Now, during a short pause as he looks at the score, one of the cellists with his finger on the music asks Van Zweden something I can barely hear. Maybe: “Do you have this note?” Van Zweden looks at him, strikes a stance, and replies, “It’s your note—I hope!” It comes across as mildly sarcastic, meant to amuse (however uneasily) the rest of the orchestra and sting the cellists a little into owning their performance. He’s testing them. (Later, when I ask Van Zweden about it, I mention that the cello players did something that he didn’t like, and he says quickly, “The cello players did something that they didn’t like.”) The moment passes, another segment follows—some matter with the principal bassoon.

“Two-eighty-four!” Van Zweden calls out, raising his hands. The orchestra plays, and almost immediately, he waves them to a stop. Now he’s talking directly to the cellists. There’s something “dangerous” going on. He has them go through the passage, but it’s still not what he wants. Later he explains to me that in an extended phrase, the cellists have to “change the bow” from one direction over the strings to the other direction. He’s hearing them stop the phrase and start it again during the change; it needs to be continuous. “What about outside-inside with the bowing?” he asks. “Old bowing,” he says, leaning to one side, clowning a little, then leaning back the other way, “new bowing.” It’s the kind of solution he could not have offered unless he had been a performer himself—a celebrated violinist—for many years before Leonard Bernstein told him he should be a conductor.

He takes them through it several more times. The cellists in back aren’t giving him enough volume, so he tells them to pick it up. Yes. “Perfect!” He immediately turns to the whole orchestra. “Two-eighty, please! Two-eighty!” Everybody plays, but he cups his ear, not stopping, toward the cellos in back. “I missed you,” he calls. And several bars later, he’s angry. He stops the orchestra. “This is an important moment!” he tells these poor cellists whose faces I can’t see. “The sound drops off”—he makes a gesture like the falling blade of a guillotine—“and you are late, always late! Be careful with that, please!” He has the whole orchestra play it again, and this time, he finally has the cellos’ attention. He stops them, looks in their direction with a slight bow. “Excellent! Thank you.”

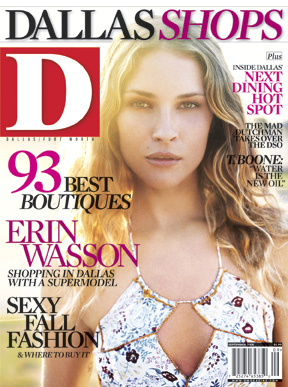

Ask the musicians, and they’re unequivocal about Van Zweden’s strengths. “He is incredibly intense, and he’s incredibly focused and very demanding,” says principal oboe Erin Hannigan. Wilfred Roberts, principal bassoon, has been with the DSO since 1965, and he says that Van Zweden is one of the most energetic conductors he’s ever played for, and that his energy goes into the music. “He’s extremely high energy,” he says, “both as a conductor and as a person.” Van Zweden is also very clear about what he wants, as principal trumpet Ryan Anthony points out. When Anthony first worked with Van Zweden, not only was the physical conducting transparent in terms of his intentions, but Anthony was also “extremely impressed with how clearly he was able to explain verbally what he wanted.” That’s a common thread in descriptions of him. “He’s very specific in what he wants—extremely specific,” Roberts says. “He’s going to leave no doubts about the way he wants things. The musicians of the orchestra have no doubt that he’s going to insist that they be done that way.”

The impact of this specificity was immediate back in November when Erin Hannigan first worked with him. “The orchestra played at a level that not very many conductors could bring it to,” she says. “Every now and then we’ll have a conductor and you’ll wonder whether they’re already thinking about their flight home. I feel like he’s 100 percent there, 100 percent committed to making it what it should be.”

Will dallas be able to sustain its excitement over a Dutchman who conducts classical music? If you’re a young professional musician like Hannigan, giving back a total commitment hardly seems a chore, but in what sense can Dallas be “100 percent committed” to the music Van Zweden conducts? When I say Dallas, I’m really talking about a relatively small group of people who attend the symphony, and of that number, I suspect that—well, that even many people who usually listen to WRR rather than 1310 AM or 99.5 FM tend to be ballpark recognizers of the classics (“That’s Mozart, right?”) rather than truly discerning listeners. Alone in the car, midway through a keyboard sonata by Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach or an obscure Schubert lieder, aren’t they going to push the button for All Things Considered? They weren’t born in Vienna or one of the displaced European neighborhoods in Manhattan where people grow up drinking classical music through genetically privileged ears and mastering an instrument from infancy. Jaap van Zweden, as Wilfred Roberts stresses, is “out of the European mold—he’s a truly European conductor.” What exactly that means would take too long to explain, he says, but I suspect it has to do with more than the repertory he mentions. Europeans seem different—an admittedly breathtaking generalization—and when I interviewed Jaap van Zweden, I wanted him to tell me why. Here in Texas, we don’t naturally reach for violins and cellos—even if some Highland Park supermom clasps her laden womb with a Bose headset and plays Eine kleine Nachtmusik through the amniotic tides. We’re not dumb; we can catch up. Still, the prospect of really learning to listen with a more than general pleasure can be daunting.

In his latest book, Musicophilia, neurologist Oliver Sacks tells the story of a surgeon struck by lightning as he was talking on a pay phone. A bolt of electricity burst out of the receiver and knocked him backward; he went into cardiac arrest and had an out-of-body experience. Weeks later, after he had fully recovered, the man developed “this insatiable desire to listen to piano music,” though his preferences before had been primarily rock ’n’ roll. Not only did he devour Vladimir Ashkenazy’s recordings of Chopin, but he began to learn to play the piano himself. He kept up his surgical practice uninterrupted, but in his off hours read books on musical notation, hired a teacher, worked at it alone, with no friends who shared his passion, and then began trying to capture some of the music—his own—that was constantly running in his head. Sacks reports that at a concert many years after he was struck by lightning, the surgeon played two pieces on his new Bösendorfer grand piano, one from Chopin, one his own composition. A concert pianist who heard him said that he played with “great passion, great brio.” He wasn’t just a clumsy enthusiast, either; he played, “if not with supernatural genius, at least with creditable skill, an astounding feat for someone with virtually no musical background who had taught himself to play piano at 42.”

It’s a story like the conversion of St. Paul on the road to Damascus. It moves us. Maybe something like that could happen to us, we imagine, or maybe it already had in Jaap van Zweden’s concerts in November. Patrons might not have been able to surmount the innate difficulty of translating musical experience into language—for example, they couldn’t have said what made Beethoven’s Symphony No. 6 hang together so well in the performance—but they had felt a new force and presence. The music had done something to them, and not at all something rote. Down there in front, that commanding man had been struck by lightning, and he had released a spirit neither of warring angels nor of totemic animal powers into the orchestra, but invoking each and restrained from either into a splendor of the human.

“I was 7 years old,” he says. “My father was a pianist.” He’s speaking very quietly, remembering his father, still a concert pianist at 81. “He started to—just to make music with me when I was a young kid, just 7 years old. I immediately asked for the violin, and he rented an instrument for me.”

It’s early afternoon on April 24, a few hours before Van Zweden will conduct the combined orchestra and chorus in Verdi’s Requiem, and he sits behind a desk in his office in the Meyerson, holding an old score of Verdi that he places near him on the desktop. He is very attentive, entirely present, his English excellent—except for his pronunciation of the word “enthusiastic,” which I do not understand the first time. Just before asking him how he first discovered his talent, I wanted to know how the Dallas audience compared to European ones in terms of their preparation to listen with discernment, and he said that Dallas audiences were “extremely enthusiastic.” Yes, I had thought, but what will happen when they give a standing ovation to a performance you know was flawed?

“You were never tempted to play any other instrument?” I ask him.

“Strangely enough, no. No.”

“Can you say why?”

“Well,” he says after a pause, “when I put this fiddle under my chin, it felt like, ‘I am complete now.’ And before, you know, I was extremely—I was an extremely happy kid, but there was always something missing in my life until I was 7. And then, my father gave me this instrument, and I started to learn some. I immediately felt that this was right. And then, I heard some records, and then I completely fell in love with music.”

“I heard you the other day in rehearsal,” I say, wondering what would have completed me at 7. “You would sort of sing a part of it, and then I would hear the orchestra do it.”

He smiles. “When you play music, you should always sing it. It’s very important. The moment you are playing notes,” he says authoritatively, “is a dangerous moment, because if you play notes without singing inside, then the music stops.”

That’s what he meant when he was talking to the cellists and the word “dangerous” floated up to me in my box. Without danger, the performer isn’t fully present to that very moment, and music is all about being in time now. Unless there’s something going on inside the musician now, then what comes out of the instrument might be sound, but it won’t sing. If there’s something Homeric about Van Zweden when he conducts, it’s that he embodies the prowling, panther-like danger of the moment of playing notes. He requires the most intense alertness, and his specific expectations, note by note, make the danger felt in every particular. “You have to become one with the music,” Van Zweden explains to me, his voice low again.

He sings inside as he’s conducting, sometimes letting it out as he did during the rehearsal, restraining the orchestra, holding them back at the end of the “Kyrie,” until with the next note they plunge headlong into the tumultuous “Dies Irae.” Van Zweden stops the orchestra to tell them, “On the first note no accent—is that right? ‘Accent?’ ” he asks, not trusting his English. They laugh and start over. The music climbs. Four huge beats on the drum—wild, swirling music, the upward screams of the piccolo. Trumpets, trombones—then low and ominous on the violins. Pure presence. Van Zweden puts one foot forward, leaning into the orchestra, and the trumpets high up above start growing through the “Tuba, mirum” section, gaining in volume. Soon, it’s high and wild, and halfway through, he puts a halt on it, leaning back against its momentum like Superman stopping a runaway train. He calls out a number, and the music slows, his shoulders go up and down through the notes—just his shoulders—and he lifts both hands, an overhand rolling gesture to call forth something, and the drums are huge, huge.

“When you sing inside, that is the moment when everything falls in its place,” he says. When he gets a completely new score, such as Steven Stucky’s August 4, 1964, which he conducts in its world premiere this month, he says that he tries “to sing inside a little bit if there is singing in it. I don’t do it aloud, because my singing is very bad.” He smiles again. “But inside I try to sing a little bit and see how it sounds on the piano. Then, you start to do your technical things. For example, from where is the phrase starting and where does it stop? And then you just hope that it will sound like you hear from the inside. First, you have an inside voice that is singing, and then you start to hear this new piece, and you hope that it will also click with the musicians.”

What first attracted Van Zweden to Dallas was the reputation of the DSO—a point that might seem a little counterintuitive at first. “I mean the orchestra has a fantastic name in the orchestra world. And I know that the orchestra had major, major music directors. Dorati!” he says excitedly. “You should know that I worked with Dorati for many years. I worked with him every year. I was at his house in Switzerland, where I still have contact with his wife. She just greeted me at a concert in Lucerne. I mean, there is a relationship there, and she was so extremely happy that I went to Dallas. She says, ‘Oh, yeah. Antal was there and we had such a fantastic time.’ So that was quite interesting. Solti, not to forget. Eduardo Mata.”

Georg Solti and Eduardo Mata, sure. But Dorati? I’m ashamed to say that I have to look up the name on the DSO’s website, but there it is: “Antal Dorati transformed the ensemble into a fully professional, first-rate orchestra that won national attention through a series of RCA recordings, expanded repertoire, more concerts and several national network radio broadcasts.” In other words, he virtually created the modern DSO—from 1945 to 1948. He left Dallas 60 years ago, and he died 20 years ago, in 1988, when Jaap van Zweden was still a violinist. He still feels a warm, living bond with the man and feels his presence here in the orchestra itself, from an era long before many of these musicians were alive, and long before the Meyerson itself was even conceived. Maybe it’s part of the musician’s habit—finding the living soul in the works of a composer dead for centuries and singing him back to life.

He loves the Dallas Symphony Orchestra, then. He felt an instant bond. “I got the feeling that they understand how I read music inside,” Van Zweden says. “They talk the same musical language as I do. You don’t have that with every orchestra. It’s a blessing, actually. If you meet each other on the podium for the first time and you have the feeling like, ‘Wow, I’m coming home, and this is completely new,’ then, after the first rehearsal, you go to your hotel, and you are extremely happy—” He compares what he experienced with the DSO to telling a story to someone and having the other person respond with immediate recognition. “The other person says, ‘Yes, that’s exactly how I feel about it. That’s exactly how I think, and this is how I feel.’ You think, ‘Wow, that’s incredible.’ That was how it was with this orchestra from day one.”

Still, getting the music to click takes diplomacy, both for the conductor and for the musicians. “You have to respect the overall soul of the orchestra and how they used to do time, and if I can get them with me so they can understand what kind of timing I want—I listen very carefully to what they want, and then we have to get together in that process of rehearsing.”

That’s what was going on, I realize, in Van Zweden’s exchange with the veteran Wilfred Roberts in his bassoon part—technically not a solo but an obbligato—during the April 22 rehearsal of the Requiem. I remember the moment well: putting the rest of the orchestra on hold, Van Zweden spoke to Roberts, who looked—from where I sat—taken aback if not shocked. “Okay,” Roberts said to Van Zweden. “Okay,” he said, nodding.

When I ask Roberts two months later about that moment, he remembers it more distinctly than I do. “There’s a group of six notes that returns for several minutes, over and over and over, and he wanted the first note of each group more emphasized and more separated from the others, slightly more accented than is the norm.” Roberts says. “I’m used to playing that first note as a little more genteel, and he wanted it more emphasized and separated. It was what he wanted and I just changed and did it.” There’s a slight undertone in his voice—not much, just enough to let me know that it registered with him as a dangerous moment, to use Van Zweden’s word. “That particular exchange—I don’t know that I’d call it an ‘exchange,’ though I see why you’d call it that. We played through the whole thing. And then he came back, and he just asked me the one thing. When a conductor asks you to do something different, you do it. He’s the boss. I could do it either way, but that’s the way he wanted it and it worked very well.”

Did it work, in fact? The reviews of Verdi’s Requiem came in strong, and the praise for Van Zweden remained high. The “Dies Irae” section, especially with the full chorus, struck into sublime territory. Yet the performance I attended on April 25 did not leave me as exhilarated as the Beethoven concerts had back in November, largely because the four soloists between Van Zweden’s back and the audience seemed more a distraction than an addition—this despite the fact that Verdi built these major voice parts into the core of the Requiem. At least on one occasion in the concert, Van Zweden glanced sharply back at the bass soloist—not that the man could see him. Later, I read Scott Cantrell’s review of the April 24 concert for the Morning News, and he nailed the specific problems. He criticized the soprano for a voice “more creamily Straussian than spicily Verdian,” the mezzo for not quite “stirring the blood,” and the bass for uncertain intonation and “little in the way of line or elegance.” He praised Stuart Neil for producing “the biggest-beef sounds I can remember hearing from a tenor, but also exquisite hushed croons. Unfortunately, there wasn’t much in between.” It struck me as ironic, especially given all Van Zweden’s emphasis on singing, that the operatic singers kept the Requiem from having the full effect otherwise being unstintingly delivered by the orchestra and the chorus, both of whom rose to the occasion splendidly.

At the end, Van Zweden turned to the audience, but not as he had back in November after those flawless Beethoven concerts. Then, his whole demeanor showed a confident gratitude for the audience’s appreciation; this time the strangest expression played on his face. The concert had loose ends, weaknesses, yet the audience rose to its feet just as it had before, as if on cue. Enthusiasm, cheers. As he bowed during the continuing ovation, he showed a puzzled gratitude—or was it doubt? Was he being given a vote of confidence despite the flaws in the performance? Or if the praise was genuine, could it mean that the audience did not know the flaws were there? They were applauding the soloists enthusiastically. Bravo! Bravo! But were they also applauding his interpretation of Verdi—more emphatic and less “genteel” than usual—or not? Was this some phenomenon of enthusiasm owing more to expectation and buzz (UNLEASHED) than to the music? Watching him, I thought that the moment an orchestra stops playing notes also carries in it an extraordinary danger, this time for the audience, because it is being asked for judgment, not just for praise.

To my mind, a little less applause would have praised Van Zweden more. There’s an implicit question here about Dallas’ ambition to have a great orchestra. Jaap van Zweden applauds ambition—for example, what’s going on in the Arts District. “It’s incredible what this city is doing in the arts. It’s fantastic—it’s people, not just the government, who are donating and who are so connected with this city that they give.” He likes it all. He applauds the ambition of the front office of the DSO. “We have people who are visionary who go and look out for where we can play. It’s very important. We have a fantastic staff,” he says.

But the most important thing for him is not an imagined future of greater acclaim, the kind of comparative anticipation—“We’re going to be like New York!”—that can sometimes distort the experience of what is already here. This is what Van Zweden wants: “To create onstage that magic which we had in the previous concerts. That’s the biggest concern—to give great concerts. The word ambition is good, but it is also dangerous. When you have a lot of ambition, then you think ahead, and sometimes you can forget what is going on at this moment.”

He straightens in his chair and says definitively, “There is—you know, there is only now in life. There is not yesterday, there is only NOW. THIS is the moment.”

It’s all about timing.