THE EXHIBIT WAS CALLED SPORTS IN ART, SPON-sored by Sports illustrated, The United States Information Agency, and Neiman Marcus to benefit America’s 1956 Olympic team going to Australia. The Dallas Museum of Fine Art had agreed to host the show. One day not long before the opening, Stanley Marcus, chairman of the museum board, got a call from Fred Florence, president of Republic National Bank. Florence was worried.

“You better get over here,” Florence told Marcus. “I hear you’ve got a lot of communist art coming to the museum. The museum’s going to have a lot of trouble.”

Marcus quickly made his way to Florence’s office. Florence had heard from Colonel Alvin Owsley, past president of the American Legion, former ambassador to Ireland, and inveterate Red-chaser. He and his cohorts were raising a stink about leftist artists and “Reds” contaminating the minds of unsuspecting Americans. Angry over the political leanings of some of the artists, Owsley charged that the exhibit was full of “communist art” and threatened dire consequences if it wasn’t scuttled.

“What is communist art?” asked Marcus. Florence pointed to No. 13 in theexhibit catalog:”TheNational Pastime,” by Ben Shahn, a picture of a man hitting a baseball.

“1 don’t know how anybody could think hitting a baseball was communist,” Marcus said.

Florence pointed to another work, a painting called “Fisherman” by William Zorach. Marcus shook his head. “Well, I don’t think too many people think fishing is communist either,” Marcus said. They went through a long list of art appearing in the exhibit. None of it, as far as Marcus was concerned, was “Red art,” though a few of the artists might indeed be communists.

“Well, you better cancel the show,” Florence told Marcus.

“I can’t cancel it,” Marcus said.

Florence then suggested that he take out the paintings by the most controversial artists. But Marcus refused.

“They’re threatening to boycott your store,” Florence told him.

The specter of pickets outside Neiman Marcus, the downtown department store he and his family had built into a national legend, was not appealing to Marcus. Maybe people would cancel their charge accounts. That could cost the store a lot of money. But he refused to be intimidated. “You can tell them I said go to hell,” Marcus told Florence.

Wirh his innate understanding of public relations, Marcus realized that whoever got to the newspapers first would seize the day. If the newspapers were on his side, then the ruling elite of Dallas would he, too. He paid a visit to Ted Dealey, president of The Dallas Morning News, a paper that in those days was known to engage in a hit of Red-hatting of its own. As Marcus recalls the meeting, Dealey was characteristically blunt.

“Ted, you believe in freedom of expression, don’t you.’” Marcus asked.

“You’re goddamn right 1 do,”. Dealey told him.

“You believe in it not only for newspapers, but for artists and others, don’t you?” Marcus asked.

“You’re goddamn right I do,” Dealey said.

“And if someone tried to persuade you to censor artists’ freedom of expression, you wouldn’t go along,” Marcus said.

“You’re goddamn right I wouldn’t,” Dealey said.

Marcus then went to Dallas Times Herald editor Tom Gooch, to tell him about the Owsley boycott threat. “Tell the old fart to come around me and we’ll blow his torpedoes,” Gooch told Marcus.

“Owsley did go to the papers, but I had already shut that door,” Marcus says with a bit of satisfaction, remembering the quiet victory more than 40 years ago. The exhibit went on as planned. Civilization didn’t fall. And Neiman Marcus went on to become more prosperous and famous than ever.

It wasn’t the first and it wouldn’t be the last furor over modern art in Dallas, a city that in the ’50s and ’60s was shifting sharply to the right. But whether the controversy was overart, politics,or civil rights, Marcus’ voice of reason would be heard-sometimes hehind the scenes, sometimes on the front page of the newspaper

“Stanley has been very often standing alone on important issues,” says Liener Temerlin, a longtime friend. “He’s one of the few men who kept a well-lit torch to bring some light into issues-racial issues, poverty issues. To this day, he’s still enormously active in significant issues that face Dallas.”

“Any time there’s been an issue related to prejudice or bigotry, he’s been at the forefront of fighting those attitudes,” says another friend, developer Ray Nasher, owner of NorthPark Center.

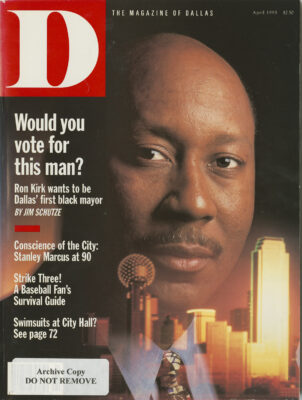

A retailer nonpareil, the man who built Neiman Marcus into a paragon of quality and Style, Stanley Marcus, who turns 90 years old this month, is known as an arbiter of taste and fashion, But less well-known, especially to Dallasites who came of age since the ’60s, is the impact Marcus had on changing the way Dallas thinks-not just about clothes and shopping, but about tolerance, culture, and living the civilized life.

Though it may be hard to believe in 1995, there were days when those ideas were considered very risky in Dallas.

HE SURVEYS THE CITY from an eighth floor office in the Crescent, looking back toward an impressive downtown skyline that has changed so drastically since he was horn on April 20,1905. Paintings and textiles adorn the walls; sculpture sits on every available surface, His taste, as always, is impeccable, his choices eclectic. The man with a “wideroving and curious” mind, as one friend describes him, has cast an eye over the 20th century and found it fascinating.

“Mr. Stanley,” as he’s called by virtually everyone, goes to work every day at the offices of The Somesuch Lecture Bureau, the consulting business where he coordinates the continuing enterprise known as Stanley Marcus. The gray suit is beautifully tailored, accessorized with an orange polka-dotted tie and a large pearl tie tack. He moves slowly but under his own steam; he professes CO keep to a daily exercise regimen of treadmill walking and weight machines. With his wife, Billie, who died in 1978, he had three children. A year after her death, he married Linda Cumber Robinson, many years his junior. Marcus recently sold the home he built in 1938 on Nonesuch Road in Lakewood to buy a smaller home in the Park Cities, the only one they could find with a suitable library for his book collection-more than 11,000 books and still growing.

Every week, he writes a column for The Dallas Morning News, Through his publishing house, The Somesuch Press, he publishes high-quality miniature books. As if that isn’t enough, he runs a consulting business for industries anxious to get his opinions about their customer service, marketing, and taste. At one time or another, it seems, he has been on every board and commission in Dallas that does anything.

The store founded in 1907 by his father, Herbert Marcus, and his aunt and uncle, Carrie and Al Neiman, was already successful when he came to work for the family in 1927, but it was Stanley Marcus’ leadership that made Neiman Marcus an international name. He’s written three books: Minding The Store (1974), Quest For The Best (1979), and His & Hers: The Fantasy World of the Neiman Marcus Catalogue ( 1982). The hooks are about retailing, hut the ideas go far beyond what sells.

When he talks about retailing, about service, Marcus’ ideas are deeply conservative, about providing value, not simply extracting the most cash possible. What pleases the customer might be a better way to describe his philosophy of retailing, or What serves the customer best, whether he realizes it or not. In today’s world of discounters and mass merchandising, his ideas seem almost quaint, tinged with nostalgia.

But there’s the other Marcus, the one who’s often labeled a liberal, or worse, a radical. What it often boiled down to was that Marcus believed in the inevitability of change, a concept that made many of his critics cringe.

“Governance, which is the hardest problem man faces,” Marcus says, “requires the ability to face changes in economic and social conditions. You have to move for-ward, or you are apt to be like the Bourbons, who never remembered anything and never forgot anything.” But he believes in evolutionary change, not revolutionary change. It’s a belief that has governed his political life in Dallas.

If evoking the powerful royal family whose rule ultimately ended on the guillotines of the French Revolution seems obscure today, the days when the ultra-right gathered strength in Dallas are not so long ago. Those were the days of Sen. Joseph McCarthy’s anticommunist crusades; of heated reaction to Brown vs. Board of Education, the Supreme Court ruling that banned segregated schools; and, of course, the Kennedy assassination.

Marcus’ approach to everything from architecture to race relations was formed early on, when he went to Harvard at age 16 in 1921. He was profoundly stirred by a course on the Greek philosopher Hera-clitus, which concentrated on the idea of change, using fire as a symbol: always changing, but in every form powerful and fascinating.

A hook he read in college also stuck with him: Folkways, by Carl Sumner, a professor at Yale University. A detailed study of cultures, Sumner’s book popularized the word mores and opened Marcus1 eyes to the way people and institutions change.

Another powerful influence was the graduation trip he took to Paris with his father in 192 5, where they stumbled onto the Exhibition Des Artes Decoratif, an early show of art deco. To Marcus it was a visual revolution-architecture that allowed new shapes and new designs, showing there was nothing sacred about the way buildings were designed. Again, that theme of change.

If there are ideas more sacred to Marcus than the inevitability of change, they’re enshrined in the Bill of Righrs, the first 10 amendments to the U.S. Constitution. And the First .Amendment, which protects free speech, is first in Marcus’ heart.

In 1995, it’s hard to imagine that the Dallas Symphony was once forced to remove from its program a piece by Shostakovich because he was Russian. That the’ Park Board had to rip out a garden planted with “Picasso Poppies” because they were red. That a rug woven by Picasso caused controversy at the DMFA. While communist scares certainly weren’t unique to Dallas, the hysteria over “Red art” seems to have been peculiar to the city. The Sports in Art exhibit, for instance, had been shown in Boston and Washington, D.C. without any suggestion that the paintings themselves were subversive or an affront to the American way.

The Marcus of the ’50s was disturbed by the city’s trend toward what he calls “absolutism,” a chauvinistic attitude toward other cultures and modes of expression not only in art, but in politics as well. The Dallas chapter of the right-wing John Birch Society was thriving, part of a vocal, vibrant minority agitating against amorphous “outside forces.” There was an arrogance, a paranoia about changes that were coming.

“They were looking not only under beds for communists, but in the bushes, under automobiles,” Marcus says. “They wanted somebody to blame.”

For a time during those years Marcus didn’t like going to dinner parties, where he was likely to run into some of the city’s most powerful, and most intolerant, people. “If you had a different opinion, your motives were constantly being sneered at,” Marcus says. Social occasions would disintegrate into vituperative discussions. “They were still fighting [Franklin] Roosevelt, though he’d been dead many years. I was a liberal in their eyes. I thought I was being a conservative, defending the Bill of Rights.”

Unlike some who shared his views, Marcus was in a unique position to make himself heard. As perhaps the city’s premier retailer, he couldn’t he ignored. But he was never one of the “yes and no” men, those key decision makers prized by Mayor R.L. Thornton. “Stanley was a lone wolf,” says historian A.C. Greene, author of Dallas, U.S.A. and Dallas: The Deciding Years. “He was not a member of the Dallas ruling group. They wouldn’t necessarily chime in when he decided he was going to do something.”

But, though a secular man, a nonpracticing Jew, Marcus carried a kind of moral authority. He was successful and rich, and Dallas has always loved that. And the Marcus name meant high quality, delivering on promises. “He stood for a great deal of individualism,” Greene says.

And there was always simple self-interest- “Even the people who were very right-wing, their wives wanted to shop at Neiman Marcus,” Greene says. Any boycott of The Store over something like art was doomed to fail when the well-to-do ladies of Dallas needed new shoes.

And Marcus knew their other weak spots, In 1952, before the Sports in Art brouhaha, Marcus had begun nudging Dallas toward an appreciation of modem art. Marcus didn’t insist that everybody like abstract art, but he wanted them to realize that there was nothing immoral or unpatriotic about doing so. He decided to put together an exhibit to make that point, inviting David Rockefeller, his brothers, and other businessmen from across the country to donate works from their collections.

Marcus received about 50 paintings, then asked the donors for another favor: He wanted them to write to their peers in Dallas-people on bank boards, heads of corporations-requesting them to go and see the exhibit to make sure the paintings were properly hung. He wanted, and got, a crowd of Dallas’ finest at the opening, mingling, commenting, and generally being appreciative of the contemporary art owned by their associates in other cities, associates who were not fringe-dwelling bohemians but big shots, bankers and lenders of large sums of capital. Marcus smiles at the memory.

“Was it peer pressure? Yes,” he says. “I can’t say it turned the tide, but it established a respectability. You may not like it [abstract art], but don’t condemn it as a communist plot.”

Eventually, the battle over art was won; in the years since Marcus gently forced Dallas to acknowledge abstract art as a cultural force, the DMFA, now the Dallas Museum of Art, has acquired a fine collection of it. Occasionally, however, Marcus still feels it necessary to take a stand on matters of art. In 1984, a charcoal drawing of two pigs mating was removed from a student art exhibition at SMU. Marcus, who owns works by Matisse, Monet, and Gia-cometti, bought it. “I always liked pigs,” Marcus told the Morning News, “but even more important is my interest in scholastic integrity and intellectual freedom, which is probably the most important thing we have in a free country.” He said he hadn’t decided where to hang the celebration of porcine amore, but was considering reproducing the image on Christmas cards.

But Marcus, while liberal, is no libertine. Every year since 1975, Mr. Stanley has given a luncheon before Christmas for a group of 30 or 40 men he calls The Good Guys. He always hands out gifts.

“The only time I’ve ever seen Stanley flustered was the year he gave us stationery,” says A.C. Greene, who is one of the group. Apparently, Marcus had ordered the stationery, but had not seen it. Called “Orgy,” the paper had notes with “’Things To Do Today” and drawings of every kind of sexual activity imaginable.

Marcus hurriedly wrote apologetic letters to all the recipients, explaining he hadn’t known about the “artwork” on the Stationery, “I wrote him back and told him I had taken him as my preceptor in the world of culture and how things should be done,” says Greene, who jokingly vowed to use the paper proudly.

Marcus was not amused.

AFTER THE BUSINESSMEN COL-lect Abstract Art exhibit, Marcus went to Willis Tate, then president of SMU.Concemed about the mounting right-wing atmosphere, Marcus wanted to bring in leaders generally regarded as conservative to give a teries of lectures under the aegis of SMU. Tate jumped at the idea. Over a period of several weeks, they brought in speakers such as Paul Hoffman, then president of Studebaker Automobile; Gerald Johnson, editor of the Baltimore Sun; and Walter Reston, president of Brown University, to speak on “ThePresent Danger”-the spirit of absolutismthat Marcus believed was permeatingDallas.

“Whether it had any effect on Dallas, I don’t know,” Marcus says. “But it provided a haven of respectability for the silent majority,” those who were afraid to speak out against the “vocal minority.”

But in the early ’60s, the situation grew uglier. The absolutist fervor was at its zenith in 1963, when a group of Republican women in Dallas spat on Lyndon and Lady Bird Johnson. A good friend of the Johnsons, Marcus was aghast. Then, in October, Marcus was with U.S. Ambassador to the U.N. Adlai Stevenson when he visited Dallas to make a speech and was subjected to the threat of physical violence at the hands of angry demonstrators.

The event in the theater of the Dallas Convention Center was intended to celebrate the United Nations. But protesters carrying placards walked outside the entrance, chanting “Get the U.S. out of the U.N.”

During the speech in the theater, Stevenson was heckled by a vicious crowd, some of them from the best families in Highland Park. Judge Sarah T. Hughes tried to maintain order, but Stevenson could barely finish his talk. Marcus, who was going to take Stevenson to dinner, recommened that they leave as quickly as possible. As the two men ran a gauntlet of hecklers to a waiting car, a female protester hit Stevenson on the head with a placard.

Marcus shoved the ambassador into the vehicle, which was quickly surrounded by shouting demonstrators who started rocking the car. “1 told the driver to gun it and we got out of there fast,” Marcus says.

Reporter Wes Wise, who would later become mayor of Dallas, was covering the event for radio and television. He shot the now-famous film of the woman hitting Stevenson, footage that helped create the “City of Hate” label that haunted Dallas for years. He remembers Marcus’ aplomb under pressure.

“Stanley Marcus did not hesitate to identify himself with a cause that he believed in-even if it wasn’t popular,” Wise says.

Not long after that, Vice President Lyndon Johnson called Marcus and told him that President John Kennedy was planning to come to Dallas. “1 thought it was unwise and told him so,” Marcus says. The right wing had gotten cocky, acting as if they were the “self-anointed rulers of the universe,” Marcus says. He was afraid the visit would be very unpleasant for the president.

“What you and I think doesn’t make a goddamn bit of difference,” LBJ told Marcus. “He wants to come to Dallas. I want you to raise some money to entertain him properly.”

Marcus set up entertainment for the afternoon of November 22 at the Dallas Trade Mart. But he had to go to New York on business that day. He was eating lunch at The Pavillion Restaurant when he got a call from his New York office. They had received a teletype: The president had been assassinated.

“We were just numb,” Marcus says. He stayed in New York that night, then went to the funeral in Washington.

When he returned to Dallas, he found a city in the midst of a great soul-searching, reeling from the accusation that the prevailing spirit of the city-not Lee Harvey Oswald-had somehow killed the president. Marcus took out a half-page ad in both newspapers asking and answering the question: “What’s Right With Dallas ?”

“It was about where the city stood and what it needed to do,” says Greene. “Once again, he was talking to the high-ticket people. It helped mark the end of right-wing affiliations that a lot of people were making, possibly without realizing what they really stood for.”

A calm, reasoned defense of the city, the ad called for a ’’rejection of the spirit of absolutism for which our city had suffered,” and the acceptance and tolerance of different points of view. “We believe our newspapers have an important contribution to make in regard to this matter and we hope they will lead the way by the presentation of balanced points of view on controversial issues,” the ad went on, taking a swipe at the Morning News. The newspaper, Marcus believed, had agitated for right-wing causes to the detriment of the city. “Let’s have more ’fair play’ for legitimate difference of opinion, less cover-up for our obvious deficiencies, less boasting about our attainments, more moral indignation by all of us when we see human rights imposed upon,” Marcus wrote.

Marcus received scores and scores of letters, most of them positive. A few weren’t happy with him pointing out the significant difficulties Dallas still faced, such as its “slum problem,” and a handful canceled their Neiman Marcus credit cards. But most of the disgruntled shoppers later quietly renewed them.

After the assassination, the rancorous spirit of right-wing paranoia loosened its hold on Dallas. Certainly grief was a part of it, but Marcus also thinks that the influx of educated people who moved to Texas as it shifted from an oil-based to a technology-based economy in the ’60s had a major impact. “Education allows people to look at problems differently than the ways the native stock was used to doing,” he says.

IN1927, when Marcus went to work for the family store, blacks were not allowed to shop at Neiman Marcus or other downtown department stores. If they did go in and tried on a hat, they might be told, “Oh, that’s $5,000.” It was the way the world worked, and Marcus didn’t notice anything unusual about it.

“I had been born and brought up in Dallas, and until I went to college, 1 had all the prejudices of my upbringing,” Marcus says. “The word ’nigger’ wasn’t something people refrained from using. One day my mother or father corrected me, and said, ’Son, we don’t use that word. We say Negro.’ College made me change in many ways. I began looking at customs, cultures, and behaviors not as God-given, but challenging them. I realized not only did race relations need to be changed, but that change was the mainspring of life.”

Still, it would he many years before Marcus quietly moved to change the store’s policies regarding blacks. In the 1940s Neiman Marcus hired blacks to work as maids, porters, doormen, and elevator operators, but there were no black tailors, salespersons, or department managers.

Joe D. Diggs went to work for Neiman Marcus in 1952 as a porter to the display manager. Diggs had a college degree, but he didn’t want to teach school, one of the few professions then open to black men. His aunt had been hired as a saleswoman, but at the time there were no black salesmen. Blacks could not eat in the Zodiac Room restaurant; there were separate cafeterias for white and black employees. And few blacks even attempted to shop at Neiman Marcus. When they did, they were not allowed to look through the racks; instead they would be taken to a dressing room and brought things the salesperson thought they might like.

In the store, Diggs often saw Mr. Stanley, who would always speak to him pleasantly. After a few years, Diggs was promoted to assistant to the director of the men s display department. Then, during one after-Christmas sale, a store executive came to the men’s department to exchange a gift shirt. All the salesmen were busy, so Diggs helped him find the right size. That afternoon, the executive called him to his office and asked him to become a salesman.

He started working in the men’s shoe department in 1958, but Diggs, feeling he couldn’t speak very well, was more comfortable in the stockroom than on the selling floor. One day, his manager told him Mr. Stanley was in the department and wanted Diggs to come sell him some shoes.

“I went out and sold him some shoes, and I figured if 1 could sell Mr. Stanley shoes, I could sell anybody shoes,” says Diggs. Later, he realized he’d been set up by Marcus, who wanted him out of the stockroom. Diggs was on the selling floor from then on, and he was very successful. In 1977, he was hired away from Neiman Marcus to sell Cadillacs for Carl Sewell. “If it hadn’t been for Mr. Stanley, I wouldn’t be where I am now,” Diggs says.

But though Neiman Marcus began opening up more employment opportunities to blacks, the store, like others downtown, still did not welcome black shoppers with open arms. That didn’t happen until a group of blacks organized a boycott of downtown stores in the late ’60s. Dallas schools and hotels were also feeling the pressure to desegregate. The boycott had barely been announced when Marcus proclaimed that blacks were welcome to shop at Neiman Marcus.

“My brothers were in complete concurrence with me,” Marcus says, “but the store manager, a fine man, said ’Stanley, you’re going to destroy your store. People will close their accounts. They’ll abandon the store.’ “

But Marcus refused to back off.

Though the change was inevitable, a remnant of Dallas still resisted. Marcus remembers that after he opened the store to black shoppers, he was eating lunch at the Zodiac Room when a longtime customer, a white woman, brought him her Neiman Marcus credit card cut in half. “I’m closing my charge account,” she announced. “I’m sorry you feel that way,” Marcus said. Three days later, the woman reopened her account.

In fact, only three people closed their accounts as a result of Marcus’ decision. There was little opposition to integration in the shopping realm. “The public was way ahead of us,” Marcus says.

Wes Wise points out that Neiman Marcus was one of the first major Dallas businesses to put blacks in visible positions. “He was a very gutsy gentleman,” says Wise, who became mayor in 1971, around the time of the boycott. “He seemed to have the courage to do that even if it hurt his business.”

Through it all, Marcus remained the cos-mopolitan. Wise remembers the early 70s, when Marcus invited him to greet Prince Rainier and Princess Grace at the Neiman Marcus Fortnight celebrating Monaco. Marcus introduced an awed Wise to the elegant Princess Grace as “a fellow maverick.” “I was struck by the fact that he was so at ease, so able to move in their world, so completely sincere,” Wise says.

Not long after the black boycott, Marcus took a step beyond merely complying with the law. Several people were urging Eddie Bernice Johnson, one of the organisers of the boycott, to run for political office. But Johnson, a nurse at a Veterans Administration hospital and a federal employee, was prohibited from running. Seeking a new-job, she was given the names of local employers who might help. The first name on the list was Stanley Marcus.

Johnson had never met Marcus; all she knew about him came through a member of her church, a man who had retired after spending many years as a doorman for Neiman Marcus. Every year, he would go down to the store and Mr. Marcus would give him a new suit.

Marcus hired Johnson in 1972 on the condition that she run for public office. That year, she was elected to the Texas Legislature. She worked at Neiman Marcus until 1975, when she went back to college. Marcus remained a supporter over the years. “He was one of the original persons in Dallas to be supportive of women candidates,” says Johnson, who is now a member of Congress from Dallas.

Marcus’ bravery and adventurous spirit have not dimmed with age. Liener Temerlin remembers that when Marcus was 75 years old, they were in Antigua together for a seminar. The always punctual Marcus was late to give a speech. Why? He’d been taking snorkeling lessons. For his 80th birthday, Temerlin gave Marcus a day at the Ringling Brothers Circus in New York. For one day, Marcus did every job in the circus, from shoveling elephant droppings to playing ringmaster in front of a packed house at Madison Square Garden.

“He is without a doubt the youngest man I know,” says Temerlin. “He rarely talks about the past, only if you ask him. And if you do, he has total recall.”

This month, designers from all over the world will make a pilgrimage to Dallas to honor Stanley Marcus. A gala birthday party will be held at The Store downtown, There, visitors will cross Marcus Square, where four markers praise Mr. Stanley: “Prospective of Truth, Legacy of Wisdom, Commitment to Quality, Spirit of the Arts.”

“It was a different world,” says A.C. Greene simply. “Stanley stuck out above that world altogether and eventually, the hulk of us finally caught up with him. We all moved, and finally reached the point Stanley had been at all those years.”

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Local News

In a Friday Shakeup, 97.1 The Freak Changes Formats and Fires Radio Legend Mike Rhyner

Two reports indicate the demise of The Freak and it's free-flow talk format, and one of its most legendary voices confirmed he had been fired Friday.

Local News

Habitat For Humanity’s New CEO Is a Big Reason Why the Bond Included Housing Dollars

Ashley Brundage is leaving her longtime post at United Way to try and build more houses in more places. Let's hear how she's thinking about her new job.

By Matt Goodman

Sports News

Greg Bibb Pulls Back the Curtain on Dallas Wings Relocation From Arlington to Dallas

The Wings are set to receive $19 million in incentives over the next 15 years; additionally, Bibb expects the team to earn at least $1.5 million in additional ticket revenue per season thanks to the relocation.

By Ben Swanger