IN THE MONTHS PRECEDING THE October 19, 1987, stock market crash, Dallas investor Harold Simmons had been conspicuously absent from what he felt was an overpriced stock market. “I always thought you were supposed to buy low in this business,” he explains.

That elemental strategy of “buying low” has helped Simmons, fifty-seven, build an empire of thirty-five companies with combined assets in excess of $3 billion. He’s been called a corporate raider, a financial gunslinger, a ruthless, fortune-grabbing Texan, and much worse. That’s because he buys corporations, usually without the consent or support of management. So his acquisitions are called hostile takeovers, and to some, that makes Simmons a bad guy.

To Simmons, who in the last ten years has booked an average annual return on investment of an astounding 95 percent, it makes no difference what anyone calls him. In the last two years Simmons has been increasing his personal wealth by about $20 million a month. That kind of money takes the sting out of any critic’s barbs.

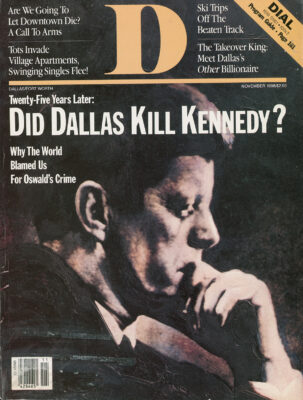

According to Forbes magazine’s 1987 roster of the super-rich, Simmons is now Texas’s second richest man, runner-up to Ross Perot. Yet his deliberately cultivated low profile has made Simmons almost an invisible man in his own community. (In a rare feat of publicity-seeking, Simmons wrote to correct Forbes when it left him off a more recent list of prominent worldwide billionaires.) Despite a career of dazzling success, he is little known here in his home city and to some, his methods remain suspect- Simmons will tell you he’s an investor: analysts say he’s a brilliant guy with an uncanny ability to detect undervalued assets. But managers of large corporations with undervalued stock prices will tell you Harold Simmons and his machinations are the stuff that nightmares are made of.

IN THE SPRING OF 1986 SIMMONS WAS on the prowl, looking for his first billion-dollar acquisition. He had recently sold his 40 percent stake in Sea-Land Corporation at a $90 million profit. With an anticipated $300 million to be received from the deal, Simmons was looking for another company to add to his collection.

On April 29, 1986, a small article in The Wall Street Journal caught his attention. The article explained that NL Industries, a New York-based company, was in the process of restructuring and had offered to buy back its stock for about $15 a share. Sensing an opportunity, Simmons wrote the company asking for current financial reports.

NL Industries is a Fortune 500 company with almost a hundred years of history. Originally called National Lead, NL has evolved into an outfit with two product lines, oil field services and specialty chemicals. The oil field services branch was, in the wake of the oil price collapse, losing serious money- $127 million in the first six months of 1986. NL’s low stock price reflected the widespread perception that NL’s value was fundamentally linked to the declining fortunes of the oil industry.

But Simmons, who generally avoids investing his money in either real estate or oil, saw something else: to Simmons, the chemical division was the company’s crown jewel, its profit center, and the primary enticement.

In early June, Simmons received the NL materials he had requested. After reading the reports, Simmons turned to his Quotron terminal and keyed in NL’s stock code. The trading price was $10.75. An asterisk indicated additional information regarding NL on the tape. The news showed something strange. NL management had withdrawn its tender offer to buy back 12 percent of its own stock, citing poor business conditions.

The more Simmons studied NL’s reports, the more interested he became. He knew that earlier in the year Con-iston Partners, a New York investment firm, had made an unfriendly attempt to acquire the company. That may have triggered NL’s buyback plan to purchase up to 12 percent of its outstanding stock. But to management’s dismay, stockholders jumped at the chance to unload at $15 per share. Fully 70 percent of the outstanding stock was tendered for sale, meaning the shareholders had put NL “into play,” as they say in Wall Street takeover parlance. Simmons explains: “The majority of the stockholders were saying. ’Look, here’s my stock. I’ll sell it for $15. Buy it.7 And management said, “We aren’t going to buy it for $15. Business is bad and it’s not worth that much.’”

On that information alone, every bit of it available to the general public, Simmons entered the market on a buying spree, purchasing 10 million shares of NL for between $11 and $15 per share. A week after Simmons began buying NL stock, he received a telegram from NL management asking him to confirm the rumor that he was accumulating NL’s shares and asking the investor to reveal his intentions. In a two-page letter, Simmons said he had in fact bought 10 million shares and stood ready to buy the balance of the more than 60 million shares outstanding. He reminded the NL directors that 70 percent of the company’s shareholders wanted to sell.

The atmosphere in the NL boardroom at that point was “extreme irritation,” according to former NL president Ted Rogers: “We were incensed because the company was at a very debilitated moment in its history. It has a very rich history and was a very good company. We were incensed that someone was taking advantage of the situation. depriving the shareholders, and depriving the company of its destiny.”

But in the cold-blooded world of corporate takeovers, a public company’s future is a matter of value, not traditions or dreams or destiny. And Wall Street issues an irrefutable report card called the stock price.

Simmons, who has chewed up and spit out a few corporate boards in his time, laughs as he recalls NL’s reaction to his letter: poison pills and lawsuits. The “poison pill” is a device used by corporations as a defense against hostile bids. Called a “stockholder’s rights plan,’” NL’s poison pill was written as an amendment to the corporate charter. The purpose: to make it prohibitively expensive for anyone to acquire more than 20 percent of NL stock in an unfriendly takeover attempt. And the lawsuit warning was a standard defense against uninvited acquisitions. Simmons expected both moves, and he was more than ready to respond.

A week later. The Wall Street Journal reported that Simmons filed suit in a New York federal court seeking to nullify NL’s poison pill. At that time, Simmons still held less than the 20 percent necessary to trigger the pill. Simmons’s strategy was to file suit before NL was able to sue him in a New Jersey court. He believed that his chances of killing the pill were better in a federal court and thought that filing his suit first was “a positive tactical move.”

On July I. Simmons made his boldest move thus far. He bought enough shares of NL to go over the 20 percent threshold, deliberately triggering NL’s poison pill. He calculated the ultimate effect of the pill would be to prevent a “white knight” or friendly buyer from coming to the rescue of NL Industries. By intentionally triggering the pill’s onerous effects, Simmons had made it vastly more expensive for any new investor-not just Simmons-to acquire a position in the company. Using NL’s own weapon, Simmons had in a single stroke eliminated any possible future competition for the NL acquisition.

The next day Simmons raised his bid from $15 to $15.125 for the remaining NL shares. In a letter to the NL board, he asked them to drop the poison pill and facilitate a friendly takeover. The board answered with a cannon shot, announcing plans to spin off 20 percent of the chemical division to the NL shareholders in an obvious attempt to increase the shareholders* values and stop Simmons.

IN A NEW YORK TIMES INTERVIEW ON July 9, Simmons said he believed poison pills were illegal and predicted his suit against NL would be successful. He argued that poison pills illegally conferred special privileges on some stockholders at the expense of others. With NL’s poison pill, all shareholders except Simmons were to be given a chance to buy stock at half price once Simmons went past 20 percent. When and if that happened, Simmons’s stake in the company would be drastically reduced.

NL then made another blunder in its anti-takeover defense. It attempted to spin off its highly profitable chemical division to NL’s shareholders, which would have broken the company into two separate entities.

Simmons alone recognized that the poison pill was not NL’s ace in the hole, but in fact (he wild card in his own bid for control. He had studied the terms of the poison pill, which said that no one, not even management, could sell off more than 50 percent of the company’s earning power. Since NL was in the red at that time, it had no earnings whatsoever. It had escaped everyone-except Simmons-that any earning power was more than 50 percent because 50 percent of NL’s earning power was zero.

“In spinning off the whole chemical company, NL played right into my hands,” Simmons says. “If they had been able to spin off 20 percent they may have been able to create an artificially high market on the shares and thereby increase the market price. But when they had to spin off all of their best property, the exact reverse happened, making it easier for me to buy control.”

When the new shares began trading, NL preferred sold at approximately SI2 per share while the common stock traded for S3 and change. The spinoff had not increased values for the shareholders. One more defeat for NL’s management.

In mid-July, in full-page ads published in The Wall Street Journal and The New York Times, NL pleaded with its shareholders: “We urge you not to tender any of your NL securities to Mr. Simmons. We believe they are worth more than he is offering to pay.”

The irony of the ads made Simmons laugh. After all, just one month earlier, NL directors had refused to pay the $15 the majority of shareholders were willing to accept.

While the next ad was being prepared, NL shareholders were notified that NL’s president, Ted Rogers, had offered Simmons a seat on the NL board if he would agree not to purchase more shares. During trips to Dallas, Ted Rogers offered the chemicals division to Simmons for $1.05 billion. Simmons, smelling blood, rejected both offers.

In early August Simmons continued his bid for NL shares while awaiting a ruling from the federal court on the legality of NL’s poison pill. On Wednesday, August 6, Judge Vincent L. Broderick invalidated NL’s poison pill, calling it an “illegal device.”

But Simmons ran into another roadblock. The next day he was barred by the second U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals from buying additional NL shares pending the court’s ruling on the company’s appeal, filed immediately after Brodericks ruling. Then, early on August 8, the Court of Appeals ruled in Simmons’s favor, freeing him to buy more NL shares. He quickly negotiated the acquisition of 18 million shares of NL’s stock at a cost of $4.50 a share, or $64 million.

Simmons’s speed and decisiveness once again caught NL management unprepared. The last-ditch effort to stave off Simmons not only failed, it was a multimillion-dollar backfire. Two months after he first received financial reports from NL, Harold Simmons became owner of more than 51 percent of the company’s shares. Simmons paid $257 million for control of NL, substantially less than the $900 million he originally tendered for the company.

The acquisition of NL was vintage Simmons. He did it his way-alone. But, for better or worse, he had opened the door wider for other unfriendly takeover attempts. A New York analyst with a major brokerage firm reflects on Simmons’s victory: “Each year in New York a highly touted takeover seminar is conducted. All the big guns, like Carl Icahn and Irving Jacobs, are invited. They study the NL takeover as the case where someone got around the poison pill. Harold was calm enough to assess the exact extent of the pill, steer it to the right court, get an advantageous ruling, and then leap forward and buy the stock. He’s making a billion dollars in a year and a half.”

BUT THE LARGER QUESTION REMAINS: what to make of Harold Simmons? Is he a lone wolf or a lone ranger? A predator or a creator of wealth? There’s no clear-cut answer.

Leigh Trevor, a former anti-takeover lobbyist, maintains that corporate raiders are bad news for the U.S. economy. “Hostile takeovers have been very destructive to the country, generating ill effects on companies, jobs, and communities,” Trevor says. But John Peavy, chairman of SMU’s Department of Finance, has an opposite view: “The empirical evidence from takeovers shows they clearly provide money to stockholders. The evidence is overwhelming that takeovers are beneficial.” Peavy adds that it’s usually a company’s own fault if it becomes a takeover target. “The only companies that are targets for takeovers are the ones that can be made more efficient. Otherwise, they’re not going to be selling at low enough prices to make them worthwhile.”

Simmons believes NL’s negligence made the company vulnerable. “It was their fault. They suffered big losses in the oil services area and were too slow to cut them, and too comfortable to restructure.” But former NL Industries president Rogers says management was making exactly those changes, but Simmons denied them the time to realize their effects. “We cut 19,000 people, 14,000 of them in a twelve-month period,” says the former NL president.

Leigh Trevor rejects the “sick man” analysis of takeover targets. “Modern takeover targets are not companies that need to be shaken up, but indeed very successful ones,” he says. “Pro-merger advocates look at stock price performance over a short period of time, but if you look at a longer time horizon, like two or three years, the price increase benefits vanish.”

A 1987 study by SEC Commissioner Joseph Grundfest argues that merger and acquisition activity conservatively added $167 billion to the U.S. economy between 1981 and 1986, but Trevor maintains that losses in the equity markets wiped out more than that amount on October 19. “And we’re left with all the negative effects.”

So is Simmons a miracle worker with the companies he acquires, making them more efficient and productive? A Forbes writer described Simmons’s balance sheet as “hardly star quality” and speculated that “Maybe Simmons is just too busy scouting new investments to keep careful track of all the companies he controls.” Joe Gomes, an analyst for 13D Research Services in York-town, New York, cuts to the core with his views: “If you look at his operating companies, they’re no great shakes. They’re not making a whole hell of a lot of money. But I’d rather see my net worth go from $25,000 to a billion dollars than be able to say my company makes earnings of such and such.”

A few small clouds linger on Simmons’s otherwise sunny horizon. In late September, it was revealed that the Justice Department was looking into charges of price-fixing by NL Industries. Most of the alleged incidents occurred before Simmons bought NL. Also, the SEC announced it was investigating the trading of stock between Simmons’s privately held Contran Corporation and his holding company, Valhi, during the spring of 1987, when the two companies were considering a merger. The merger has not been completed, but Simmons hopes to consummate the deal before the end of 1988.

But a look at Simmons’s parent conglomerate, Valhi Inc. (NYSE: VHI), composed of the various companies he’s acquired over the last fifteen years, will show that Simmons has little to apologize for. Valhi was ranked by the Dallas Times Herald as the top stock performer of all Dallas-based companies in 1987, with a stock price increase of 172.4 percent.

So Harold Simmons will happily leave the debate over the virtues of takeover activity to others. He’s going shopping. The only item on his list is a deal worth at least two billion. And, oh yes, he hopes his target has a poison pill ready.