there is more than meets the eye.”

By 2009, it had become a daily struggle for Dorsett. The practice fields and gyms he had been taking his daughters to all their lives—now he had to stop and ask for directions. A roomful of people he “had been around for a zillion years”—now they were almost strangers, familiar faces with no names attached, the vague familiarity making it worse.

In October, Dorsett boarded a plane bound for Los Angeles. But when he sat down, he couldn’t remember where he was going, or why. He was going to have his brain tested.

“To be, you know, to be—sometimes, man, I would get—it’s the weirdest feeling, man,” he finally settles on. “When I’m out there, I’m on a cloud. It’s like a fog, man. It’s like a fog. That’s the only way I can explain it. I can’t get out of it, and I know—it’s just a weird feeling, dude. I hate it, and I get really, really—and that can make me get real frustrated, if I’m not careful. I get mad at myself for certain things. Not knowing how to get certain places, forgetting where I’m going, driving somewhere then forgetting where I’m going. That kind of craziness, man. So I’ve learned to write notes. Or speak into my phone, write notes on it. Write it down.” He never makes a move unless he has written it down in the planner he keeps at home.

“It’s just a frustrating deal, man. I can become short-tempered, on edge, you know, and that’s not good for a family-type atmosphere, either. It’s not good for that. So if I’m feeling that way, I just gotta get away, just get up in my room. ‘Daddy’s just chilling.’ ” He shakes his head, lets out a kind of soundless laugh. “ ‘Let him chill.’ ”

The sudden bouts of anger were worse than the forgetfulness. His family didn’t understand what would set him off or why, why he would be yelling at his wife or one of his daughters out of nowhere. He didn’t understand. Until Dorsett learned to remove himself from the situation whenever he could, it was paralyzing. Something, anything, nothing would trigger his rage, and then he would turn it on himself: How does something so little just make me blow up like this? I know better than this.

Dorsett is a big believer—and has always told his daughters this—that little things make big things happen. And here he was, unable to take care of the little things. He wasn’t himself anymore, wasn’t the man he had been or the father and husband he wanted to be.

“I said, ‘Something is not right. I don’t know what it is, but something is not right.’ And, finally, when I was diagnosed, it all made sense. It all came together.”

In October, Dorsett boarded a plane bound for Los Angeles. But when he sat down, he couldn’t remember where he was going, or why.

He was going to have his brain tested.

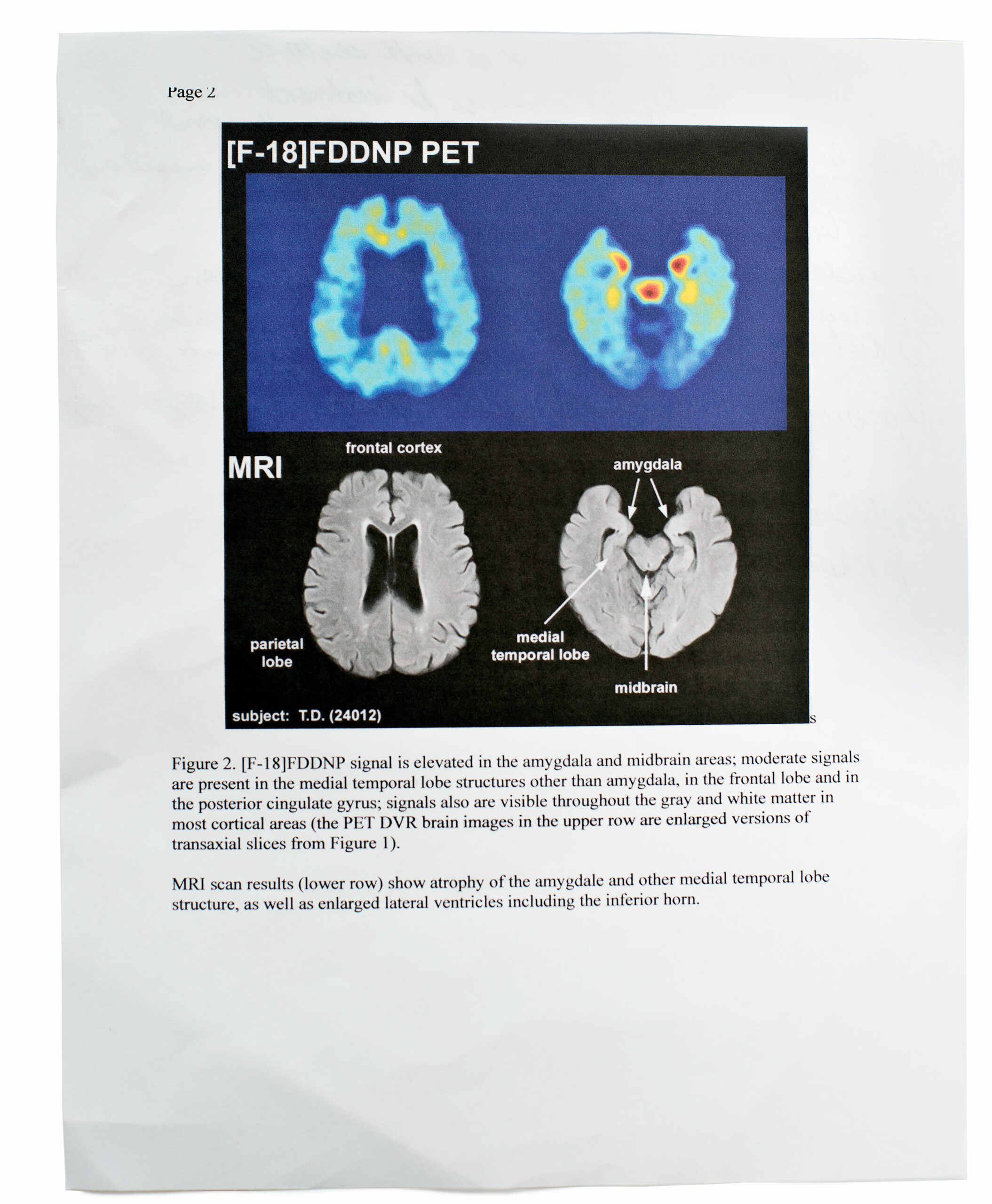

Last year, over a period of three months, a research team at UCLA put Dorsett and three other former NFL players through a battery of tests and brain scans. In November, they released their findings: the four players were diagnosed with signs of chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, a degenerative brain condition. Some researchers have linked CTE—which they believe is caused by repeated head trauma—to dementia and depression. Although the work at UCLA is encouraging to the medical community, and to former players like Dorsett, there is still no definitive test to determine the presence of CTE in the brains of the living—only postmortem.

That’s why former players such as Junior Seau and Dave Duerson shot themselves in their hearts. They hoped someone would figure out what had happened to their brains. That’s why Dorsett and others are so excited by the research coming out of UCLA. Maybe they won’t have to make the same choice that Seau and Duerson did. Maybe, if doctors can determine the presence of CTE while they are still alive, they can find a cure.

Apart from being one of the first living players to be told he may have CTE, Dorsett is the most famous former athlete connected to the condition. For the next few days, after the results of his testing were released, his story was everywhere. Hill is hopeful that Dorsett’s fame will keep it there.

[img-credit align=”alignnone” id=” 861571″ width=”1200″]

[/img-credit]

[/img-credit]“Dorsett is a leader. He always has been,” Hill says. “It’s unfortunate that he’s experiencing these things, but I think he brought awareness.”

Dorsett is glad just to finally know.

“Well, I was very much relieved that I was diagnosed with something,” he says. “It was a relief to find out what it was, what was happening with me. But disappointment with that, too, obviously. But, but, but—now I know. Now I know what I gotta do.”

✮

It’s on the tip of his tongue. “Um, shit.” He rubs his hands together, trying to find it. “Getting all the, um, what do I want to call it? Not vitamin E. Not vitamin E, but for my brain—” He rubs his hands together again. He gets up and walks to the kitchen. “See, that’s what it is,” he says over his shoulder. “That’s what it does to you. Makes you forget. Can’t remember from two seconds ago.” He opens a cabinet near the refrigerator, under the sign that says “When the queen is happy there is peace in the kingdom.” “DHA. DHA. That’s for my brain. Fish oil. A lot of that fish oil, man. A lot of nuts. A lot of natural stuff. It helps with getting the brain back.”

Dorsett’s plan of attack on his symptoms so far, mostly of his own design, has been natural. Herbs and vitamins, even seasonings on his food.

“I’m a real stickler about medicines, and what I put into my body,” he says. “Some people might not think so, because I might drink every now and then”—he laughs—“but the thing is, when it comes to medicine, man, I’m really careful. Because my liver and kidneys and all that, I don’t want them to start malfunctioning, because of taking too much of some type of medicine, and that could very easily happen.”

There is no formal treatment for CTE at the moment, because there is no formal clinical diagnosis, says Dr. Munro Cullum, director of neuropsychology at UT Southwestern Medical Center. He’s not one of Dorsett’s doctors, but he did collaborate with researchers from the UT Dallas Center for BrainHealth on a study released in 2013 examining the neuropsychological status and brain imaging of 34 former NFL players, including former Cowboys fullback Daryl Johnston. “It does not appear in any diagnostic manual,” Cullum says. “It is not a billable code to insurance.”

Cullum says a variant of CTE was first discovered in the 1920s in boxers; it was named dementia pugilistica or, more simply, punch-drunk syndrome. CTE refers, more or less, to the same phenomenon: a pathological brain state thought to be due to repetitive brain trauma. Its symptoms include cognitive impairment and changes in mood and behavior. A patient with CTE has an accumulation of the protein tau in a particular pattern. Doctors have found this pattern in the autopsied brains of Seau, Duerson, and more than 50 other former NFL players. Tau is also found in the brains of patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

That’s what researchers know for sure about CTE. They don’t know when tau builds up, or if it continues to accumulate past a certain point. They don’t know if the buildup can be reversed. They don’t even know, with absolute certainty, what causes CTE—if anyone with a history of concussions will eventually get it or if some people are genetically predisposed to it. There was only one thing Cullum and his fellow researchers learned for sure during their study of former NFL players.

“I have talked to many of them, and I have never met anyone so far that has said they wouldn’t do it over again,” he says. “I have not met a one. Even guys that retired young, after a concussion, they still—to a man—say I would do the same thing over again.”

Cullum calls the findings in the UCLA study Dorsett participated in “encouraging, but they are extremely preliminary.” In his own study, he found the rate of dementia in former players was “no greater than you’d expect in a sample of people over the age of 60,” but the “incidence of depression and mild cognitive impairment was higher than you’d see in the general population.”

“We really need to get large-scale studies of these guys,” he says. “We’ve got to get college players involved. We’ve got to get detailed histories of concussions, and then do imaging and follow them over time, see what happens.”

Cullum is careful with his words when talking about Dorsett, as he would be with anyone who had received the diagnosis the UCLA doctors gave him. He is a researcher in the field, so his words carry extra weight. There is too much unknown at this point to use them lightly.

So maybe medical science is unprepared to say that Dorsett has CTE. Maybe doctors won’t know for sure until they have his brain under a microscope. But do you want to tell him he doesn’t have it, or that two decades on a football field didn’t cause it? That no one knows why he started yelling at his daughter out of the blue, or why he can’t remember on a Wednesday that the Cowboys played the Chicago Bears on a Monday? Do you need to? Maybe if you’re handling his insurance claims. Maybe if you want to believe that a sport as violent as football doesn’t exact a cost.

Otherwise, what does it matter? The UCLA diagnosis gave Tony Dorsett something that doesn’t come as easy to him as it used to: an answer.

✮

Do you remember? Tony Dorsett does.

In that Monday night game against the Minnesota Vikings, Tom Rafferty’s and Herb Scott’s blocks bought Dorsett 10 yards. After that, it was up to him.

He outran two Vikings and shrugged off two more, breaking through their arms as he moved diagonally across the field, continuing to his right. At the 20-yard line, he cut up the field again, running on the yard markers.

“Look out, he’s got great speed!” Frank Gifford yelped on the Monday Night Football broadcast.

“Ah, nah, 99 yards and a half,” former Cowboys quarterback Don Meredith followed. He already knew where this was going.

“It was like, make the guy miss, make another guy miss, and now we’re going down the sideline,” Dorsett says from his chair in Frisco, smiling inwardly, staring into the middle distance, seeing those moves.

By midfield, that’s where Dorsett was, the ball in his right hand just like his coaches told him, keeping it out of reach of any Vikings. There were only two left that had a chance—cornerback Willie Teal, who had sprinted from the other side of the field, and strong safety Tom Hannon.

Teal and Hannon were slightly ahead of Dorsett, trying to find an angle to cut him off. But wide receiver Drew Pearson was in their way. As they crossed midfield, Pearson dove forward, trying to block Teal—he missed, but took out Hannon anyway.

There was one man left to beat.

✮

The youngest of Myrtle and Wes Dorsett’s five boys was known as Anthony until he arrived at the University of Pittsburgh in 1973 and the athletic department persuaded him to go by Tony, giving him those perfect, marketable initials: TD.

When he was a junior at Pitt, his Panthers played a road game against the No. 1-ranked Oklahoma Sooners. In the second quarter of what turned into a lopsided loss, Dorsett was coming around the left end on an option play, trying to convert on fourth down. He had a blocker in front of him, but Sooners safety Scott Hill leaped over the Pitt fullback, flying almost four yards in the air. Hill was sideways when he collided with Dorsett head high.

“He hit me like a torpedo,” Dorsett says.

He staggered back a few steps, then dropped to the field ass first, then flat onto his back, his arms falling to the ground above his head. He says he remained conscious, but watching a clip of the collision and its aftermath makes that difficult to believe.

“When I went to the sideline, I said, ‘Coach, it’s gonna be a long day,’ ” Dorsett says. “I said, ‘They droppin’ ’em out of the sky now.’ ” He laughs and bends over to pull up his socks.

That was just one hit, relatively early in Dorsett’s football career. He didn’t even leave the game. How often did that happen? He ran for a then-record 6,082 yards in college, another 12,739 yards as a pro, which was second only to Walter Payton when Dorsett retired. Anyone can look that up. But who knows how many wrecking-ball shots he took during that time? Even if doctors can’t be certain Dorsett has CTE, should anyone be surprised he is having trouble remembering things?

His teammates aren’t. They don’t want to believe this is happening to their former teammate, but they aren’t surprised. Doug Cosbie played tight end for the Cowboys with Dorsett from 1979 to 1987. He was there. He knows what his teammate went through, what he played through. “I remember specifically a game in Philadelphia where he was knocked out in the first half and then played the whole second half, and ran for, like, 100 yards,” Cosbie says.

The Philadelphia game. Dorsett isn’t where he is now just because of the hit he took from safety Ray Ellis during that 1984 game, a helmet-to-helmet shot in the second quarter that knocked him out. It wasn’t a single hit that did this. It was a career full of those hits, sustained during a time when the rules were looser, the equipment was weaker, and age 59 was a long way off. But it’s the best example, the one he talks about, the one that has been played and replayed as B-roll footage during most of the stories about him. He has said it was “like a freight train hitting a Volkswagen,” and the image of Dorsett, helmet twisted around from the impact, hits just as hard 30 years later when placed in its new context. As Cosbie says, Dorsett stayed in that day, too, running for 99 yards in the second half.

He was going the wrong way on every play.

Dive 30 and Dive 31 were two of the Cowboys’ standard running plays—straightforward rushes up the middle, either to the right or left of the center, depending on the number called. But no matter which play came in from the sideline during the second half, Dorsett would take a step in the opposite direction before receiving the handoff from quarterback Danny White. He couldn’t keep it straight, and the Eagles couldn’t keep up.

“Philadelphia had never seen that, seen me take that counter step, so it was throwing them off,” Dorsett says. “And every time I went to the sideline, Coach Landry and them were like, ‘You’re not supposed to take the counter step.’ I’m like, ‘Okay, okay.’ But every time they called that play, I did a counter step—boom. I would get 15, 10, 20 yards a clip.”

Despite suffering a head injury—despite being knocked cold—Dorsett wasn’t held out of the Cowboys’ next game. Nothing changed. Except for one thing.

“That play—Counter 30, 31—became part of our arsenal,” Dorsett says. He laughs. “Yeah. I invented a new play for us.”

✮

Dorsett lasted longer in the NFL than he thought he would — a dozen years, the first 11 with the Cowboys. He finished his career with the Denver Broncos, retiring before the 1989 season. He briefly considered a comeback in 1990, but, for the most part, when he left the game, he was ready.

“When I came into the league, I said, ‘Man, if I’m out here four or five years, I’m gonna be the happiest football player on earth,’ ” he says. “So I doubled that and some change.”

Dorsett knew he didn’t have the temperament for coaching, the patience, but he thought he might make a good color commentator. Maybe he could call college or pro games. He had always been able to handle himself in front of a camera. The opportunity never presented itself. When Dorsett was done with football, football was done with him.

But he has never been able to replace it. His former teammates struggle with the same thing. “We even have a saying,” says Bob Breunig, who played middle linebacker for Dallas from 1975 to 1984. “ ‘You play 10 years for the Cowboys, and you spend the rest of your life getting over it.’ ”

They were America’s Team, though they hated the name and the target it drew on their backs. More important, they were Dallas’ Team, and when they were out on the town—at Le Jardin, at Elan, up and down Greenville Avenue—that was just fine.

“Let me tell you something, bro: let the good times roll, baby,” Dorsett says. “It was a lot of fun. It was a lot of fun from the standpoint of winning games, being with a lot of great players, but then, socially, it went through the ceiling, man. We had a lot of single guys on the team. We had a lot of fun.”

That’s not what he misses. That’s not what he hasn’t been able to replace. He is happy being a family man, just another suburban retiree, Janet’s husband, Jazmyn, Madison, and Mia’s dad. But he isn’t anyone’s teammate anymore. He misses being around a team, everyone fighting for the same goal, going into training camp and watching it all build from there, knowing that 50 guys have each other’s backs. And, yeah, he misses the rush that came with it, how he could be down for a week and then a big game would change everything. There are no more big games. “You don’t get those quick fixes sometimes here in the real world,” he says.

But it’s even more elemental than that.

“You know, football is me,” he says. “I mean, football is in my blood. If there was something I could do, I’d do it right now.”

He doesn’t blame the game for where he is now. Dorsett was a football player, and that’s what a football player does. Play with injury, play when it hurt, because it always hurt. He played with a broken transverse process bone in his back, “squealing like a pig” on every hit, so painful the other team was running to the Cowboys sideline begging the coaches to pull him from the game. He made those choices based on the information he was given, took those chances. “Giving it up for my team, for the NFL,” he says.

No, it’s not the game that let him down, he says. It’s the league that paid him to play it. He says the NFL knew the risks associated with concussions and brain trauma and kept it quiet, kept it from both the players and the public, treated those head injuries like just another sprain or tear, a temporary setback, not a potential lifelong problem. The league and its owners should have looked out for him and his fellow players, he says.

“I’m a Hall of Famer,” he says. “I’m one of the most visible guys during my era. And nobody’s reached out to me. Nobody from the NFL has even checked, even asked a question to me. ‘Hey, man, I’m sorry’ or ‘Hey, man, I wish you well’—whatever. ‘Man, is there anything we can do to help you?’ You know, because sometimes—I go to doctors and I can’t remember the doctors’ names.”

It’s difficult for him to go to the annual Pro Football Hall of Fame induction ceremony now. He hasn’t been in a couple of years. It should be a celebration of the past, but Dorsett only sees the future.

“I say, ‘Is that me? Is that gonna be me in three, four years, I don’t know, five years, 10 years—is that gonna be me?’ I’m on that path. I’m going down that road. It’s sad—it’s sad—to go to the Hall of Fame and see these great players that meant so much to this great game, being in the condition that they’re in, and they’ve got to fight and struggle and plead for help. That part is mind-boggling to me. Mind-boggling, man.”

✮

It’s mostly his short-term memory that fails Dorsett. But his long-term memories are starting to become more elusive, too.

“I’m sitting here trying to think where I was at yesterday,” Dorsett says. “I’m sitting here thinking, Man, where the hell was I at? Where was I at? I know I went to this basketball game with my wife. After we were doing our shopping, we went to a basketball game. I think it was the eighth-graders. I don’t know. We couldn’t stay but half the game. But I’m beating my mind up: Where did we go? Where did we go? I mean, man, I’m determined to figure this out, so I gotta go back and think—and then I can’t get it. And then if I keep thinking about it, then I get this fog. And I’m like, ohhh, man. Just beating myself up.”

Dorsett sinks deep into his big, brown leather chair, his head back, staring at the ceiling. On the ottoman in front of him, his phone buzzes with a text. He looks at it and tosses the phone back where it was, then leans over and pulls up his socks again. Charlie, the tiny, shivering dog at his feet, takes this movement as a sign that they’re going outside, so Dorsett gets up and lets him out into the backyard.

He’s seen a lot of Charlie lately. He hasn’t been doing much. He hasn’t wanted to. In a couple of days, he’ll get on another plane, this one bound for New York, to attend the Heisman Trophy ceremony. After that? “I’m in limbo right now,” he says.

He’s spent a good portion of his retirement being Tony Dorsett professionally, acting as a spokesman for this company or that, a sportswear company here, a long-distance provider there, showing up at meet-and-greets, attending banquets, maybe a car show, shaking hands, taking pictures. But he doesn’t do much of that anymore. He has thought about doing some motivational speaking, but he’s done it before and doesn’t really like it. Lately, he hasn’t felt like doing any kind of public speaking.

“I didn’t even want to do radio or TV, because I’d be doing an interview and all of a sudden I’d forget,” he says. Just like, ‘Oh, man—what were we talking about?’ It’s embarrassing, man. You want to go out and be productive and try to do things, positive things, and you get discouraged because of the fact you can’t remember people’s names, you don’t know where you’re going.”

He doesn’t know where he’s going right now either, but he knows he needs to go somewhere, stop hanging around the house so much. “My wife is gonna get tired of me.”

His phone buzzes again.

“I’ve got people calling me all the time,” Dorsett says. “I’ve got doctors, people want to help me pro bono. They’ve got this new technology, a new technique. So many doctors have offered help. I’m so appreciative. It makes me feel that when I was playing ball, I touched some lives. Not just myself—we gave entertainment to people, and they appreciated it so much that they want to give back, give something to me for all the enjoyment that we’ve given to them over the years. I get calls almost every week, and there’s a doctor that’s got this and a doctor that’s got that. I can’t use everybody’s treatment.” He laughs. “Something might start misfiring.”

✮

On that Monday night against the Minnesota Vikings, Dorsett wasn’t sure if he was going to make it.

“I actually thought I was gonna get pushed out of bounds,” he says. “I was tiring a little bit.”

Vikings cornerback Willie Teal had to slow down a step or two to avoid the pileup of Drew Pearson and Tom Hannon, but he finally caught up to Dorsett just before the 20-yard line. But he was tiring, too. He didn’t have enough. Dorsett stayed in bounds, on his feet, on his way to a record 99-yard rushing touchdown.

“Can you believe that?” Don Meredith asked the Monday Night Football audience, as Dorsett crossed the goal line near the right pylon. He rounded off the run near the back of the end zone, his arms outstretched, punctuating the play with a simple right-hand spike of the ball, a casual and almost perfunctory gesture. Pearson caught up to him in the end zone, engulfing Dorsett in a bear hug that pulled him up onto his toes.

“He didn’t have enough shove in his push, or push in his shove, to get me out of bounds. And it ended up a record-setting run.” He raises his voice. “One that you can’t take away from me! The only thing you can do with that one is tie it, man. You can’t break it. You can only tie it.”

Do you remember? Tony Dorsett does.

But for how long?

Write to [email protected].