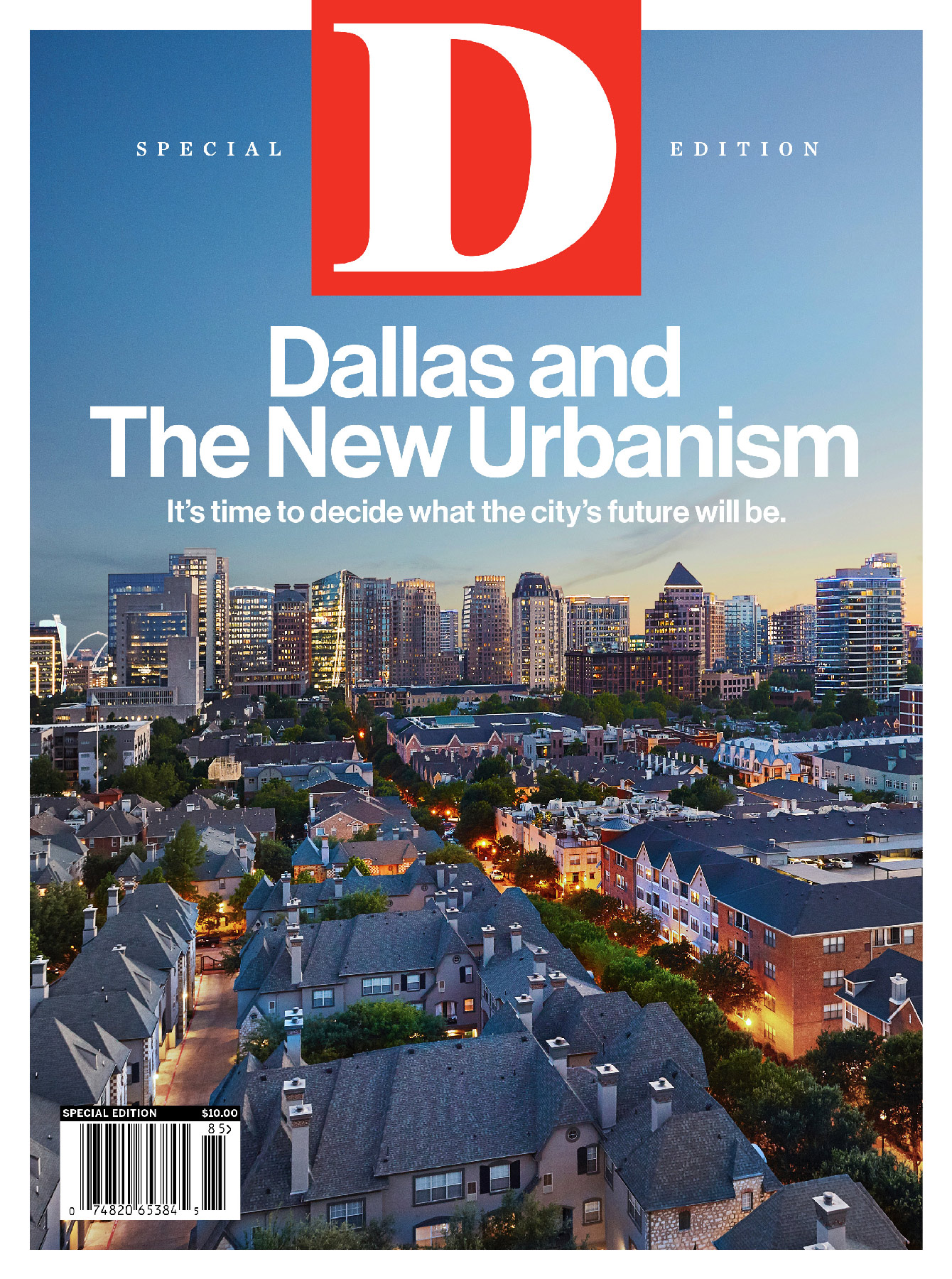

This piece is a feature from our special edition, Dallas and The New Urbanism. The magazine examines the successes and pitfalls of the urbanist movement in a region well known for its dependence on the automobile.

This piece is a feature from our special edition, Dallas and The New Urbanism. The magazine examines the successes and pitfalls of the urbanist movement in a region well known for its dependence on the automobile.You often hear two things about growth in the southern sector of Dallas. One, typically from southern sector residents and leaders: as soon as they get a 7-Eleven or a Starbucks, then they’ll have made it. The other, typically from residents north of I-30: southern Dallas needs a Mockingbird Station.

Both of these notions are misguided. Large chains base their decisions on sophisticated algorithms that determine the “dollar density,” or buying power, of a surrounding area. There’s a reason they haven’t invested in southern Dallas. Instead of bringing in stores that would need to be subsidized to stay in business, we should focus on stimulating organic growth. And as for Mockingbird Station, be careful what you wish for.

Instead, to guide development in southern Dallas, I propose we look to the Bishop Arts District, a 10-block neighborhood in Oak Cliff. Its evolution over the last 30 years has a lot to teach us about what makes a successful neighborhood and where investment is best made. Applying what we’ve learned in Bishop Arts to small redevelopments in the city’s south would bring amenities and job opportunities closer to where people live so they don’t have to spend half a paycheck to own a car and drive to Far North Dallas.

Let’s start with the history. Like much of early Dallas expansion, the original Bishop Arts grew up around a streetcar stop. By 1940, the population density of the census tract was more than 12,500 per square mile, enough to support transit ridership and a neighborhood center. In 1960, 23.5 percent of residents rode the streetcar to work and 8 percent walked, presumably to jobs nearby. This was a complete neighborhood.

The significant shift in area fortunes occurred in the 1970s, when school busing was imposed upon this very segregated city, contributing to white flight. But the diversification of a neighborhood—going from 96 percent white in 1970 to 48 percent by 1980—was not the problem. Rather, it was the loss of the middle class of all races. In 1970, the census tract surrounding Bishop Arts had a median household income of $55,000 (in 2018 dollars). By 1990, median household income had dropped to $32,000. Forty percent of the population lived in poverty, the threshold at which experts say it is nearly impossible to achieve upward mobility. When the middle class leaves, they take their demand for services with them, pulling up the ladder of opportunity as well.

During this downward spiral, Jim Lake began to buy some of the historic buildings. His first step was to get a police substation placed in one of the buildings, providing some measure of safety and security. In the early 2000s, the city invested by rebuilding the streetscapes with trees and brick sidewalks.

Then—and perhaps most important—the zoning for restaurants and retail parking was cut in half, to two spaces per 1,000 square feet, and allowed to be consolidated in one spot. That meant that opening a new business didn’t require tearing down an old building to provide parking. Lastly, the surrounding area was rezoned to allow greater density, thereby creating a bigger local customer base.

From 1999 to today, the area has increased permanent jobs from 237 to more than 900, which doesn’t include the construction jobs created by the redevelopment. The assessed taxable value of just the small cluster of historic, mostly one-story commercial buildings has grown from a total of $2 million to well over $11 million. Meanwhile, the property tax revenue increased from $14,750 to $122,821 per acre, more than recouping the city’s investment in place-making.

To replicate the success of Bishop Arts (note: not replicate Bishop Arts itself), we must formalize the parameters, processes, and investment streams that made it work. My proposal calls for doing many of these redevelopments simultaneously and compressing the time frame.

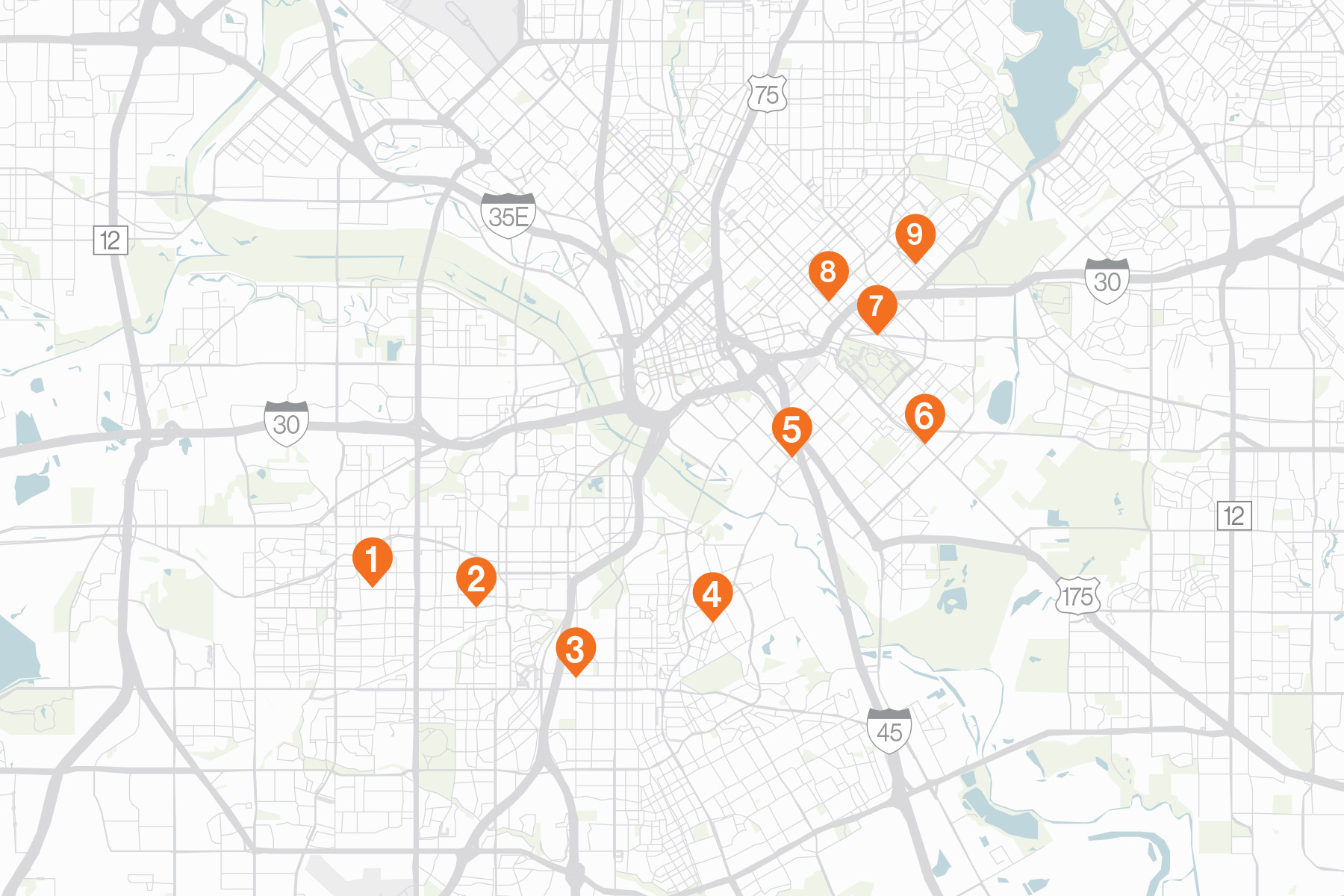

The first step is to identify which neighborhoods can support this kind of turnaround. To produce real value for the public effort and investment required, neighborhoods should have relatively high unemployment, low incomes, historic building fabric, and solvable infrastructure issues. I have selected eight old streetcar stops identified from a 1929 map and one near an old rail line. Many of these areas, like the prewar Bishop Arts, were once thriving centers of activity, integral parts of the surrounding neighborhoods. The target areas should also have stable working- or middle-class neighborhoods nearby so that the land between them attracts investment during the transition.

The second step is to reverse 1970s decisions that widened roads to increase vehicular throughput. By giving priority to cut-through traffic, the new infrastructure discouraged businesses and the residents who might want to walk to them. To repair these mistakes would cost about $1 million to $2 million each, roughly what was spent on Bishop Arts and Lower Greenville, respectively, to calm traffic and improve pedestrian safety and comfort. Redesigning and rebuilding nine places would require only about $15 million over a rolling 20-year span.

The next step would be to relocate public services into some of the historic buildings, just like we did with the police substation in Bishop Arts. Maybe a small-business resource center could partner with local architecture, engineering, and business schools. The design resource centers should work with the local community to develop and administer an area plan and rezoning.

Imagine a city of city builders.

The new plan and rezoning must include a few critical components: eliminate onerous minimum parking standards; be form-based rather than land use-based to allow for mixing of uses that complete places require; build adjacent “missing middle” housing prototypes such as townhomes, duplexes, and four-plexes to provide a greater range of housing types and affordability; offer an expedited permitting and review process for working with the Design Assistance Center and utilizing preapproved development prototypes; and “de-pollute” the land by erasing old liens, locating lost deeds, and, if an economic development agency or redevelopment authority is involved, helping with site acquisitions.

The areas in question are far too risky for investment from large institutions. Instead, we mitigate risk by making small-scale investments and then further mitigate that risk by “swarming” the area and building momentum with many hands working on many small developments clustered in the same area. We have a shortage of small developers. The city could partner with The Real Estate Council to establish a developer training certificate program and a revolving “conscientious capital” fund for zero-interest capital. We are also experiencing a shortage in the construction industry. As part of this effort, a construction trade and mentorship program should be established, with the goal of fostering human capital within the construction industry, so that day laborers can work their way up to being skilled tradesmen, to contractors and general contractors, and eventually to developers or investors themselves.

Lastly, the surrounding neighborhoods need to awaken to the possibilities. Establish regular pop-up markets for local entrepreneurs as part of a block party in the street. People need to see public streets differently, as public places for people and activity, not just cars. When that shift occurs, little businesses can start to take advantage of the renovated location: the lady who does sewing out of her home, the family who sells tamales to their neighbors. Then a few more and a few more as the city invests in the streetscape to improve the pedestrian experience and make the block party feel more like a daily occurrence. At this point, the market begins to shift, the swarm can occur, and sites can be readied for larger-scale investments.

Nine Little Centers Ripe for Renovation

These neighborhoods are primed for redevelopment. Most were prewar streetcar stops. They are within census tracts of less than $50,000 median household income, with stable working- and middle-class neighborhoods nearby (with the exception of Second and Carpenter, in South Dallas, which will be the most difficult to rebuild). Named by nearest intersection:

1: Pierce and Catherine

This intersection is nestled in a stable working-class neighborhood where the median household income is the same as citywide, $45,000 per year. Little imagination is necessary to bring these derelict commercial structures built in 1939 and 1952 back to life. Some pedestrian-friendly streetscaping and some business concepts are all it needs.

This intersection is nestled in a stable working-class neighborhood where the median household income is the same as citywide, $45,000 per year. Little imagination is necessary to bring these derelict commercial structures built in 1939 and 1952 back to life. Some pedestrian-friendly streetscaping and some business concepts are all it needs.2: Edgefield and Clarendon

Built in 1923, the building on the northwest corner of this intersection is one of the most attractive in the city. The intersection is at the nexus of two census tracts with median household incomes of $43,000 and $54,000. With Winnetka Elementary across the street, provided some TLC, this area could function as the center of the surrounding community.

Built in 1923, the building on the northwest corner of this intersection is one of the most attractive in the city. The intersection is at the nexus of two census tracts with median household incomes of $43,000 and $54,000. With Winnetka Elementary across the street, provided some TLC, this area could function as the center of the surrounding community.3: Woodin and Beckley

Businesses already occupy a 1926 building, but with vacant parcels across the street on both sides of this T-intersection, there is no sense of place. Some incremental infill development, along with improved pedestrian connections to and from the surrounding neighborhood, will bring this neighborhood center to life.

Businesses already occupy a 1926 building, but with vacant parcels across the street on both sides of this T-intersection, there is no sense of place. Some incremental infill development, along with improved pedestrian connections to and from the surrounding neighborhood, will bring this neighborhood center to life.4: Cedar Crest and Bonnie View

Cedar Crest Boulevard is built to carry more than 30,000 cars per day but barely carries 5,000 per day. The intersections are hostile to pedestrians. Though there are only about 5,000 residents within walking distance, this village cluster could be the place to go after a round at Cedar Crest Golf Course, less than a mile away.

Cedar Crest Boulevard is built to carry more than 30,000 cars per day but barely carries 5,000 per day. The intersections are hostile to pedestrians. Though there are only about 5,000 residents within walking distance, this village cluster could be the place to go after a round at Cedar Crest Golf Course, less than a mile away.5: Martin Luther King Jr. and Ervay

Less than 1 mile from The Cedars, this intersection has the best built fabric in the area. Cosmetic streetscape efforts along MLK haven’t helped. The streets require functional transformation to calm traffic and provide safety for pedestrians and bicyclists alike. Narrow the rights of way and recapture public land for infill and redevelopment.

Less than 1 mile from The Cedars, this intersection has the best built fabric in the area. Cosmetic streetscape efforts along MLK haven’t helped. The streets require functional transformation to calm traffic and provide safety for pedestrians and bicyclists alike. Narrow the rights of way and recapture public land for infill and redevelopment.6: Second and Carpenter

We shouldn’t fear investing in downtrodden areas. Pedestrian safety and amenities are not the sole domain of the wealthy. In fact, it’s the most cost-effective way to build in terms of public return on investment. But that would require smart place-based infrastructure investments, the opposite of what we have done in South Dallas for the last 40 years.

We shouldn’t fear investing in downtrodden areas. Pedestrian safety and amenities are not the sole domain of the wealthy. In fact, it’s the most cost-effective way to build in terms of public return on investment. But that would require smart place-based infrastructure investments, the opposite of what we have done in South Dallas for the last 40 years.7: Haskell and Grand

Intersections are the basic atomic element of cities. They are the convergence points where “third places” thrive. That is, unless the intersections are not designed for human activity but instead to facilitate car movement. A revitalized Fair Park and some redesigned street networks could reposition this area to be the next Bishop Arts District.

Intersections are the basic atomic element of cities. They are the convergence points where “third places” thrive. That is, unless the intersections are not designed for human activity but instead to facilitate car movement. A revitalized Fair Park and some redesigned street networks could reposition this area to be the next Bishop Arts District.8: Peak and Main

This intersection is really a radius of several blocks, a hodgepodge of surface parking, vacancy, and clusters of architectural gems. A DART bus maintenance facility sits right in the middle of this potentially great area. Perhaps we work to move public facilities to less valuable land and leverage the existing land for mixed-income, housing-led revitalization.

This intersection is really a radius of several blocks, a hodgepodge of surface parking, vacancy, and clusters of architectural gems. A DART bus maintenance facility sits right in the middle of this potentially great area. Perhaps we work to move public facilities to less valuable land and leverage the existing land for mixed-income, housing-led revitalization.9: Lindsley and Beacon

Head to this link to buy a copy of the issue and learn more about our July 11 urbanism symposium at the Dallas Museum of Art.