Sara Mokuria was younger than her son is now when her father died. She tells everyone she was 10 because it’s simpler that way, but she was actually a couple of months shy of double digits. Just a 9-year-old little girl, with blood splattered on her pajamas and her father lying on the floor in front of her, dying from bullets fired by two Dallas cops.

It’s almost three decades later, and her son, Amari, is 10, for real, no rounding up, and what has changed since then? It’s not nothing. As a co-founder of Mothers Against Police Brutality, she has helped make sure of that. But it’s not enough. The brutal truth is, all these years later, what happened to Tesfaie Mokuria could still happen to his grandson Amari, whose middle name is Tesfaye. It could happen to Amari’s father. It could happen to Sara, and it almost has. She has looked down the barrel of a gun.

It’s not just the police. That’s the part that has gotten the most attention lately. Twenty-eight years gone and it remains such an inhospitable world for Black and Brown people. So she keeps fighting. She’ll keep fighting for a future that doesn’t need her to.

But she can’t help but look at the past and wonder how much they have all lost. Not just people. Possibilities.

“Toni Morrison says, ‘The function, the very serious function of racism, is distraction. It keeps you from doing your work,’ ” Sara tells me. “It keeps you explaining over and over again your reason for being. Somebody says you have no language and you spend 20 years proving that you do. Somebody says your head isn’t shaped properly, so you have scientists working on the fact that it is. Somebody says that you have no art, so you dredge that up. None of this is necessary. There will always be one more thing.

“And that, to me, is the great tragedy of my life. That I have wasted so much of my brilliance on this bullshit. I have wasted all of this energy. What could I create? What could we collectively create if this were not here to distract us? Five years fighting to remove Confederate monuments is beneath me.

“So that is the anger, that is the fire that lives within me, that my life, my brilliance—and not only mine, but that of so many. I am so lucky to know so many brilliant folks in this city and in this country and in this world. And so many of them, we’re wasting our energy fighting this. Our lives are built around fighting things.”

Sara laughs when I ask if she remembers the first time she protested, because it’s a bit like asking if she remembers her first breath. She is always there. If you’ve been to just about any major demonstration in this city in the past decade or so, you’ve no doubt seen her. The 37-year-old Dallas native is small in stature but commands attention, a head full of spiraling curls above slightly hooded eyes, always appearing as though she is taking measure of something. You have likely seen those eyes peering from above a mask as calls to defund the police grew louder over the summer.

She laughs when I ask the question because when was she not protesting? “First time I ever protested?” Sara says. “Oh, man. Probably coming out of the womb. Crying, ‘I want to stay in!’ ”

It’s a joke, but just barely, because even as a child she found cause for dissent. Her grandfather—her mom’s dad—expected children to be seen but not heard, and there was no way that Sara was going to accept that. “I could never get on board with You don’t have the right to say something,” she says. “That was just never—that’s not part of my constitution.”

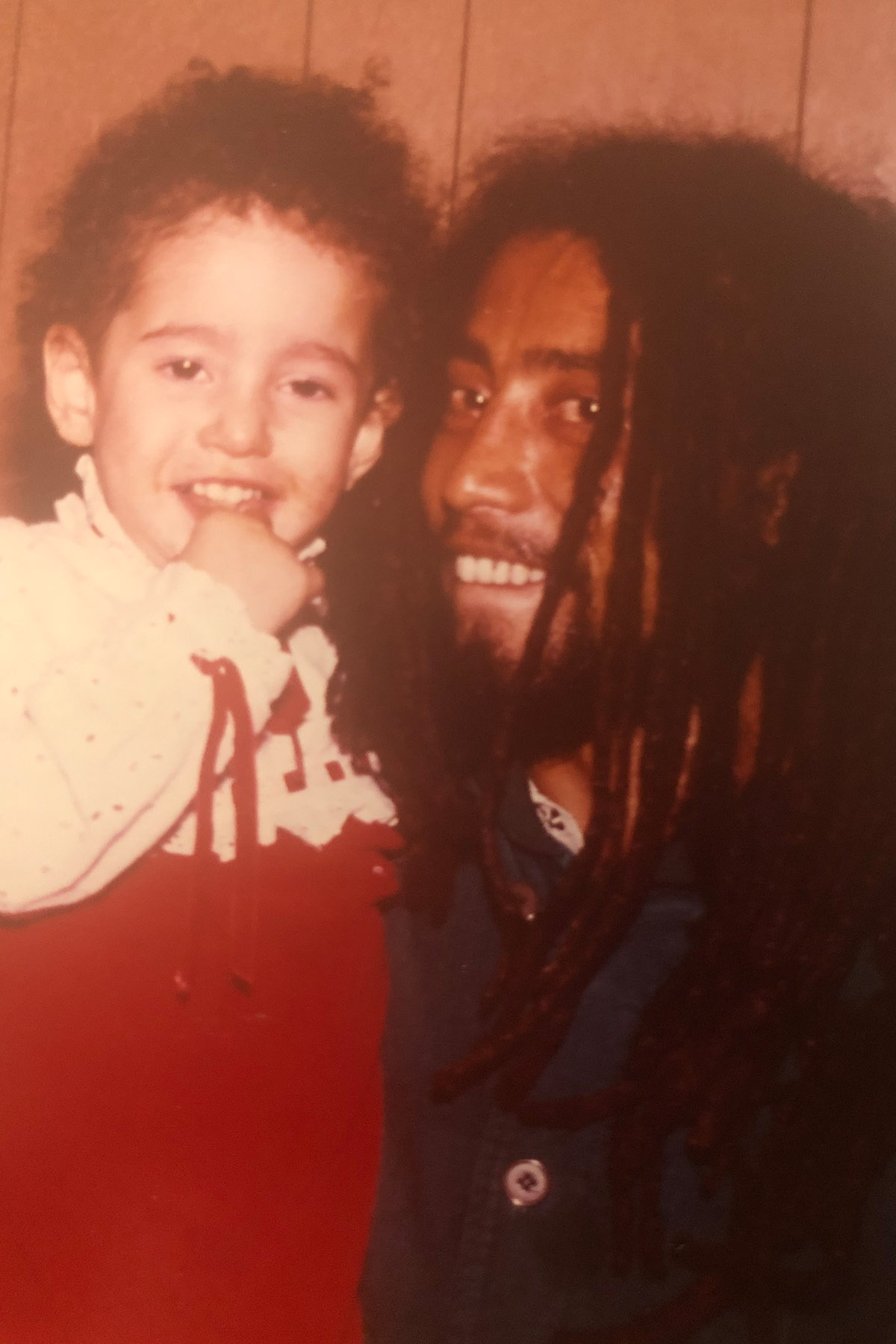

On the maternal side of her family, her mere existence was more or less an act of defiance. Her mother, Vicki, was Eastern European, and Tesfaie was Black, a political refugee from Ethiopia. Sara’s grandparents “were not accepting of my mom’s life choices in general,” she says. “They were accepting of me but not our family. I had very early introductions to race in America without a framework of understanding.”

Those introductions went beyond race and they went beyond her grandparents, too, touching on differences in religion and socioeconomics. Her family, she says, was working poor, and theirs was a Buddhist household on the buckle of the Bible Belt. When Sara was born, her parents lived in a fourplex on Oram Street, off Lower Greenville, and she grew up in East Dallas and Pleasant Grove. Tesfaie ran a landscaping business, and many of his clients were in Highland Park and North Dallas. Sara could see the gap between how her father’s customers lived and how she and her family did, even if she couldn’t quite make all the connections yet. Her father’s death only underlined those differences. “It really wasn’t until I was a young adult that I was like, ‘Oh, everything makes sense now.’ ”

That, to me, is the great tragedy of my life. That I have wasted so much of my brilliance on this bullshit. I have wasted all of this energy. What could I create?

But she had already been fighting. As a theater student at Booker T. Washington High School for the Performing and Visual Arts, Sara and her friends would even hell-no-we-won’t-go school assemblies. “We weren’t really protesting anything. It was just oppositional to authority,” she says. “There’s this recognition of rules and norms that didn’t see me, didn’t understand me.”

Part of her opposition found its fuel in the unresolved rage stemming from her father’s death. She was working through it without exactly knowing how to: she simultaneously hid from the world around her, disappearing into giant clothing, and lashed out at it. But Sara was also arguing for her place in it. She brings up a line by the late poet June Jordan: “Wrong is not my name.” “That feels like the mantra of my life. It was like everything about me from the outside forces was saying, ‘You’re wrong. You don’t belong.’ ”

There was an idea there, a mission statement, that Sara would get to later: If the world sees me as wrong in so many ways, I have to make a world that sees me as right.

“I think that without a clear pathway of what that meant,” she says, “that was marinated in me.”

Aileen Mokuria likes to say her older sister “bumps into history,” and she means things like this: two weeks after Sara arrived in New York to attend The New School, 9/11 happened.

“I watched the second tower fall,” Sara says. “So here I am, 19 years old, at the center of geopolitics.”

Her dorm room was across the street from Union Square, the closest public space to Ground Zero. When the resulting war broke out, Union Square became the beating heart of the peace movement, and Sara fell into its rhythm. This is where she started to create a world that would see her as right. Becoming part of the anti-war contingent led her to the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement, which taught her about fighting police brutality.

“And at this point, I’m still internalizing my childhood and my story and not recognizing those things as paths toward advocacy,” she says. “I’m just there. I have a politic that’s unrefined, but it’s being cultivated by the experiences of my life.”

Her professors at The New School played their part, too, exposing her to texts that helped her make sense of the world in which she had been living. More than that, one of her professors also pointed Sara toward the Institute for the Recruitment of Teachers. She decided she was going to be the kind of high school history teacher who would show her students how the world really worked. That would be her “concrete methodology of social change,” she says.

She went to Simmons College in Boston to get her master’s degree (she ended up getting two). She would also get an education in being an organizer, mostly through the case of Hector Rivas, a bus mechanic whose accidental death on the job in the spring of 2006 had been erroneously ruled a suicide by his employer. In New York, she had only been a participant, going to rallies and protests but not yet understanding “the role those things played in a larger campaign,” she says. “I wasn’t at that table.”

But Sara came back to Dallas still with the intention that the way she was going to effect change would be as a teacher. In 2008, she was at Skyline High School, just a couple of miles from where she grew up in Pleasant Grove. She wrote her own curriculum for a cluster then called Man and His Environment, mixing sociology, political science, law.

Early into her first year, though, Dallas ISD ran into a budget crisis, after a miscalculation left the district facing a $64 million deficit. Almost 400 teachers were let go. Sara remembers seeing kindergartners crying on the news as their teachers were laid off. She did what she had been trained to do, and began organizing parents and teachers to protest Michael Hinojosa (then in his first tenure as DISD superintendent) and the school board. That’s how she met John Fullinwider, then a fellow teacher in the district and an activist in Dallas going back to the late 1970s. Fullinwider had started a superintendent’s resignation vigil in front of the old administration building on Ross Avenue, showing up every Thursday for months. He says Sara was “the coolest person [he’d] met in 10 years.”

“Some weeks she’d call, or I’d call and I’d say, ‘Hey, are you going to come today because I’m out here by myself? I just feel like a crank,’ ” he says. “So we kind of kept each other company on that picket line when no one else was around. And we did street theater and other kinds of innovative protests.”

Fullinwider and Sara developed an enduring friendship and a continuing collaboration as activists. They would go on to serve on the board of the Dallas Peace & Justice Center and to co-found Mothers Against Police Brutality. But their first partnership didn’t have much success. In the end, Hinojosa didn’t lose his job. Sara lost hers.

“My principal was like, ‘You have to stand down. You’re on the news. You’re new. Your paperwork’s not—we haven’t inked anything. You need to lay low. You can’t be out there like that.’ And I’m like, ‘Well, I have to be out there like that. I cannot teach what I’m teaching—I cannot teach civics, I cannot teach history, I cannot teach these things and not have an active role in this moment.’ ”

Though it was an easy choice for her, she still can’t believe DISD gave up on a homegrown teacher so quickly. “They could have had me for life!”

Instead, the rest of the city got her.

Sara has one of the most important traits an activist can have, which is a voice made for a megaphone. It’s not so much its sound as what she does with it. But let’s talk about that sound for a moment. Sara’s natural tone is what I would call urgently maternal, as though everything she says is being addressed to a teenage boy about to hop into a car with his friends on a summer night, sitting right between “Be careful” and “I love you.” It’s serious and sharp but warm. When the world is testing her, and it often is, just a note of exhaustion might creep in to alter the chord structure, change it to a minor key. It’s not the sound of giving up or giving in. It’s the crackling of that fire inside her, an implied “Can you believe we are still dealing with this?”

OK, then, now: how she uses it. After leaving DISD, Sara took a job with UTD. She is now the associate director for leadership initiatives with the school’s Institute for Urban Policy Research. She will give you facts and figures, and she will footnote them with the relevant Pew study. In conversation, Sara makes references to writers like Morrison and Jordan, to philosophers like Michel Foucault and Paulo Freire, and expects you to keep up.

But she also does not shy away from actually saying, “Can you believe we are still dealing with this?” Because of that energy, she is able to speak in soundbites that never come off as rehearsed or shopworn. And she knows how to make her audience absorb the material, using analogies and real-world examples to reach right to the heart of the matter, or simply to your heart. She makes talking points come alive.

If you’ve been to just about any major demonstration in this city in the past decade or so, you’ve no doubt seen her.

“When the Washington Post and the Guardian first began counting the deaths by police, we finally had a credible figure for annual deaths, and it was about 1,000 annually,” Fullinwider says. “In presentations, I began to push this figure to show the scale of the crisis—that it was an urgent national crisis—and, later, that the 1,000 deaths haven’t declined since 2015 despite greater public awareness. But Sara would face an audience and say, ‘I’d like each one of you to close your eyes and picture three people you love.’ After a moment, she’d say, ‘Open your eyes. That’s how many people were killed by police in America today. And they were each loved by someone.’ She made them feel it.”

I remember the first time I heard her speak. It was May 4, 2017, and she was standing in a field at Virgil T. Irwin Park in Balch Springs. A few days earlier, 15-year-old Jordan Edwards had been shot and killed by a police officer named Roy Oliver. The park wasn’t far from where Edwards had died, and a few hundred people had gathered for a candlelight vigil in his honor. A group of faith leaders, including Imam Omar Suleiman and the Rev. Dr. Michael Waters, spoke.

When it was Sara’s turn to address the crowd, she spoke of how it takes some species of butterflies 14 generations to migrate from Canada to Mexico, each moving a little bit farther down the path toward their ultimate destination. She suggested that this is how we should treat this situation: each successive generation must push further and further, demanding more justice each time.

Sara has been part of that push since she and Fullinwider helped Collette Flanagan start Mothers Against Police Brutality, in 2013. That year, Flanagan’s son Clinton Allen was killed by a Dallas police officer named Clark Staller, shot seven times, the last time in the back. Allen was unarmed. The former IBM executive wanted to do more than just create a foundation that would serve as a tribute to her son. She wanted a national organization that would be a voice for families and would fight for changes in policy and practices. Flanagan met Sara through a mutual friend and knew she had found someone who could help her do that.

Since its inception, Mothers Against Police Brutality has been a strong and vocal proponent of transparency and accountability in policing. The organization hosts political education workshops and works with a network of 200 families to help with their individual cases and connect them with other families and resources. In June 2017, the group led a march through Uptown, ending at Pike Park, where Fullinwider unveiled a sign unofficially renaming the park after Santos Rodriguez, the 12-year-old killed by Dallas policeman Darrell Cain in 1973, just a few blocks away. Two days later, the first indictment of a Dallas officer in 40 years was handed down in the fatal shooting of Genevive Dawes. When Botham Jean was killed by off-duty DPD officer Amber Guyger, in 2018, the department instituted a policy, long advocated by MAPB, to drug test all police involved in excessive and deadly force cases.

“We’ve changed the narrative around policing in this city,” she says. “And across the country, we’ve been part of that narrative change. Never before the existence of Mothers Against Police Brutality did you hear people talking about 50 years of unaccountable policing. It’s our data, our research, our talking points that have become every headline.”

Mothers Against Police Brutality also allowed Sara to change her own narrative. Her way of honoring her father had always been pouring herself into helping others. With encouragement from Flanagan, she began talking about what happened to him, what happened to her that October night in 1992.

Her parents had been arguing, and at one point her father had picked up a knife. Her mother called 911, but Tesfaie had calmed down by the time two police officers arrived at their house on Eddy Sass Court. Tesfaie was a gentle man who spoke five languages and devoted a room in the home to wounded birds he would find and nurse back to health. He was a gardener who could grow anything, make anything beautiful. What was going on with him that night? No one will ever know. He needed someone, but not someone with a gun. He needed help, a mental health professional maybe, a person to talk to, help him figure it out. Not a gun. The police said Tesfaie “threatened” his wife and the two officers with the knife. Vicki disputed that account. The only thing that’s certain is Sara was standing behind him with her mother and her 1-year-old sister when the shooting started. Part of her life ended then, too.

Talking about it couldn’t give her closure. Nothing could. Not even meeting one of the officers years later who had shot Tesfaie. But it helped her in her work, and that helped her father take on a new life. Not the one he had been denied, but it was something, and Flanagan had given that to her.

“And so I thought I was saving her and she saved me,” Sara says.

Sara has another trait that is essential to activism, and that is a deep need to get others involved. I don’t mean out in the streets with protest signs, rallying to her cause, though she has never had much trouble on that front. Her ambition is bigger than that. She is not just looking for more followers but more leaders, too. She is constantly trying to lift others up, highlight their work, give them an opportunity. During our conversations for this story, she brought up at least a dozen other people who deserve to be written about. When it came time to have her portrait taken, she suggested we consider three Black women photographers. She isn’t just trying to get more seats at the table; she is working on building a new table.

She met Eve Arreguin in October 2017 when she appeared on De Colores Radio, the podcast Arreguin hosts with Rafael Tamayo. Within a few months, Sara had enlisted her to appear on a panel, the first time she had ever gotten such an invitation.

“That’s another beautiful part about her is she’s very much someone who will say your name in a room,” says Arreguin, the community engagement specialist for Big Thought, an education nonprofit that works to close the opportunity gap for underprivileged students. “She does this thing where she’ll rope you into something and you’re like, But I’m not ready. And she’s like, Well, too bad. And so she very much has like the big sister effect, I guess, is kinda what I would call it. Because she looks after you, but she’ll push you to this uncomfortable place because she believes in you more than you believe in you.”

She met Jodi Voice Yellowfish, an Indigenous organizer, in 2015, when they worked on a project together with Complex Movements, an arts collective out of Detroit.

“If anything comes across her in her life that she thinks is perfect for somebody, she makes a point to find you and make sure you’re connected, or you have the right info or you’re in the right place at the right time to move your work forward or to support your family. She’ll definitely step aside and give you the time to share what you need to know, and that doesn’t always happen with organizing and activist circles.”

She met Maria Yolisma Garcia a decade ago, when Garcia was a student at Woodrow Wilson High School, trying to close the gap on parental involvement. “Considering Woodrow was very much a Hispanic-serving school, there wasn’t a lot of access and resources for Latino parents,” Garcia says. “Sara kind of helped me lift my voice. I credit a lot to her mentorship throughout the years. I always just think about if I had not had somebody to guide me or really just let me know that, even as a youth voice, it’s still something very powerful.”

She met Kristian Hernandez in 2017, at a community meeting Mothers Against Police Brutality set up to discuss what they wanted in a new police chief, before U. Reneé Hall was hired. Hernandez, a national political committee member of the Democratic Socialists of America, saw something different in Sara.

“I think that there are people who very easily and I think very frequently kind of fall into activism as a way to sort of fill a gap,” she says. “I mean, it just almost seems like they’re looking for something, so it kind of gives them this chaotic energy. But I think actually Sara always has a very calming energy, even though she has the urgency required for this work. But I think there’s just like a peace that’s brought by the fact that she knows that we’re moving in the right direction.”

Another generation of butterflies pushing just a little bit further.

“It can be really hard to stay on track,” Hernandez continues. “A lot of people really are drawn to activism where they kind of just can show up and, you know, they don’t really have to build long-term or help develop leaders long-term. And it takes a lot more diligence and a lot more intentionality to actually fight for things that don’t have an immediate payoff and to invest in other people so that the movement at large grows. She has a lot of humility and is always trying to push other people to the forefront.”

It’s a trait that Sara inherited from her gardener father: the patience to grow something beautiful.

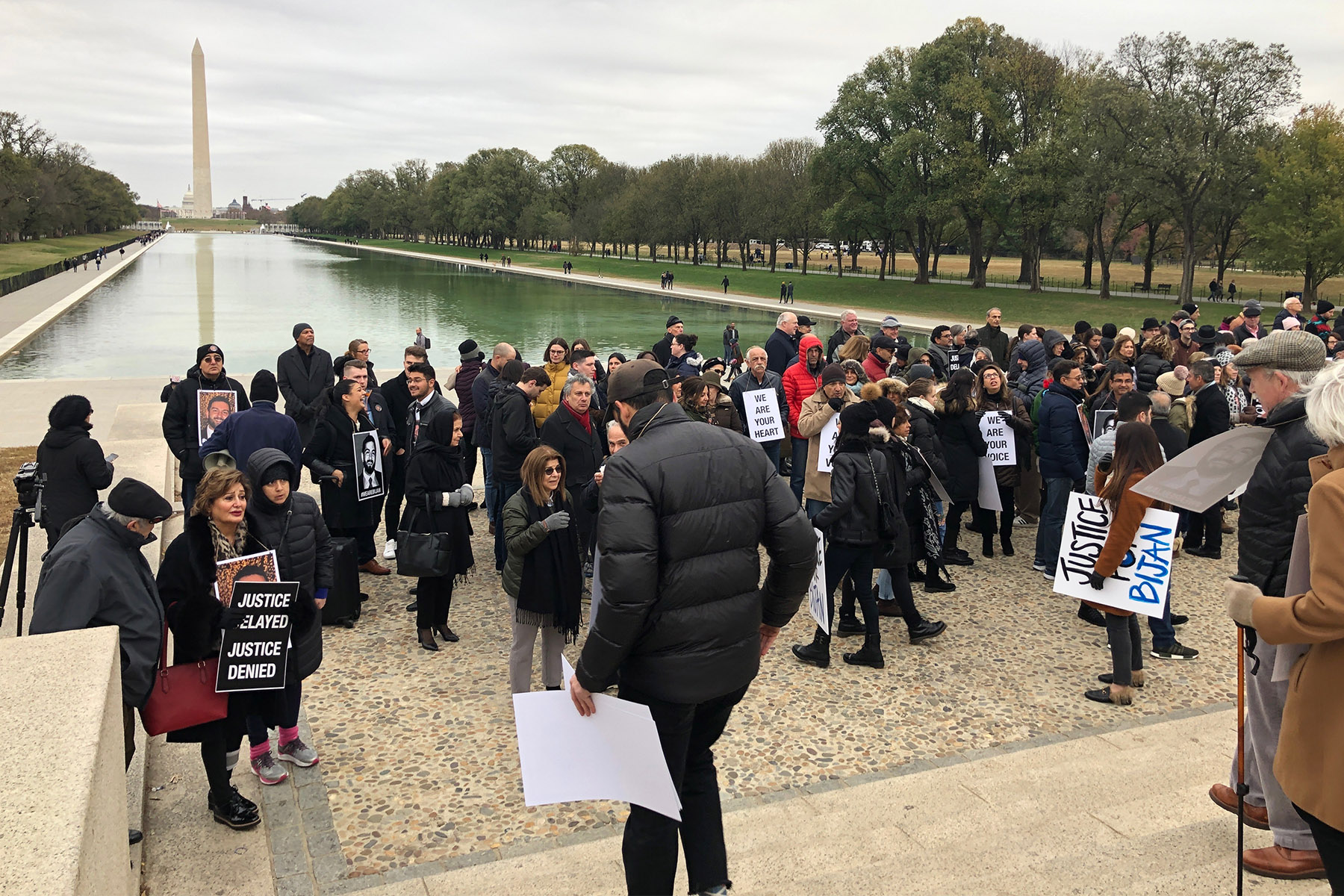

In the months following the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis on May 25, people across the country began calling for cities to defund their police departments. Dallas was only different in that its activist community was more prepared than most for that particular fight.

Sara wasn’t happy about it, of course not, but this was the moment she had been waiting for. Not this, exactly—who could have expected a global pandemic?—but something like it. The right time for everyone to pay attention to what she had been talking about for years—that there were better, smarter alternatives for public safety.

Now it was here and she was ready. They were ready: early last year, Sara and other activists had come together to form Our City, Our Future, a BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and people of color) collective of women and nonbinary citizens, including Arreguin, Voice Yellowfish, and Hernandez. The group had started to coalesce around opposition to the city’s juvenile curfew but found its focus after the murder of Muhlaysia Booker in May. They didn’t have enough time to affect that budget cycle, but it gave them experience.

“Generally, we’ve been playing defense,” Sara told me in early August. “Last year in the budget conversation, we were talking about reimagining public safety and we were just saying—we weren’t even saying cut into the police department’s budget. We were saying, ‘Don’t increase it.’ That was the fight we were in last year. This year, we’re saying, ‘We want half! Take it away.’ I think there’s been a real reckoning and understanding how so much money has been spent on policing and how little we’ve gotten for the—what has been the return on investment?”

Sara and I were talking on a Thursday afternoon in the downtown offices of Mothers Against Police Brutality. She struggled with the mask she was wearing as she spoke, as if the rush of words escaping from her mouth were piling up behind the cloth. She was excited, cautiously optimistic. The next day, City Manager T.C. Broadnax would release his budget for the 2020–2021 fiscal year, and there was reason to hope he would incorporate at least some of what Our City, Our Future was asking for. Maybe not everything in the $200 million budget they had submitted, paid for by cutting police funding by a third, but real, substantial change.

In June, a coalition of faith leaders and activists (including Sara) had authored “10 New Directions for Public Safety and Change,” which led to a countywide task force put together by Dallas County Judge Clay Jenkins. It counted among its membership seven city managers (of which Broadnax was one) and representatives from law enforcement, along with the creators of the original document. The goal of what came to be called the Working Group on New Directions for Public Safety and Positive Change was to address public safety by going after the causes of crime, not the effects. They met via Zoom for six weeks. Sara and Fullinwider arranged for testimony from people directly impacted as well as experts from around the country on alternative non-police solutions to public safety issues.

And then, on August 7, Broadnax unveiled his budget. Though it funded a citywide expansion of the RIGHT Care program—a partnership with Parkland Hospital that sends out mental health social workers on some 911 calls—and found money for a few other steps in the right direction, Broadnax’s budget pointedly did not take any money away from the police department. “It was a big F-you,” Sara says the next afternoon.

Over the next month or so, Sara and OCOF’s organizing talents were on display, as dozens of citizens appeared before the City Council, asking for money to be reallocated from the department and invested back into the community, almost all repeating the group’s $200 million ask. But the initial budget didn’t change much. It’s maybe more nuanced than this, but it can be accurately reported that the Council wouldn’t even agree to defund the department’s mounted unit. The Council did pass an amendment cutting the department’s overtime allowance by $7 million, but DPD still received $8 million above its previous overall budget. Broadnax’s budget passed 9–6.

And so, it’ll take at least another year but probably longer, another generation of butterflies to inch closer to the destination.

“To say, ‘I’m hard on crime, I’m going to invest in police, because I care about you,’ that’s an easier thing to say, and to get people to get behind, than saying, ‘You know what? I’m going to radically change our zoning processes, and I’m going to invest in public housing and parks and libraries,’ ” she says. “That’s a harder sell, and it’s more complicated, and it doesn’t have a quick and shiny slogan. So I can understand why politicians lean so far into it. But it’s killing us. It’s not working, and at this moment, we’re waking up this morning to another city on fire and another rebellion popping up. The people are tired of it.”

Sara is almost as old as Tesfaie was when he died, and these last few months have been some of the most trying times since then. It has required every bit of that patience she got from him. She thinks of what has been lost, the people, the possibilities. She thinks of where she wants to be.

“I’ll say what I’m pushing for is, I have a 10-year-old,” she says. “I want to go to the park, spend time with my son, play with him. This is not like—this is not what I want to do. I want to create a world and a society where I can have the freedom and the peace to do those things. Where all of us have the freedom and the peace to do those things.”

Until we get there, she’ll keep fighting.

Author