Historically, it hasn’t taken much to create a credible oasis in downtown Dallas. The landscape has for decades been defined by a desert of surface parking lots, empty sidewalks, and one-way streets. A lawn, a shaded grove, a pavilion, and a walking path. Some swings. That doesn’t sound like a lot. Though if you catch it at the right time, it can feel idyllic.

That was the impression I got at Pacific Plaza late one weekday afternoon in May. It was lovely by any city’s standards. A family walked its dog by the lawn. A man playing a trumpet sat on a raised block of The Thread, a 611-foot-long limestone wall-slash-bench that snakes through the park. A young woman studied a notebook while sitting on patio furniture near the pavilion, which is ringed by a steel canopy perforated with Morse code. And not a parking space was in sight, an impressive erasure of the location’s recent history as a parking lot by One Dallas Center, with Harwood Street to the east, North St. Paul Street to the west, and Pacific Avenue to the south.

I ambled about, trying to take in every inch of the park’s 3.7 acres. Leaving a paved trail, I followed a muddy unintended path that had been beaten into the grass by who knows how many feet that had preceded mine. In landscape architecture, these game trails made by humans are known poetically as “desire lines.”

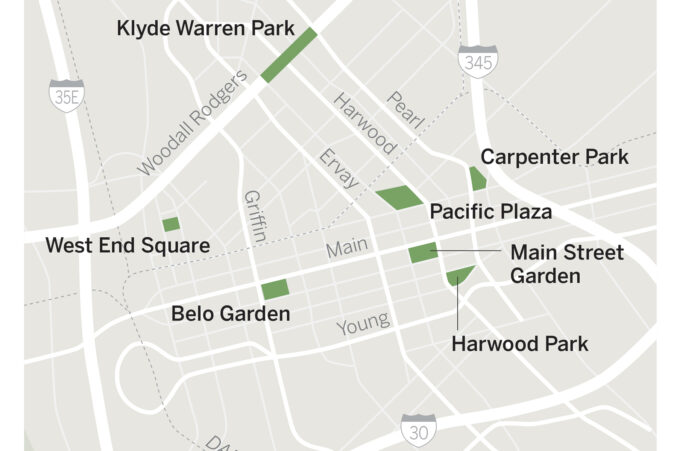

Pacific Plaza is but one piece of a park-building boom that is reshaping downtown.

For that we have Boeing to thank. The aerospace company’s decision more than 20 years ago to scratch Dallas off its relocation shortlist is often cited by downtown boosters as the impetus for the city center’s ongoing transformation from ghost town to, well, city center. That transformation is evident in the rising number of downtown residents, up from about 200 in the 1990s to 12,000 today. You can see it in the money the city pumped into the Arts District and in the investment AT&T has made in its corporate headquarters, where the company recently rolled out its $100 million Discovery District. Perhaps most of all, you can see it in the parks that have sprouted and will continue to sprout throughout downtown.

Klyde Warren Park, which opened in 2012 on a deck built over Woodall Rodgers Freeway, is the improbable (a park over a highway?) hit that in less than 10 years has become one of the most beloved public spaces in the city. Its 5.2 acres are stuffed with regular events like yoga and salsa dancing, a fountain kids can play in, a dog park, food trucks, corporate sponsorships, and a restaurant that was bound to become a Mi Cocina sooner or later. It is the Most Dallas Park Ever. And it’s awesome. You go looking for Klyde Warren Park. You drive the kids all the way from Frisco just to visit Klyde Warren Park. Klyde Warren Park is no oasis. It’s Xanadu. It’s a destination.

That’s not Pacific Plaza. Parks for Downtown Dallas refers to Pacific instead as a “neighborhood park.” It’s one of four such parks the nonprofit foundation is putting downtown. The $15 million Pacific Plaza was the first, opening in 2019. West End Square debuted in March. It cost about $6.25 million and replaced yet another surface parking lot with a plugged-in “smart park” in the West End’s burgeoning Innovation District. Carpenter Park is under construction on the east side of downtown, just down the street from Pacific Plaza, and will include a basketball court and dog park. Work is set to begin on Harwood Park, farther south, toward the Dallas Farmers Market, later this year.

The parks are owned by the city but developed by Parks for Downtown Dallas, which is additionally raising money to pay for their maintenance. Formerly known as the Belo Foundation, the nonprofit was founded by Robert Decherd, the chairman, president, and CEO of A.H. Belo Corporation. (Earlier this year, the parent company of the Dallas Morning News announced its intent to change its name to DallasNews Corporation.) One of its first significant projects was to develop Belo Garden, which opened in 2012 on a site that—you guessed it—used to be a parking lot. The four “priority parks” the foundation has since contracted with the city to build are funded by a mix of public bond money and private donations. Klyde Warren Park, owned by the city but managed and programmed by a separate foundation, is also the result of a public-private partnership.

The similarities end there. Whereas Klyde Warren has become a regional destination, Pacific Plaza and West End Square were designed for their very immediate surroundings, says Amy Meadows, the CEO of Parks for Downtown Dallas. People who live in the high-rises around Pacific Plaza and those who stay at the nearby Sheraton Hotel wanted more green space. So Parks for Downtown Dallas and landscape designers SWA Group gave them a giant lawn and a grove of mature trees, the latter incorporated from a smaller, neglected pocket park that had previously been at the site. Neighboring residents have especially appreciated that lawn during the COVID-19 pandemic, Meadows says, and the general claustrophobia of 2020 drove home how important spaces like Pacific are to downtown.

The three-quarter-acre West End Square is wired with wifi and charging stations, and there are other high-tech fixings that allow for digital art installations. If you visited the park this spring, you may have encountered ANTIBODIES, a sensor-activated video wall that captured and reflected fragmented images of your face back at you. All of which is appropriate for the West End, which has been turning itself into a hub for this kind of “smart city” innovation. Tech firms are headquartered nearby, and you’ll often come across workers with their laptops plugged into outlets on the park’s 50-foot-long table, Meadows says.

Not long after we talked, when I paid a visit to the park myself, I saw just that. There was also a friendly game going on at a pingpong table. Someone was rocking on one of the large porch swings. There’s a small fountain, some winding paths, and greenery. It all segues naturally into the repurposed red-brick warehouses of the historic district, and it’s easy to imagine tourists taking a breather here after stopping at The Dallas World Aquarium or while waiting on a table at Ellen’s.

As pleasant as this all sounds, the early efforts of downtown’s park-building boom have also been met with justified skepticism, some of it published in D Magazine. There is evidence downtown of how easily an oasis can turn into a dump. In 2018, before Pacific Plaza or West End Square had opened, D senior editor Peter Simek compared bustling Klyde Warren with downtown’s relatively glum Belo Garden and Main Street Garden. The latter opened in 2009 near the Statler Hotel. It had a playground and a small deli but no daily programming, no food trucks, and no yoga classes. Almost a decade on, it looked shabby, empty of any signs of life more often than not. Simek questioned whether downtown was ready for the neighborhood park of the sort envisioned by Parks for Downtown Dallas.

“Klyde Warren taught Dallas an important lesson: because the city center itself does not yet have the street life and population to sustain regular old parks, successful parks in Dallas have to be open-air event facilities,” he wrote.

Main Street Garden (which is not a Parks for Downtown Dallas park) has seen daily use pick up in the last couple of years, after the children’s play area was renovated, Meadows says. It was also designed in part as a festival site and has served that purpose admirably when holding events like Homegrown Festival. Other developments near Main Street Garden, like the renovation of the Statler and the UNT Dallas College of Law’s move into the restored old City Hall building, only came after the park itself opened.

There is a chicken-and-egg situation at play here. “The challenge with some of this downtown is waiting for development to catch up,” Meadows says. “If you build the park before the people are around it, you’re going to see it sitting empty much more than if it’s got residents [living nearby].”

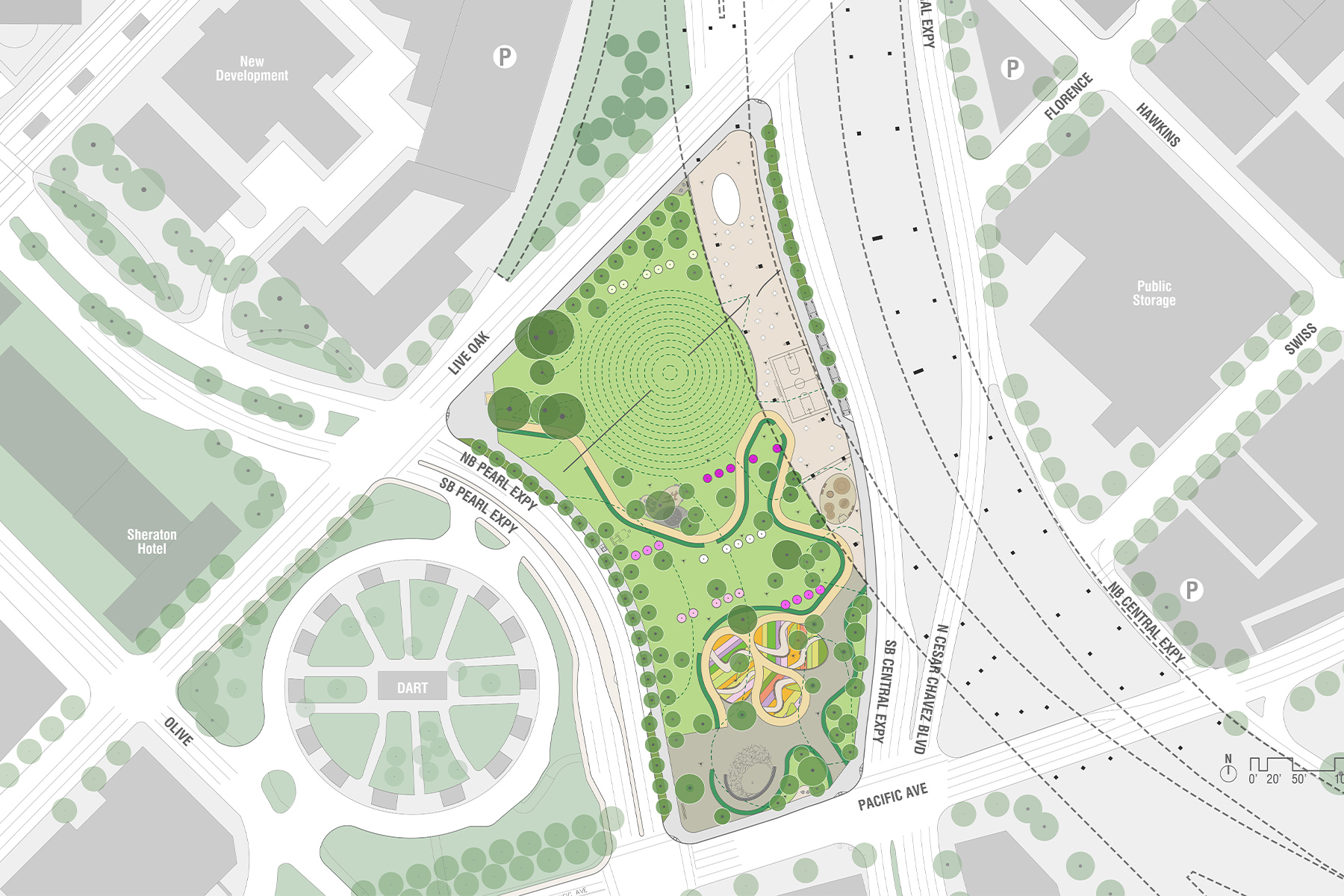

That could be a particular challenge for Carpenter Park. At 5.6 acres, it will be downtown’s largest park. It’s replacing Carpenter Plaza, which had a much smaller footprint and was notable, in those rare cases where it was noted at all, for the presence of the 700-foot-long, 8-foot-tall steel artwork Portal Park Piece (Slice), by sculptor Robert Irwin. The sculpture, restored and retooled, will be integrated into the new park.

Carpenter will also include downtown’s first public outdoor basketball court, as well as gardens and walking paths, a children’s play area and splash pad, and a dog park. A proposed skate park was at least temporarily put on ice because of uncertainty over the future of I-345, the elevated highway that looms to the immediate east of the park. There are tentative (presently unfunded) plans to expand Carpenter either under or over I-345, but they hinge on whether the Texas Department of Transportation decides in the next few years to boulevard, bury, or reinforce the highway that splits downtown from East Dallas and Deep Ellum.

There lies some of the challenge Meadows is talking about. Klyde Warren, as unlikely as its success seemed at its opening, connected downtown and the Arts District to Uptown. Carpenter will be wedged between a DART transfer center to the west and an elevated highway that, in any scenario, will soon undergo major construction. There’s a high-rise going in down the street, near the old Dallas High School building, and more housing on the east side of the highway—although that highway remains an imposing physical barrier even if the park’s planners do see Carpenter as a way to stitch downtown to points east. Are people going to walk their dogs under the highway to go to the park?

The neighborhood parks in downtown’s future aren’t Klyde Warren. You won’t find Pacific Plaza howling with activity around the $10 million “super fountain” shooting water 100 feet into the sky (actually coming soon to Klyde Warren) and the Ford Truck-a-palooza Sustainability Kidz Play Zone (not real, but not impossible). There are no hard metrics to judge whether a park is successful. You want to see people, certainly, whether they’re playing basketball, making faces at a digital art installation, or practicing the trumpet.

Each of these neighborhood parks, even with their more humble amenities, should be able to draw people. Sometimes you want to play basketball. Other times you just want to take the elevator down from your sixth-story apartment and sit on an open lawn. What Pacific Plaza and West End Square can prove is that a successful park can exist downtown without becoming Klyde Warren.

Like the city center, these parks will continue to evolve. They’ll have to. Design plans can’t always tell you what people want, where new desire lines will lead. Meadows likes to say her foundation is building “100-year parks,” designed to last. They’ll still be here—if we get everything else right—as downtown continues to fill with residents and workers who are willing to get out of their cars and spend some time here.

Parks, by themselves, won’t transform downtown into a vibrant core worthy of the country’s ninth-biggest city. But we should take the park over the parking lot every time.

Write to [email protected]. This piece originally ran in the July issue of D Magazine with the title “Downtown Dallas Goes Wild.”