MICHE WALSH, A WISPY, GREEN-EYED GIRL whose dyed white hair rises straight from her head, has already spent two hours in her bedroom at her parents’ North Dallas home, trying to decide what to wear. Her closet is stuffed with a combination of funky, real thrift-shop trash and expensive nouveau clothes designed to look like trash. Finally, she picks a black miniskirt, black leggings, a black, shiny sweater and a long, metallic, striped coat. Miché adds a couple of pink and green streaks to her hair and slips on a new pair of oddly shaped copper-and-snakeskin shoes, bought earlier that day on her mother’s charge card.

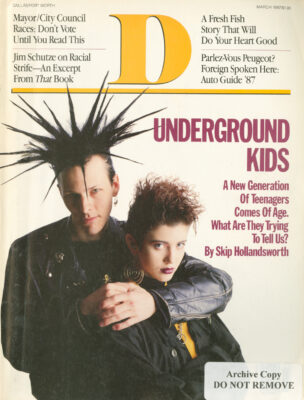

Miché who’s at that stage where she no longer looks like a child but isn’t quite yet a woman, stares at herself in the mirror one last time and wonders if she is making enough of a statement. Statements have always been important to Miché, a petite teenager with a high, excited voice, skin so white it seems made of cotton, and shining, dark eyes that can flutter in a second from a mischievous gaze to the weary look of a woman at least ten years older. For Miché, as with most of the Deep Ellum regulars, the right image is a frame for her entire personality. Lately, she has been trying hard to develop what she calls an “underground glamour look.”

“The things you’ve got to do,” she says with a sigh, her voice trailing off, “to be different . . .”

By the time Miché makes her appearance on the streets of Deep Ellum, the nightly carnival of the new youth counterculture is already in high gear. As usual, it is a reeling, Felliniesque portrait, utterly baffling to those who are not a part of it. A torturously loud band called Rigor Mortis, playing in the pitch-dark Theatre Gallery on Commerce Street, launches into a song called “Die in Pain” (“Killed your first man at the age of thirteen; Life’s lessons taught you to be cool and mean”). The lead singer sticks out his tongue and tries to roll his eyes into the back of his head. A hundred kids push forward to the stage, many tossing their heads back and forth as fast as possible in an act called “headbanging,” while a dozen others, off to the side, begin throwing themselves into one another. They bounce away, only to be slammed by a body coming from another direction. One boy falls and is trampled by several pairs of shoes. He leaps up and almost joyfully hurls himself back into the other slammers.

Standing on the street outside the club is a gang of skinheads, teenagers who imitate the right-wing British toughs of the Sixties by shaving their heads and showing more than a casual fondness for violence. The word is out that they’re feuding with another skinhead (action in town. Last week, one of their members was attacked and beaten in Deep Ellum. “Chaos is about to go down,” says one of the leaders, who calls himself Andy Anthrax.

Across the street at the less-frantic Prophet Bar, more young people gather. Another band is playing with that typically obscure, discordant sound blared out by most new music groups, the lyrics emphasizing nuclear war and hopelessness. Meanwhile, everyone is laughing and having a good time, as if they sense no contradiction between the raging nihilism of the music they’re listening to and the fun they are having.

At the door of the bar, collecting the cover charge from patrons, is a thin nineteen-year-old boy named Chris Kile. He ran away from home last year and lived for a while in a sleeping bag in an abandoned Deep Ellum warehouse. On first impression, with his short hair and hard stare, he looks tough. Look again, and he is just another teenager searching for something he doesn’t quite understand. “If I wasn’t down here on the streets experiencing the aggression,” says Chris, who wants to be an artist, “then I’d feel like an important part of the world would be passing me by.”

This scene of noise, aggression, and vanity is Miché’s universe. She has been on the downtown scene for six years, ever since she was a thirteen-year-old punk hanging out at a dank bar called Studio D. Everyone then knew her as the frail little girl squealing through the club, completely messed up on acid. Now, whether others like her, or whether they hate her (as some do) because she has lost her old hard-core look and is starting to look too New Wave chic and ritzy, they cannot help but notice her,

Miché sees one of her many friends, a skateboard punk named David Adrians, known around Deep Ellum as David Dude. Skateboard punks are the carefree, urban equivalent of California surfers or beach boys, They spend most of their time zipping up and down the streets on their skateboards, acting oblivious to anything else. “You’re on the streets, you’re down low. you’re part of the city,” says David, who’s nineteen. He started skateboarding as a kid because no one would give him a ride anywhere. Now, his favorite thing about cars is the huge parking garages, which make great skateboard ramps at night when they’re empty. He wears old jeans with a hole in them and a T-shirt. The toe of his right tennis shoe that he uses to stop his skateboard is wrapped with duct tape.

“David Dude,” Miché yells, though she didn’t need to say anything. David has already seen her.

“What’s happening tonight?” asks Miché”.

David Dude shrugs. Around him, circulating among the Deep Ellum clubs or just hanging out on the streets, are more young people-a few hard-core punks wearing Mohawks, some other skateboard punks, the death rocker punks wearing their black bondage clothes and their chains, runaways, young painters who have always wanted a bohemian scene, graffiti aficionados who like to spray-paint walls, the “trendies” who want to be a part of What’s Happening, artsy people who like to dress in wild costumes, even a few preppies who feel a vague need to do something different with themselves. In all of the clubs are enthusiastic young rock bands, working themselves and their audiences into a frenzy.

David Dude takes a look around him at the theatrical nighttime show, here among the chic rubble of the warehouse district just east of downtown. Then he looks back at Miché.

“Nothing’s going on,” he says with a sigh. “Nothing at all.”

NOTHING IS GOING ON? ALTHOUGH VERY few Dallas adults seem to have given it much attention, out of the nether world of Eighties teenage life has come a post-punk, counterculture movement of sorts, one that at first glance seems to have no real political message or social consciousness but is nevertheless jampacked with energy. While this movement has attracted greater publicity in cities like New York and Los Angeles, in Dallas it has been largely ignored, because until recently no one knew where to find it. The little underground scene, mostly centered in new-music nightclubs, was so ephemeral that by the time mainstream Dallas had heard of one of these clubs, it had already shut down and another had opened somewhere else.

But a lot of kids like Miché Walsh have known exactly what was happening. She began sneaking into the downtown punk bars in 1980, when she was a high school freshman, wearing, like everyone else, black leather clothes, spiked chains, crosses, pins, and buckles. She cut her hair into a Mohawk and dyed it white and black. These were the nascent days of the Dallas teenage underground, when some kids began to dress like fashion outlaws and listen to a new kind of music to find some outlet for their rebelliousness. To adults, Miché was a mere child who seemed poised on the edge of self-destruction. Her father, an executive with a national motorcycle manufacturer, and her mother, who runs a modeling and talent agency, hoped it was a phase that would pass.

It didn’t. For Miché, and soon for hundreds of kids just like her, the harsh, aggressive nightclub scene downtown gave her life a connection-although exactly to what, she could not say. She would listen to records by groups like the Circle Jerks, the Buzzcocks, and Christian Death, bands whose sounds sometimes seemed more like aural anarchy than music. The music’s primitive energy, however, touched a part of Miché, and she found herself returning almost every night to clubs like Studio D and the Twilite Room downtown. She got her news about the new bands through fanzines or through an occasional modern music show on the radio.

“I wasn’t trying to upset my parents or anything,” Miché recalls. “It was just fun for me because there was this new way to rebel.” She used to spray-paint “Shit on You” on the walls of the punk clubs. She began doing a lot of drugs and sometimes showed up drunk at school. “I went around trying to look like a tough-ass, memorizing the words to all the hard-core songs because I knew it would offend people. 1 wanted to show that I didn’t have to do anything other people told me to.”

“There were some kids into this new music-punk trend, but there was no one like Miché,” says Jo Jones, the director of art at Arts Magnet High School where Miché graduated. “She came to school one time wearing this skintight black bondage outfit with zippers that were opened all the way-exposing her sides. She wore all these chains and spikes. She was thirteen years old. This was her way of belonging. I kept thinking, ’What is happening here?’”

But more disaffected kids became attracted to this scene-rich kids, runaways, kids who hated their parents, kids who thought their parents were cool, kids who felt a deep anger, kids who just wanted to be part of a fad. They were the legacies of the punk scene that had begun in the late Seventies (see page 89). when coarse rock groups who seemed more violent than musical played a tuneless, grating rock music, the lyrics reflecting the degrading life of the industrial cities of the Northeastern United States and urban England. Though most of the Eighties kids stopped dressing in the severe mold of the earlier punk movement, there was still that deliberate stylistic belligerence and exaggerated, anti-fashion look, almost all of it patterned after the underground rock music (called “hard core” by music writers) that they were listening to.

“What no one had guessed was that a bunch of kids were hungry to pick up on something that was designed to shock everyone back into reality,” says Jeff Liles, twenty-four, a local booking agent who began picking up on the new hard-core movement when he was a Richardson high school student, Now he is one of the most influential people in the underground music scene, booking many of the young bands that play the clubs. ’The music might not have been sophisticated,” says Liles, “but it did speak to a lot of us kids who began to realize how stupid the normal music was on the radio-you know, all that Seventies supergroup bullshit. Suddenly, here was this sound that sort of captured all the typical teenage alienation, What you heard in that music was your own frustration.”

With almost no publicity from the media, radio, or record companies, this movement slowly caught on-the same way the rock culture in the late Sixties emerged. The Eighties generation became followers of groups like Bauhaus, Siouxsie and the Banshees, and The Cure. The music also spurred kids to start garage bands of their own, with that same aggressive sound and all with offensive names. The most wonderful irony of the new era? The son of Mr. Peppermint, the man who hosts the popular children’s show on WFAA-TV, helped form a band called the-sorry- Butthole Surfers, which has now become one of the most well-known hard-core music groups in the country.

From the outside, it all looked and sounded the same-raw, painful stuff that didn’t make much sense. Many parents dismissed the teenagers as a clique that surely would fade away. Few thought that the ranks of these new, hard-edged kids would continue to increase.

“But if there’s one thing I’ve learned,” says Miché’s mother, a thoughtful, pretty woman, “and it’s been a hard lesson, it’s that when kids say they aren’t understood, they’re usually right. There have been a lot of parents who don’t want to really come to grips with the tact that their children are going through a new scene. They don’t pick up the signals. And soon they are worlds apart, and no one can figure out why.”

Two years ago, when the avant-garde nightclub movement started expanding through Deep Ellum, which had consisted mostly of abandoned warehouses and a few artists’ lofts and galleries, the underground fringe emerged. And it came in a hurry. Some young people in their early twenties, who had never really been satisfied with the rather sterile Dallas nightclub scene, found an outlet for their frustrations. Isolated teenagers who had spent a lot of time alone in their bedrooms, listening to their records and watching the modern music groups on MTV, suddenly had a place where they could meet others just like themselves. Even if they couldn’t get inside the clubs, they could at least walk the streets and talk to one another.

Says Russell Hobbs, whose Theatre Gallery (a combination art gallery-new music nightclub) was one of the first big Deep Ellum hangouts, “I think what was most amazing is how many young people there were in Dallas that wanted to be part of a new scene. There were hundreds. Some North Dallas people would come down here and go, ’Where the hell did all these kids come from?’ And I’d say, ’What do you mean? They’re your kids.””

Finally, many parents are convinced that another generation gap is appearing, setting off these singularly styled kids even from people in their late twenties. They don’t understand the music or the clothes or the attitudes. And they are bewildered that for many of the young crowd, including Miché Walsh, this lifestyle has become not just an adolescent ritual, a phase, but a seminal factor that may determine the way they shape their lives. “There’s a tougher edge to this new group of kids.” says Mark Ridlen, twenty-seven, who played in the early punk rock bands in Dallas and now is a Deep Ellum video artist. “They’ve already been through so much by the age of fifteen-drugs, sex, all the usual things-that nothing impresses them anymore. Sometimes I think it’s scary.”

Throughout her teenage years, Miché has been, in one phase or another-from kid punk to the girlfriend of a street-tough skinhead-a vivid part of the new youth scene. As it has with many of her friends, the underground life has nearly pushed her over the edge. She has gone through a bout of alcoholism, a lengthy drug addiction, even a suicide attempt. Still, she is lured back to Deep Ellum nearly every night.

“Let’s face it,” says Miché, who changed her name a couple of years ago from Lisa Michelle to sound more original. “None of us knows what we’re really doing. We’re all just trying to find ourselves before it’s too late.”

THE WEEKEND STREET TRAFFIC IS GETTING HEAVIER. Despite the cold wind whipping around the old buildings, the kids stay on the streets. Near the Video Bar, the high-tech little club on Commerce that plays music videos from the new groups, Miché” flits past a cute girl her age who is saved from being an All-Amer-ican beauty by the (act that one eye has been deliberately blackened with mascara.

Other, well-known Deep Ellum kids are nearby. There’s Reeta Franklin, the tall blonde-haired girl who lets kids stay at her little rent house on Ross Avenue. She calls it “Reeta’s Youth Hostel and Cantina.” Recently, one rich teenage girl showed up there and within three days had dyed her hair black and thrown away all her old, preppy clothes.

There’s Matthew Bailey, who fashions his dark hair into eighteen six-inch spikes that stick straight out from his head-a style initially designed to infuriate his parents, and now meant, he says, “to scare people.” In reality. Bailey is about as harmless as a stick of chewing gum, but when you first meet him, you think you are looking at an atom bomb.

If there is one threatening group on the Deep Ellum streets, it is the skinheads, who are hanging out this evening in the parking lot up from Theatre Gallery. They wear Doc Marten’s combat boots and camouflage jackets, under which they carry cans of beer. Several of them have nightsticks or knives hidden up their sleeves. Like the original skinheads from England, most of the thirty or so Dallas skins, ranging in age from fourteen to twenty-one, come from working-class families and adhere to the right-wing rhetoric of their British role models. “I believe in my country and my race,” says Gecco, one of the leaders. “And no one is going to stop me from believing that.”

There are even very young skinhead girls. One of them. Cherry, a tiny thirteen-year-old who looks like a waif from a Dickens novel, comes to Deep Ellum from Garland whenever she can get a ride. Cherry says her mother, who is divorced, doesn’t mind if she stays out all night. “I hang out with the skins because I feel protected” she says.

“Shaving all our hair off was the ultimate rebellion,” says fifteen-year-old Aaron, a new skinhead. Ironically, their nearly bald heads (they let their hair grow out a little in the winter) give them an even more innocent look. All of them look like little Boy Scouts, except for Gecco and Andy Anthrax, the two older leaders. Andy has knife wounds all over his back. Gecco cannot remember the number of fights he’s been in. “They’re definitely aware,” says Jeff Liles, the Deep Ellum music promoter, “that they’re acting like Nazis. The doorman of Club Dada was standing outside one night and watched them all attack a guy and slash his legs with a knife. It freaks me out because I’ve seen the Dallas cops come up and frisk them and then let them go, which just encourages them more.” But the skinheads argue they have been given a bad rap and that the cops are picking on them unfairly. “These other punks you see around here, they’re geeks,” says Andy Anthrax. “We hate them. Like all those transvestite faggots you see at Club Clearview? We don’t care for that. And we don’t like drunk ropers, either. But that doesn’t mean we try to beat them up. We like to stay to ourselves. Now I’m not saying we don’t occasionally thomp [a skinhead word for fighting]. If a guy messes with us that we don’t think is worthy, then we’ll kick the shit out of him.”

Recently, the skinheads split into camps with the breakup of the local skinhead band called N.O.Y.B. A couple of the members left to join another band called White Legion, formed by Ken Seaton, a twenty-nine-year-old skinhead who had just come to town. Feelings have been harsh ever since. Seaton claims that Andy and Gec-co’s group attacked one of his friends, Andy and Gecco’s group blames Seaton’s group for attacking one of their members, Malachi.

“They cracked my damn head wide open,1’ says Malachi, who obviously has some kind of weapon underneath his camouflage coat.

Although the group by Theatre Gallery doesn’t know it, Seaton and one of his skinhead cohorts, Phil, are over at Club Clearview that very night, standing in the lobby to stay warm. “All we want to do,” says Phil, “is get drunk and hang out. The other skinheads are trying to cause a public war.”

“One way or other,” says Ken Seaton, who wears glasses and has the big, friendly face of a man you usually see in church, “someone is going to get it.”

Actually, very few people here give the skinheads much thought. “Oh, don’t worry about them,” says Miché. “They’re not out looking for trouble. They just want an image.” And in truth, the skinheads seem rather boring compared to other Deep Ellum regulars like Susan Senyard, the most prominent “death rocker” in Dallas. She’s a pale, fierce-looking young woman who is always draped in black and adorned with loads of chains and Gothic crosses.

The dozen or so death rockers in Deep Ellum try to stay out of the sun in order to maintain a pallid, corpse-like complexion. They dye their hair pitch-black and listen to music by groups like Sex Gang Children or Christian Death whose eerie lyrics focus, as Susan explains, “on the joy and release of being dead.” Not that she wants to die-she just likes the concept. Plus, the music is good.

Susan, now in her early twenties, was hospitalized from the sixth to eleventh grade, unable to walk, because of a spinal tumor. She says the new, hard-core music gave her an energy that helped get her out of the bed. To her, the new lifestyle is like a salvation. But it hasn’t been easy: she still moves with a limp. A couple of weeks ago, haunted by the fact that she still could not dance or walk like everyone else, Susan went home to her apartment and cut her legs with an X-Acto knife. She began to freak out. Trying to call a doctor, she called a number for take-out pizza. “I didn’t know what I was doing,” she says, “so I ordered a pizza.”

Now, with the hard gaze of a soldier, she stares out at the crowds. Many of the young people wear ordinary clothes; others deliberately dress down in torn blue jeans or psychedelic tie-dyed shirts or tight miniskirts with ripped fishnet hose. There are those who look like they have been body-dipped in makeup, and others who show up in extravagant get-ups worn only because the avant-garde magazines claim this is now the hottest fashion. They all pass from one club to another. It’s really not hard to get into these clubs if you’re underage; no one looks closely at the doctored IDs, if they look at all.

“I know it’s now trendy to come down here and go to underground bars,” Susan says somewhat angrily, “but just remember something about those of us who have been here a while. We’ve gone through all the stages. We’ve tried to be normal. We went through a stage where we sat at home and tried to gross out our parents. We’ve gone through it all. Now we’re saying, ’Hey, this is it. This is the way we are.’”

Miché” agrees completely. “In some ways, everything I’ve learned is down here,” she says in her bubbly style, her sentences always punctuated with “Oh my God” and, the buzzword of the new generation, “Coo-oool.”

“I can remember when the Misfits came to play,” Miché says. “They were such a cool hard-core band. I was down here, doing my ’to-hell-with-the-world’ act, trying to piss off as many people as I could. So, I was sitting on the edge of the stage, and the bass player tried to kick me off. Well, oh my God! I couldn’t believe it. So I shot him the finger. That really got him mad, so he tried to hit me with his bass. I fell off the stage, but then I got right back on again. And I wouldn’t move. It was, like, so cool! I had power that I never knew I had before.”

Nevertheless, Miché” has begun to wonder over the last couple of months if her Deep Ellum evenings have begun to change. It is something she can’t exactly put her finger on, but she sometimes ponders whether the new youth revolution she once felt so much a part of has, at least for her, lost a little of its sting. Her teenage days are nearly over, and though she does not say it to her friends, she wonders what will happen next.

MICHE HEADS TO CLUB CLEARVIEW, HER favorite Deep Ellum nightspot, which has lost its lease and will be shut down after the weekend. She knows that the weird, graffiti-filled nightclub with a little something for everyone-psychedelic black-light rooms, a recorded-music dance room, another huge room for live acts, dark hallways connecting all the rooms together-will reopen two blocks away in a couple of months, but Miché” is worried that it will never be the same.

She loves this place. Although a lot of Deep Ellum purists hate Clearview because it is too commercial {Theatre Gallery owner Russell Hobbs calls it “Club Queerview”), no club in Dallas has brought together so many different groups of people, punks and preppies and everything in between, Club Clearview has become a repository for bizarre acts-from incomprehensible fashion shows that end with a woman model pretending to cut off the genitals of a male model, to odd performances by crazy local rock bands like Joe Christ and the Healing Faith, in which lead singer Joe Christ, trying to show that rock music is like a religion, serves “communion” to the audience in the middle of his act.

Club Clearview has an “artist in residence,” Clay Austin, who spray-paints pictures and slogans on the walls. He also creates what he calls “environments” to enhance the patrons’ experience at Clear-view. He turned a corner of the club into a bum’s flophouse, complete with an old tattered sofa and dirty wash basin, and on Halloween, as part of his haunted house, he rounded up some dirty-looking street people, gave them each a bottle of wine, and had them sit in a dark passage upstairs to scare those who walked by. There was a “vintage car” party, where people were instructed to enjoy themselves while standing around four old cars; toward the end of the night, a man and woman impulsively decided to have sex together in each car. When the famous nightclub columnist Stephen Saban of Details magazine in New York came to review the club, he was dazzled, especially when he found the little shower area in the women’s bathroom where two people had just been caught trying to make love.

For many, this is what the underground has become, a nightclub where flamboyant art and decadent living are thrown together in acombustible mix. Hundreds of pressed-together bodies dance madly until 4 a.m. in a building that, depending on your frame of reference, is either aesthetically pleasing or looks as if vandals have just attacked it. There is no question that Clearview is a wild place-’you get to do things and meet the people your mother always warned you about,” says Miche”-and it has been too great a temptation for some. Several who have worked there had to quit because they became addicted to drugs. “One manager after another has headed off to drug rehabilitation centers,” says artist Clay Austin. “People party with such intensity, as if it’s the last night of their lives.”

Miché” used to work the door here, an underage teenager herself, checking others’ IDs. It was one of the glamour jobs of Deep Ellum. “Everyone knew me. They all had to get past me to get in the club. I became somebody other than just another face.” But she, too, had to quit after a few weeks; she was doing so much cocaine each night that she could not sleep. She felt she was losing control of her body.

It was not the first time that the wild life had come close to ruining her. After she graduated from high school in 1985 and moved into her own apartment for the first time, she found herself getting more and more depressed-she says she is not entirely sure why. “The only thing I had going for me was my nightlife,” Miché” recalls. “At night, it seemed like I was somebody. And even then, I didn’t know what that meant.”

The depression grew worse. Miché” started drinking throughout the day, and at night, she’d go to all the clubs. One night she got drunk, did drugs, and tried to slit her wrists. She says she doesn’t even remember doing it. A neighbor had to break down the bathroom door to reach her. Afterwards, Miché” stayed in a psychiatric wing of Presbyterian Hospital for four months.

But even while in the hospital, Miché had her mother bring up all her funky clothes. She even dyed her hair again. “It’s not that you don’t worry as a parent,” says Barbara Walsh. “But, you know, no matter how hard a parent tries to keep his or her child away from it all, there’s got to be times when you realize nothing can be done. The more you try to prevent something from happening, the worse you can make it.”

A few weeks after Miché left the hospital, she returned to the Deep Ellum scene. “I’m sure,” says Miché, “that my parents went, ’Oh, my God. She’s back.’ But what could I do? I loved the way I felt there. I began to go back to my old places, like the Theatre Gallery and the Video Bar. I hung out with the skinheads and the skateboard punks. I tried to get to know everybody. I kept thinking the old underground lifestyle was freedom. No one could tell me what I could or could not be.”

“There have been so many girls like Miché,” says Jeff Liles, “who come out of the suburbs or privileged North Dallas, turn a little bit wild, and then they come down here and lose it.”

NOW. MICHE WALSH IS DETERMINED NOT to lose it again. A few months ago she moved back home with her parents. She started taking classes at a local junior college, concentrating again on her painting, as she did back in high school. Recently she went back to her old high school for the opening of an exhibit of paintings by recent graduates. Miché” had submitted a disturbing self-portrait. In the painting, the right side of her face looks normal, but the colors begin to distort on the left side of her face, giving the painting a nightmarish quality. “It’s me going into transitions,” Miché says. “It’s like when 1 look at myself in the mirror, I see part of myself sliding away, sort of like a snake sliding out of its skin.”

Miché’ also says she has quit using drugs. When she recently heard that her best friend from high school, Margaret Gwynne, had nearly died from an overdose of speed, Miché knew that it could just as easily have been herself. She calls Margaret often. Margaret, now twenty years old. is recuperating at her parents’ home in Oak Cliff. She talks in a halting voice, and when she is asked what she would have done differently, she says, “Nothing. I know it almost killed me. But it was everything I wanted to say and do and be. It was a moment in my life I had to have.”

Miché nods her head-there is a dangerous thrill to the teenage underground life that you can’t get anywhere else-but she says there has to be a way of living it and still being normal. “Like reconciling your nightlife with your real life, you know?” she asks.

Indeed, most of her old underground friends are changing. As Miché” comes into Club Clearview for its last big weekend bash, her old high school boyfriend, Chad Evans, the former drummer for a well-known teenage hard-core band called Man in the Reign, is a few streets away, performing eclectic, improvisational music with a guitarist-“performance art,” he calls it-at an art gallery opening. The gallery patrons stare at the paintings while Chad, playing a variety of percussion instruments, tries to “capture the mood.”

The music is soft and perplexing. In his punk days, Chad used to blast away on his drums to songs like, “If Only I Had a Brain,” “Dying Eggs,11 and one of the crowd’s favorites, “F- You.” He and Miché were known as the teen lovers of the punky hardcore scene. They gave each other gifts like spiked dog collars to wear around the neck; once Miché gave him a bracelet made of tabs from beer cans. At the end of Chad’s senior year in high school, they broke up in the parking lot of one of the punk clubs. “It was heartbreaking,” Miché says. “We knew we had to do something else with our lives.”

“There was something about the obscure-ness of that hard-core, underground life that was so appealing,” recalls Chad, a bright young man who also is a serious painter. “But a lot of us were all trying to be new and different without taking the time to understand what that meant.”

Still, hundreds more are following the same path. As Miché glides into Club Clear-view, several young teenagers sit in the lobby, staring at her. One, Heather Cohlmia, fifteen, is a beautiful, dark-haired girl, wearing black leather and loads of dark mascara around her eyes. She sneaks out of her house on weekends (“my parents have no idea I do this stuff”) and just sits in the lobby or stands out on the streets. “The doormen won’t let me in,” she says, “but it’s worth the wait.”

Over at Theatre Gallery, more kids, including some new ones who have never heard this kind of music before, come in to slam-dance to the music of the hard-core band. Rigor Mortis. The band, whose music is really skull-shattering, plays a song called “Foaming at the Mouth” (“It’s looking sick on the streets. Slobber drips. Bad disease from hell on my lips”). It’s like a riot. Two teenagers almost come to blows. One of the skateboard punks, Chris Jennings, who is sixteen and living on his own, bloodies his hand when he’s thrown too hard against the stage. He is thrilled. He holds his bloodied hand up like a badge of honor. “It’s all worth it,” he says. “Believe me.”

Another of the new Deep Ellum kids, Zaphod Weatherhod, fifteen, comes stumbling out of the Theatre Gallery holding his arm. He fell during the slam-dancing and someone stepped on it. He thinks it’s broken. Standing around his friends, Zaphod is trying not to cry.

“Dudes,” he says, “this is fun for me. I don’t care how bad off my arm is. My mom says it’s to take out my aggression, but I think it’s just fun.” A couple of guys, still sweating from the dancing, tell Zaphod they’ll take him to the hospital.

The boy looks at them, then he shakes his head. For a moment, all the toughness slips away. “No. dudes,” Zaphod says. “Take me home. I’ll get my mom to take me.”

MICHE WALSH RETURNS TO CLUB CLEAR-view again on Sunday, the final night before it is closed. Just about everyone is out. A floorful of dancers resembles fresh laundry tumbling in a dryer. Other hip people stand off to the side with cigarettes, their smoke all but obscuring one another from view.

All of Miché’s friends come up to say hello. There’s Izachaar, another former doorman of the club, who now wants to be known as the black Andy Warhol; he’s start-ing his own Deep Ellum newsletter to chronicle the exploits of his generation. A couple of members from the Daylights, a hot Deep Ellum band, come in; so does Miché’s Highland Park friend, Emily, who has just begun a drug rehabilitation program; and Reeta Franklin, wearing something that looks like an Indian turban, surveying the crowd and calling them all “bohemian Eurotrash”; and the underground theater director Brooks Tuttle, maybe the wildest Deep Ellum dresser of them all. Tonight he is in something like a blue spacesuit and part of his hair looks like it was stolen from Elvis Presley, while the other part looks stolen from Wayne Newton.

One guy after another approaches Miché. She does have a peculiar radiance, and her eyes glitter when she laughs. Miché flirts with them all, then moves on. A trio of young women, all Club Clearview regulars, stare harshly at Miché. “She’s not a part of this anymore,” says one of the girls. Another says, “She doesn’t represent what Deep Ellum is about,”

That may be true. Miché plans to begin working part-time at Klub Sprx, a slick, new-music club across town. She likes one of the DJs there (“God, he’s to die for”). She wants to start living a more glamorous lifestyle, “and so maybe I have passed this stage,” she says. “All right, people think I’m selling out, but I just don’t have the same feelings. And, like, the old way for me might be disappearing, but at least I lived it. I’ll always think of it as a dream.”

Toward the end of the night, Miché” begins walking through the club. She’s looking at all the graffiti, trying to find all the things she had written on the wall. When she gets to the girl’s bathroom, she takes a little breath and says, “Oh, my God.” On the wall, in gold, is a crude, spray-painted picture of herself. Beneath it are the words, “Miché’- A Legend in Her Own Time.”

“Oh, my God,” Miché says again.

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Football

The Cowboys Picked a Good Time to Get Back to Shrewd Moves

Day 1 of the NFL Draft contained three decisions that push Dallas forward for the first time all offseason.

Arts & Entertainment

DIFF Documentary City of Hate Reframes JFK’s Assassination Alongside Modern Dallas

Documentarian Quin Mathews revisited the topic in the wake of a number of tragedies that shared North Texas as their center.

By Austin Zook