Dallas at the time was known to have radical Islamists. It had served as the communications hub for the planning of the 1993 World Trade Center attack. One Dallas grocery clerk, Eyad Ismoil, was convicted of driving the explosives-bearing truck into the basement. His associates were still here. So was Wadih el Hage, a top Osama bin Laden lieutenant later convicted of U.S. embassy bombings in Africa. Also in Dallas, allegedly, were leaders of the terrorist group Hamas. American and Israeli intelligence investigated Islamic charities in Richardson believed to comprise the U.S. headquarters for Hamas. (One of the charities, the Holy Land Foundation, will go to trial in July.) Hezbollah sympathizers were here, too, running clandestine fundraisers in North and East Texas in the late 1990s.

To deal with the threat, the Dallas field office built the largest joint counter-terrorism task force in the country. When Gamal joined it, a deep distrust of the force had spread through the Muslim community. Gamal’s superiors found him a unique commodity. Because he was an observant Muslim and had lived for years in North Texas, he already had the number of every mosque and person of import in the Muslim community. And because of the years spent managing 7-Elevens, and the job he did there, the Muslim community held him in high esteem.

“He was honest before he worked for the FBI, and everybody knew about his honesty,” says Jamal Qaddura, a longtime activist at Gamal’s old mosque in Arlington. “And even after he came back as an FBI agent, I can promise you that everybody, including members of every mosque, approached him, talked to him, invited him to their homes. The comfort zone was there.”

Knowing this, the FBI gave Gamal a role it had given no other agent, past or present. Gamal’s mission was to circulate in his community, openly advertising himself as a member of the FBI, giving assurances that, as a fellow Muslim, he could be trusted to take information in confidence. The unprecedented role “was a no-brainer,” says Danny Defenbaugh, who headed the Dallas office from 1998 to 2002.

One of Gamal’s first orders of business was to set up a peacemaking meeting between FBI officials and Muslim leaders in 1998. The leaders were concerned that the bureau was investigating every mosque in North Texas, given the headlines coming out of the Holy Land Foundation in Richardson. Gamal brokered a deal in which both sides would meet in the back room of a Denny’s, because no mosque would hold a meeting with the FBI. Some 20 people attended, none of them imams.

“You’re just on a fishing expedition,” one Muslim said. “You guys have nothing on us.”

Defenbaugh responded that the FBI wasn’t investigating mosques. (But he didn’t say the bureau wasn’t investigating the people inside the mosques.) He spent much of the night explaining how the FBI worked, how it got arrest warrants and permission to order wiretaps and surveillance. He asked those in attendance only “to let us know when someone is breaking the law.”

Gamal never said a word. He stayed in a corner of the room. But the message was clear: if Muslims could trust Gamal to come to this meeting, then they could trust the FBI co-workers who spoke for him. Gamal arranged more meetings. Soon, imams attended, and the information began flowing to the Dallas field office. “He’d make the introductions, and our agents just ran on it on their own,” says Tino Perez, Gamal’s former supervisor on the international terrorism task force. “He helped a lot with stuff like that.”Every time, upon leaving the courtroom, Gamal would change his routine and double back, constantly checking for followers. The assasination threat revealed a vulnerability that would haunt Gamal from then on.

It wasn’t long before field offices across the country called on Gamal to confirm associations or make identifications for their own investigations. Word also spread among other cities’ Muslim populations: the Dallas agent could be trusted to relay information in confidence. “They would talk to him,” says Charlie Storey, a retired Dallas cop who for years worked on counter-terrorism cases with the FBI. “I can remember a lot of things that he did that no one else would have been able to accomplish.”

Gamal’s mission didn’t sit well with everyone. People involved with the Holy Land Foundation, for one, asked Muslim leaders to ban Gamal from the mosque in Richardson. Mohammad Suleman has been the mosque’s president for years. He recalls people saying, “Do you know an FBI agent is coming to the mosque? Do you know he’s spying on the mosque, profiling us, reporting our names and taking pictures?”

Some did more than just complain to the leadership of their mosques. Not long into Gamal’s new post, an FBI informant said a reputed Hamas activist in Chicago asked people in Dallas to take photos of Gamal and gather information on his new wife, Amal, whom Gamal met on a trip to Cairo in 1998, and Gamal’s relatives in Egypt. The plan was to assassinate the Muslim agent. The threat never materialized, but for the second time, Gamal’s work endangered more than his own life.

He believed the key to keeping his career and personal life in tact was transparency. He would not use the duplicitous measures sometimes employed by his covert FBI brethren. He would not order surveillance. He would not wear a wire. He was praying where he worked. He was working where he prayed. The distinction between public and private life had not only blurred, but was set up to blur.

•••

In May 1999, Gamal flew to FBI headquarters in Washington, D.C., to complete some training, and there he received a call from an old friend, Abbas Ibrahim. They’d known each other since they were students and roommates in New York during Gamal’s first visit in 1980. Ibrahim lived in Washington and worked as an accountant for BMI, an Islamic banking firm. The two got together whenever Gamal was in town. But this call was for business.

“Gamal, I think I’m in big trouble,” Ibrahim said. “We need to talk in private. Instead of a restaurant, do you mind coming out to the house?”

Over a home-cooked meal, Ibrahim said the FBI had just subpoenaed his boss, Soliman Biheiri. It wanted Biheiri to appear before a grand jury in Chicago. Ibrahim figured he was next, and he told Gamal what he knew. He handed over a piece of paper. On it were instructions from Biheiri to wire large sums of money to an Islamic charity suspected of funding Al Qaeda’s bombings of two U.S. embassies in Africa the previous year.

Ibrahim said he thought BMI helped pay for the bombings. But Ibrahim didn’t want to get in trouble. “I want the FBI to know I’m coming forward to help. I’m not part of anything.” He said Biheiri was cracking under the strain of the investigation and could be persuaded to meet with Gamal because he was a fellow Muslim.

Gamal didn’t say anything, but he recognized the investigation as a piece of an international case code-named “Vulgar Betrayal.” The Chicago office was handling it. Chicago believed a wealthy Saudi businessman named Yassin Qadi had been secretly controlling U.S. companies, including BMI, and laundering money for Osama bin Laden’s terrorism operations.

When Gamal returned to Dallas, he paged Chicago Special Agent Robert Wright Jr. Wright and his partner, Special Agent John Vincent, had been working the Qadi investigation for a long time and at great government expense. They were thrilled when Gamal phoned. Even better, Biheiri got a message to Gamal asking for a meeting. Plans were made between Chicago and Dallas to exploit it.

In a conference call between Chicago and Dallas, attended by six agents and supervisors, and years later recalled by many of those present, Gamal was asked to meet Biheiri wearing a wire. Gamal objected. Flustered by the accusatory tone of the questioning, he tried to explain but his words came out convoluted. Something about how he was involved in a delicate assignment in Dallas, one that would be jeopardized if he wore a wire. The Chicago agents brushed that aside. All they seemed to hear during the back-and-forth was Gamal saying, “A Muslim does not record another Muslim.” Gamal recalls something slightly different. He says he told the Chicago agents that if he recorded another Muslim, it would be tantamount to religious betrayal in his community. “Because in their opinion, a Muslim isn’t going to record another Muslim,” Gamal recalls saying.

Danny Defenbaugh, Gamal’s Dallas boss, understood his reservations. Defenbaugh consulted with others familiar with Gamal’s assignment, then spoke with Bill Eubanks, the acting head of the Chicago office. Defenbaugh says Dallas and Chicago agreed that Gamal shouldn’t wear a wire. Still, the Chicago agents, Wright and Vincent, sure of what they’d heard, pressed ahead with formal complaints against Gamal, accusing him of dereliction of duty and possible disloyalty. They demanded an internal investigation. The complaints ultimately went nowhere, and “Vulgar Betrayal” was abandoned.

This seemingly did no harm to Gamal’s career, which was on the rise. He had already investigated Wadih El Hage, the lieutenant of Osama bin Laden who lived for a time in Arlington and was involved in the 1998 embassy bombings in Kenya and Tanzania. (El Hage was later convicted and sentenced to life without parole.) In December 2000, Gamal took a post in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, as a deputy legal attaché. It was one of the bureau’s most prestigious posts. Gamal would be the FBI’s ambassador to Saudi Arabia. But he had no time to enjoy the promotion. FBI Director Freeh handpicked Gamal for an assignment investigating the USS Cole bombing that had occurred a couple months earlier. In October, off the coast of Yemen, two Al Qaeda suicide bombers drove an explosives-laden boat into the Cole, killing 17 American sailors and wounding 39 more. In December, the Yemeni intelligence service took a man into custody named Jamal al-Badawi. Freeh wanted Gamal to fly over and interview him.

Over the course of five days, Gamal and another agent extracted a confession from al-Badawi, as well as the names of seven conspirators. Gamal did it by striking at al-Badawi’s Muslim pride, reducing the man to tears by questioning al-Badawi’s beard, a symbol of Islamic piety. Gamal says he told al-Badawi, “I used to respect people with beards, who will never lie even if their lives depended on it. But now, because of you, I will never respect beards.” The information eventually led to the capture and imprisonment of 13 conspirators.

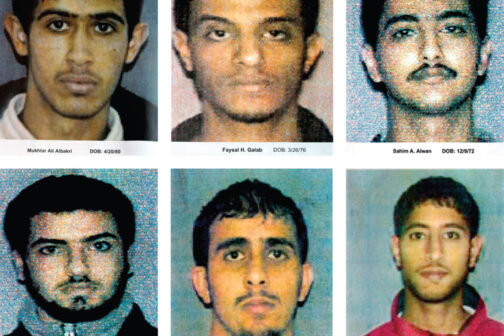

Back in Riyadh on September 11, 2001, Gamal found himself at the epicenter of the War on Terror. Fifteen of the 19 hijackers were Saudi. The work Gamal did is classified, and Gamal declines to discuss it. But in early 2002, an urgent call came for him. A 21-year-old U.S. citizen from Lackawanna, New York, by the name of Mukhtar al-Bakri, had been captured by Bahraini authorities. Gamal was ordered to repeat his performance in the USS Cole case.

The Buffalo, New York, field office had developed a tip that six Americans in the area had formed a terror cell after receiving training at a bin Laden camp in Afghanistan. But the bureau didn’t know their names or much about them. They suspected al-Bakri, but Pete Ahearn, the former head of the Buffalo office, says, “We didn’t have anything at the time to pin on these guys. We needed someone to cooperate.”

Gamal found al-Bakri frightened by the Bahraini security cell. Gamal played the role of the friendly American rescuer, his sole purpose to help a fellow citizen, and Muslim, in trouble. Before long, “The kid was looking up to Gamal as a father figure,” Ahearn says. “He wasn’t hard on him but was authoritative. Gamal said, ‘Look, if you don’t work with me here you’ve got a problem. You might not be going back to Buffalo. You’ll be going to Guantanamo as an enemy combatant.’” After a few hours, Gamal had a signed statement from al-Bakri, which was then used to roll five more plotters. The Lackawanna Six, as they were later called, were indicted and convicted on terrorism charges. President Bush eventually touted the case as the biggest domestic success in the new War on Terror.

Six months later, in November 2002, Gamal’s career came tumbling down.

•••

After 9-11, the nation rushed to identify FBI failures. Agents in Arizona, Minnesota, and elsewhere came forward with stories of bureaucratic ineptitude leading up to the attack. Special agents Wright and Vincent of the Chicago office offered their own stories. After all, Yassin Qadi, the wealthy Saudi businessman viewed to be secretly controlling BMI, was linked to financing 9-11. Wright and Vincent broke ranks and told the Wall Street Journal in 2002 that Gamal had refused to record another Muslim—because Muslims didn’t do that—and the bureau had not only protected Gamal but promoted him to one of the most sensitive posts in the War on Terror. Soon after, ABC News’ Primetime aired an interview with Wright and Vincent. The piece implied “Vulgar Betrayal” might have foiled 9-11 were it not for the disloyal Dallas agent who had said, “A Muslim does not record another Muslim.”

“It was right out of his mouth. Five of us—no—six of us heard it!” Wright told Primetime. “I was floored! I went back upstairs, and I called FBI headquarters to tell them what happened. And the supervisor said, ‘Well you have to understand where he’s coming from, Bob.’ I said, ‘No, no, no. I understand where I’m coming from. We both took the same damned oath to defend this country against enemies both foreign and domestic, and he just said, “No”? No. Hell no.’”

The story buzzed through the Internet and mainstream media well into 2003. Gamal was a traitor. Gamal was a mole. Gamal should be deported. The FBI didn’t handle the story well. It wouldn’t let Gamal explain himself because of the bureau’s protocol against agents discussing classified information. It did release a statement to media outlets detailing Gamal’s unique mission in 1999. It also held background meetings with reporters on the allegations made by agents Vincent and Wright. But all of this received little play. The story was too sensational to be nuanced to death. “It was a shark frenzy,” Danny Defenbaugh says. “They [media outlets] decided to just go ahead and trash him.”