There was never any doubt that Jerry Jones and his oldest son Stephen would become business partners someday.

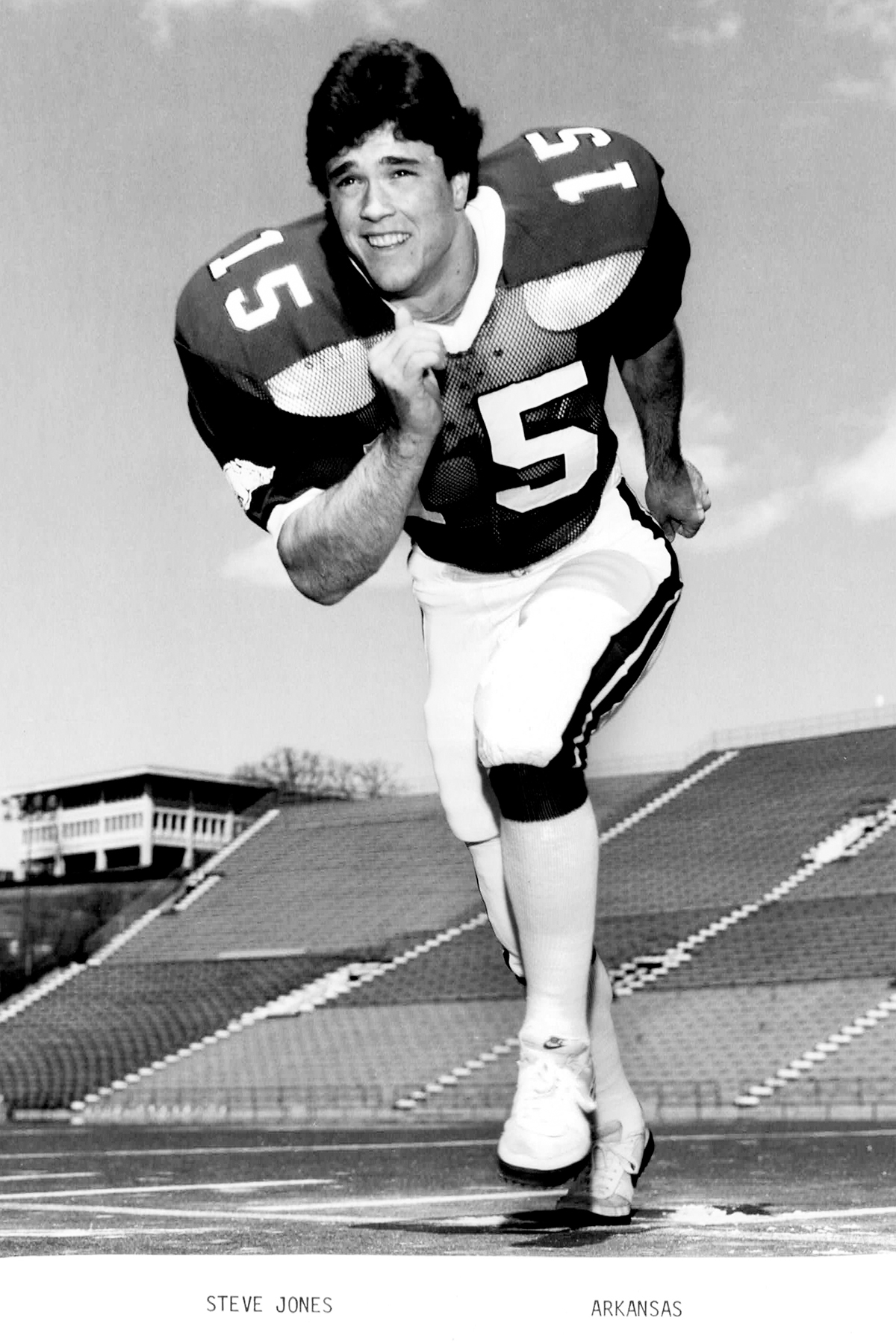

When Stephen was a student and football player at the University of Arkansas, Jerry would visit and they’d map out business dreams so late into the night that Jerry would sometimes sleep on the dorm room floor or in a roommate’s bunk.

Although Stephen had other scholarship offers—including one to Princeton where he and Coach Jason Garrett would likely have been teammates—he was dying to be a Razorback like his father, and grew up hearing stories about his dad and his teammates winning national championships. Stephen would go on to letter all four years.

Along the way, he also earned a degree in chemical engineering. The plan was that he would eventually assume leadership in his father’s oil business and would learn everything there was to know about the industry.

“I believe in blurred lines,” Jerry says. “I like for the key people to be able to cross over lines. I like for them to be involved in several disciplines. You say, well, that looks like it creates a level of ambiguity or a level of nobody knowing what to do. No, I want people that can handle this and be accountable.”

Jerry first publicly promoted this theory back in 1989 at his initial Dallas Cowboys press conference, saying: “I intend to have a complete understanding of contracts, jocks, socks, and TV contracts.”

Stephen’s energy career took a sweeping turn with Jerry’s pursuit of the NFL team. The chase took time and money. To make the deal, Jerry would sell his majority interest in the NBC affiliate in Little Rock among other cherished assets. One sticking point stood in the way. The team’s owner at the time, Bum Bright, insisted that new owners keep the current GM, Tex Schramm. Stephen remembers how that played out.

According to Stephen, Jerry told Bum he wasn’t going to pay that kind of money for something losing $1 million a month and then let someone else run his business. Bum called back and told Jerry that Tex was out of the picture … that “his time had expired.” All that was left was coming to terms on the price.

The price was $140 million—or about $110 million less than what Jerry paid earlier this year for a yacht. Stephen had been in on negotiations and, at his dad’s request, had gone over the team’s books and P&Ls. But he was still surprised to get a call from Jerry asking him what he’d think about starting work immediately for the Dallas Cowboys.

“I said, ‘Oh man, are you kidding me? I’m living in Fort Smith reading drilling logs, and I can come down to Dallas, and I’m single, and be a part of the Dallas Cowboys?’ ” Stephen says.

He would not be just a part of the Dallas Cowboys but eventually its chief operating officer, executive vice president of player personnel, and president of AT&T Stadium. He was also a part owner of the club. As things stand now, parents Jerry and Gene Jones, own 51 percent of the team, while Stephen, his sister Charlotte (executive vice president and chief brand officer), and his brother Jerry Jr. (executive vice president and chief sales and marketing officer), equally own 49 percent of the club and are significant partners in all other Jones endeavors.

Forbes most recently valued the Cowboys franchise at $5 billion. However, the real estate arm of the family enterprise might be even larger. Stephen has many fingerprints on the real estate brand, Blue Star. It controls more than 500 acres in Frisco, including The Star, a 91-acre, $1.5 billion mixed-use development that’s home to the Cowboys world headquarters and training facility, a 300-room Omni hotel, a Baylor Scott & White healthcare facility, and scores of restaurants and retail shops. Dr Pepper recently announced that it would move its headquarters to The Star, signing on for 350,000 square feet overlooking the practice field.

Stephen also manages most major events that come to AT&T Stadium in Arlington and The Star in Frisco.

As if that weren’t enough, he also plays a significant role at Comstock Resources, a publicly traded energy company in which the Jones family acquired a controlling interest last year. Comstock recently made a more than $1 billion bet buying in on one of the largest natural gas basins in the country. It’s here where Stephen’s early engineering work in the oil and gas industry comes into play. “I have a comfort level,” he says. And connections. “Some of the top people I worked with when I was in my early 20s are still top people in the oil and gas business.”

Although salary compensation may be different, Stephen, Charlotte, and Jerry Jr. share equally in ownership interest in all the companies and receive dividends on an annual basis. “Jerry wants us all to be motivated for the businesses to do well,” Stephen says.

Holding the Baton

There is a general perception both in the media and around the NFL that Cowboys COO Stephen Jones has attained more power and influence in the Dallas Cowboys front office. Stephen, who’s 55, allows only that after 30 years on the job, Jerry is a lot more comfortable delegating assignments to him, because he knows they will get done. On the other hand, he argues that when people ask him about now having a bigger say, he says, “I just don’t buy into that. At the end of the day, Jerry has the final call.”

For his part, Jerry says Stephen was doing a lot more a lot earlier than people think—much earlier. “When we first bought the team, in those ensuing years right off the bat, Stephen was in a position of influence and responsibility much earlier in every aspect—the entire picture, football, banking the bowels of stadium operation, concessions, marketing—every aspect,” Jerry says.

So why are we not seeing a passing of the baton?

“He’s always had the baton,” Jerry says. “That’s it. He’s always had possession. This young man early on—and to this day—has been operating in blurred lines with accountability and has held that baton.”

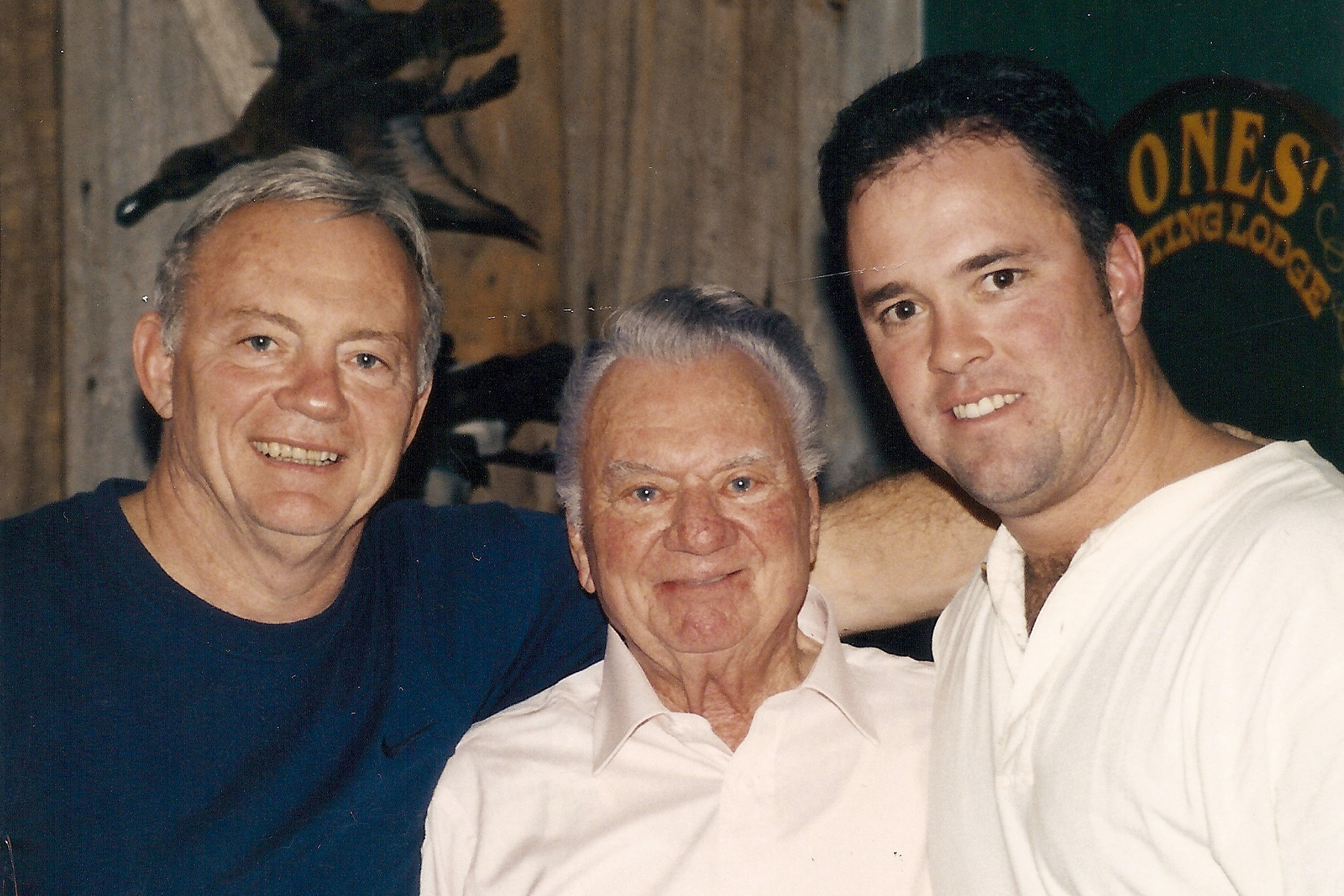

If Jerry Jones has one regret, it is that he did not stay in business with his father. Known to many as “Papa Pat,” he owned a supermarket in North Little Rock. About four years after Jerry got out of college, he went in a different direction than his dad. “I went in the oil and gas business, and he wasn’t interested in doing that. Consequently, I missed 25 years or more that I could have been working with my dad,” Jerry says. “Even though I saw him, I counseled with him, and I had a normal father-son relationship, life would have been so much more fulfilling.”

When Jerry was about 30 years old, he wrote a long letter to his father telling him just that. Decades later, Stephen explains: “He loved my grandfather, Papa Pat, and, you know, they went through a little stage there where dad just said, ‘Hell, this is so demanding. I want to go on my own and see what I can do.’ He didn’t want to have that happen again with us. He has been so respectful and doesn’t take anything for granted within our relationship.”

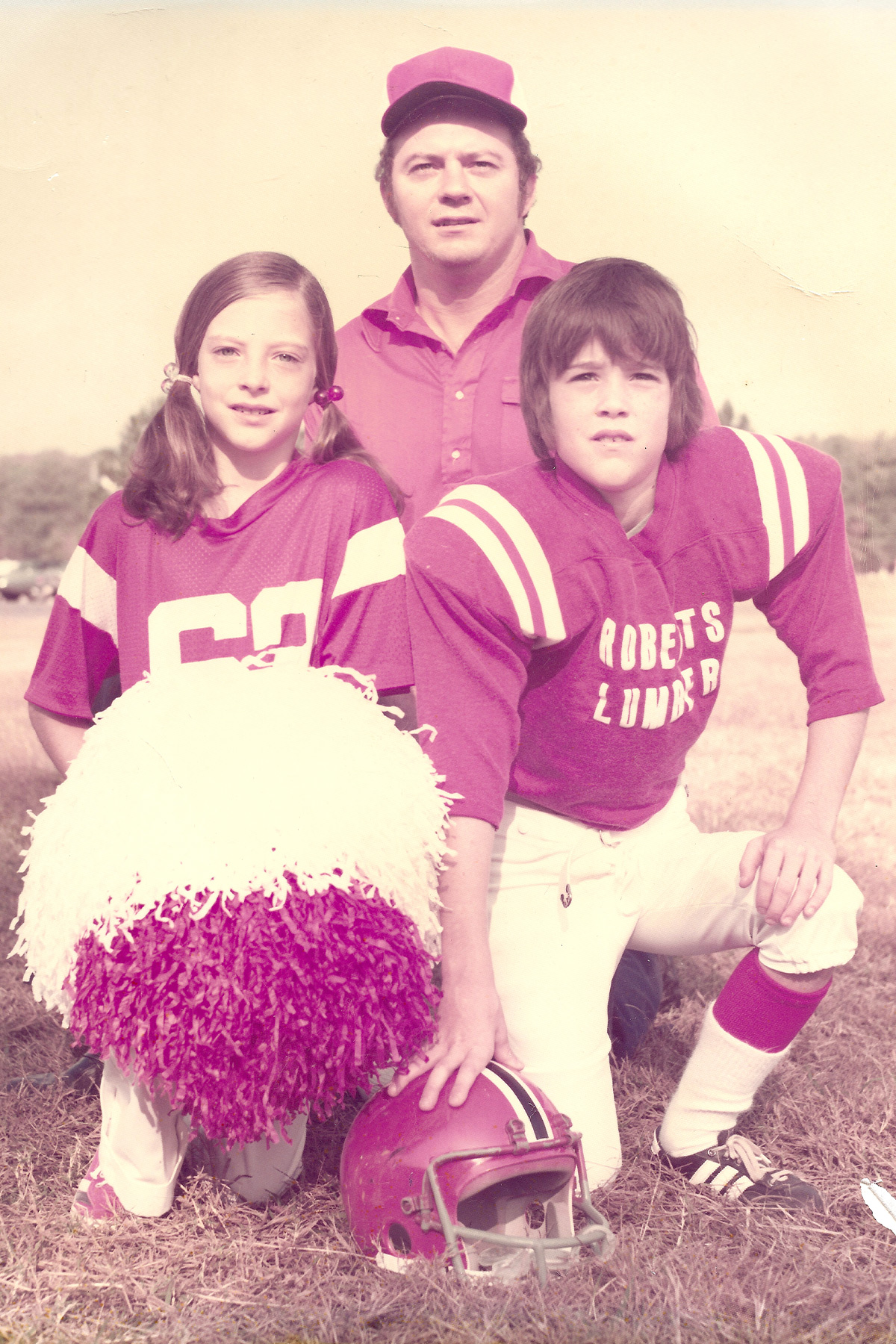

This may be part of the reason that Jerry and Stephen bonded so early and so firmly. Stephen remembers his dad going back and forth to Oklahoma working in the oil fields, flying in for a couple of his or his sister’s or brother’s practices a week, and then flying or driving right back out that evening.

Stephen says his parents spent a lot of time with him and his siblings; he learned from it and puts it into practice with his own children—three daughters—Jessica, Jordan, and Caroline—and a son, John Stephen Jr. His mother, Gene Jones, also gives Stephen’s wife a lot of credit. “She is an amazing woman and makes life run so much smoother.”

In The Trenches Together

Jerry says that his initial instinct when Stephen came out of college was to help mold his son. But it soon became apparent that the one who got the most out of that effort was not the son but the father. “When I look back on it, the Cowboys and all of these other entities have benefited so much more with Stephen than if it had been somebody else sitting there in his shoes,” Jerry said.

Jones says he cannot recall an important meeting when he did not have Stephen by his side.

With all the time personally and professionally they have spent together, there of course have been disagreements between father and son—some of them fairly animated. When Stephen was still high school, he and his dad—going against family tradition—agreed that Stephen would not work one summer. He would make preparing for football his work and regime. They both agreed to the deal.

“He is often keeping me grounded and actually keeping me less controversial.”

Jerry Jones, on how his son Stephen helps keep him out of trouble

Jerry and Gene were away for a short time that summer, but long enough for Stephen to promote a classic pool party in the family backyard. Jerry came home both early and unamused. He fished Stephen from pool and let him have it. Stephen was ordered to go directly upstairs put on a coat and tie and head to Wendy’s to apply for a job as a cook. The franchise owner was in on the stunt and told Stephen to report to work the next morning, prepared to clean the grease pits.

Jerry, renowned throughout the NFL for giving second chances, gave Stephen one but with this admonishment; there would be no more broken deals.

A more public disagreement took place at The Mansion on Turtle Creek in 1995 and involved the free agent signing of star cornerback Deion Sanders. Stephen believed Sanders’ asking price was excessive. He told his dad so, who, unfazed, announced he was walking down the hall of The Mansion to announce they would accept Sanders’ demands.

Jerry recalls what happened next: “We had just entered the salary cap era of NFL. Stephen kind of grabbed me by the shoulders, and said, ‘Now wait a minute, don’t go back there unless we sit here and talk.’ And I said, ‘Well, Stephen, I’m going to be very candid with you. I know what you’re saying here, and you can always second guess the other guy a little bit, but I think this is where we’re going to end up.’ All of a sudden he pushes me up against the door and has actually got his arm up against my chest. I’m saying, ‘Are you going to hit me? What in the world has gotten into you?’ He backed down and said, ‘Doggone, I didn’t know you were that ready to go on this. I should have weighed into you a lot quicker.’

The substantiveness of our relationship allows you to have that kind of quid pro quo yet maintain the respect of the father-son relationship.”

A less famous argument comes with a narrative twist from Stephen. Common knowledge was that Jerry was very much intrigued by Texas A&M quarterback Johnny Manziel in the 2014 draft. Jerry was the only member at the draft table considering the exciting, highly publicized quarterback. He was surprised that no one had taken the glorified Heisman winner. He turned to Stephen to ask him what he thought, and Stephen insisted they take Zach Martin. According to Stephen here is how the rest of the event played out:

“Manziel falls to us,” Stephen says, “and Jerry is looking over at me and he says, ‘What do you think?’ I say, ‘I think we go with Zach Martin.’ He says, ‘You gotta be kidding me.’ Well, we go around the room, and everybody from the head coach to the coordinators to the scouting staff is thinking the same thing, but nobody even wants to look up at him. It was painful.”

Stephen says Jerry was not believing it and thought Manziel could be one of the greatest of all time. He had performed at a high level in the SEC. “I said, ‘We need to pass on this one,’” Stephen recalls.

Roll the clock forward a couple of minutes, and the Cowboys officially selected Martin. “Of course, it’s just silence,” Stephen continues. “Usually we’re all celebrating right after we picked someone, and Jerry hit me real firm on the thigh, and says, ‘I didn’t get to buy the Dallas Cowboys, and I didn’t get to accomplish great things by making middle-of-the-road decisions. If that’s how you live your business career, all you’ll ever be is average. You just did something very average.’ He got up and walked out, and everybody’s quiet. About 10 minutes later, he walked back in, comes up to me and says, ‘You know, I love you. I didn’t mean that. We probably did the right thing. Let’s move on.’ And then everybody started smiling, and there we went.”

More often than not, Jerry and Stephen are on the same side. This was the case during a bar fight in Aspen at the Little Nell hotel. Most of the Jones family was seated at a table when some overserved men started mouthing off about a redneck coming in and taking out former Cowboys head coach Tom Landry. The manager was told about the situation but said he couldn’t make people leave.

“When the manager said, that, well, ol’ Stephen kind of looked over at me,” Jerry says. “The next thing I knew tables were turned over and bottles and glasses were flying. It was the damnedest thing you’ve ever seen.”

Apparently, Little Nell patrons still talk about it, and it is part of Stephen’s reputation for what Jerry calls, “having a physicalness about him.”

Gene Jones, the petite, former Miss Arkansas USA, assures that she threw no punches. “I knew those boys could handle it,” she says. “Especially Stephen.”

“He will use his head, but he sure will stand his ground,” Jerry adds.

A Strong Foundation

Gene and Jerry were married as juniors in college. Stephen arrived the next year, right about graduation time. “I was a young mother and we just kind of grew up together,’ Gene says of her son. “He made a lot of good decisions as a young man and great friends. For instance, I might ask him why he never plays with the boy next door and he would say, ‘Mom, his lifestyle is a little different than I know what you want from me.”

Much of Stephen’s restraint and work ethic was learned in Little Rock at Catholic High School for boys where the principal, Father George Tribou, required acceptable haircuts, khaki pants, white shirts, and neckties. It was not just “a good academic school,” Gene says, “but mainly it was about teaching young men to grow up and do right. … Father Tribou carried a pair of scissors in his coat pocket,” Gene says, adding that Stephen would sometimes return home a casualty to one of Tribou’s hair styling efforts.

At home, the older brother, Stephen, was sometimes considered over-protective of his sister. He denied even his best friends the opportunity to court her and causing Charlotte to announce she would be attending Stanford, far away from where Stephen was studying.

“Of course, Stephen’s dad,” Gene continues, “is real demanding of our children and always was when they were young. But he also gave them great opportunities and he really wanted for them to have a job and put them in charge.”

Jerry can think of few meetings of any consequence when Stephen wasn’t involved. The respect the father and son have for one another has been key to the relationship’s success. Stephen contradicts those who think he looks forward to having the final call in Cowboys business matters.

“I love our partnership, and I hope it goes on for 20 more years,” Stephen says. “I don’t feel like there’s any void missing because, you know, at the end of the day, I get to do so much and influence so much. It just doesn’t eat away at me that I’m not the final shot-caller.”

“We had some humdingers.”

Stephen Jones, on his battles with former Cowboys head coach Bill Parcells

Jerry admits that Stephen is more conservative. “It makes sense when you think about it, because I initially had to go with less, and so you could make a case for more risk,” Jerry says. “The hardest steps going up the ladder are the bottom ones. Stephen sometimes has the idea that he has to make decisions and protect value, protect some assets. At the same time, he’s obviously learned from experience. He’s competed against real tough businesspeople and problems. He’s had his nose bloodied a lot, and we are better for that.”

In particular, Jerry thanks Stephen for his calming influence at league meetings and in dealings with the commissioners. With Paul Tagliabue and Roger Goodell, there were times when Jerry wanted to push harder or be more vocal. Stephen tempered the situation because, says Jerry, “he realizes, the importance of the league as a whole rather than just the Cowboys. Stephen has done a fabulous job, balancing that out for the last 30 years. He is often keeping me grounded and actually keeping me less controversial.”

More than a few folks rely on Stephen’s ability to gently curb his father. “I have had lot of people call me about this,” Stephen says. “Actually, my brother and sister, I think they’ll tell you this. But they count on me sometimes to get dad to tap the brakes. They might ask, ‘Are you sure we should be doing this?’ They’ll ask me those types of questions, especially when it comes to the oil and gas and some of our real estate.”

The ability to cultivate the kinder, gentler Jerry has come with time. “I didn’t have that skill set when I was in my late 20s and early 30s,” Stephen says. “I was just learning what he’s going to ask and what he was going to want. You know—what are his hot buttons?”

Both Jerry and Stephen say Jerry has learned to have full confidence in his COO. Jerry depends on Stephen to work through many of the details of a business proposition before a decision is made. More than anything, Stephen says he has learned how to sell ideas to Jerry. He knows the questions that his father is going to ask. So now when he brings something to his dad, Jerry has confidence in Stephen’s opinion.

In most cases, you would assume that younger folks would be more inclined to take risk and the older people would prefer buying AAA bonds and avoiding hazards. Although Stephen acknowledges that Charlotte, Jerry Jr. and a lot of top executives agree that Jerry delegates more so now than ever, he says that for a man of his age, Jerry’s tolerance for risk is still very, very high. “That is one of the things unique in him,” Stephen says “He is the patriarch, and I think it’s going to be more difficult when he’s not here to take those risks. I mean, right now, he makes the final call.”

Stephen acknowledges that when he and Charlotte and Jerry Jr. are in charge—when Jerry Sr. is no longer here—it’s going to be difficult. “I think that we may take fewer risks when he’s not here than when he is here.”

Building Character

Stephen Jones has shown great respect for his mentors over the years. Along with both of his grandfathers, there’s Mike McCoy, who was and remains a close associate of Jerry Jones in the oil and gas business; the late George Hays, Jerry’s first and longtime vice president of marketing; Jack Dixon, Jerry’s first CFO with the Cowboys; the late Bruce Hardy, legendary general manager of Texas Stadium; and Father George Tribou, also deceased, the principal at Catholic High School for Boys in Little Rock. But another name also comes up time and again: Bill Parcells.

By 2003, the Dallas Cowboys were limping along. Not only had Jerry Jones fired popular coaches Tom Landry and Jimmy Johnson, but “America’s team” was walking the tightrope of irrelevancy. Gone were the days of Super Bowl titles and division championships. Hello, Dave Campo and three straight 5-11 seasons. “The team wasn’t playing well, we didn’t have good personnel, we didn’t have good coaching, and, you know, we deserved it,” Stephen says of the criticism the team received.

A dramatic change was needed. Ahead was a crucial vote asking Arlington residents to approve a gigantic new stadium. That’s one of the reasons Jerry hired Bill Parcells. “Things were starting to rock around here, and we needed a really high-end coach,” Stephen says.

Parcells agreed to take on the Cowboys as his latest reclamation project. He was a winner—of playoff games, division titles, and Super Bowls. He was a Yankee and carried himself with a no-nonsense, tough exterior that he would use to bring order and discipline to a team short on both of those attributes, as well as talent. Somehow, in his first year, Parcells would take a lifeless team that had suffered double-digit losses the previous year and take them to the playoffs.

Parcells was every bit the personality sports talk show hosts relish in what was sure to be the oncoming train wreck of a relationship in the front office. “People were betting that we wouldn’t last a month being together right down the hall from each other,” Jerry Jones says.

You can give Stephen much of the credit for standing between the two mega personalities. Parcells says he told Jerry they needed to use Stephen as a buffer, rather than go toe-to-toe with each other. Stephen would regularly meet with Parcells most mornings. “He challenged me time and time again,” Stephen says, “to see if I’d stand up or back down and let him run over me. We had some humdingers.”

Two of those humdingers happened on draft day. Stephan and Parcells each have a favorite story.

Stephen first. Days before the 2005 draft, Cowboys scouts and coaches were all in agreement the club would first take a pass rushing linebacker, either Maryland grad Shawne Merrriman or DeMarcus Ware, hailing from Troy University. About four days before the draft, some information came forward that dropped Merriman down the Cowboys draft board and moved Ware to the most wanted slot—but not in Parcells’ mind. The head coach now wanted to take the defensive end from LSU, Marcus Spears. Parcells was worried that Ware would be entering the league playing a new position and finally bristled, telling Stephen, “I’m not fucking taking DeMarcus Ware.”

So Stephen replied, “I said, ‘come on now. We’ve been saying all along it’s Merriman or Ware, damn it.’”

Parcells responded with a cascade of profanity, basically suggesting that he knew all along that Stephen and Jerry would not let him put his team together. Meanwhile Stephen countered with the notion that not one scout had Spears ranked above Ware.

“And I go, ‘This is a consensus,’ ” Stephen said. “And he goes, ‘It’s not my consensus. I’ll tell you what, pick, who in the fuck you want, and I won’t be there.’ And I mean, he stormed out, he was pissed. He said, ‘I fucking knew y’all would screw me around.’ ”

So roll the clock forward to the draft, and Parcells is a no show in the Cowboys war room. The draft board has been finalized, seating is arranged, but no Coach Parcells, until “right about the time they’re making the first pick, here comes Bill,” Stephen said.

Bill arrives dressed smartly in a coat and tie, looking quite the professional carrying his briefcase. He is stoic and not responding to Jerry’s attempt of icebreaking chatter. Just a few minutes before the Cowboys turn to pick, Bill is furiously writing something that he passes to Jerry.

Stephen is peeking over to see what it says. Basically, the document reads that if the player the Cowboys are about to draft does not average 10 sacks a year in his first three years, then Parcells gets three free trips on owner’s jet anywhere he wishes to travel.

Perhaps Parcells learned negotiation from his father, who bargained with unions and drafted labor agreements. The handwritten document was neat and official and even had a signature line with Jerry’s name and title printed under it. Jerry read over the note and began his own scribble, stating that the owner would agree to all of the above but inserted an amendment, providing that if the player did pile up those number of sacks, then the owner of the Dallas Cowboys gets to take the head coach’s girlfriend anywhere he wants on his jet. Jerry also put a signature line in for Parcells.

That exchange did break the ice, and Parcells said Ware would be a good pick. As good luck would have it, the Cowboys also got Spears later that round.

“Yea,” Parcells said, “they love to tell that one. But I bet they never told you the one about Witten, did they?”

Well, no, Bill so go ahead.

In 2003, early in the third round, it was agreed that the Cowboys would draft a tight end. However there was huge disagreement on who player that might be. The majority of the Cowboys drafting brain trust preferred Mike Seidman, the 6’4″ receiver from UCLA. Parcells said he could not believe his ears when the front office said they preferred a senior from UCLA over Witten. The debate went on. Scouts told Parcells they thought Seidman was the better blocker of the two. The way Parcells tells it: “Finally, I said ‘Let me get this shit straight (a favorite Parcells salutation). You want this kid who started just one year at UCLA, and I want this guy who was a four-year starter in the Southeastern Conference for Tennessee. So, let me ask you guys who beat Seidman out his sophomore and junior years, and what are they doing now?’”

Parcells had done his homework and knew the answer. Heads were nodding and the Cowboys ended up taking their best and most productive tight end in club history.

Stephen will tell you he immensely enjoyed those times with Parcells as head coach. And both he and his father tried to persuade Parcells to stay. For his part, Parcells says, “I wish I had started there earlier in my career. Their word is good, and I was dealing with people who were forthright and honest.”

When Parcells announced his departure after three seasons, rumors flew that he and Jerry had suffered a critical falling out. Some people blamed the mercurial receiver Terrell Owens, but Stephen knew better. In Parcells’ final farewell, he told Stephen, “If I’m going to coach anywhere, I would coach for you and Jerry. But you watch, I’m not ever going to coach again. I just don’t have the energy to do it the right way for you guys anymore.”

Through the Wins and Losses

In training camp in Oxnard this year, Stephen looked at an old news photo. It was a 1993 shot of a smiling Stephen with an equally beaming Hall of Fame running back Emmitt Smith. After they had finalized a new contract and ended a long, sometimes venomous holdout, Jerry had turned the matter over to Stephen with the warning that Stephen’s legacy would much depend on how those negotiations turned out. “I bet I was right at 25 then,” Stephen says. “I would sure like to have all that hair back.”

The next day, Jerry looked at the same picture and grinned that famous jackass-eating-cactus smile. He reminds that back then, Emmitt wanted the same kind of salary Cowboys quarterback Troy Aikman was getting. “He didn’t get that,” Jerry says.

This year, Cowboys all-pro running back Zeke Elliot was also holding out, and, again, Stephen headed up the talks for Cowboys ownership. “See,” Jerry says, his eyes sparkling, “he’s been doing this same thing for 30 years. It’s a misnomer to think that he has evolved into this. When Stephen is asked [about Zeke’s holdout] and says, ‘I’ve had days like this for 30 years,’ he means it. He has. Now, is he better today? He is eons better. I hope I am better, also.”

Jerry says that the most important and rewarding part of his job working with the Dallas Cowboys is the fact that he gets to work with his children on a day-to-day basis, through the wins and the losses. “I wouldn’t trade it for anything,” Jerry says. “And so, if someone asks me about a succession plan, I don’t have a succession plan. It’s just gonna keep being run by the people that are running it. What has happened in our family and certainly has happened with Stephen is that he has been such an integral part of how the Cowboys have evolved since we bought the team. He can look at what we have and say, ‘I did it.’ But he doesn’t.”

Instead, Stephen proceeds with the “blurred lines” strategy. He oversees the management operations for all aspects of the Dallas Cowboys and AT&T stadium. He supervises the team’s scouting and personnel department while also handling all the club’s major player contract concerns and leadership of The Star in Frisco, other real estate, and the oil and gas enterprises.

“He can do all those kinds of things, and I go with him on them because I know he has done his homework,” Jerry says. “He has the experience, and he knows the consequences. Hell, he’d like to have a Super Bowl worse than his next breath. He knows I would.”