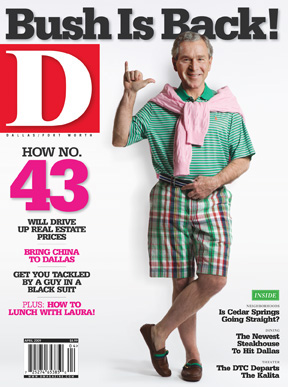

So they’re back. Fifteen years after leaving us for the Texas Governor’s Mansion, Laura and George W. Bush have returned to Dallas. Not since the Jonas Brothers bought a house in Westlake have so many North Texans gossiped about their new neighbors. When the former leader of the free world moves to town, there’s a lot to talk about. In the following pages, five writers explore how the Bushes will affect our lives in Dallas—from why China might be our new BFF to how to survive an encounter with the Secret Service. Let’s be careful out there.

George Bush is Big in Asia

George Bush’s popularity (yes, popularity) could be a boon for Dallas.

by Wick Allison, illustration by Sean McCabe

Considering his low approval ratings, George W. Bush might be expected to be even more low-key than his predecessors. But I would like to argue a different line for the former president to take. While showing proper deference to his successor, he still can have a very positive continuing role where it counts most for the American economy: in India and China.

As it turns out, the former president’s approval ratings abroad are not as low as people might think. In India, Bush is the most popular American president in history. Future historians may look at Iraq as a blip on the screen (an expensive blip, yes, but still a blip) and count the president’s success in courting India as the major foreign policy turnaround of the early 21st century. Because of it, Bush could become one of the most influential and respected ex-presidents in the nation’s history. If he succeeds, Dallas as his operating base will reap many of the benefits.

Bush is not known as a man who indulges in retrospection. So while he suffered many “disappointments” (his word) during his two terms, don’t expect him to dwell on them. He will write the obligatory memoir, but that will be an effort directed at his first priority (after overseeing the fundraising of his presidential library at SMU): repairing his own family’s fortunes. The sale of the Texas Rangers brought him an after-tax return of about $12 million, which no doubt increased substantially in the bull markets during his time in public service. But there’s also little doubt that he, like everybody else, has seen those gains disappear in the market collapse. To begin the repair program, he gave his first post-presidential speech in Calgary in mid-March, probably netting him an easy $150,000, and there’s little doubt more will follow. Even so, Bush is likely to be considerably more circumspect than Bill Clinton in this regard (as in others). The Clintons have reportedly amassed a $100 million fortune since leaving office.

America’s preeminence in the post-Cold War era and its dominance of the global economy have given ex-presidents a prestige abroad that Americans at home cannot really grasp. Bill Clinton has not been shy about using it, which is why so many governments and sovereign funds are donors to his foundation. While Bush is not likely to follow Clinton’s lead in grasping after every available dollar, he could not ask for a better model in forging his post-presidential identity.

Like Jimmy Carter, Clinton established a nonprofit foundation, named it after himself, and began leveraging his name to do good works. His HIV/AIDS initiative—an issue Bush cares deeply about—has provided free, life-saving medicine to 1.4 million people, mostly in Africa. His climate initiative is working with 40 of the world’s largest cities to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. His foundation is now tackling childhood obesity.

Bush is in a position to do more than promote good causes, important as that is. His strength is in Asia, and he should use Bill Clinton’s model to leverage it.

China, of course, does not encourage public opinion polls. But a recent Los Angeles Times story found indications of affection for Bush everywhere, especially in Beijing, where his image dominates an exhibit hall in the Cultural Palace of Nationalities. Bush extended a hand to China immediately after 9/11 and backed it up with free-trade policies that enabled China to become the third-largest economy in the world. He sealed the deal by attending the 2008 Summer Olympics in the face of criticism over China’s human rights record. No one action could have been more important to the face-conscious, still-insecure Chinese. The Times quotes a retired nuclear scientist: “We will never forget that the leader of the most developed country in the world stood up to pressure to come to the Olympics.”

India, on the other hand, depends little on exports. Its is a service economy. While India, too, has been hit by the global meltdown, growth is only expected to fall to 7 percent from 9 percent last year. (A report by the Federal Reserve of Dallas last August predicted that India’s economic growth would be more resilient because of its mix, and so it has proven to be.)

In the world’s largest democracy and now fastest-growing economy, we have tangible proof of Bush’s popularity. During his time in office, polls in India routinely gave him approval ratings in the high 50s up to the low 70s, even while Indians expressed disapproval of such policy decisions as the Iraq War.

To understand why Bush is so popular, we have to understand a little about India’s recent history. After independence in 1947, India kept three vestiges of its colonial past, one that would serve it very poorly and two that would serve it very well. The first was a state-managed economy, brought to India by English graduates of the London School of Economics and maintained by Indian graduates of the London School of Economics. We know how well that worked. The second vestige, which worked considerably better, was the British educational system. The third was, as every educated Indian’s second tongue, the English language.

Anti-colonialism and a socialist ideology in the first 50 years of the new country’s independence tilted India toward the Soviet Union. In response, American policy makers adopted Pakistan as our proxy in the region, which only pushed India further into Moscow’s open arms. As the Cold War heated up, India became perhaps the most anti-Western country in the world not directly under Soviet or Maoist control.

The Soviet Union was India’s largest trading partner, and when it collapsed, one or two Indian states—which have a great deal of autonomy in the Indian federal system—started gingerly experimenting with loosening business regulation, encouraging entrepreneurship, and allowing free trade. The experiments were so successful that even the orthodox socialists in New Delhi had to wake up. Even so, Indian hostility was so deeply ingrained that, three years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Tom Clancy could write a best-selling novel envisioning a scenario in which India would ally with a Japanese business cartel to take down the United States in the Pacific.

With three moves, Bush reversed this decades-old antipathy. First, in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, he threw the Taliban out of Afghanistan, removing an Islamicist putsch in a nation long friendly with India. Second, he abolished restrictions on India’s access to civilian nuclear technology and nuclear fuel, which was viewed as sign of India’s maturity as a world power. Third, he visited India in 2006 to establish new bilateral relations, a personal touch that was welcomed as a sign of America’s new respect for India’s emergence in the world economy. Meanwhile, the Bush presidency coincided with the rapid rise of outsourcing by American companies, which fueled enormous employment growth in India.

For his willingness to embrace this recalcitrant emerging power and overturn a half-century of American policy toward the subcontinent, Bush is regarded, if not as the father, at least as the rich uncle of the Indian economic miracle.

The former president could do no greater service to his country than to continue to build on the foundation he laid in Indo-American and Sino-American relations. The Bush library complex will include a policy institute that, I hope, will focus on his most notable foreign policy success, the new bilateral relationship with India. By bringing together Asian and American policy elders, business leaders, and opinion leaders, the institute could continue the work he began. Under the president’s leadership, the Bush institute has the opportunity to become the place where conversations between the world’s two fastest-growing economies and the world’s largest economy take place and where bilateral policy questions can be addressed in a less formal, more collegial, and more creative environment than allowed by diplomacy through official channels.

The high regard for Bush in Asia could be a major asset as Dallas becomes an international player. Dallas already has a direct stake in the success of the major Asian economies. China’s shipping containers are unloaded at the Port of Long Beach onto railway cars headed to the Dallas Inland Port for breakup and delivery across the country. Major Dallas employers such as Texas Instruments, Kimberly-Clark, Hewlett-Packard’s service division (formerly EDS), AT&T, and Verizon have made major investments in China and India. Dallas already is blessed with vibrant and prosperous Chinese and Indian communities. (The Chinese have a Dallas daily newspaper; Indians here have their own glossy monthly magazine.)

With social and business connections already so well established in Dallas, the Bush institute is perfectly positioned to strengthen the intellectual and public policy connections that smooth the way for friendly relations and increased trade. That would be a lasting legacy—for George W. Bush, for Asia, for America, and for Dallas.

Write to [email protected].

This article has been revised to reflect the following correction:

Correction: April 15, 2009

We stated in our story “He’s Big in Asia” that “Ross Perot’s companies have more employees in India than in the United States.” Of Perot Systems’ 23,000-plus employees working across the globe, 65 percent are based in the United States.