She smiles. “The Sixth Floor Museum wants all this stuff when I die.”

In the 1960s, Nancy Myers, better known as Tammi True, headlined at the Carousel Club, the striptease venue owned by Jack Ruby. Throughout her career as a burlesque dancer, she performed in several downtown Dallas clubs and traveled the country with her routine. They called her Miss Excitement.

Unlike some associates of Ruby’s, Myers remained reclusive, shying from interviews. She gave Esquire an interview decades ago, but felt the magazine misrepresented her. It was not easy to find her. The townhouses in her part of Grand Prairie all look the same. The address numbers are not clearly visible from the cracked street, and the lane in the housing complex weaves in an illogical pattern. Fortunately, she stood outside on her small patch of front yard. As I drove past, our eyes met and I knew it was her. I stopped the car, introduced myself.

A few minutes later, I’m in her living room, digging through the contents of a large plastic bin filled with scrapbooks, old newspapers, playbills, and pocket guides to Dallas entertainment. Inside her house, she has a poodle and a cat she named PITA (“pain in the ass”). A finished newspaper crossword puzzle sits folded in half on her coffee table and nearby on a bookshelf there is a crossword puzzle dictionary. There are framed photos, antiques, numerous plants, and crafted knickknacks. It looks like any grandmother’s home. No one would suspect her former life.

Before she became Tammi True, Myers was married to Cecil Powell. He was a burglar. “Cecil was probably the best safe man in town,” Myers recalls with a sense of pride. “That was fun and exciting, I thought, until I got pregnant.” They divorced when their daughters were 2 and 4. Powell left and took his line of work to California. Myers moved in with her grandmother in Fort Worth.

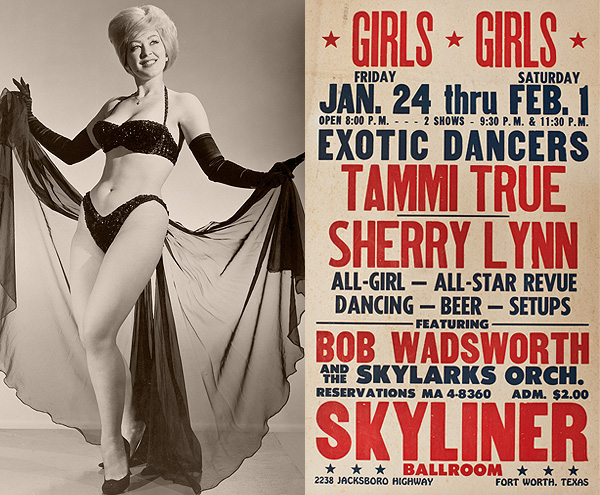

Now single, Myers liked to go out dancing. She met Guy Parnell from Carswell Air Force Base. He had a band. The twist was a popular dance craze, and the band wanted Myers to dance for them. The club that booked them, however, wanted a striptease dancer. Parnell urged Myers to try it. “I said, ‘I cannot do that.’ I was raised Catholic. I was kind of a moral immoral bitch back then. He thought I’d be great, and then they’d book them.” Myers’ friend Elizabeth Klug also encouraged her and offered to make her a dress. “ ‘I’ll make you a costume,’ she said. We bought some green satin and green sequins—a bra, panties, and a short dress. We didn’t know anything about breakaway zippers, so she put hooks and eyes all the way down the side of this little dress that she made.” Jimmy Levens, the owner of the Skyliner Ballroom on Jacksboro Highway, saw her dance. His club did striptease on Friday and Saturday nights. Sherry Lynn, a stripper from Dallas who worked at the Skyliner, offered to train her. Lynn told her to just dance, and then she would cue Myers when to take something off.

“I just couldn’t do it,” Myers says. “They kept pushing me out. I made it. When I got through, she agreed with Jimmy that I had a lot of talent. She took me under her wing.”

Myers danced at the Skyliner on Fridays and Saturdays under the stage name Tammi True. She made $50 for both nights. In contrast, she made $35 a week at her day job. Myers was ready to make her weekend side project a full-time affair.

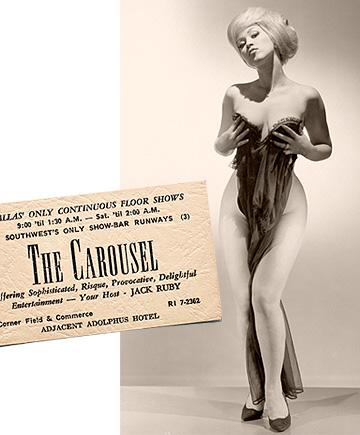

Meanwhile, in Dallas, Jack Ruby struggled with his new Carousel Club. He had owned other clubs with varied levels of failure. The Carousel started as a supper club, but it wasn’t working, so he decided to try it as a striptease venue. Ruby had to get girls, but he didn’t want to go through booking agent Pappy Dolsen. Ruby didn’t like Dolsen.

“Pappy wanted to sign girls up right away, especially new girls, to a two- or three-year contract,” Myers says. “Sherry had already told me. ‘Do not sign with him, because if you do you’ll have to work where he tells you to work and he’ll get 20 percent. He’s got control of you.’ ” Sherry Lynn recommended Myers to Ruby. He hired Myers without even meeting her. “He told me what he’d pay me, and then that he’d give me extra because I’d have to drive from Fort Worth to Dallas and back. And I said okay. I knew him well enough to know what to expect. He was very nice to me. I did my first show, and he was pleased.”

Myers says downtown Dallas looked different back when she was working there. “Downtown used to be vibrant. All the big hotels had a big showroom and a big entertainer.” Several burlesque clubs operated along Commerce and Jackson streets: the Carousel Club, Montmarte Club, the Colony Club, and Theater Lounge, owned by Ruby’s rivals Abe and Barney Weinstein. Across the street from the Carousel, the Adolphus Hotel had a musical comedy revue with a live orchestra called Bottoms Up. The show ran six times a week.

The Carousel Club was open seven days a week. Myers worked from 9 pm to 2 am. The show consisted of four girls, each with her own 15-minute act. There was a band—a trio of drums, horn, and piano—that performed original music composed for each routine. Between the strip acts, the club would feature other entertainers such as a comedian, magician, or ventriloquist—maybe a puppeteer.

Tammi True’s routine had a reputation for being raunchy. “Other girls said I was the dirtiest thing they’d ever seen,” she says. “I could

dance, but I could do it tongue-in-cheek. I learned a long time ago that I was little and cute, and I could get away with stuff other people couldn’t.”

Myers then puts aside the scrapbook. “I’d do a thing where I’d be dancing, lean over, and look through my legs,” she says, standing up from the couch to demonstrate. She turns her back to me, spreads her legs, and tries to bend over. She’s able to bend only at a 45-degree angle. She looks back to me and says, “Can you see the whole show?” I laugh uncomfortably. Myers then turns around. “I’d do a half split.” Myers does not attempt the half split. “I’d fall down into it, and I’d go, ‘Would you say that’s stretching a good thing too far?’ ”

Myers sits down. “When I got up on that stage, I had everyone standing up on their damn feet, hollering, screaming, and hooting. You gotta work the crowd. Fifty percent of it is projection, and the other 50 percent is costuming and talent.”

Her dresses were hand-tailored by Tony Sinclair, a drag queen. “He made costumes for another girl. I really loved her costumes. I met him when I was in Kansas City. They were having a gay convention, and I met him after work. He was being a bitch that night. I asked him about making me some costumes, but he didn’t want to sew.” Myers did not let this stop her. She began to befriend Sinclair. They worked shows together, shared hotel rooms on their travels. Then Sinclair finally relented and sewed costumes for her. “He was right behind the curtain catching all my stuff. He made it and he wanted to take good care of it.” The dresses would cost around $300, which, accounting for inflation, would be more than $2,000 today.

As Tammi True, she was featured in the United Press International news feed for a $150,000 lawsuit against Jimmy Levens. They got into an argument. Levens turned the spotlight off on her at the Skyliner, and a customer pinched her. A lawyer friend convinced her to sue. Myers decided to file a suit “as a lark,” but it never went to trial. When Jack Ruby discovered she was in the news, he was elated. The headlines made her the headliner of his show. “It was worth $150,000 in publicity,” she says.

Myers’ neighbors had no clue about her secret life. During the day, she was a PTA member who baked cookies and helped out with school carnivals. “Our family sat down every day at 4:30 in the afternoon. We didn’t watch TV and eat. We all sat down and discussed our day. Then, I would leave to go to Dallas about 7 o’clock. Of course, I didn’t get home until 3 or 4 in the morning. I would go to bed and get up every day at around 10. So when my children came home, I was up and spent time with them.” Myers stresses this point. The fame was exciting, fulfilling a lifelong desire to be in the spotlight and to be adored. But it all came back to her family. Being Tammi True allowed Myers to buy a house for them, to support her mother and grandmother, and to do it all as a single mother.