ON THAT LAST SUNDAY, DE-cember 8, 1991, when the staff gathered to put out the final edition of the 112-year-old Dallas Times Herald, there was a remnant of familiar routine to carry everyone through a very difficult day. There was, after all, one more newspaper to get out.

Assignments were given. Orders barked. Meetings held. Decisions needed to be made, including one on what size type the paper should use the next morning to announce its own demise. But that was a problem.

Loyal Times Herald readers had become somewhat inured, even deadened, to the appearance of huge type on Page One in the last year, especially during the Persian Gulf war.

Desperate to punch up the street sales, in order to make the paper look viable to potential buyers, management had called for bigger and bigger Persian Gulf war headlines every day-most of them written in a kind of macho sporting tone, as in “WE POUR IT ON!”

I worked in the lobby, in a poorly lighted, poorly heated makeshift arrangement of partitions, occupying space that previously had been home to the “Times Herald Museum.” We were the editorial board-12 strong in 1987 and now down to two writers and three editors. Our unspoken mission, like that of everyone else in the building, was to use whatever combination of smoke and mirrors it took to help convey an impression of vitality in a dying newspaper. Our boss, editorial page editor Lee Cullum, had an office on the other side of a glass wall at the back of the lobby, in the plush blue-carpeted region occupied by the publisher, the president, the head bean counter, the head salesman and Mamie Harris (the long-term executive secretary who was the corporation’s sole repository of institutional memory).

Together, we in the lobby and Lee in the blue area were a non-management body whose mission was to put out the editorial and opinion pages. But we also served as a convenient shield for the real power wielders at the paper. When they did not want to talk to someone, they sent him to us. In order to maintain the fiction that we were people worth talking to and thereby use us as their shield, the power wielders had to allow us to hold our seances with people in their own impressive blue-carpeted area.

When delegations arrived to meet with the editorial board, we lobby dwellers tried to assemble on the carpeted side of the glass wall ahead of time or after the visitors already were seated in the board room with Lee, so that they wouldn’t see the humble circumstances in which we really worked. We considered it to be a matter of credibility.

The arrangement meant that we editorial department workers always were trekking back and forth through our little mouse hole in the Berlin Wall between the ownership of the newspaper and the wretched stafflings in the rest of the building. Inevitably, we saw and heard all of the things we wanted least to know.

During the Persian Gulf war, there was a giddy, nervous, pasty-faced kind of exulting going on within the inner sanctum because of the initial spike in street sales. We smiled when we were among them, on their side of the glass, because it was a time when a failure to smile could be fatal.

When we gathered in our gloomy. Dickensian lair in the lobby, we tried to keep spirits alive with black humor. One day the giant headline was, “THEY’VE GOT OUR GUYS!” The next day, when American female soldiers were captured, we wondered aloud if the headline on the street edition that afternoon would be, “DANG! NOW THEY’VE GOT OUR GALS!”

But we could feel the combined effect of the gloating and the bizarre headlines in the pits of our stomachs. Those headlines, we all knew, were the death rattle.

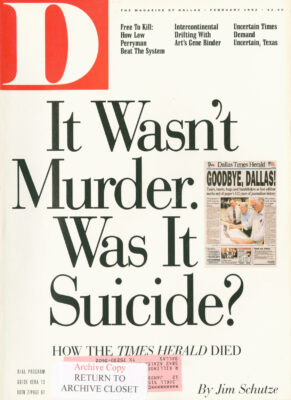

In the end, on that final Sunday, a decision was made to announce the paper’s demise in a headline (hat was almost moderate, given the recent typeface binge. The front page on Monday said, “GOODBYE DALLAS!” in letters that were only 2 3/4 inches tall-larger than you would use to announce that Hitler had been found alive but smaller than required to declare that the planet was about to explode.

The Times Herald’s last gasp was so predictable-not with a bang, not with a whimper, but with a monster headline-that one could not help wondering if it was all preordained from the outset.

Among the Herald staffers, the babies and the come-lately’s had no way of knowing. They thought The Dallas Morning News had reached out in sheer malice to smite us. When I talked afterward to people outside the business, the last major newspaper event most of them remembered was the great comic page heist, in which the News had expropriated all the hot comics and most of the good syndicated features from the Herald. Some of them thought the News had hectored us into the grave unnecessarily,

My conversations with sympathetic people outside the business have been difficult. And awkward. 1 know that they mean well. But I am one of the few who was there, inside, for the whole ride. I do know what happened. I do know what it was not. It was not murder. It was one of three things. It was simple defeat. Or it was suicide. Or it was defeat and suicide. But I do not know-or maybe I am still afraid to make up my mind-which of the three it was. I will allow you to do those honors.

Most of what I knew in the final years I found out in the fancy, executive catering kitchen at the back of the blue area. We had to go in there to get coffee and soft drinks for the people who came to meet with the editorial board (a task that had been performed by white-liveried servants in the heyday a few years earlier.)

I went to the executive kitchen one afternoon about a year ago to load up the silver service tray for some guests, and the man who was then president of the company was standing a( a counter stirring a cup of coffee all over the saucer, staring into space and muttering to himself. He whirled on me.

“You were here then!” he said.

They were all aware of that. They knew I was one of the originals. In the double-time parade of owners and executives who had come through in the final years, there was no collective memory at all of what had gone before, of what the Herald ever had been or why it had become what it was. Everyone’s history of the place began the day he showed up for work. But they knew there was a link between me-the tall one with the beard who was older than 22-and the past.

“Yes,” I said. “1 was here then.”

“I just have to wonder,” he said, breathing through his teeth and churning coffee all over the counter, “what in the hell it was like working in a place like that.”

I knew. I remembered what it was like then. But I would never tell. Not him. I would never tell, because it was. . .glorious. The most exciting time of my life. Wonderful. And doomed.

THE CALL WENT ACROSS THE NEWS ROOMS OF AMERICA. I was 32 when it came to me. It was early winter 1978, and I was sitting at my desk on the third floor of the Detroit Free Press building, a Sullivanesque old tower in downtown Detroit that looked like the set for every cornball black-and-white 1930s newspaper flick ever made. Outside on the deep window ledge, partially buried in soot-blackened snow, was a dead pigeon, whose decomposition I had been monitoring since mid-December.

My friend Rone Tempest called. He had left the Free Press a year earlier to go to the Dallas Times Herald. Tempest was famous in Texas newspaper circles the minute he hit Dallas because in order to recruit him, the Times Herald had agreed to pay him $400 a week. It was almost unheard of for any reporter in Texas to make over $200 a week at that time.

Eventually Tempest would recruit a whole mafia of us from Detroit. Detroit was a very tough, competitive newspaper town- the kind of place that developed good foot soldiers. Now, barely a year later, Tempest was calling to tell me he had been made metro editor. He was breathless. It was an ascent that would have taken between five and 10 years at a normal newspaper.

“Schutze!” he said on the phone that day. “What do you want most to do in the world?”

Easy. He knew. I had a lifelong, obsessive, counter-intuitive and consuming desire to be a cityside columnist, writing about the heartbeat of a great American city. For a year now, whenever Kurt Luedtke. the editor of the Free Press, found himself trapped alone on an elevator or at the bar with me. he would always open his part of the conversation by saying, “Hi, Schutze, you can’t have a column.”

And now, here it was on a platter, my dream, in a place called Dallas, at a newspaper that was beginning to make a major name for itself.

Tempest said, “Come on down here, be a reporter for a few months, and you’ll probably have your column handed to you.”

When I came down to be wooed, they showed me a huge, new Chevrolet with an actual working telephone inside and said, “This, of course, will be your company car.”

After I had been at the Times Herald a month, I asked Tempest where my company car was. He said, “You mean the company car?”

Oh, well. It was a newspaper war. In a war, commanders must do what they must do.

There was not always a war, of course. Before the war, there was peace. In the 1960s, the Dallas Times Herald and The Dallas Morning News had worked out a convenient and comfortable modus vivendi. The Morning News was the newspaper of choice among the city’s wealthier and more conservative readers, and the Times Herald owned the more blue-collar end of the rainbow. They nipped and tucked around each other in terms of readership, one taking the numerical circulation lead for a while, only to be passed again later by the other. But each company took in exactly half of the advertising money spent in Dallas each year; of every dollar spent on newspaper ads, the Herald wound up with 50 cents and the News with the other 50. That was before the Times Mirror Corp. came to town.

Times Mirror, owner of the Los Angeles Times, was literally bursting at the seams with cash in the late 1960s. Otis Chandler, the towering, square-jawed surfer prince of the family, came through Texas on a shopping trip with an entourage of similarly large, square-jawed, sun-kissed men, looking for things to buy.

Chandler signed a deal with the owners of the Herald by which his company acquired the Dallas Times Herald, KRLD Radio, KRLD-TV (now KDFW-TV), a small offset printing company, several parcels of downtown real estate and a huge pension fund, paid for in Times Mirror stock worth under $100 million.

The deal was consummated in 1970. At that time, five-year contracts were signed with the key Times Herald managers, guaranteeing them their jobs and allowing publisher Jim Chambers, editor Felix McKnight and others among the local sellers to assure their friends on the Dallas Citizens Council that the new ownership would produce no significant changes in the paper, allowing it to mumble along forever in its familiar role as one of Dallas’ two equally somnolent, harmless newspapers.

The year when Times Mirror would be free to make changes was 1975. In 1974, the paper’s financial performance was respectable: It chalked a pretax profit of $3.2 million on revenues of about $34 million.

But the people at Times Mirror were beginning to look at Dallas and see much more than a bank account. If anything, they heard a nimble deep down in the earth and smelled a dust on the wind that would have meaning only to people who had lived through a continental land rush themselves.

The word “Sun Belt” was not quite yet in widespread use, but the numbers on the demographers’ spreadsheets and charts already were overwhelmingly clear for the decade ahead: hordes of extremely desirable middle-class migrants were headed straight for Dallas.

It was a newspaper marketer’s most unutterably delicious dream. Marketing people claim that newspaper loyalties are harder to break than political party affiliations. Lifelong readers of one newspaper in a competitive market almost cannot be forced at gunpoint to switch papers.

But here, on its way into town with a roar and a rumble, was a multitude of the very people the ad-buying retailers wanted most to draw into their stores. And these people had no loyalty to anyone. They were ripe for the plucking.

The Times Mirror strategy for Dallas was simple, brutal and daring: Ride in hard, shoot up the place, get the attention of the greenhorns before they have time to settle in and sign those dudes up.

In the absence of a newspaper war, both Dallas dailies were in positions that probably would have been tenable for a good long time. Once a war started, however, the Times Herald was in an extremely disadvantageous position in the marketplace. A demographic pox had been killing off blue-collar afternoon dailies one after another, beginning in New York in the 1960s, moving to Philadelphia in the early 1970s and then marching out across the land. The Times Herald was a prime candidate for the disease.

But if the paper could grab the greenhorns quickly and sign them up as subscribers, it might be able to pull itself up on their backs into a more affluent subscriber base-more attractive to advertisers-and then use the income to finance a transition to the healthier morning newspaper cycle.

The window of opportunity was clear but tiny. It had to be done before the settlers had time to get the idea that The Dallas Morning News was the upscale paper. It would take tremendous concentration and discipline to pull it off.

In the process, the Dallas Times Herald and the Times Mirror Corp. intended to kill The Dallas Morning News dead. If their plan had worked-and, for a while, it almost did-then the people sobbing and trundling their boxes to the curb through a gauntlet of cameras would have been the employees of The Dallas Morning News.

Once the war was started, somebody had to die.

And don’t imagine for a minute we did not have a thirst for blood at the Times Herald then. It was what brought us here. The new editors at the Times Herald-editor Ken Johnson, who came from The Washington Post in 1975 to be the general, and managing editor Will Jarrett, who came from The Philadelphia Inquirer in the same year to be his colonel-put together in 1977 and 1978 a news room that was exciting, tense, mean, funny, crackling, explosive-full of people who wanted to fight, wanted to win, wanted to see somebody else go down, A day in the Times Herald news room in 1978 was like a year in the news rooms of most of the sleepy, sober-sided, non-competitive newspapers of the world.

The news room softball team had an incredibly good win/loss record and was possibly the worst thing that ever happened to sportsmanship. I don’t think I have ever seen amateurs use their cleats that way before. One day when Tim Kelly, the assistant managing editor, failed to slide hard enough against an opposing first baseman, Will Jar-rett lost his temper and bounced a full can of beer off Kelly’s torso.

But the chalice was passed at night. We moved en masse, from bar to bar, not a friendly group, reforming our circle at each new fire, passing the brooding wisdom of the pack in hisses and snaps. 1 still remember the moment, in the darkest booth at the back of the back room at Strictly Tabu, when Will Jarrett told me how we would win the war.

Jarrett, a rough-hewn West Texan who had gone East with Knight-Ridder Newspapers to make his name, leaned forward across the table. “Hey.” he said, one eyebrow rising roguishly over his right eye, a sly, wind-raked grin splitting his face, “if you’re the new guy in town, and you want to be taken seriously, what do you do? You look for the biggest guy in town, you go up to him and you kick him right in the balls.”

I still think it’s a great philosophy of competitive newspapering. I am told it’s also the prevailing philosophy of most new arrivals at prisons.

And we did it. In 1978, when I was doing some investigative reporting, I found out about a city audit report that had been suppressed. I demanded that it be turned over to me. Pushed to release it by the city attorney, then-Mayor Robert Folsom handed me the report in a sealed envelope and told me to take it to Ken Johnson. Folsom said he would come to the newspaper the next morning and explain why the story I was about to write could not be published.

That was how things always had been done in Dallas. Between gentlemen. At the top.

Folsom came in around 10 and met with Johnson and Jarrett. They listened politely to him. Then, lifting up a copy of the Herald’s still relatively new morning edition, Johnson displayed Page One with the audit story all over the top of the page.

“I guess you don’t read our paper in the morning. Mayor,” he said.

It was the kind of moment we loved. It was the kind of moment that made people hate us.

There is a lot of talk now about the powerful people in Dallas who came to hate us and how much it hurt the paper. In the years after Times Mirror had lost its stomach for the fight in Dallas, the delegations of extremely angry Dallas leaders who trekked out to L.A. to whine to the Chandlers may have become a factor. But not at first, To this day, Ken Johnson is defiant on that score.

Johnson left the Herald in 1983. Last December, a week after the Dallas Times Herald had closed its doors, he talked to me in the vast high-rise North Dallas headquarters of the successful Westward Communications company he and Jarrett founded after they left the Herald. He said, “The Bob Dedmans, the Russell Perrys. the John Scovells-between ’em, they didn’t run a page of advertising.”

It was always about advertising. The only thing advertisers really care about, when all the blarney and bluster is blown off, is draw-the ability of an ad in a particular medium to cause a gang of money-waving, product-buying, non-shoplifting customers to show up the next morning after the store owner’s ad has run.

When the newspaper was strong, and when the top managers were confident and stout of heart, they did not care how many Dallas big shots and sacred-cow-types hated them. As long as the ad dollars were coming in, we staffers never heard a word about the complaints from on high. It did not matter how many pouty muckety-mucks went to Los Angeles to show Mr. Chandler where they had been kicked. Their misery, in fact, was often our readers’ delight.

THE BUSINESS ABOUT THAT COLUMN I was to get a few months after I showed up turned out to be.. what was it Rone said? I think he said it was “complex.” What it turned out to be was two years.

They were great years. I finally got my hands on the damned company car and roamed around Texas for a year or so doing stories and discovering the state. I did some investigative reporting at City Hall with Ralph Frammolino, a young reporter who liked to say, on introducing himself to people, “Some people call me the ’Hitman from Detroit,” but I don’t really like it when they do.”

Frank Clifford was doing superb political reporting for us. He was the first to publicly articulate the whole urban rebirth syndrome that began with The Grape Restaurant and Lower Greenville Avenue. Julie Morris was the single toughest, best, 1930s-style, punch-’em-in-the-face and ask-’em-for-a-statement reporter that Dallas has ever seen. Or will.

I started writing my column in 1980. For the first three years, the column ran on the side or at the bottom of the front page of the local news section. It was an extremely visible place in the paper; I had great fun; and I never forgot Jarrett’s philosophy of jail-house journalism. The only problem was that the ship hit the rocks in ’82.

Before I can talk about what went wrong, however, I have to say what went right. Dallas itself was blowing and going in 1980. The stores were packed; the opera and the symphony and the ballet were sold out; in a city thought of elsewhere as selfish and mean (because of the “Dallas” TV show), huge new works of charity and culture were afoot; and it was our publisher, Tom McCartin of the Dallas Times Herald, who was out there and in it up to his elbows. Under McCartin, the Dallas Times Herald became a major force in promoting minority arts organizations in the city and in promoting the larger concept of a pluralistic and tolerant city.

If The Dallas Morning News now owns Dallas for the long sober haul, at least the Dallas Times HeraId owned it for the binge. In 1977, the Times Herald actually nipped ahead of the News in the extremely valuable Sunday circulation figures, selling 322,093 newspapers every Sunday to the News’ 321,167. In the three-year period between 1977 and 1980, pretax profits at the Dallas Times Herald increased by over 100 percent, from $8 million to $18 million.

In that same period, the newspaper was the object of a chorus of praise from national media reporters. It began in 1975. when Newsweek magazine called the paper “one of the best five newspapers in the South.”

Between 1975 and 1985, the Dallas Times Herald won two Pulitzer Prizes, fielded nine Pulitzer finalists, won four Picture of the Year awards, two George Polk awards, two national Sigma Delta Chi awards, two Overseas Press Club awards, a World Press Photo award, the George Jean Nathan Award and a slew of others. The sports section was consistently singled out by media critics for its unparalleled sports investigative reporting. Our writers brought several college sports scandals to light, including the debacle at Southern Methodist University. For almost 10 unbroken years, until 1985, the Times Herald swamped the Morning News in literally all of the state contests.

The problem was that, by 1985, the prizes were already meaningless in terms of the outcome. The war was already lost.

THE WORM TURNED IN 1980, WHEN the reins at The Dallas Morning News were turned over to Robert Decherd, the young Harvard-trained scion of the Dealey ownership family. One of Decherd”s first moves was to hire a new editor, Burl Osborne, a combative veteran of the wire services in an era when the AP and UPI were fiercely competitive. Osborne, in turn, began loading the News up with bright young editors from around the country.

In their own descriptions of that history, the News people tend to say now that they did a lot of expensive market studies in the late 1970s and early 1980s, but I think they are modest. I think, because the owners were native, that they knew the big things in their gut.

And if they didn’t there was. at that time, a piece of terrible knowledge, glowing under wraps in the inner sanctums of the city’s establishment leadership. It was invisible to the newcomers and the interlopers, all of whom saw the city of Dallas as a place where the streets would be paved with gold until kingdom come.

In May 1977, Bernard L. Weinstein and Robert E. Firestine, the economics gurus at the University of Texas at Dallas best known for predicting the entire North Texas Sun Belt boom, submitted to the Dallas city manager an uncirculated white paper confirming the worst tears of the city’s old guard leadership. Dallas proper-the city-was already dead.

None of the real growth ahead, they said, was coming to Dallas. The desirable, middle-class, money-spending, school-building, job-spawning growth was headed straight for the suburbs.

Unaware of these projections, in the first three years of the 1980s Times Mirror Corp. made a series of key capital and operating decisions that tied the newspaper’s fate to the city proper. A printing plant expansion was carried out at the old downtown location, instead of in shiny, new, suburban Piano where the Morning News built its own huge new plant.

In order to stay up with the News, the Herald should have invested the money in the 1980-1982 period to create a truly viable suburban morning delivery system. According to Johnson, Jarrett and McCartin, Times Mirror would not allow it. Delivery of the paper gradually became a nightmare. By 1982, the chances of getting a copy of the Dallas Times Herald delivered to your doorstep in the suburbs were about as good as the chances of being struck dead by falling debris from Skylab.

In 1985, Times Mirror finally plunked down a quarter of a million dollars on a market study that told them what anybody on the street in Dallas could have told them three years earlier for free: In staggering numbers, people who quit taking the Herald did it because they absolutely could not get it delivered. And the place where it was least possible to get the paper delivered was in the ’burbs.

During the same period that the Times Herald was bonding itself at the hip to the city, none of the local smart money was making the same mistake. Even the mayor, real estate developer Robert Folsom, was making huge personal investments in suburban land and using his influence at City Hall to ram commuter thoroughfares through the gentrified neighborhoods of the old city.

It would be unfair to conclude that the News deliberately adopted a strategy abandoning the city. But, in working toward a more politically cautious, consumer-oriented mix, the News came up with something that was very accessible to the culture of the suburbs. In other words, the News adopted a strategy chasing the readers, and readers happened to be abandoning the city.

It’s also clearly wrong to imagine the Times Herald took a noble stand to the death in the city’s defense. The Times Herald did what it did because its parent company was too quick to take millions of dollars in operating profits out of its Texas properties. The Herald got stuck in the city. Otherwise the paper would have traded its city circulation for the ’burbs in a flash.

It was great for me. As a writer, what I You have to like a swamp-country roadhouse where you can jump right into happy hour bonding. In this case the tail end of some sharing between a big ol’ boy with wrists the size of your neck and a grizzled graybeard on the adjacent stool. “I can weld anything from a broken heart to the crack of dawn,” the big guy declares. His friend nods, or perhaps teeters, in affirmation. In an instant, you revise your ambivalent expectations of a weekend in Uncertain, Texas. Too bad you’re laughing. Which, fortunately, gives you another reason to like Uncertain. “Bones” Brown, the guy with the confined to the circulation department. Years later, when the new president asked me how on earth a certain hiring order could have stayed in effect for four years after it was supposed to have been rescinded, I remembered how money had sloshed around the building under Times Mirror.

A friend of mine came to work at the Times Herald as an editor in 1983. It was a time when few reporters had credit cards and most of them traveled and worked on cash advances from the company. Not long after my friend showed up, some of the reporters under him started coming to me and saying, “Boy, your pal is sure a pain. He won’t give us any cash advances.”

I asked him about it over lunch. It was the first of many such conversations I had with him and other managers in which my lunch partner would first look over his shoulder, scan the tables behind and then lean forward to whisper a response.

“Schutze,” he muttered, “I checked out the petty cash deal here my first week, There’s a woman downstairs who hands it to you by the fistful out of a box. I asked her about an accounting trail, and she wasn’t familiar with the term. I’m not touching that money with a 10-foot pole.”

My father sent the paper a check for over $100 in order to have the Times Herald delivered to him by mail in Nashville. The paper never showed up, and he couldn’t get any satisfaction by mail or on the phone. Finally he asked me to help.

I spent the entire morning searching, and finally, in the gloom at the back of the huge room where the folding and bundling machines were, I found the person in charge of mail subscriptions. She was sitting beneath an unshaded light bulb hanging from an extension cord in a little Sheetrock sort of a cubbyhole with dirty steam pipes across the ceiling. All around her was a snowdrift of dust-darkened correspondence.

I explained my problem. She said, “Well. Honey, if you work here, we’ll just send your daddy the paper and don’t worry about it.”

I thanked her. But, knowing my father’s meticulous habits where money is concerned, I asked her what might have happened to his check for over $100.

She shrugged and gestured around at the stacks of envelopes and checks on her desk, on the floor, on empty chairs and in cardboard boxes. “Just don’t worry about it,” she said.

It was at about that time that my copy of The Dallas Morning News failed to arrive as usual on my doorstep one morning. It had never happened before. I relished the opportunity to call up the News and yell at their people instead of my own.

The woman at the News said, “What are the last live digits of your telephone number?”

Computerized database systems were still very new then, and I literally had no idea what she was doing. I really thought it was some kind of contest or lottery. I gave her the last five digits.

She said, “Oh. yes, you’re Mr. Schutze on Bryan Parkway. and you take the paper on weekdays and the weekend, We’ll have it right out to you.”

It hit my porch half an hour later. I was so depressed. I couldn’t move for hours. None of the sloppiness at the Herald had mattered when we had been winning, when the cash and the prizes had been rolling in the door every day faster than we could count. But now, every leaky joint in the system was an ugly lesion, bleeding off our last waning chances at survival.

IN 1982, THE TIMES HERALD SUFFERED an outbreak of internecine samurai war-tare among the top managers. It started when a new. young managing editor, Jon Katz. went to L. A. and told Otis Chandler that the newspaper war had not been won in Dallas, that the Morning News was a very hot paper and that the Times Herald was in a mess.

Partisans on one side argued that Katz had carried the bad news to Chandler only because he and Tom McCartin were conspiring to force Ken Johnson out. On the other side, the partisans said that Katz was telling the truth at a critical moment, when the truth might have saved the Herald. In the Stalin-esque purge and counter-purges that ensued. I saw a whole bunch of people, including many noncombatants, badly hurt-some driven out of town penniless and humiliated.

I have no idea who was right and who was wrong. But the warfare itself was a spectacle so bleak, so debilitating, so utterly demeaning of all the participants, that I firmly believe it broke the paper’s back forever.

The amazing thing for me, in doing the research for this article, was the discovery. these many years after the wars, that the samurai themselves had never even noticed what their blood baths did to us peasants, Katz is the only one who has some perspective and some soul (and some guilt, which we writers always like). But the rest of them snap and growl when they talk about it.

All I know is that we hated both sides. We hated them because they left us. We saw what they no longer cared about: that they were allowing the ship to drift to the shoals, while they staggered around the decks in the night, grunting and hacking each other apart.

Anybody who had any snap left the paper for higher ground during that period. I stayed, even though the ground was giving way. I called the Herald the “Children’s Revolutionary Newspaper” in that period because we children put it out while the adults were off killing each other.

On any given day the Times Herald was still capable of brilliance. The next day it would be worse than the worst college newspaper in the country. It reeled and stumbled from design to design, personality to personality, because there was no one at the helm.

I wrote my column every day, hit a button on the computer and sent it straight to the back shop. No one ever read it before it was published because it was in no one’s interest to read it.

I carried out an experiment one day-a cruel trick, really, on a newcomer. I knew him from Detroit. I was trying to explain to him what the paper was like. He refused to believe me.

I said, “Come on.” I led him up to the city desk. There were six or seven assistant city editors, a city editor and half a dozen people with the words “managing editor” somewhere in their titles sitting around the desk.

I harrumphed for attention, then said, “I have written a column for tomorrow’s newspaper that I am worried about. It’s a fairly personal attack on a wealthy and powerful citizen of the city, known to be litigious, and I fear that it may be libelous. I worry that the column, in its present form, may harm the paper. Would any one of you be willing just to read behind me on it before I send it to the printers?”

No one moved. There was a long silence, They all kept their eyes glued to each other or to their computer screens. I refused to move. I waited. Finally one of them whirled around and held up his hands before his face with the two index fingers crossed, in the gesture used to ward off vampires.

No word was spoken. I returned to my desk. My friend, the newcomer, sat down heavily next to me. He whispered, “I think I have made a very serious mistake by coming here.”

There was a time after the samurai wars, in the early ’80s, when the paper almost tried again. Times Mirror agreed to pour in new money briefly and gave the go-ahead for a huge hiring binge. But the brave new spirit was short-lived; the hiring binge was supposed to have been called off only months after it was launched, even though the bosses forgot to tell the department heads about it; and from then on, even the paper’s best efforts were transparently desperate. Smelling weakness, the paper’s enemies- and even its friends in the black community-closed in on it, leaping at its sagging shoulders for blood.

Live by the sword, die by the you-know-what.

Once the revenues drooped, the editors were less able to defend us foot soldiers from the Dallas establishment’s heavy artillery. Independence costs money, In 1984, the paper finally gave in to critics of me and Molly Ivins by kicking both-of us off the metro front. Molly was still allowed a fairly visible slot on the Op Ed Page, but she had to move to Austin and stop writing about the kind of people in Dallas who were only a two-bit phone call away from the publisher.

I was given the practically invisible slot at the bottom of the editorial page. A friend of mine in management explained: “They would like to fire you to make amends with the business community, but this is a bad time to ditch your East Dallas readers. What they hope to do is wait for fewer and fewer people to read you. and then they’ll fire you. unless Providence intervenes and you get run over by a bus first.”

Under the circumstances, I took it for a vote of confidence.

Management, meanwhile, had begun a process that continued almost to the very end at the Herald, of putting new kick-’em-in-the-balls columnists out front, waiting until the heat built up to a certain point and then killing them off. The lifespan of a Times Herald metro columnist toward the end of the war was that of an Italian second lieutenant in 1943, Laura Miller was the most recent victim. The most public (and damaging to the paper) was John Bloom, who was fired over one of his “Joe Bob Briggs” columns. I think the shrewder eyes in the public saw through the Joe Bob incident, saw what the paper was doing. They saw how the paper pretended to champion diversity and eccentricity but actually had begun using up local columnists like Kleenex, hoping to use flash to camouflage the absence of any consistent quality reporting.

I had worked from home for several years, but I was called back into the office three years ago, told that I had to work downtown, write editorials and attend make-believe meetings with people. It was not a promotion. A better man might have snatched up his Rolodex and stalked off looking for love, understanding and a pay raise at that point.

But I could not leave the column. My friends and intimates in early adulthood had been my fellow newspaper people. I had long since stopped going to bars and had become far too cautious about things in the building ever to confide in any of my co-workers. In Dallas I had my wife, my son, my parents and in-laws, my friends in the best neighborhood I had ever occupied in my life. But, beyond that, the major personal relationship of my life was the one I had with the city through the column, and 1 could not give it up.

I don’t mean to give short shrift to the brave souls who followed the Times Mirror Corp. after it sold out in 1986. Roy Bode, the last editor, fought valiantly to put out a real newspaper with a make-believe staff. And he had some great days. If they had asked me to write Bode’s last headline, it would have been about 10 inches tall, and it would have said, “AAARGH! YA GOT ME!”

Dean Singleton bought the paper at a fire-sale price in 1986, got a better deal on newsprint, started discounting the heck out of the ads and made some money. He sold in in 1988 to John Buzzetta, an honest man and a much sounder businessman than anybody who had been at the helm before him. But Buzzetta got taken. The place was already a goner when he bought it. He was very decent in his treatment of us at the end-far more responsible toward the employees than the Times Mirror people were at the end of their regime, I used to stand in that little kitchen and watch all those intense, earnest, well-meaning, smart young guys who worked for him eating their guts out, trying to figure out why they couldn’t get the nose up no matter what they did.

What could I say? Hey, I’m sorry. We had a great time around here, a long time ago. Sorry you lost your shirt.

WAS THE HERALDS DEATH PREOR-dained? I still don’t know. Sometimes I think it was. Our eventual defeat may have been written in the spirit, the morality, the prize that brought us all here for the war in the first place. But then that kind of deterministic analysis lets people off the hook for their personal responsibility in the situation, doesn’t it?

People at the Times Herald always thought of the newspaper war in terms of the game- the newspaper game, the corporate game. People talked about “the play.” What will their play be? What will our play be? I don’t think it was play for the News. I think it was soil.

Jon Katz, the former managing editor who blew the whistle and set off the samurai war, is now a novelist, living in the Northeast. He said to me last December, “I don’t think anybody who was there could wash themselves of responsibility. Collectively, we blew the last great opportunity anyone had to keep newspapers competitive. We ended up killing off a newspaper.

“But I hope the right kind of credit goes to Decherd and Osborne at the News” he said. “They were a textbook case of doing it the right way, They never wavered. They never go( caught up in internal wars.”

Former Times Herald publisher Tom McCartin told me a story about something that happened after Katz was gone, in late ’82, when the place was knee-deep in samurai blood and sliding precipitously in the market. McCartin had devised a stopgap plan to slash distribution costs even farther and suspend the last drop of promotional activity. He says now he had to do it to keep L.A. off his back.

He was on his way to the airport to go to L.A. and make his presentation. Whom should he run into at the airport but Robert Decherd, on his way in from some place? Decherd’s wife was parked at the curb, with their little boy in the car.

McCartin walked over, stuck his head in the car and made some joke about “See all these gray hairs your daddy’s giving me?”

The little boy held his foot up in the air so McCartin could see his new cowboy boots.

On the plane, with his notes for the presentation in his lap, McCartin stared out at the clouds. “That’s what Decherd’s play is,” he thought. “It’s that little boy. He’s doing everything he’s doing for a plan that’s 20 years out. And here I am. I’m on my way to L.A. with a brilliant idea to jack a couple million more bucks out of the place for the next quarter.”

He told me he cried at that moment. I believe him. Because I think he cried when he told me about it in December, five days after the last edition had hit the street. I think we both did.

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Local News

In a Friday Shakeup, 97.1 The Freak Changes Formats and Fires Radio Legend Mike Rhyner

Two reports indicate the demise of The Freak and it's free-flow talk format, and one of its most legendary voices confirmed he had been fired Friday.

Local News

Habitat For Humanity’s New CEO Is a Big Reason Why the Bond Included Housing Dollars

Ashley Brundage is leaving her longtime post at United Way to try and build more houses in more places. Let's hear how she's thinking about her new job.

By Matt Goodman

Sports News

Greg Bibb Pulls Back the Curtain on Dallas Wings Relocation From Arlington to Dallas

The Wings are set to receive $19 million in incentives over the next 15 years; additionally, Bibb expects the team to earn at least $1.5 million in additional ticket revenue per season thanks to the relocation.

By Ben Swanger