As the pandemic got underway in earnest, in March 2020, Corey Anderson found himself 7,500 miles from home and a world away from the fame he’d known for much of his life. Back in Auckland, Anderson’s was a household name. He’d been a star on the New Zealand national cricket team ever since he’d set a world record for the fastest player to score 100 runs—a “century,” in cricket parlance—in a one-day match at just 21 years old. He’d spent the better part of a decade as a globe-trotting superstar, a hulking 6-foot-1, with the blond stubble and effortlessly tousled hair to pass for the Hemsworth brothers’ Kiwi cousin. He’d grown accustomed to being cheered on by tens of thousands from Mumbai to Barbados and, at his peak, pocketing more than half a million dollars for two months of work in the Indian Premier League, the world’s biggest and most lucrative franchised cricket competition.

Then, just days before worldwide air traffic was grounded, Anderson flew from Auckland to Dallas, where his live-in American fiancée, Mary Margaret, was already visiting her mother in Highland Park. For the next nine months, he’d be cooped up in the guest room of his future mother-in-law’s house, acclimating to a life away from the game, stranded in a place where, he says, “cricket’s basically irrelevant for 99 percent of the country.”

A part of him had been preparing for such a transition ever since he got serious with Mary Margaret, whom he’d met at a party four years earlier while on vacation in Croatia. During their courtship, he’d visited Dallas often enough to imagine a life for himself here, growing so fond of the city—the flat terrain, friendly people, and tree-lined streets reminded him of his hometown of Christchurch—that it came to feel like “home away from home.” But that was supposed to be well into the future, after his playing days ended. He’d turned 30 only a few months earlier; he imagined five, maybe six, more years of top-class cricket in front of him. And there was none of that to be found in Dallas—or anywhere else in the United States.

“I knew in my head that I was going to move here at some point in time,” he says. “It just wasn’t yet.”

In the meantime, though, the borders were closed. He was stuck, with nowhere to play. So he may as well be of use. About six weeks after arriving in Dallas, he tracked down the phone number of Iain Higgins, then the chief executive of USA Cricket, and asked him two questions: what is the state of American cricket, and is there a way he could help?

The answer to the latter question, as it turned out, was he could. For 90 minutes, Higgins laid out a plan that, if successful, would change professional sports. As cricket surged to become the world’s second-most popular sport, the United States remained by far the largest market it had yet to penetrate, though not for lack of trying. In 2004, a domestic league called Pro Cricket lasted all of a season. A half-decade later, the American Premiere League was announced. It would take a dozen years, and the collapse of the governing body that sanctioned it, for any games to be played, at a far smaller scale than envisioned. But the national interest is there. Peter Della Penna, who covers the sport for ESPN’s English-language cricket site, says that the United States is neck and neck with the United Kingdom as the country providing the most web traffic, behind India. The domestic club scene is growing, too. One-off tournaments dot the country. But no one had ever blended fiscal might with the necessary cricket smarts to build a competition on par with the biggest franchised leagues in India, Pakistan, England, Australia, and the Caribbean.

Until now. Higgins told Anderson about an investment supergroup called American Cricket Enterprises, which had formed to create Major League Cricket, a six-team professional league that intended to succeed where everyone else had failed in the States. Four of the teams are backed by Indian Premier League clubs, who transformed cricket from stuffy to spectacle at a level unmatched by anyone else. Games would be played in July, a dead spot on the global cricket schedule, as well as the most wide-open time of year on the American sports calendar. There would be world-class stadiums, youth academies, and an accompanying minor league.

And, oh, there was money—$120 million to be exact, after $44 million raised from Series A and A1 rounds plus $76 million in additional investment from the likes of Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella, who co-owns Major League Cricket’s Seattle Orcas, and Ross Perot Jr. and Anurag Jain, who are part of the ownership group of Texas Super Kings, the North Texas franchise. More than enough to lure premium talent across the Atlantic for a few weeks per year or persuade them to relocate full time in hopes of establishing a cricket culture that would help elevate the United States into a powerhouse. Do this right, and one day Major League Cricket could bully its way into the top handful of leagues in the world.

That is where Anderson came in. The following night, Major League Cricket co-founder Sameer Mehta delivered a proposal. What if Anderson accelerated his plan to relocate to the United States? Doing so would come at considerable cost. It would mean renouncing his eligibility for the New Zealand national team and changing residency to the United States, a three-year process that limited the number of days he could leave the country. Anderson’s earning potential would be slashed, too, at least as long as he had no international matches to play and a smaller window to compete in franchised competitions across the globe. He’d face long odds to compete on stages smaller than the ones he’d already graced.

But saying yes would give him a chance to matter in a way he never could as a cricketer alone. Anderson’s record for the fastest century had fallen a year after he’d set it. He would soon be replaced on the New Zealand team. “But if this can turn into what I think it could turn into, the legacy you create is way bigger,” he says. “Leaving a footprint on the game of cricket [instead of] just being a player who played the game and left the game.”

Best of all, Anderson was already right where he needed to be. While Major League Cricket teams will eventually play in their home cities, which also include New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle, and Washington, D.C., only North Texas has a stadium that would be competition-ready out of the gate. For at least the first two years, the bulk of Major League Cricket matches will be played out of the newly renamed Grand Prairie Stadium. (A portion of this year’s games will also be played in Raleigh.) So, too, will a handful of matches in the 2024 T20 World Cup, which the United States will co-host with the West Indies. Perhaps even a match or two in the 2028 Olympics, which is considering adding cricket as a sport. Major League Cricket plans to install its headquarters in Grand Prairie Stadium, where its Australian physical performance coach, Burt Cockley, already resides with the intention of working out of the high-performance center scheduled to be completed next year. Players, drawn to the cheaper cost of living, plus being at the new hub of American cricket, are following. Setting down roots in Dallas would not only amount to a ticket home for Mary Margaret, who had moved to Auckland almost three years earlier, but it would also place Anderson at the epicenter of the most audacious American sports experiment since Major League Soccer was formed in 1993.

So Anderson signed on—and once he did, says Cockley, “it kind of showed this thing was real.” Now, three years later, Anderson will take the field as part of the San Francisco Unicorns, who selected him fourth in the league’s inaugural domestic player draft. In August, he’ll again captain the Dallas Mustangs, one of 26 teams in Minor League Cricket. He has become one of the league’s brightest faces and trusted ambassadors, and he remains steadfast in his optimism. As Anderson recalls telling Liam Plunkett, an ex-England international he helped recruit to the league, “This is kind of like being part of a startup. Do you want to get in now? Or would you want to wait three or four years and then go, ‘Damn, this thing took off. I’m now joining a bigger crowd to try and kind of find my way’? ”

But startups bust far more than they boom, and that’s especially true for startup professional sports leagues. Generations of suits have tried and failed to establish lucrative counterprogramming to Major League Baseball, from arena football to rugby. And none of them faced a challenge quite like Major League Cricket’s: to yank a sport buried in the American subculture into the mainstream, while it also attempts to reorganize how the game is played at the grassroots level.

All the necessary capital—financial, intellectual, athletic—is in place, which only heightens the urgency. Never before has this level of investment been poured into American cricket, which might make Major League Cricket the last, best chance for the sport to hit it big in the United States.

“If this doesn’t work, it won’t work,” Cockley says.

North Texas will be the proving ground.

Cricket is coming to North Texas for all the reasons you might guess. The centrally convenient location. The top-five media market. The thriving sports scene. Even the demographics. Della Penna characterizes cricket in America as “99.9 percent” Southeast Asian or West Indian expats; regional populations have ticked upward since the dot-com boom and surged over the last decade.

But Major League Cricket planted its flag here for one reason above all others: there was an empty shell for it to crawl into, to call home until it could, hopefully, someday, outgrow it. Consider Major League Cricket a sports-league hermit crab.

AirHogs Stadium, across the road from Lone Star Park, has been vacant for three years. The independent-league baseball team it was named after played there from 2008 through 2020, but, toward the end, they were lucky to draw 1,700 fans in a night. After the Texas AirHogs went bust in 2020, Major League Cricket saw its opening.

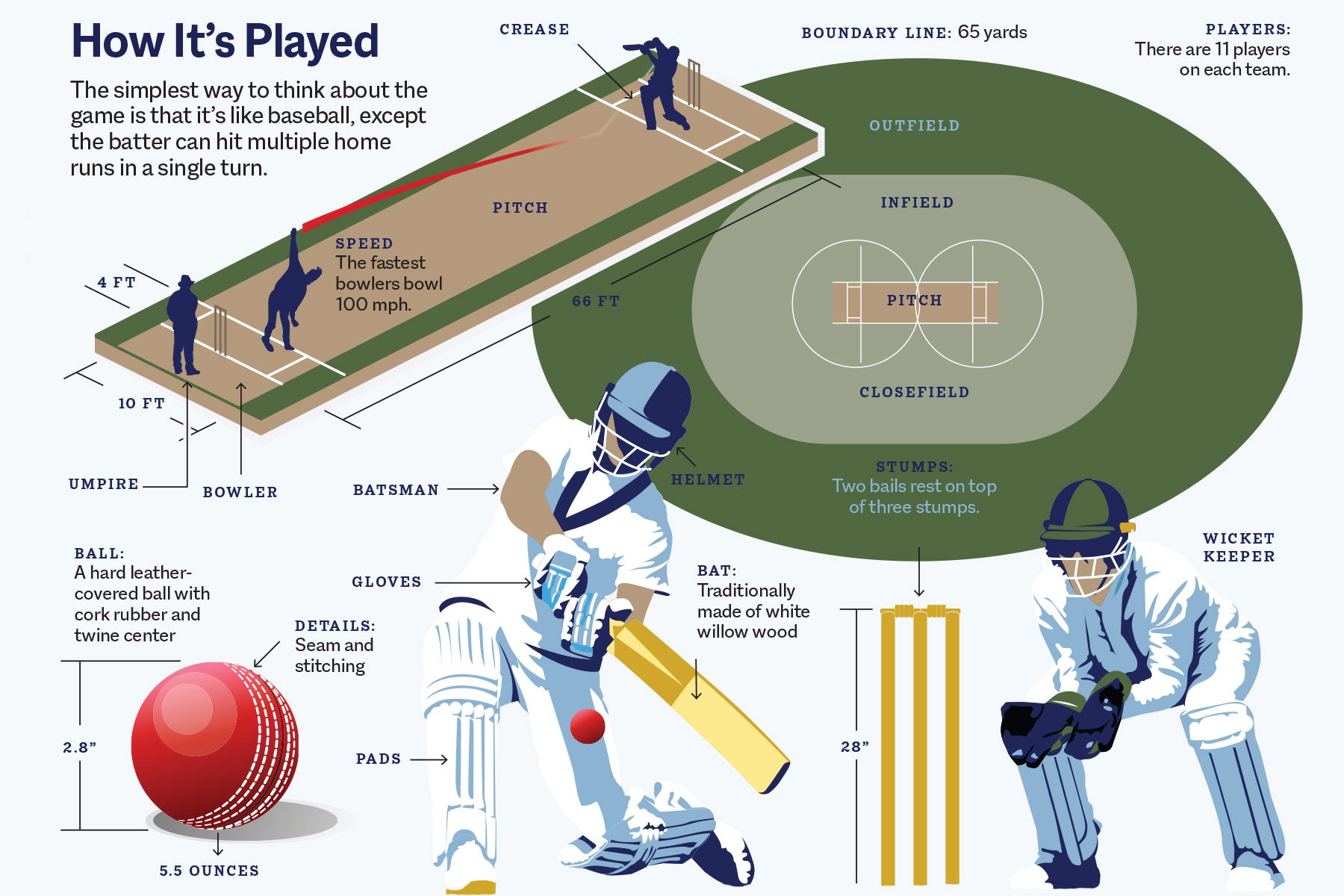

Perhaps Major League Cricket’s greatest impediment toward growing the game will be getting Americans to play it. The ideological challenge—how do we get people to care about our sport?—is no different from the struggle Major League Soccer faced 30 years ago, or the one Major League Rugby, which was founded in 2017, weathers today. Of course, cricket’s idiosyncrasies can be more complicated than those in soccer or rugby; a wicket, for instance, can refer to either the pitch the sport is played on or to a key piece of equipment on that field of play.

Logistically, however, cricket’s plight is unique. The sport is intended to be played on dedicated turf wickets, not grass, which precludes it from sharing space with most of the courts, fields, and diamonds this country has built over generations. Unlike soccer pre-MLS, cricket isn’t played in American schools, which removes a crucial avenue for exposing young people to the sport and rules out the scholarship incentives that keep so many athletes (and their families) invested. That flattens the player base and thus the demand for school districts or parks and recreation departments to build those turf wickets where a grass field is cheaper and more widely used, to say nothing of bargaining power that nudges change along. As a result, most games around the country are played on concrete, a poor substitute for turf, given that the ball bounces more frequently and more predictably. The lack of proper turf wickets means the average American is not even playing the same sport as the rest of the world.

“I had absolutely no idea what I was coming into,” says Andries Gous, a 29-year-old South African who signed on shortly after Anderson did and will play for the Washington Freedom. “I had no idea that the infrastructure was so far behind.”

So it should come as little surprise to learn that Major League Cricket’s six markets, with a combined population of 55.2 million people across their metropolitan areas, had zero existing venues suitable for high-level cricket. Building them all from the ground up would take years Major League Cricket didn’t have if it intended to be ready for 2023. But if it could create even one, the operation would have legs.

That made the shell of AirHogs Stadium quite appealing. First, repurposing the old stadium would generate far less red tape than constructing a new one from scratch. Better still, according to William Swann, Major League Cricket’s vice president of corporate development and infrastructure, using the old stadium cut the cost in half.

There was just the matter of overhauling it. For that, Major League Cricket turned to HKS and project leads Sergio Chavez and Greg Whittemore—an unusual challenge for the latter, a self-described football guy and soccer fan. “We didn’t grow up playing cricket,” Whittemore says, “and it’s been quite an education for us.”

To catch up, they mined what they could from their surroundings, from picking the brains of U.K.- and India-based colleagues to the lessons learned from the multiuse cricket-rugby stadium HKS designed in Perth, Australia. Then Whittemore and Chavez got to tinkering. They commissioned months-long studies to determine the correct rotation of the wickets to minimize glare when players switched sides. They designed a new lighting system to replicate the effect during night matches. Out went the old seating bowl and the kitschy outfield swimming pool. In came a moving screen positioned deep behind the bowler to replicate a batter’s eye in baseball. Capacity was adjusted to 7,221, with room to expand and accommodate thousands more for big events such as the World Cup. AirHogs Stadium became Grand Prairie Stadium, the temple of American cricket.

Not all the baseball touches are gone, however. “We’re going to have—I constantly say this—the world’s only cricket ground in a baseball stadium,” says Major League Cricket tournament director Justin Geale. “It’s going to be a meeting of the worlds. It’s not ideally perfect in terms of sightlines and things like that for cricket. But it’s going to be a uniquely American cricket ground and experience.”

If that reads like boosterism, that’s the point. Because if there’s one thing everyone associated with Major League Cricket—brass, players, fans, media—agrees on, it’s that high-level cricket alone won’t sufficiently capture public interest. It must be American cricket, a blank slate of a term that Anderson believes is “going to be the biggest struggle” to define.

As for what passes for American cricket in 2023, according to Della Penna, “it’s basically adult males who grew up with cricket [overseas], are wildly passionate about it, and they’re trying to sustain that passion, that love, living in America, and that’s driven the quote-unquote growth and the quote-unquote investment in the cricket communities.” The problem is, that hasn’t come hand-in-hand with a grassroots setup capable of carrying that passion outside of their communities. The sport remains too insular to encompass much of the country it’s trying to represent.

Slowly, this is evolving. Asif Mujtaba settled in Plano in 2006, after a long career with the Pakistani national cricket team, where he briefly served as vice captain. In 2011, he was recruited to start the Dallas Youth Cricket League, one of the dominant youth organizations in the region. Back then, he estimates, maybe 100 kids were playing cricket in North Texas. Now he puts the number at around 1,000—a big spike, but also a pittance compared to soccer, let alone more entrenched sports such as football, basketball, and baseball. Major League Cricket can solve for some of this. It is ramping up efforts to install hybrid wickets—part clay, part synthetic grass—around the country to improve playing conditions. There are 30 league-affiliated academies around the country, a number that figures to grow once Major League Cricket delivers proof of concept that it can polish unproven talents into batsmen ready for the big stage.

“All the parents want this game to grow and [to know] that my kid has a future in the sport,” Cockley says. “There’s a system, there’s a pathway, and they’re just not a number in an academy paying $300 a month with no future.”

What the league can’t address on its own is the need to go exponentially broader, both in numbers and diversity. For instance, women simply don’t play the sport. In its most recent annual general meeting in October, USA Cricket claimed a national total of 283 registered female players.

There’s also the matter of that microscopic 0.1 percent of players outside the Southeast Asian community.

“The lazy argument that always gets made is ‘You say you want American, you just mean you want White people playing,’ ” says Della Penna. “Forget about White people. Are you going to find anybody who’s Black, or Mexican American, or Japanese American, whatever? Are they going to be playing? No.”

The solution may require a moment more than it does a road map, which is where the United States national team comes in. While Americans may be new to cricket, they’ve got a century’s worth of experience tuning in to support their country in international competition and making heroes out of the victors. Imagine if North Texans get a front-row seat in Grand Prairie to a Cinderella run from the Americans at next year’s World Cup. Better still, imagine that same scenario playing out at the Olympics in five years, when the United States stands to have a much deeper roster if Major League Cricket continues to buttress the domestic talent pool.

“If somehow, gods help us, we win a medal, all of a sudden you’re sitting at The Tonight Show,” says Lovkesh Kalia, who emigrated from India to Dallas in 1989 and now owns the Dallas Mustangs, the Minor League Cricket team that Anderson captains. Then the dam bursts: more awareness, more stars, more fans, more lobbying power for cricket to get in schools and carve out dedicated spaces in public parks. “It won’t be just the Indians or Pakistanis going out there and asking for something,” he says. “It’d be the overall public asking for something, like it’s happening in soccer.”

All of that is bigger than Major League Cricket. It also depends on USA Cricket—an organization historically long on turmoil and short on funds—finding stable footing. It requires USA Cricket, which knows the lay of the land, seeing eye to eye with Major League Cricket, which has achieved so many things their American counterparts never have. All of that is independent of the other checkpoints, like the other five Major League Cricket organizations getting stadiums in their own cities, or those organizations cultivating fan bases patient enough to endure their teams possibly spending the next several summers in North Texas before they ever play a match at home.

“It’s a long way to go,” says Mujtaba, the Pakistani international turned youth coach, “and it takes a lot of years.”

But just as startups fail more often than they succeed, venture capitalists, as a rule, hunt growth and profits. And while finally cracking the American cricket market remains the upside play, the low-hanging fruit for an organization deeply in business with the Indian Premier League is selling a lucrative overseas rights package to the gargantuan Indian market, with its seemingly boundless appetite for world-class cricket. Far more durable cricket scenes have succumbed to that economic pressure. The Caribbean Premier League, one of the world’s most vibrant franchised leagues, aligns half of its playing schedule with prime-time viewing hours in India. What happens if Major League Cricket, with only one local fanbase to cull from out of the gate, can’t even attract the requisite 7,000 spectators to fill Grand Prairie Stadium? What if it does, only to then go the way of the Caribbean Premier League when it staged neutral-site games over a three-year period in Fort Lauderdale? They drew 10,000 people initially and then plummeted to as low as triple-digit numbers by the end.

“If that’s the route they want to go, then, you know, good luck establishing and embedding yourself in the community and making people in Texas actually care,” Della Penna says. “And then all the talk and all the philosophy about, ‘Oh, we really want to become part of the Texas community. We really want to make this really big in America’—that’s all nonsense.”

It would make Major League Cricket a global financial success but an American cultural failure. And the longer it takes for the league to achieve a foothold domestically, the more likely it seems that the money behind the effort will look for a short-term payoff over long-term impact.

“Eventually, you’re going to have to make a decision,” Gous says. “That’s why it’s so important to get the American market into it. Otherwise, it’s going to happen.”

Until a few months ago, the great hope of American cricket was just another lanky college junior studying accounting at UTD’s Richardson campus. Twenty-year-old Ali Sheikh was preparing for a dependable office job after graduation. What was the sense in getting starry-eyed about cricket, his passion since he was a child in Doha, Qatar?

For the longest time, it didn’t matter that a global star like Mujtaba, his coach, spotted his talent at 13 years old in their first workout together. Or that Sheikh has gone on to captain the United States under-19 team. Or that a professional like Gous regarded him as “probably the best [player] under 23 in this country,” with his combination of slick fielding and endurance honed during a varsity soccer career at Lebanon Trail High School in Frisco. Cricket in America is a hobby, not a life.

Then Major League Cricket came along. After a standout performance at the league’s pre-draft combine, Sheikh found himself in Houston for the inaugural draft, where, for what felt like hours, he sat and clapped politely, secure in the knowledge that no one would be calling his name as the draft shifted into the sixth round.

“And then I hear [the announcer] go, ‘Ali Sheikh,’ ” he says, “and I’m like, Hold on, that’s me.”

Suddenly there he was, shaking hands on a stage and donning the cap of his new team, the Los Angeles Knight Riders. He is no longer just another accounting major walking the campus at UTD. “People at school know me as ‘the cricket guy,’ ” he says, almost bashfully.

Between the local scene, Minor League Cricket (he’s a teammate of Anderson’s on the Dallas Mustangs), and now Major League Cricket, he’s making real money in the sport. His parents are encouraging him to take a gap year to focus on his game.

“At the start, I felt like it couldn’t be a full-time job,” he says. “Now I feel like it could easily be a full-time job.”

Major League Cricket is counting on exactly that. If the league reaches its potential as a cultural force in America, it won’t be on the backs of players like Corey Anderson, vital as he is. It will happen because it minted a generation of American-born stars to rise through the ranks and stake their claim as faces of both the league and the United States national team, creating competition and representation along the way.

“We need,” says Geale, the Major League Cricket tournament director, “literally another 10 Ali Sheikhs.”

And why couldn’t it happen? For all Sheikh’s gifts and drive, Cockley, who has worked with him since Sheikh was 16, is quick to note that “he also benefited from being in the right time in history.” A time when the American cricketer suddenly has an endgame to aspire to and a pathway to achieve it. When in North Texas, especially, they’ll be surrounded by sharp minds and blossoming infrastructure and world-class talent to test their skills.

Sheikh has yet to play a match at Grand Prairie Stadium, but as Mujtaba says, “for the young people, he is an inspiration.” There is finally something, someone, to aspire to.

Which is why Major League Cricket’s first significant victory didn’t take place in a boardroom or with a player recruitment or during a groundbreaking ceremony, but on a phone conversation a few days after the Major League Cricket draft, between Kalia’s nephew, Bhavesh, and one of the Mustangs’ next stars, 17-year-old Rishi Ramesh. “I’m gonna get serious about cricket now,” Ramesh told the younger Kalia, so much so that, when it comes time for college, he’s considering online classes at UTD to give him the flexibility needed to train and compete.

Ramesh has a goal in mind, and if Major League Cricket’s vision takes root, he’ll be far from the only one. He doesn’t want to become an accountant.

“I want to be the next Ali Sheikh,” he said.

This story originally appeared in the July issue of D Magazine with the headline, “Batter Up.” Write to [email protected].

Author