It’s a Sunday afternoon in late March, the Mavericks’ season is spiraling, and Luka Doncic is at war with his father.

The battlefield? Dominos, played over mobile phones across the Atlantic, often before Mavericks games as a discreet way to ease the pressure before the 24-year-old takes the court.

“I have to admit Luka is better, but not by much,” Sasa Doncic says. He chuckles when asked about who referees their online matches. “No refs—that’s why it’s good we play online.”

We are in the Ljubljana studios of Arena Sport, a regional television sports network, and Sasa has just plopped down on the couch in the office of Luka Stucin, Arena Sport’s chief editor. In less than an hour, Dallas will take on the going-nowhere Charlotte Hornets in a game the Mavericks will disastrously lose, one of many moments that doomed a campaign that began with so much hope to an awful ending. I’ll be doing commentary for that one. Meanwhile, in a different studio, Sasa is on the call for the Adriatic League derby between local club Olimpija Ljubljana and regional force Partizan Belgrade.

Even at 49 years old, you can’t miss the fact that Sasa is an ex-basketball player. At 6-foot-7, he stands every inch as tall as his son, with the same wide shoulders and thick build that, just like Luka, makes him more imposing in person. His white hair gives away his age, but his attire—always rocking Luka’s Jordan Brand training gear plus the signature shoes to match—and his perpetual smile and jokes make you feel like you’re with one of your high-school buddies every time you talk to him.

And if you’re out to dinner with him?

“Food and funny anecdotes will be coming non-stop for four hours,” Stucin says. “He’s like your grandma who makes sure that everybody is stuffed.”

For more than 40 years, basketball has been Sasa’s life. His 18-year professional playing career gave way to more than 10 years and counting coaching and running basketball operations for a smaller local club, alongside his more recent gig in broadcasting.

But outside of Slovenia, Sasa Doncic is known best for his famous son. And as Luka Doncic continues to climb the ranks of the NBA’s greatest stars, his father’s influence only becomes more obvious in Dallas.

Fast forward to early June, when the focus in Dallas shifted to the upcoming NBA Draft and free agency after the Mavericks finished in 11th place in the Western Conference. By then, the centerpiece of the franchise was long gone to the other side of the world. Luka Doncic had been in Slovenia since May, working to refine his game and body. Sasa is participating in both transformations, the latest chapter in a shared hoops journey that’s shaped Luka’s life.

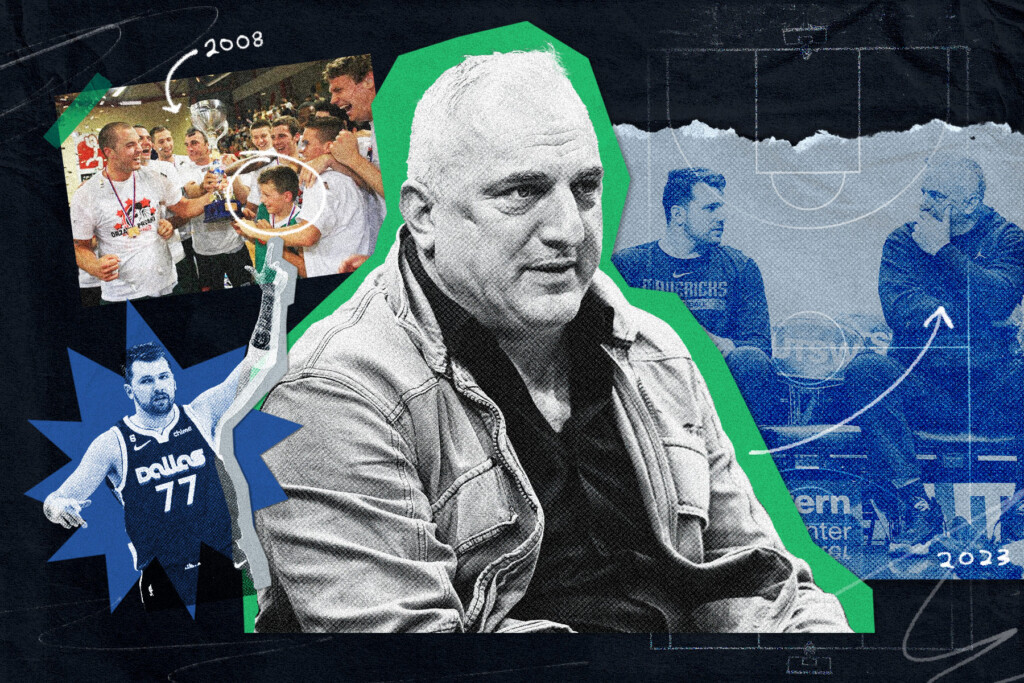

One of the first milestones came 16 years ago, when Sasa was winning the second of back-to-back Slovenian titles—the first as a member of Helios leading the upset over the always-favored Olimpija Ljubljana in 2007, then playing for Olimpija and beating Helios the following season after switching sides. Those titles rank among the highlights of Sasa’s career, alongside the EuroLeague run he spent with his protégé, future NBA star Goran Dragic, and another Slovenian legend tied to the Mavericks, Marko Milic, in 2007-08.

And watching his every move up close from the sidelines was 9-year-old Luka.

So much of what we see in Luka Doncic now, Dragic and Milic saw in Sasa more than a decade and a half ago. The ballhandling. The vision. The three-point range. The versatility to guard larger players while initiating his own team’s offense. Perhaps most of all, the unusually large frame all that skill was packed into. “Back in the day, his dad pretty much could do everything,” Dragic said last year.

Milic, now a player development coach for the Mavericks, went even further when we talked about Sasa, claiming that he had the same talent as Luka. If that assessment feels hyperbolic—the elder Doncic didn’t enjoy nearly the same career as his son—what isn’t is that Sasa Doncic was an example of where the game was going, a forebearer of positionless basketball.

“Maybe he wasn’t completely understood back then,” Milic adds. “He was ahead of his time. He was a player archetype that everybody wants now.”

Luka Bassin, Sasa’s ex-teammate and currently an assistant coach for the Slovenian national team, pointed to one other commonality: that both father and son are way more athletic than they look.

“Cameras lie sometimes,” Sasa says with a laugh in response, before adding a note that sounds picked from his son’s game: ”The most important thing in basketball is the first step. Quick, long step. End speed doesn’t matter that much, it’s the first step and change of pace when you get your opponent off balance.”

But the similarities go beyond the physical traits and basketball skills. Father and son share the same joy and cockiness with which they approached the game of basketball. “He always had a smile on his face. And he was fearless,” Milic describes Sasa. “He never had any limits in his head, like Luka doesn’t. He had the same childlike approach to the game that everything is possible.”

The fearlessness you see when Doncic goes against the biggest NBA stars and under the brightest lights is not accidental. Per Milic, Sasa was teaching his son adult tricks, preparing him to go against bigger and stronger competition ever since he was a young boy.

“Sasa brought Luka to my basketball camp when he was 9 or 10 years old,” Milic says. “When he brought him there, I told him that the camp is for 14- and 15-year-olds. But Sasa replied he’ll have to manage and figure it out. The five-year difference was huge, but Sasa never treated Luka with kid gloves.

“He never had it easy for him. And I think this made Luka what he is today.”

Perhaps that’s why, almost 15 years later, after Luka ascended to heights his father could only dream of, he’s still working out with Sasa. The setting is the Tivoli Hall, sacred ground for Slovenian basketball fanatics. Tivoli Hall is the venue that hosted the 1970 FIBA World Cup. It’s where Yugoslavia (which Slovenia was a part of at the time) won its first gold medal and where the biggest Slovenian club basketball success happened back in the ’90s. Now it’s where the country’s greatest player chooses to grind away when he’s home.

About an hour before one of their sessions together, I’m sipping coffee with Sasa in a small bar in front of the arena. I can’t help but ask whose idea this was. “It was all Luka,” Sasa replies. “The first or second day when he came from Dallas, Luka said to book the arena.”

Sasa says they’ve trained together in previous offseasons, but never as intensely as this one. If there’s any silver lining to the Mavericks’ dispiriting season, it’s that it afforded Doncic much more time for rest than usual, which in turn allows Sasa to crank up the intensity in their training sessions.

But you can’t train everything. Sasa laughs when asked about those “adult tricks” Milic referenced, but then lapses into thought. Finally, he highlights something that was apparent from the very beginning. “His decision-making is phenomenal,” Sasa says of his son. “In one-hundredth of a second, he’ll find 10 solutions. This is something that you’re born with.”

But it is difficult to imagine what it’s like to train a special talent like Luka Doncic as a child, much less now that he’s a global superstar. Luka spends his mornings with Slovenian national team strength coach Anze Macek working on his body. Sasa handles the afternoon sessions, which he characterizes as “a lot of shooting, a lot of skills training.”

“Whatever exercise I plan, if Luka does it, it looks like a great drill,” Sasa adds with another laugh. “Luka makes anything we do great. Then another player might try it, and it doesn’t look as great so you start wondering if it was that good to begin with. But Luka was always like that. Whatever you did, you didn’t have to show him 10 or 20 times. He would make it on his first try. He’s a very perceptive person. ”

He’s also notoriously competitive, something he inherited from Sasa. Nowadays, competition is a fundamental part of his dynamic with his son—and, no, Luka Doncic isn’t interested in letting his father win, either.

“Be it dominoes, chess, tennis,” Sasa says. “Not when we shoot free throws. I say, ‘Let me win, I haven’t played basketball in ages.’ But he won’t, because he hates losing and this is what makes him different. … He’s a natural-born winner. He wants to win in everything.”

Every coach I’ve met who has worked with Doncic tells me Luka needs to compete to stay engaged. Sasa, wisely, has incorporated that into their workouts. “We make small games, small bets,” he explains—anything from push-ups to bringing the other coffee. “Like, if he can make 50 threes on 60 shots, he wins. If not, I win. But it’s mostly me who has been losing all summer.”

It’s the byproduct of more than two decades of a teacher understanding his star pupil, a dynamic Sasa is adamant is the only one they maintain in the gym.

“Before practice, we can drink coffee and be father-son,” he says. “But once we enter the gym, it’s player-coach.”

“And once we’re done it can be father-son again.”

Only a few minutes remain before the workout is scheduled to begin when a black Brabus 800 SUV with 77 on its plates parks nearby. Out steps Luka—Jordan slides on feet, black backpack, and black slim/tight-fitting Jordan brand hoodie worn over training jersey and shorts. Ready for action. But no sooner does he plop down at the table than his phone comes out. Just like on the basketball court, however, little goes by without him registering it. When Sasa introduces me, jokingly, as a Slovenian journalist doing a story about him in English, Luka surprises me with a quick “I know that” acknowledgment. Later, when Sasa admits to Milic he was late to coffee because he forgot to pick up his daughter—after divorcing Luka’s mother, Mirijam Poterbin, Sasa remarried and has a 6-year-old daughter named Tijana—Luka jumps in to tease him about his parental skills. It’s the repartee of a father and son who are now peers as much as blood: a Balkan sensibility cultivated by Sasa and now passed down to Luka.

“He kept his sense of humor even during tough stretches of his life,” Milic says of Sasa. “And his sense of humor is special. When you are willing to laugh at your own expense, everybody around you looks at you differently.”

Fast forward two months, and the Slovenian national team is playing an exhibition game against Greece at the Stozice Arena in Ljubljana. It’s Luka Doncic’s first game after nearly four months off, and the sold-out arena is buzzing two hours before game time, a byproduct of Slovenians arriving early to make the most out of a rare opportunity to see their hero play in person.

Sasa meets me at the VIP entrance, and it doesn’t take much for him to gregariously convince the security guard to let me join him inside despite not having a proper ticket. Every single person in the arena knows who he is and wants a piece of him, too. He looks noticeably leaner; his son isn’t the only one who has shed pounds this summer.

“This happens when you go from five sandwiches for dinner to none,” he quips to an acquaintance who stops him to point out the obvious change in physique. “Now I feel like I’m eating dinner with a spoon that has a hole in it,” Sasa adds with a laugh.

Later on, when I asked him about the weight loss, Sasa admits it was prompted by a bet with an old friend from Belgrade. “But the subject of the bet is not important—it’s who you bet against,” Sasa clarifies. “Now I can trash talk that opponent for the rest of my life.”

Sasa knows how special the national team is to his son. “Since Istanbul [when Slovenia won the EuroBasket title in 2017], these guys are connected like a family,” he says. But there’s plenty of meaning for him, too. Professionally, that 2017 EuroBasket was Sasa’s coming-out party as the color commentator on the biggest commercial television channel broadcasting the tournament. It was when Sasa Zagorac, a member of the championship team, tore Sasa Doncic’s shirt open after the Finals win with Slovenia watching—and, yes, that involved another bet. That, and Sasa rallying Slovenians to come to the Finals in Istanbul by whatever means necessary—by ship, truck, car, and even paraglider—remain some of the most iconic sports broadcasting moments in the country’s history. So while Sasa didn’t call any games at this year’s FIBA World Cup, he is enough of a fixture not to feel the slightest bit out of place spending three weeks being around the team from Spain to Japan to the final rounds in the Philippines.

But the personal stakes are even bigger—especially tonight.

“Whenever I can see my child play live, it’s special,” he says. “But it’s even more special to see him play in the city where he was born and when you see the whole arena cheering, paying tribute. It’s a special kind of acknowledgment and honor.”

It is also recompense. Basketball pulled them apart for so many of Luka’s formative years. Now basketball is a way for father and son to reconnect now that Luka has reached adulthood.

“Look, Luka went away from home to Spain when he was very young, and you can’t bring those lost moments back,” he says. “From Madrid, he went to Dallas, so you don’t get to see your child every day or even every week. So as a parent, you appreciate these moments even more. So any moment I can spend with him—literally everywhere I can—means the world to me.”

The scene from two months prior flashes in my mind: Luka working out with Sasa in the gym, them sipping coffee beforehand, sharing laughs and cracking jokes the way a normal father and non-prodigy son. Like they might have during those teenage years or might now were they not separated by 5,500 miles nine months out of the year. Maybe they talk about these things. Maybe they don’t. But the hours in the gym—and Sasa’s presence in these arenas when Doncic takes the floor in his home country’s uniform—carry substantial unspoken weight.

“Sometimes, on court, you don’t have to speak much,” Milic says. “It’s enough they know you’re there for them.”

Sasa sees the man his son is becoming, and admires him. “Being in public with cameras everywhere, I don’t know if I could do it like he does,” he says. “The fact that you have to be paying attention 24/7, where you are, who you are with, what you do—man, that is not easy to process. Watching up close how he handles everything, knowing he doesn’t have a second of time when he is not disturbed, is unbelievable. Based on all the things that happened to him so far in his career, Luka stayed very real. Very grounded.”

Perhaps most of all, Luka Doncic has stayed joyful. It bursts out of him when he’s on the floor: the smiles, the smack talk, the gallery of unrestrained facial expressions. This, perhaps more than anything else, is Sasa’s doing.

“I think his approach, fearlessness, sense of humor—Sasa probably unintentionally instilled in Luka when he was young,” Milic says.

That still gets the best of him at times, like during Slovenia’s elimination at the hands of Canada in the quarterfinal round of this summer’s FIBA World Cup. Doncic, as he so often has, got embroiled with the officials, which led to an ejection. His teammates crumbled without him. After the game, the 24-year-old admitted he struggles with emotional self-control on the court.

His father isn’t phased by it.

“It’s a normal process. He’ll be more mature as years pass. He’ll start to look at some things differently.” Sasa says, before issuing a very Sasa Doncic correction. “But I don’t know when we completely grow up. I’m 49 years old, and I don’t know if I have completely matured. I’m still sometimes acting childish, like to joke and laugh.

“I want to stay like this for as long as I can.”

Author