New data released by the city of Dallas and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration reveals that the summer heat is far worse in some pockets of the city, exacerbated by concrete and a lack of shade that can make it feel up to 10 degrees warmer than what the thermometer says.

Last summer was brutally hot. North Texas recorded 47 days of triple-digit temperatures. Dallas ISD warned parents that school buses couldn’t cool down fast enough for their young riders. School districts moved football practices and games around to avoid the heat. Postal worker Eugene Gates died of heat illness in Lakewood while delivering mail.

“I think we had three consecutive days where we hit 109 last summer,” says NBC DFW chief meteorologist Rick Mitchell. “It was just ridiculous, and I don’t know if it’s because I’m getting old, but last summer was just nuts. I started to be the cranky old man.”

Mitchell says we’re paying the price for all the attendant concrete and asphalt that goes with living in a city.

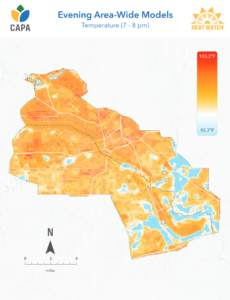

“If you’re in an urban environment, that concrete, all that stuff just absorbs the heat and then gives it back off at night,” he says. “And that’s the whole thing of the urban heat island effect—it manufactures heat from all that stored heat within the concrete and those other surfaces.”

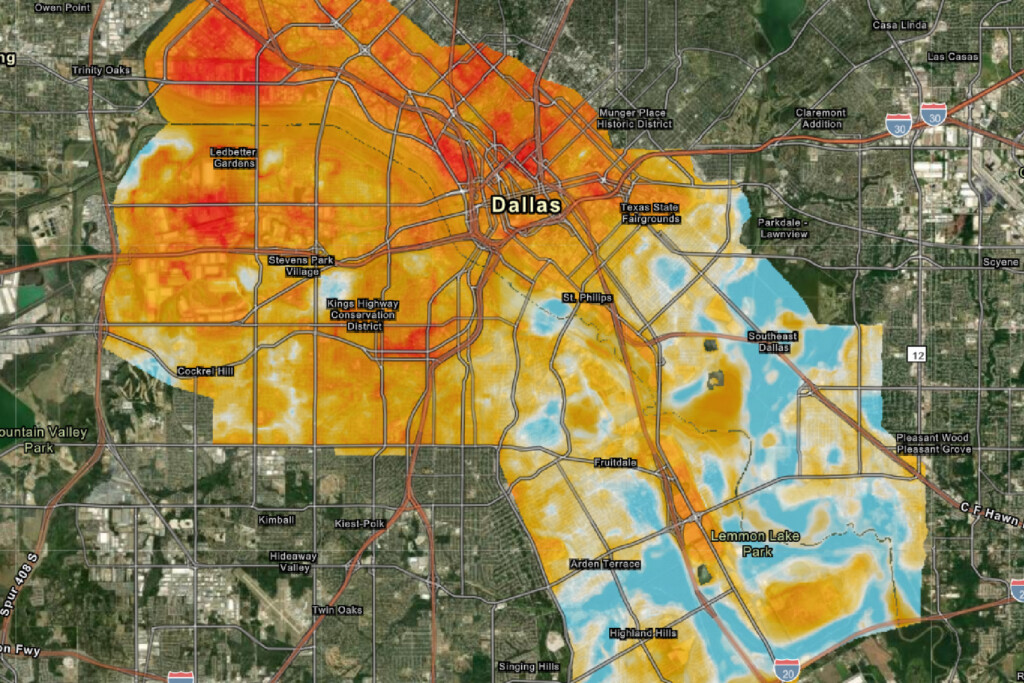

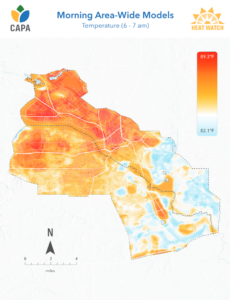

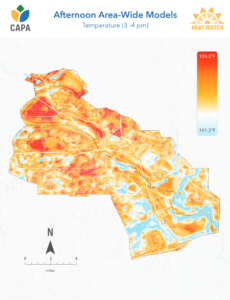

Last summer, the city and the NOAA gathered data to map the city’s heat islands—areas where pavement is more plentiful than trees, which traps the heat. Urban heat islands can be up to 20 degrees hotter than parts of town with more trees and grass. (Dallas was one of 18 cities participating in the 2023 Urban Island Mapping Campaign.)

About 70 volunteers took part in the study during a single day in August. They attached sensors to their cars and drove assigned routes in the morning, afternoon, and evening, collecting 60,000 measurements of ambient temperature and humidity. NOAA then used this data to create maps of the city’s hottest (and coolest) parts. To date, approximately a third of the city has been mapped, with plans to complete the remaining two-thirds this summer.

The city says that the maximum temperature difference between the heat islands mapped last August and the more shaded neighborhoods nearby was 10 degrees. The maximum temperature recorded was 110.1 degrees. The nine routes included areas in West Dallas along Fish Trap Lake, the concrete moat around City Hall, McCommas Bluff landfill, the Dallas Zoo, and the Joppa neighborhood in southeast Dallas.

The mapping identified several heat islands, including Love Field, the Medical District, Uptown, Oak Lawn, downtown, Deep Ellum, the Design District, West Dallas, Bishop Arts, and the Stemmons/Market Center area. All have one thing in common—they’re surrounded by concrete and asphalt. Several are in areas where environmental inequality has existed for decades, including West Dallas and Joppa, whose communities have spent years attempting to remove industrial polluters.

The increased temperatures create a host of heat-related health worries.

“Studying urban heat island is critical to protecting the health of our residents,” Carlos Evans, the city’s Office of Environmental Quality and Sustainability director, said at a news conference about the study’s results. “Health risks from urban heat islands include respiratory illnesses, heat exhaustion, heat stroke, and heat-related deaths.”

“Heat doesn’t really discriminate,” Deputy Mayor Pro Tem Carolyn King Arnold said at that news conference. “What we also understand and even focus on is that when the heat exceeds what is kind of normal heat, it continues to affect our health.”

Julie Hiromoto is a member of the Dallas Environmental Commission. Her day job is director of integration at HKS, where she works on projects that factor in human health, equity, and the environment. She’s also involved with a comprehensive slate of industry groups, including with the Urban Land Institute and Climate Reality Leadership Corps.

Recently, an Environmental Commission subcommittee she chairs met with national and international environmental policy experts. They learned that environmental groups are using heat island data to make a business case for taking climate change seriously. Some of those experts came from the Smart Surfaces Coalition, which has been working with urban cities to change their approaches to cooling down.

“They are doing really interesting research and data gathering right now about how urban heat islands impact commerce and, therefore, tax revenue,” Hiromoto said. “Because people don’t want to walk where it’s hot. People aren’t going to be in a city where it’s hot. They’re not going to be spending money and going to events outside in the community when they’re uncomfortable.

“Anything that we can do to make this the public realm comfortable can translate directly into revenue for local businesses and in an enhanced tax base. They have all the math right behind that to help demonstrate some of that.”

Smart Surfaces is also leading the charge to encourage cities to adopt better street surface options instead of dark, heat-absorbing asphalt. They also encourage local governments to examine which communities bear the brunt of industrial zoning and historical disinvestment.

For instance, when Smart Cities worked with Baltimore, it found that the cost of adopting smarter surface materials and other heat-repelling measures would be about $1.4 billion. However, the city would reap benefits closer to $21 billion over 20 years, thanks to increased jobs, improved summer tourism, and savings in heating and cooling.

But Hiromoto says there are also simpler fixes. Cities need more trees and green spaces. She points to her firm’s next-door neighbor, Pacific Plaza. It was once “a black top surface parking lot that collected all the badness from the cars and pollen” but is now a green, treed area that hosts yoga classes as well as landscaping that attracts pollinators.

“We are very quick to throw a high-tech technology solution at all the bad things,” she said. “If we look at just good design, good healthy habits, and low-tech indigenous natural solutions, it doesn’t have to cost us any more. It doesn’t have to be complicated because the science and all those relationships are already embedded in the ecology.”

Improving the city’s tree canopy is something that the Texas Trees Foundation has been working with the city on for several years. It includes a landscape redesign of the Medical District from along Harry Hines, between Treadway Street and Lucas Drive. Once completed, the corridor will become a linear parkway with a 10-acre park.

“We view our work as investing in trees and people investing in the urban forest so that it can create greener, cooler, healthier communities,” Elissa Izmailyan, the organization’s chief operating officer, said last week. “And investing in people so that they can care for that urban forest and the benefits it provides.”

Evans says that the study’s data will inform all kinds of city policy, from the city’s Comprehensive Environmental & Climate Action Plan to land use and zoning. City Council Member Kathy Stewart, who also chairs the Parks, Trails and the Environment Committee, said that the council will also use the data to better advocate for their districts.

“I pledge to work with council members to find opportunities to expand the green spaces and energy measures to reduce the impact of a heat island effect in their districts,” she said last week.

Dallas has allocated $345.3 million from an upcoming $1.25 billion bond program for parks and recreation. Should voters approve that proposition in May, Dallas will see this money manifest in more public green spaces. The bond includes money to purchase a 20-acre park in the Dallas International District, which is surrounded by a highway, buildings, parking lots, and busy streets. Smaller pocket parks are also planned and will utilize small plots of land that would probably otherwise sit vacant.

A more intentional approach by the city could include implementing greenspaces in areas where asphalt and concrete are unavoidable. Trees and planters could line streets and sidewalks. Airports could include more prairie-type landscaping with native plants.

“Yes, an airport needs to function the way an airport needs to function,” Hiromoto said. “But how about in addition to having the airport, there’s an equal adjacent area surface area, a Texas Prairie or something, that’s offsetting and creating a regenerative approach to that functionality?”

The Environmental Protection Agency says there are also measures homeowners can take to help cool their neighborhoods, including choosing lighter-colored shingles (which can reduce interior temperatures by as much as 3 degrees), planting more trees and native plants in yards, and purchasing energy-efficient appliances. Those measures not only cool down homes, but they also have a butterfly effect of reducing the demand for air conditioning, which reduces demand on the electrical grid.

Mitchell and Hiromoto were quick to say that there is no one “silver bullet” to fix the urban heat island effect. But both felt confident that a mix of low-tech and high-tech solutions could greatly improve matters.

“I don’t think anybody’s just ever gonna sit down and say, ‘this is how we fix this,’” Mitchell said. He’s hopeful that as new research and policy evolves, so will addressing urban heat islands and their impact.

Hiromoto says the benefits of improving the environment in Dallas will bring more than just clean air and cooler temperatures.

“If we were to single-mindedly focus on climate, all the other things are cobenefits of that kind of intentionality. Economic prosperity will follow. Equity will follow. Comfort, air quality, water, all those things,” Hiromoto said. “I think when we think about climate, people see that as ‘saving the planet,’ and it’s not really about saving the planet—the planet is going to be just fine. It’s about saving all of us, and I don’t just mean the humans creating the problem, but all the different species and nature that we depend on for medicine or nourishment or joy.”

Author