The construction of Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport was something like a shotgun wedding. Most Dallas residents were perfectly happy to keep flying planes in and out of Love Field. Fort Worth had Meacham Field and would have preferred that the growing amount of air traffic coming to North Texas in the late 1960s kept coming there. But federal regulators had other ideas. They weren’t going to continue to support the operations of two regional airports.

Dallas and Fort Worth have been, for most of their histories, like cousins from opposite sides of the tracks. Each has thought of the other as living on the wrong side. “They didn’t want to talk to each other. They didn’t want to have anything to do with each other. Because they were still small, because they were separated, they didn’t really see a need to do it,” says Mike Eastland, executive director of the North Central Texas Council of Governments, an organization created by the state in 1966 to allow—or force—the region’s cities to work more effectively with each other.

Begrudgingly, the two biggest cities in North Texas collaborated on building DFW Airport, which opened in 1974. Now an entire generation of American travelers has come to know our region as “DFW” and to think of Dallas and Fort Worth as twin cities. Which is not to say that leaders in “D” and “FW” feel the same. Even after the airport’s remarkable success in bringing corporate relocations and economic growth to North Texas, the cities clung fiercely to their independence and sought competitive edges for themselves.Even cities in the far-flung reaches of Denton and Collin counties want in on the fun and have joined to support the efforts.

Then development came to the “mid-cities”—development largely spurred by the new airport. Empty spaces along interstates 30 and 20 filled up with stores, offices, and homes. Regional problems, like pollution and transportation, grew to the point that mayors from all over North Texas found that they had to cooperate to confront them. Once-small cities like Arlington, Plano, and Irving came into their own—and added even more competition (most especially for economic development) to the mix.

So when the organizers behind the effort to bring Super Bowl XLV to Cowboys Stadium in Arlington decided that they needed a coordinated effort from dozens of local cities and counties to pull off their plans, they were by no means facing an easy task.

“Dallas, Fort Worth, Arlington, and the mid-cities have never worked very well together, generally speaking,” says Mayor Robert Cluck of Arlington. “I guess they’re all kind of interested in their own city.”

By selling local leaders on the idea that the region could see an economic impact of more than $500 million from the big game and its many satellite events, the North Texas Super Bowl XLV Host Committee managed to marshal support from each of the four major counties affected by the game, 12 convention and visitors bureaus, and more than 100 area cities. While each of them sees a benefit to bringing national and international exposure to North Texas, they’re all still hoping to get something out of it for themselves as well.

Spreading the Wealth

“It’s like anything else: Everyone’s got personal agendas,” says host committee chairman Roger Staubach. “[I’m] in the real estate business, and when we represent a company, the region wants them to come, but then all of a sudden—once they’re here—‘Are you going to go downtown? Are you going to Fort Worth? Or could it be another city?’ We knew everybody was in this together to win the bid, and then everybody also wants to be able to have some of their personal agendas achieved.”

North Texas organizers kept those competing self-interests in mind as they suggested sites for various events to the National Football League. Though the NFL makes the final determination on venues, it was largely at the urging of local organizers that Fort Worth, Dallas, Arlington, and Irving are all sharing in pieces of the action—not to mention the dozens of other municipalities that are likely to host unofficial parties and house and feed tourists in their hotels and restaurants.

“We want to do as much as we can with the personal agendas,” Staubach says. “We want to have this thing here again. If we don’t [pay attention to the personal agendas], we won’t have the cooperative spirit that’s needed to win it again.”

“This is the North Texas Super Bowl. And it’s not an issue of big city vs. little city,” says Fort Worth Mayor Mike Moncrief. “You don’t hear that kind of infighting and bickering around here. The city limits and the county lines are fading into one portrait, and it’s up to us to paint that portrait. It’s up to us to make sure that it contains the right blend of all of our cities in those colors.”

Dallas Mayor Tom Leppert agrees. “The Super Bowl is a good example of how the region is coming together to work on something that’s significant and that’s got a big upside,” he says. “But I think you’re also seeing the region work more closely on what you consider some of the problems that are out there.”

Cluck says it took time for the cities to learn to work together: “It’s not a normal thing for the Dallas-Fort Worth area to work together in unison. But I’d say after two months of working together, of talking about it, everybody started marching together and realizing that all of us together can do wonderful things, but each of us can’t do very well by ourselves.”

Far-flung Benefits

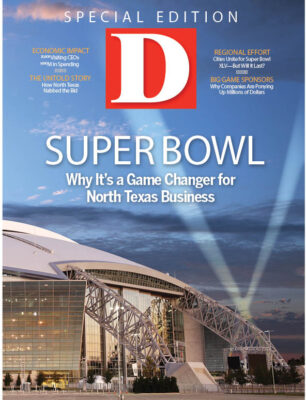

Cowboys Stadium in Arlington will host the game. The NFC championship team will stay in a hotel in Irving. The AFC champs will stay in Fort Worth. The NFL will make Dallas its headquarters for the week leading up to Feb. 6. But even cities in the far-flung reaches of Denton and Collin counties want in on the fun and have joined to support the efforts. With about 250,000 people expected to come to North Texas for Super Bowl weekend, some travelers may indeed trek to the game while over-nighting in Lewisville or McKinney.

“When you’re bringing this number of folks in and you’re exposing them to a region, and you’re exposing them to people from this region, everybody’s going to have a chance to promote themselves to a certain degree,” says the council of governments’ Eastland.

Denton Mayor Mark Burroughs expects his city—about 40 miles from the ball field—to see effects from the Super Bowl in its hotels, on its roads, and at its municipal airport. That’s why he’s stayed an active supporter of the host committee’s efforts. “We need to make sure that we … put Denton on the map for folks coming from all parts of the country, and outside the country, to have a place where they can stage,” he says.

Flower Mound Mayor Jody Smith won’t have a hotel open in time but expects special events to be booked into Circle R Ranch, which can give out-of-towners “a little idea of what Texas is like.” Parker Mayor Joe Cordina expects thousands of tourists to come to his city the week of the Super Bowl, to tour the famed Southfork Ranch of the Dallas TV series fame. The mayor of tiny Krugerville, Erich Ransleben, doesn’t have any venues or hotels in his small town to promote, but even he expects to see some payoff.

“Financially [the region will] benefit from it,” Ransleben says. “Everybody does.”

Moncrief says visitors will see Fort Worth for the “shining star” that it is, but that the same can be said for Dallas or Arlington or North Richland Hills or Saginaw, as the Super Bowl spotlight will benefit the entire region.

“Our responsibility is to take advantage of that spotlight and to do so without stepping on each other,” he says.

Talk to those who were part of the bid to bring the Super Bowl to North Texas, and they will stress that the game’s impact is so big that hosting it had to be undertaken on a regional level. And a major sporting event like this can have benefits beyond whichever city happens to be hosting, they say.

“The legacy of this game, if we do it well, will be a united region that understands we have our unique signature identities, but we are also more powerful as a unit than we are as individual cities,” says Bill Lively, president and CEO of the host committee. “We’ve never had that spirit. We do now, and it took a sports event, and a stadium where it is, to make that happen.”

Beyond the financial effects, the area’s leaders are hoping that the game will foster a new sense of unity and cooperation that makes it easier for them to work together on longer-term matters like regional transportation and environmental concerns. While no one will know for sure how that plays out until months and years after Super Bowl XLV becomes a memory, there is hope among those involved.

“You know, [Dallas Mayor] Tom Leppert and Bob Cluck and myself work daily together on issues that go beyond our city limits or our county lines,” Moncrief says. “Now we’ve got one more project to work on, and we know that it’s going to bring millions of dollars into this North Texas region.”

Cluck saw evidence of the new spirit of cooperation when he testified in Austin recently before a legislative committee along with Moncrief and Leppert.

“I was talking to Tom Leppert,” Cluck recalls. “We sat by each other, and somebody came up to him and said, ‘If you were mayor of Dallas, I guess you would have fought harder for the stadium.’ His response, which I thought was beautiful, was, ‘We’re all going to win. It’s going to be good for everybody.’ I appreciate that comment, because I think it’s true.”