The last time I went to a Mavericks game? My son was in Cub Scouts, and now he’s in college. January’s a thin month in local theater, so why not cover the biggest indoor show in town? My editors go for it, and on the night of November 5, 2007 (remember, we have a two-month lead time), when the Dallas Mavericks play the Houston Rockets in their second home game of the season, I’m here, not for the game per se, but in my capacity (cough) as theater critic. Tip-off is at 7:40 pm, but at 5:30, already in position beside the scorer’s table, Steve Letson, a thin, serious, middle-aged man, neatly dressed in a white shirt and yellow tie, sits waiting in the empty American Airlines Center. In terms of what’s called “game presentation”—the whole combo meal that the crowd gets, in which the game itself is just the patty—Letson is the man for the Mavericks, a fusion (in theatrical terms) of director and stage manager. Officially, he’s vice president of Operations and Arena Development.

“This is a game log,” he says, flipping through six or seven pages of rows and columns. “It’s just like a movie script, whatever. We usually meet, probably 10 or 12 of us who are on the game ops committee, a week before the game.” It takes that long, he explains, to work out all the planning. That’s for every single home game.

A squawk interrupts him from the walkie-talkie perched on the table to his left, and he listens, hand in midair to pause the thought: The ball kids are up on the plaza level, and we should be opening up the doors any second. “So we’ve got the doors opening,” he says. SQUAWK: We’re open, north side. SQUAWK, female voice this time: Also on the south side.

“Once the doors open,” Letson resumes, “we’ll put some music on, and then run some video on the scoreboard.” Right on cue, music begins thumping in the background. “But it’s downtime. There usually aren’t that many people getting here that early. Later, we segue into our scoreboard messages. These are just sold spots with different corporate sponsors.”

He goes through what will happen up until 7:33, when the players warming up are buzzed off the floor, followed by the national anthem, PA announcer Humble Billy Hayes’ introduction of the Houston players, the big TXU light show, Humble’s introduction of the Mavs, and so on. He goes through what’s scheduled for each planned time-out—two each in the first and third periods, three each in the second and fourth. That’s 10 different things to plan, each one sold to a sponsor. The kid who takes out the ball for the opening toss? “It’s money,” Letson says matter-of-factly.

Every second counts for something. The game itself, I start to realize, takes place entirely inside the matrix of streaming commercial flow orchestrated with the help of people throughout the building, including a crucial cadre hidden away far from sunlight or basketball. So after half an hour, Letson passes me off to Anita Green, the broadcast manager for the Mavericks, a genial woman who takes me to see the technological marvels of the video room. Fifteen or so people work all the displays out in the arena. I meet them, shake their hands, watch them do things to keyboards that I understand vaguely. They use words like “thunder” and “drop” and “Elvis” in technical ways. I smile, nod, take one of Carla’s good brownies.

What Green tells me on the way, though, is what arrests me. “We try to make it fun,” she says, guiding me through a tunnel into the caverns beneath the stands. “Because when you come to a game, usually what happens, especially when you bring a family, you’ve got the dad who’s really into the game. He wants to know what’s going on—what kind of shoes they’re wearing, who’s running what play, who’s starting. You’ve got the wife, who may be a little of a basketball fan and may not be. Then you’ve got the kids. You can’t make them sit in the chair. They want to go to the concession stand. They want to see all the pretty lights. You have to have some kind of way to keep them all involved. Or what happens is the dad wants to leave because he’s like, ‘Hey, the kids are going crazy, my wife is upset, we’ve gotta go home.’ So later he says, ‘How much fun did we have?’ Maybe the next time Dad will go with a couple of guy friends or whatever, but you don’t have that ‘We grew up as Mavs fans.’ So we try to provide the whole entertainment gamut.”

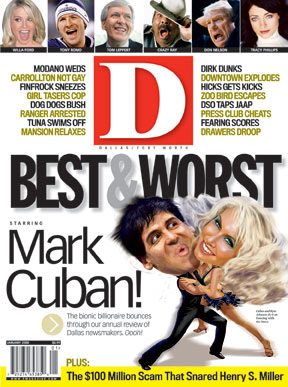

In other words—and who is this ultimately coming from if not Mark Cuban?—game presentation is about fun, but fun is about money. It has to be fun for the kids, because they are the fan base that will ensure the flow of money long into the future. It is astonishing, when you compare this show, say, to a production at Dallas Summer Musicals (recently underwritten by Comerica), how much more straightforwardly and unapologetically the whole logic of it centers on commerce.

By 7:05 pm, I’m at my seat in the press section, three rows from the court. There’s a constant din of drumbeats that I tune out, but it’s back there in my psyche. On the huge, suspended, hexagonal idol overhead—don’t tell me that thing’s a scoreboard—ads come in 10- or 30-second increments. With the script, I can check each element off, one after another, page after page. The commercials, most of them the same ones you see on television at home, make the arena familiar, family-like. Dr Pepper. Chili’s. Bud Light. You’re at the game, but the players and the experience aren’t quite real until you can look up and see it all happening on the screen, a mere shadow until it’s pixilated, just like at home. A friend of mine at the same game tells me later, “It’s like watching television, except you’re 2 feet away from the screen, and the volume’s all the way up.” Even the reporters a few feet from the court sometimes watch the television (duplicated on small screens throughout the press section) instead of the game itself—and not just for replays. Cuban, I suspect, understands these things better than Marshall McLuhan ever did. Not theoretically, but in the sense that he is attuned to the nature of money and the kinds of images that make it flow.

As the game gets underway, I’m trying to look at it as theater, this huge spectacle. The place is packed, 20,389 intermittently rowdy fans. It’s a good game, but I’m not here to watch Houston’s Tracy McGrady hit a three-pointer or the Mavs’ DeSagana Diop block a shot. I’m here to see Mavs Man approach three people, planted for this purpose, with his “mind-reading jukebox.” I’m here to see Chris Arnold get four girls to “Name That Tune” by being the first to raise their Bud paddles. (If only the Dallas Theater Center would do this at intermission!) I’m here to assess the Mavs Dancers: smiling but joyless. Too frenzied. Barbies on meth. And what accounts for the terry cloth bras with “41” on the business side and “Nowitzki” in gold letters across the strap in back? What does this do to Dirk’s psyche to be responsible for all that containment? And does Humble Billy Hayes have to say deeeeee-fense! (speaking of containment) in that creepy Munsters way every time the Rockets come down the court?

A few days later, when I’m talking to that friend who went to the game, he can’t get over the overwhelming, loud vulgarity of it. The glut of stimuli. The last thing he says, unprompted, is, “I’d never take my kids.” Interesting.

But isn’t it fun seeing the free t-shirts arc up into the cheap seats? I should watch the 360-degree LCD screen, but my capacity to be distracted weakens, and I end up watching the game. It’s the only part with a plot, and the rest is mere spectacle.

Early in the third period, Dirk gets in foul trouble, but the Mavs keep it close, and as Jason Terry walks toward Avery Johnson during a time-out, he gestures to the crowd, trying to get more excitement stirred up. What, you mean you want us to watch the game? I’m losing my sense of purpose.

In the last six minutes, the Mavs finally break open the Houston defense as Terry catches fire and scores 16 of the team’s last 37 points in a 107–98 win. The fans stream away, music throbbing, and, since the Mavs won, collect Taco Bell coupons at all the exits.

A vision comes to me: Mark Cuban as the Master of Ceremonies in Cabaret, singing to the hanging idol, “Money makes the world go around,” surrounded by Mavs Dancers going “Money money money money money money.”

As I pass him, Steve Letson, a nice guy—still there—gives me a wave.

This month, the Mavs play host to Golden State, Miami, Detroit, Seattle, LA Lakers, and Denver. Check www.mavs.com for tickets. Or call 214-747-6287. Glenn Arbery is a senior editor for People Newspapers and the theater critic for D Magazine. Write to [email protected].