One day in February 2006, Fred Bronstein settled into a box seat at the Meyerson Symphony Center to check in on the orchestra’s second rehearsal with visiting conductor Jaap van Zweden. Bronstein had seen Van Zweden conduct before, in London, but this was the first time the DSO’s president and CEO had seen the Dutchman work with the Dallas orchestra. As he often did when he sat in on rehearsals, Bronstein started multitasking—reading papers he’d brought from the office, checking his BlackBerry.

Twenty seconds into a Johan Wagenaar overture, Bronstein’s head shot up. What was that? The sound—particularly the depth and richness Van Zweden was coaxing from the string section—was unlike anything Bronstein had ever heard from the Dallas orchestra. He was stunned.

Audiences heard it, too. Van Zweden was named the DSO’s music director a year later and returned to Dallas in November 2007 to conduct Beethoven’s Fifth and Sixth symphonies one weekend, the Seventh and Eighth the next. At the end of each performance, audiences instantly leapt to their feet in clamorous applause. Never had they heard the DSO sound like this. Never before had classical music, even Beethoven’s, so electrified them. They poured out into the atrium of the Meyerson, abuzz, alight. They seemed surprised to find their clothing intact, their ears unburned, their hair not even mussed, much less on end, as it had felt for much of the concert. Such were the tender mercies of that musical revelation.

It’s not as though the DSO had been bad before. As recently as 2005, the DSO—under the baton of previous music director Andrew Litton—won a coveted Gramophone award for its Hyperion recording of Rachmaninov’s piano concertos with pianist Stephen Hough. But Dallas Morning News music critic Scott Cantrell voiced what neither Bronstein (who left this year to run St. Louis’ orchestra) nor the DSO’s musicians said publicly: “Mr. van Zweden seems ideally suited to tighten up an ensemble that coasted too often during Mr. Litton’s 12 years.” Somehow this Dutchman with a name that requires a parenthetical phonetic key (Yahp vahn ZWEH-dn) instantly wowed the city. Something had happened—something had befallen those audiences that made everything about Dallas feel cleaner and more spacious. Strangely, almost unbelievably, classical music had done this. Specifically, Jaap van Zweden had done it.

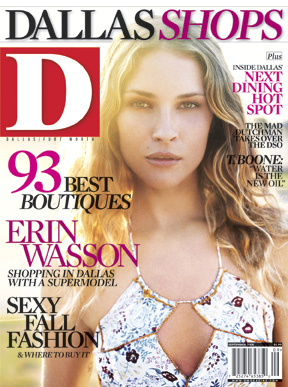

In February, handsome brochures arrived in the mail announcing his first season with the DSO, which begins this month—Van Zweden photographed in mid-concert, looking sternly to his right, both summoning and restraining the unheard music, two engorged veins on the left side of his shaved head meeting in a “V,” an apex of barely contained blood that points directly toward the baton in his raised right hand. “UNLEASHED,” said the cover. The tagline referred to Van Zweden—but it describes the orchestra, too.

How did he do it? How could an orchestra with the same 90 or so musicians, all playing the same instruments they had played for years, undergo an instant and striking change just because a different man happened to be standing in front of them?

Jaap Van Zweden is having trouble with the cellos. It’s April 22, mid-afternoon, the first rehearsal for three performances of Verdi’s Requiem, starting just two nights later. I’m in a third-level box on the right side of the Meyerson, and I can see most of the orchestra, except for the bass players on the far right and the last row or two of cellists. They’re going through the music by themselves before rehearsing with the Dallas Symphony Chorus and the four featured soloists. Van Zweden stands in front of the musicians wearing a black shirt that looks like a Nehru jacket. He’s short, thick-shouldered, with a shaved head, intense eyes, a goatee. His posture, a little stooped, must have been the despair of his mother, but when he lifts the baton, something about his bearing suggests Homeric similes: a panther that crouches and gathers itself, intent on the cattle or sheep grazing in the pastures.