Fort Worth was once home to one of the most progressive drug treatment centers in the country, but what made the Fort Worth Narcotic Farm unique led to its downfall. Founded in 1929, it was one of the first places where drug addicts were seen as those who needed medical help rather than purely criminals.

For several years, Oklahoma State associate professor of history Holly Karibo has been researching the Fort Worth Narcotic Farm in preparation for a forthcoming book on the subject. The facility, along with its counterpart in Lexington, Kentucky, was where addicts were both punished and treated, but Karibo argues that duality helped expand more punitive prison systems in the latter half of the 20th century.

Heroin and opiates had long been treated like legitimate medicine through the 18th and 19th centuries in the United States, but when the substances became illegal in 1914, much of their use went underground, leading to a culture of secrecy and abuse. As drug abuse grew and addicts filled up existing federal prisons, Congress established the narcotics farms in 1929 as a place to both treat and imprison drug addicts who had committed crimes. The facilities also served as a place where addicts could voluntarily enter for treatment as well.

“The farms signify a moment where public health and incarceration were working together at the federal level to try to alleviate the challenges the institutions were having,” Karibo says.

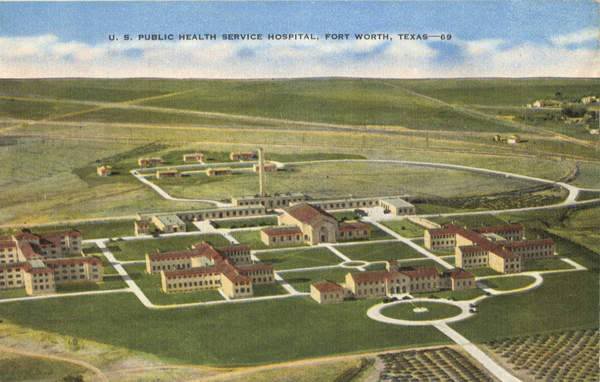

At the time, treating drug addicts as more than criminals was extremely progressive. While much of the public clamored for harsher punishments for drug addicts, the farms took a more compassionate approach to prisoners with medical issues. The Fort Worth farm was built about six miles south of downtown Fort Worth and was fully operational by 1940 after much lobbying from local boosters like Amon Carter. The 51-building, $4 million complex was the largest hospital of its kind in the country at the time, was run by the federal health service, and was officially known as the United States Public Health Service Hospital. It could treat about 1,000 people.

The duties of running a farm were part of the therapy and were linked with a bygone notion of a rural existence full of hard work, which is how mental illness was often treated in previous centuries. The removal from temptation and society was meant to build up one’s morals and self-control through hard work. The 1,400-acre facility included recreational and agricultural land, where farm work and animal husbandry were part of the curriculum and character-building.

After a few years of operating under the prisoner-patient model, where criminals were incarcerated while being treated with therapy for their drug addiction, the federal government began treating returning soldiers with medical and psychiatric care. After the war, drug supply lines were re-established, and the farm took on more patients, but more than half of those at the farm volunteered to be treated there.

As heroin became more popular and cheaper, it found its way into segregated neighborhoods that were heavily and disproportionately policed. As a result, Black and Hispanic patients became a more significant proportion of the farm’s residents.

Whether the patient was a prisoner or voluntary, they went through the same treatment that included methadone, psychiatric evaluation and observation, and occupational therapy that included work in the greenhouse, dairy, or another farm area. Drug addicts were seen as unable to hold down a job, so skill-building training was part of the treatment. Prisoners learned technical skills like shoe repair, radio and television repair, accounting, typing, and more. Patients also went through group therapy and socialization exercises.

Even though officials called the farms hospitals rather than prisons, there was still a fence, and guards and prisoners arrived in jumpsuits and chains. Voluntary patients were subjected to bed checks and other prison-like activities, and many of them did not last long at the farms. “The notion that addicts were morally, mentally, and physically incapable of stemming their urges, that they had, in the words of Treadway, ‘lost the power of self-control,’ justified that state’s use of various degrees of restraint,” Karibo writes in a 2018 academic journal, the Social History of Medicine.

Patients and clinicians alike felt the prison-like atmosphere was detrimental to rehabilitation for both prisoners and voluntary patients alike. Prisoners sentenced to the farm often saw their experience as doing prison time and were not committed to rehabilitation, which wasn’t a suitable environment for recovery. The rigid schedule and intermixing with the criminal element were not well-received by the voluntary patients, and they rarely stayed the recommended four to six months. One estimate found that only one in four voluntary patients followed the recommended treatment plan.

“That tension between the different type populations was evident,” Karibo says. “The life experience of prisoner patients compared to voluntary patients was really jarring and made them feel like they were a stigmatized population being housed with other prisoner inmates.”

The environment led to high recidivism rates for patients and prisoners at the respective narcotic farms. More than 50 percent of patients who had gone through the Lexington and Fort Worth hospitals later used drugs, a 1957 study found.

The high recidivism at the naroctic farms coincided with increased drug use, violence, and organized crime throughout the 50s and 60s, providing political cover for a more punitive mindset for criminal justice policymakers. In 1951, the first mandatory minimum sentences were established for drug offenses and eliminated the difference between drug users and traffickers. As society moved away from a rehabilitative mindset, the hospital closed as a treatment center in 1971 and was transferred to the Bureau of Prisons. It is now a medical center for federal prisoners after serving as a high-security prison for male inmates.

Karibo’s research has led her to congressional hearings and publications produced by patients during their time there. It is aimed at academics who think about mass incarceration and those interested in Texas history. The book will touch on drug treatment, mass incarceration, and how society views addicts, which are today’s hot-button issues as they were in 1929.

When we look at the last 40 years and how society views the current opioid epidemic (medical problem) differently than the crack cocaine epidemic of the 80s and 90s (criminal problem), racial and societal biases still have a long way to go. Karibo is hopeful her research into where the beginning of rehabilitative drug treatment in North Texas can be instructive to those who decide its future.

“Very few people have heard of the farm,” Karibo says. “People are shocked that these institutions existed in the form they were, and it helps us think through some of the questions around treatment today.”

Author