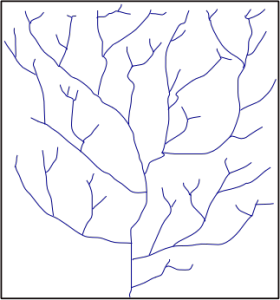

In a recent post regarding modern transportation planning versus, say, natural, organic city building, I wrote that the dendritic networks planned and built exert a diametrically opposite force on the real estate market than does a more interconnected grid. The first question is, what is dendritic?

Below is a diagram of a dendritic system, often used to describe watersheds. With regards to street networks it is a convenient way to categorize a hierarchy of streets in a branching out pattern. Local roads feed Connectors which feed Arterials which then in turn feed highways, the central “trunks” of the system, so to speak.

As you can notice by the diagram above pick any two various points and they won’t be as well interconnected as say, a true grid:

But the fascinating thing about these two separate ways of building the “bones” of a city for which land use provides the flesh, is the diametrically opposite force exerted upon the real estate market. The transpo network, the connectivity, is the first order system applied to a place. The “body” or the physical city of uses and buildings is the emergent second order network that is entirely dependent upon the degree of connectivity at the order below.

The rigidly hierarchical dendritic pattern is indicative of a flat or spread out “market.” No place is really any more or less interconnected than other places (thus why studies like intersection density and space syntax are valuable — they measure interconnectedness). In cities, the degree to which you are connected to persons, places, and things determines the value of that particular site. The higher the value, the greater the demand, opportunity, and therefore density. Because the hierarchical 1st order system produces little hierarchy in the 2nd order system, it suggests an outward or centrifugal force, or outward pressure, on the real estate market. All places are equitable. Evenly and poorly interconnected. And the result is sprawl. Demand smeared evenly across the entire landscape.

The grid, though it seems “democratic” in that all blocks are treated differently has its own built in hierarchy, which is functionally “nested” within the grid. Think of the black lines above being streets and blocks, with buildings within. The usable spaces become increasingly private as you move further inward within those blocks, from street to building entry to corridor to room, etc., each nested further within it. These is a common characteristic within all complex systems.

Side note: the grid can be more complex or radial, as long as it is highly interconnected, ie “reticulated,” in that there are multiple routes between various points.

Because the hierarchy inherent in reticulated systems only appears at the next level of complexity and order, it can be said that reticulated grids exert centripetal force on the real estate market or convergent. There is greater value at intersections and hubs of networks because they are more interconnected. How we value the availability and amount of the possible interconnections between people, places, and things drives city form by driving demand, and in turn density. Inward.

Let’s examine it mathematically…

The reason is because (and this is before we get into the local/global hierarchy, which amplifies certain locations, ie hubs within hubs into infinitely complex networks upon networks) different parts of the grid are more interconnected than other parts.

If we take the basic grid for time/simplicity’s sake, and put a semi-transparent (10%) circle upon every intersection (call it a neighborhood), we get the following diagram. Each neighborhood would consist of the same amount of people, places, and things. Each is equal. Yet as you can see when overlaid to the entire system, another level of order appears, a gradient with the greatest “density” at the center.