Hard-news journalists have a history of turned-up noses when it comes to sports staffs, known in the trade as “the toy department.” But every newspaper survey taken during the past ten years indicates that Dallas readers reach first for two sections-sports and business. So newspapers do not operate sports sections haphazardly. It is a cold, serious science these days. The best sportswriters are among any newspaper’s top-paid reporters. Many of them are carpetbaggers, staying at one newspaper a couple of years, then moving on to a better paper or a better beat for better money.

The trend in sports writing today is toward brief, objective game stories, plenty of charts and agate, plenty of facts, and a few features. It is largely left up to the front-page columnist to provide the meanings behind the stats, the day-in, day-out opinions. The columnist is the one who must make you think, make you feel, make you understand, make you laugh, perhaps make you cry.

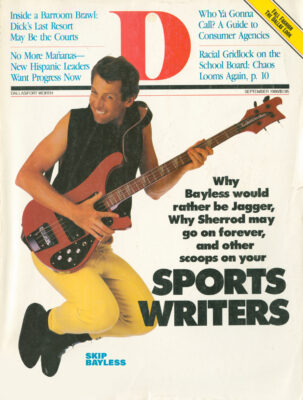

In Dallas, five men are charged with those demanding tasks: at the Dallas Times Herald, they are Skip Bayless, the city’s strangest off-Broadway, box-office attraction; and Frank Luksa, a dry-witted storyteller and newcomer on the block at age fifty-one. At The Dallas Morning News, the front-line columnists are Randy Galloway, who would rather be a hammer than a nail; David Casstevens, a clever, sensitive observer of sports; and Blackie Sherrod, probably the most famous name in Texas newspaper sports-writing history. These five tell you what your heroes are like. Here’s what they are like.

I don’t have many close friends. I’m real private and shy, andpeople don’t know me. I look conservative because I feel youneed to look good in this job. You need to have a neat appearance. But my writing is pretty insane a lot of times, andI’m probably pretty insane. I’m a frustrated rock star, I’m sure. Ieven think about trying to act sometimes. The biggest rush I couldever have would be to be Mick Jagger at the Cotton Bowl, with80,000 fans screaming together, hanging on every strut, everymovement. . .Can you imagine that? -Skip Bayless

He is a page out of Gentleman’s Quarterly come to life. Five-foot-eleven and lean, with neatly trimmed hair and the looks of a model or a young stockbroker on Wall Street. When sizing up Skip Bayless, Mick Jagger does not come to mind.

When Bayless is not covering a live event, he works in total quiet in the living room of his Oak Lawn town house. No stereo, no chatter from the television set, no noise, please. This new era of the mini computer/typewriter allows a number of journalists to write away from the office, and Bayless works at home so often it is probably more office than home. That’s the way he likes it.

In the morning, Bayless mulls over column ideas while pedaling an exercise bike, then gathers information, usually by phone, in the afternoon. At about 5 p.m., he sits on the couch, surrounds himself with notes and press guides, places a lightweight computer on his lap, and writes for three hours.

He breaks for dinner, thinking about his wording and phrasing as he munches on a take-out order of Chinese food or a large serving of home-cooked spaghetti, then goes back for round two with that day’s column, spending a final half-hour on what he calls “my best writing.” He trims the piece to approximately 800 words, then transmits the final product to the office. He is usually through with the column by 10 p.m., but the column is not through with him. Not for a while, anyway. “I get so emotionally wrapped up when I write,” he says, “it takes me two hours to wind down. The column is always in my thoughts.”

Even his critics would agree that Skip Bayless tackles the world of sports in a completely original manner. He can be refreshing, but he can also be offensive, even shocking. A committed runner, Bayless once wrote a column that focused on his urgent need to find a secluded spot to have a bowel movement while running a marathon. “I didn’t write that for shock effect,” he says. “Every runner knows what I was writing about.” His frequent prediction columns are often so outlandish that readers could wonder whether he is serious. “I think through the situation, but 1 will not go for the obvious,” he says. “I’m just giving the reader something to throw darts at.”

Sportswriters on both papers have laughed and cried about Bayless’s columns, particularly when he inserts himself into the column. “I’m ashamed if my ego ever comes out,” he says. But it does. A prime example is the Bayless column of February 23 on the Rangers’ newest acquisition, Darrell Porter.

Porter and Bayless grew up in Oklahoma City, but on different sides of the tracks. Porter was the poor boy, the country kid who turned pro athlete. Bayless played basketball against Porter, idolized him, wanted to be him. Somewhere along the way, the reader is told more about Skip Bayless than Darrell Porter: … [Porter] could wrist-flick 20-footers as easily as I made A’s in advanced English. I made just one B in four years of high school (in driver’s ed), but I’d have traded all those report cards for Porter’s jumper, which was hotter than my Camaro SS350 and cooler than my head cheerleader girlfriend. . .That night, I held Porter to five points. . .That night was the greatest of my athletic career, I guess.

But Porter had his troubles along the way-well-publicized drug and alcohol problems among them-and Bayless also closes the column by thanking his lucky stars that he is not like the hero he had always wanted to be.

In looking back on the article, Bayless says he wept when he wrote the Porter column because he revealed himself. “I’ve received a lot of complimentary mail from people who said they had their Darrell Porters, too,” he explains. “They thanked me for letting them live out my Darrell Porter memories, and they thanked me for exposing so much of myself.”

A message, tacked on his refrigerator door, says: “Anybody who is good is different from anybody else.” Skip Bayless lives by that creed, perhaps more than even he realizes.

Very few Dallas sportswriters would call Bayless a friend. Many of them do not realize how painfully shy he is. Bayless is quiet around anyone he doesn’t know, and he doesn’t know many. He’s not the loud, obnoxious sort who irks others in face-to-face confrontations. In fact, he avoids confrontations. He is simply aloof.

“I just don’t run with the crowd,” he says.

That distance is perceived in other ways by other people. “If he weren’t so despicable I’d feel sorry for him,” says one member of the Herald staff. It is not an uncommon view among the local sports fraternity.

Envy might play at least a small role. At age thirty-four, Bayless makes roughly $110,000-$50,000 per year more than fellow columnist Frank Luksa, no fen of Bayless’s, and $70,000 per year more than the average newspaper stiff in Dallas. But, none can deny the remarkable impact Bayless made on Dallas when he arrived in November 1978.

His Morning News columns back then were crisp, usually enlightening, and always concerned the hottest sports topic of the day. While other columnists kept abreast of sports at a more leisurely pace, Bayless wrote about the same news a day ahead.

Eight years later, timeliness remains his strongest suit. But his reputation for the offbeat, even bizarre approach may overshadow his best writing. Bayless is keenly aware of taking on a persona in his columns, saying things in a way he might not in conversation.

“I’m on stage when I write,” he says. “I’m fearless. It’s like Clint Eastwood, someone who is really different in real life than in his acting roles. I don’t know if I’m the guy [pointing at himself], or if the column, my alter ego, is the real me. All I know is I can’t be Randy [Galloway] or Blackie [Sherrod] or I’d fail. How many poor man’s Blackies have there been in this city?”

There have been about as many imitation Sherrods as there have been sportswriters who drink. Sportswriters are notorious for picking up information, leads, even entire stories while enjoying a social cocktail with the right source at the right watering hole.

Not Bayless. In his teenage years, he says, his parents were too busy drinking to applaud his athletic or educational endeavors. Of his father, who died in 1974, Bayless says, “I never liked him. I have no remorse.” His mother, on the other hand, “is very strong now.” She was recently honored with a tenth birthday at Alcoholics Anonymous, which she attends every Monday night in Oklahoma City.

“I probably saw more alcohol in my first ten years in the world than a lot of sportswriters will see in a lifetime,” Bayless says. “I can remember my family giving me rum and coke or beer when I was three years old. They would sit at the table and laugh and watch me stagger around.”

His voice is steady and emotionless.

“By the time I was in high school, my father would come home and try to fight me. I’d beat his ass because he was so drunk. He was so alcoholic he would come home, sit in the living room, and tell us he was going to blow his brains out. But he was too gutless to do it, and he eventually took the most gutless way out. He drank until his liver went, literally drinking himself to death.

“Even if none of that had happened in my childhood, I don’t think I would drink. I’d still be different from others. Besides, I don’t enjoy it. I don’t like the taste. I don’t like the way it makes me feel. I’m not afraid of who I am or what I am. I like to deal with people one on one-when both of us are in our right minds.”

Bayless’s high school journalism teacher altered the course of his life. She nominated him for the prestigious Grantland Rice scholarship, which is given to one student in the nation each year and at that time amounted to a four-year, $20,000 free ride to Vanderbilt. He won it, and caught a final glimpse of Oklahoma in his rear-view mirror.

After graduating, Bayless wrote sports features for two years at The Miami Herald and three years at the Los Angeles Times. That’s where he was when the News hired him. At twenty-six, he came to Dallas for what was then a fat sum of $40,000 a year to bump heads with the Herald’s legendary Sherrod. Until the day Bayless left the News for the Herald, Dallas was a city with only two full-time sports columnists-Bayless and Sherrod.

News editors hardly flinched when Bayless informed them he was weighing an offer from the Times Herald, which he accepted in February of 1982. In just three years, some felt, he had lost his zip, or at least his credibility, with readers. They did not make a counteroffer. They told him to look both ways before crossing the street.

“Our surveys showed that while Skip clearly had a following, readers were losing interest in him,” says Jeremy Halbreich, executive vice-president of the News. “He wasn’t going to cause us to lose any circulation and, in fact, he was going to make some of our readers happy by leaving.”

Bayless will not disclose the terms of the five-year contract he signed with the Herald, but one reliable source within the paper put it at $75,000 the first year, with increases of 10 percent a year through February 1987, when the contract expires. The deal also included a car, which the Herald agreed to maintain, as well as pay for all gas and all insurance, and a free membership to the country club of Bayless’s choice (Las Colinas Sports Club).

These days, he is the consummate workaholic. He had been married in Los Angeles, but the move to Dallas eventually led to divorce. From 1980-84, he lived with a woman, but that relationship also ended because Bayless flatly refused to devote her enough time. “I’m just married to this job, no doubt about it,” he says. “I just don’t have the time or the emotions to put into a serious relationship. I’ve failed at love so many times (that] it’s the one thing in my life that eats at me. Now, I just throw myself into my work. My job comes first.”

Athletes resent it if you hammer them in print, then squirrel away when you see them. My theory is to be there, be around. Covering baseball for ten years taught me the law of the jungle. Baseball players are easily the most macho of any athletes, and more sportswriters I know fear going into a baseball clubhouse than any other. I liked covering baseball. I liked the grind. And, I liked for players to think, “Hey, this guy’s a little crazy. He’s kinda like us.”

-Randy Galloway

For fifteen years, Randy Galloway, wife Janeen, and their two daughters have lived in the same three-bedroom brick house on Denmark Street in Grand Prairie. He earns $50,000 a year more than he did when they moved in, when he feared the $240 a month payment might devour them all.

But no matter how high the tax bracket or whether he ever moves, Galloway is and will always be, as he puts it, “a Grand Prairie boy.” Stick Randy Galloway in a Manhattan high-rise, pull him out ten years later, and he would still be a Grand Prairie boy. There is a difference, though. Some Grand Prairie boys still hang out at the County Line and do not accept change in their lives. Galloway accepts change and, above all else, adjusts to it.

On a brisk March afternoon, Galloway is wandering around the swimming pool that dominates his back yard. The pool, and a large den added onto the back of the house last summer, are the only changes in the original structure. He is walking and, as is his nature, he is talking. Few people ever catch Galloway glum. He seems forever chipper, forever young.

“When I covered baseball,” he says, “people were always asking me what I was going to do when I grew up. Well, I never plan to grow up. I knew I was good at baseball, and when the column opportunity came up, I wasn’t sure how good I’d be covering a wide variety of sports. Now, I consider the column the greatest thing to happen to me.” He pauses, then adds, “What I’d really love to do is own a few racehorses, follow the track. Otherwise, I could write this column forever.”

A member of Grand Prairie High’s class of ’61, Galloway married his childhood sweetheart, attended Sam Houston State University for two years on a $250-a-year journalism scholarship, followed “some of my hoodlum friends” to North Texas State, flunked out, and went to work for a construction crew.

In his early twenties, Galloway worked construction full time and wrote part time for the News. Former News sports editor Walter Robertson saw the potential and convinced him to accept a full-time job at the Port Arthur News. Galloway worked there fourteen months before Robertson called him back. (“I hated to leave Port Arthur. I was making $105 a week, and I liked all those Cajuns down there. I liked their food, and I liked their act.”)

From 1972-1981, while his daughters were growing up, Galloway was often on the road, covering the Texas Rangers. The grueling pace kept him away from home a total of five months each year. He still travels considerably, but not as much as he did on the baseball beat. Daughter Gina, eighteen, was the president of the student body at Grand Prairie High School and is a member of the National Honor Society. Jennifer, thirteen, is in the seventh grade.

Galloway’s paycheck these days amounts to $70,000 a year. That doesn’t include what he picks up from occasional magazine pieces, or the money he makes off a weekly WRAP radio talk show. It all works out to some $80,000 a year.

He has never claimed to be a high-caliber writer, though he probably belittles himself too much. “I don’t believe my writing is ever going to totally carry a column because writing is not my strength,” he says. “My strength is I’m never afraid to give an opinion.”

That’s a fact. In print, on the air, in a bar, or in his own living room, Galloway will give an opinion, either vocally or with a pen some consider filled with poison. But he can also be very engaging, very charming. He is not just a character, but a leading character, in most surroundings. Everyone knows, or thinks they know, Randy Galloway, and everyone seems to have at least one story about him. He is as outgoing with a clubhouse boy as he is with a major league manager, if not more so.

But when Galloway is at his best as a columnist, he is tough. Nobody goes for the jugular any better or harder. Even when he’s at his worst, he usually writes tough. “I’m considered the News’s DH- the designated hammer-and I’m totally aware of that. The reason I can write that way so often is because David and Blackie are so good with the humor approach.

“The three of us write a total of twelve sports columns a week, and I would hate to think there would be twelve Randy Galloway columns. Readers would get sick of being hit over the head every day. But with David and Blackie supplying the lighter touch, I can go to my strength.”

He does force a few. On some days, his columns begin with a boom but fade quickly because he has said it all in the first few paragraphs. He spends the rest of those columns supporting an early thought, but sometimes he spins his wheels in the middle and burns out near the end. The hammer falls so swiftly, so surely, in those early paragraphs, that it is almost impossible to maintain that impact throughout the column. Every now and then, the reader needs a rest, but you won’t rest early with Galloway. As an example of his candidness and style, here are the opening lines of a January column on the Dallas Cowboys’ quarterback situation.

As you know, Gary Hogeboom has asked the Cowboys to move him out of town, out of sight, out of mind.

Smart move for Gary. Smart move for Dallas.

Now how about Danny White?

Hopefully, he’ll take a read off Hogeboom’s request and also ask to be traded. Like today.

If Boomer’s gone, why should White do such a thing? For the good of the team, that’s why.

Exactly what the Cowboys of ’86 don’t need is a 34-year-old White hanging around, playing every minute, every quarter, every game. And if he’s here, you know that’s exactly the way Tom Lan-dry will use him.

When Galloway referred to Eddie Chiles in print as the “Elmer Fudd” owner of the Rangers, Mrs. Fran Chiles sent him a Bible with several scriptures already marked. Hate mail? To Galloway, it is love mail. Somebody out there is reading.

“Danny White has a legion of fans, many of whom are women and most of whom write me,” he says with a grin. “Your desk will fill up with hate mail in a hurry when you knock Danny White. I’ve also probably been sentenced to hell more times than anyone in the Dallas area for blaming the Baptists for keeping horse racing out of Texas.

“I’m just a sports fan that happens to be a sportswriter. Sports fans love to give their opinions. The only difference between me and millions of other sports fans is I’m able to walk into a clubhouse or pick up a phone and back up or back off my beliefs by talking to the right people.”

Oddly enough, though others easily warm to him. Galloway cannot or will not write an in-depth profile. He does not concern himself with the athlete as a person. He talks ball. Hard ball.

“I do not sit down and try to find out how a guy really is,” he says. “I write four times a week, and I want to use that space to deal with the hottest sports topics of the day. I’m not a guy who explores with this column. The key to this business is just like the teams we cover-you’ve got to play to your strengths and stay within yourself. My strength is reporting the news as I see it.”

Not only does Galloway stay away from in-depth personality interviews, he does not let many people get in-depth with him. In some ways, his loudness is a cover for his own privacy, perhaps even for his own particular shyness. Others see the flamboyance on the outside and think they know the man on the inside. In his own way, Galloway is as private as Bayless, except that Galloway shields himself behind a loud exterior.

If he’s not putting in his twenty-five miles a week of running (“just to keep a beer gut down”), if he’s not covering an event or making a quick stop by a Dallas or Arlington hangout, if he’s not living out of some hotel room, Randy Galloway is usually at home in Grand Prairie, Texas.

That’s where the good ol’ boys live.

I read the papers, but I don’t read them cover to cover. I’d rather have-dental surgery than read box scores and agate type. . .I keep thinking about the Texas-OU locker room. I’ve covered most of them for the last twenty years, and I don’t think I want to be down there asking them what they did on third and long when I’m sixty-five. But I do love writing, and I do have a family to feed, so who knows ? You’ve got to take the writing seriously, even if the subject matter is not.

-David Casstevens

A good column is guaranteed to cost David Casstevens two dollars in Cokes, chips, and candy bars. When you get paid $70,000 a year, you can afford a few Snickers, but he agonized this way in his first newspaper jobs, a nine-month stint in 1969 at the Abilene Reporter-News and a three-year stop at the Waco Tribune Herald.

He writes a while, then Fidgets a while. He writes a while longer, and he runs his hands through his hair until strands point this way and that. Kevin O’Keeffe of the San Antonio Express-News says Casstevens on deadline looks like a wild scientist gone amok.

“Everybody sweats his work,” Galloway says, “but David sweats more than anybody I’ve ever seen.”

He gets up, sits down, gets up, goes to the vending machine for a Coke. Goes back, writes a while. . .looks down. . .and he’s completed all of three paragraphs.

“What hurts,” Casstevens says, “is when you’re in a coffee shop and you notice that the guy with the newspaper next to you has read your column in about twelve seconds. You’ve spent all that time trying to turn a phrase, but for some readers it’s just something to do between cups of coffee. That’s what I mean about not taking what you do seriously. If you did, you’d go crazy.”

Sports information directors around the Southwest Conference will tell you that Casstevens cares much more than he lets on. He is always among the last to leave their press boxes on football Saturdays. Sometimes, Casstevens and the cleanup crew sweeping nearby are the only ones left. Often, the janitors must wait for him to leave so they can turn off the lights and lock up.

Yes, Casstevens does care. He does agonize, not over sports but over his writing. And it pays off for him. His anecdotes are highly entertaining, his subject matter is light fun, and he knows how to take a reader through it all. He covers the offbeat-the bats living inside the University of Texas football stadium, a pro basketball player who spends the All-Star break a( a haunted house in Louisiana, old and crippled basketball trainers with gripping stories. Last year, he won the Dallas Press Club’s Katie Award for best sports column writing. For a sample of Casstevens’s style, here’s his introduction to Texas basketball history, aimed at visitors coming to Dallas for the NCAA Final Four tournament:

. . .If you know anything about Texas history, you remember the heroic story of William B. Travis. Realizing there was no longer any hope for the [Alamo], Travis drew a line in the dirt with his sword. He then asked those who wished to remain with him and defend the Alamo, to the death, if need be, to step across the line.

Well, they all joined Travis, including Bowie, who demanded his hospital cot be moved across the fatal side of the line. One fellow, Milo Smidlap, a drummer from Philadelphia, had second thoughts. Only Milo took a sneaky reverse step back across the line, a prudent but cowardly act for which he was roundly booed. This event was the first recorded incidence of a maneuver we know today as a backcourt violation.

But he is not always appreciated by the hard-line, new breed of sportswriters whose idea of a great column is one with nerve and insight. Some writers and readers consider Casstevens too soft, but at a time when the pendulum has swung so far toward the blunt and gutsy columns, the Casstevens touch has become the unusual one. If not Sherrod, Casstevens is the Dallas columnist most likely to bring out the human emotions of sports, and that is no small feat. It takes writing skill.

Bayless is a frustrated jock who happens to write sports. Galloway is an avid fan who happens to write sports. Both are sports addicts. Not Casstevens. He is a writer who happens to write sports. “I’ve never sat around and talked ball for hours,” he says. “I can’t even remember the scores of bowl games I covered just two or three years ago. They all run together. I don’t have many lasting sports memories.”

Casstevens is forty now and the gray is gradually winning the battle of the hair. He is gracious, mild-mannered, clever without being brash, a great observer, and a great listener. His approach to the world of sports may not sit well with the jockaholics, the superfans. He happily leaves the hammering to Galloway. But his style is appealing to the casual sports fan, of whom there are great numbers, and to anyone, fan or not, who likes to read a good story.

When Dave Smith replaced Walter Robertson as executive sports editor in 1981, he said he wanted his section to be like a television set. If the reader is not interested in one story, he should be able to turn to another channel, so to speak. The trick is to have so many different channels that a few are appealing to everyone.

“I think people perceive sports columnists as experts,” Casstevens says. “That’s where I miss with some people. They take this stuff very, very seriously. I think in their minds I don’t have the proper reverence for sports.” He refuses to go on radio sports talk shows, which frequently ask top-name writers to appear. “I’m not comfortable explaining why the Cowboys moved someone from left tackle to right guard. Also, I don’t care about selling myself or my name to be real high-profile. I’d like to be able to be glib and express an opinion on anything, but it’s not my style.”

Fort Worth, his home town, suits Casstevens’s style. He lives there today. Casstevens attended Poschal High School, which produced such unorthodox sports figures as the free-spirited ex-pro footballer Don Looney and Semi-Tough author Dan Jenkins. He graduated from the University of Texas, moved through Abilene and Waco, then worked for nine months at the Herald in 1971.

Casstevens left the Herald to cover pro football’s Oilers for the Houston Post. By then, he was making $220 a week. He spent eight years in Houston, including the last five as a columnist, before moving back into the Dallas arena for the News in 1980 as a feature writer. When Bayless departed for the Herald in 1982, Smith named Casstevens and Galloway as co-columnists and began both at about $50,000 a year. Now living back in Fort Worth, Casstevens has come full circle.

“When I was growing up here, I never thought about writing,” Casstevens says, “I read Jim Trinkle’s column in the Star-Telegram, but I never got real conscious of sports columnists until my freshman year at North Texas. That’s when I first started reading Blackie’s stuff.

“I’m probably too thin-skinned to be a columnist,” Casstevens says. “Randy loves the nasty mail. The more violent the nature of the letter, the more pleasure he gels from arousing that emotion. I’m not that way.”

His way is much more relaxed. He lives not too far from the Fort Worth zoo (“I swear, it sounds like a jungle some nights”) with Sharon, a legal secretary, and their daughters, five-year-old Amy and three-year-old Anne. “It’s not like Dallas is a New York City, but I’ve been in all that traffic and I wanted to live in a more peaceful place,” he says. “This is a family-oriented period in my life. I got a late start on being a father, and I enjoy it. This is starting to sound like ’Father Knows Best.’ It’s not quite like that. . . .”

As for the future?

“I worry about where do I go from here,” he says. “I don’t want to go downhill and coast, but I don’t have any burning desire to write a book, either. In the pecking order of sports writing, this is the top of the line, unless you’re the sports editor. The toughest thing is just to maintain enthusiasm. When I get to be Blackie’s age, I can’t imagine covering sports as well as he does. There’s a sameness to it all. Even when the players change and the times change, you’re still writing basically the same thing. It’s like the Texas-OU game. You go into the locker room, and all the faces are different but the people are the same age as they were the year before. You’re the one who’s a year older. And pretty soon, you realize that in the overall scheme of things, it’s really insignificant what we do.”

Unfortunately, I’m afflicted with making the attempt of hitting a home run every column. I want the worst it gets to be an eight on a grade of ten, but it simply doesn’t work that way. Sometimes your material is lacking. Sometimes your idea is badly conceived. And sometimes you ’re having a bad day.

-Frank Luksa

Sports columnists, like everyone else, can have a bad day in two ways-something can be bugging them in their private lives, or something can be bugging them in their careers. The idea is to not let one bleed over into the other. That’s the idea, anyway. But when the heart is suffering, one does not suddenly brighten by sitting in front of a typewriter.

Frank Luksa is having lunch in Dallas’s West End district, a short walk from the Times Herald building downtown. He glances out the large plate glass window where he is eating lunch and notices that a chimpanzee, carrying a ghetto blaster, is walking out of a nice restaurant across the street.

“There I am, late at night, leaving a bar,” Luksa says in a dry drawl.

As Luksa speaks, Bob Galt, longtime friend and co-worker at the Herald, is in a hospital across town, dying of cancer at age fifty-four. Not only is Luksa faced with the inevitable death of a buddy, he is also faced with having to write about it. He knows that someday, in some column that will take maybe three hours to write, he will bring Galt back to life, recalling the happy days and offering the happy praise. And he will find a way to keep his spirits up and press on.

Luksa has had to press on before. His wife of twenty years, Henrietta, once beat uterine cancer. On another occasion, their third child died three days after birth, and Henrietta almost followed.

Then came Luksa’s heart attack in 1983 at age forty-eight.

While double-faulting tennis serves, he felt an odd twinge; then all of the classic symptoms of a heart attack took over, except for pain. Nausea, sweating, dizziness, tightness in the chest.

“The doctors wired me up like a stereo,” he says. “I had everything but weights and pulleys on me. Sure enough, I’d had a heart attack and was in the hospital for twelve days. I can remember the exact date it happened-April 15, income tax deadline. I assure you, there was no correlation.”

He finishes off a bowl of red beans and adds, “Look, everybody has problems. I don’t want to sound like I’m crying. I don’t care much for people who tell a lot of poor-me stories.”

But the heart attack and other personal problems have given Luksa a much softer view of sports. How can he write about a sporting event as if it were a life and death struggle when he has faced real life and death matters?

“That’s why I don’t preach in my column,” he says. “Some of the ’major’ issues in sports seem kind of trivial to me. Sports never was life and death to me anyway. In some odd way, maybe the heart attack has been a benefit because it’s made me have a different perspective on people, my job, and the events I cover.”

Luksa’s columns are fireside, poolside, barside chats. He does not often grip or stun the reader by immediately biting someone’s head off. One of his best columns (Feb. 3, 1985) was one of his longest-a piece on Muhammad Ali’s sad physical and mental state after years of being banged around in the boxing ring. Luksa does not ridicule Ali, who now talks in a slur; he allows Ali’s own comments to do that, But it is not for the sake of a put-down; it’s to show empathy for a fallen hero.

For an instant, and almost the only instant, the saucy Ali of yesteryear reappeared. Quickly he replied (to a middle-aged man in the audience): “You’re not as dumb as you look.”

Everyone laughed. People always do at first encounter with Ali. After hearing him for a few minutes, the laughs become nervous. Afterward, if there are chuckles, they are awkward and forced.

To read Galloway, be prepared for a quick bolt of lightning. To read Luksa, be patient. Stay with him and see where he leads. His style is better suited for an educated audience, not an “everyman” audience. He prefers to weave a story in a style that is not always appreciated by the die-hard sports fen.

His wit is very dry, “sometimes to the point of dust,” he says. In an excerpt from a July 2,1985, column, instead of writing “I’m getting sick and tired of the cheating going on in college athletics ” Luksa employs a style that is his alone:

First day back from vacation and I find myself, like the mythical and malodorous troll, clambering from beneath a bridge to fume. The shame of it is that someone so lithe and tan, so laid back from weeks of indolence, should return to work with bile in his craw.

Luksa grew up in Georgetown, Texas, just up Interstate 35 from Austin. Recalling his days as a high school quarterback, he says, “I was, and still am in my memory, one of the all-time greats for the Georgetown Eagles. Unfortunately, scouting was in its primitive form so I was denied a scholarship.”

Luksa attended the University of Texas for four years. “It’s possible I flunked out,” he says. “My father was the head of the sociology department at Southwestern University, and his patience was exhausted. He said it was time for me to try working.”

For sixty-five dollars a week in 1957, Luksa took a job in East Texas with the Gladewater Daily Mirror, then moved quickly to the Tyler Morning Telegraph for a ten-dollar-a-week raise.

After service in Korea, Luksa earned a journalism degree at UT, and went to work at the Fort Worth Star-Telegram in 1960, covering the Dallas Cowboys. Fort Worth loves the Cowboys too, but the Cowboys beat man at the Star-Telegram has always played second fiddle to the Dallas writers. Luksa produced clean, entertaining copy that went largely unnoticed in Dallas for more than a decade.

In 1972, the Herald brought him to Dallas, for just over $200 a week, to cover the Cowboys, He wrote almost exclusively on the Cowboys until 1980, and he is still linked to pro football more than any other sport. When the Texas Rangers opened the 1985 season, Luksa wrote a column on the Cowboys. On college football’s signing day this year, Luksa wrote a column on the Cowboys.

“The bottom line is you cannot overwrite the Cowboys in this town,” he says. “They simply dominate the market.”

In 1980, Luksa benefited when the Herald made a few changes. Filling in on the days Sherrod was off, he began writing three columns a week and Cowboys game stories. That lasted until Bayless arrived in 1982. Bayless came over on Luksa’s forty-seventh birthday, and Luksa soon was a very bitter odd man out.

“I don’t like to complain about it,” he says. “Let’s just say I stopped speaking to a number of people in management. But, I knew something had to happen with the way the paper was being run, and 1 decided I’d take my chances with the next editor.”

Luksa swallowed his pride and waited. He was right. When Sherrod kissed the Herald goodbye in 1985, Luksa stepped in. His subtle approach, like any softer viewpoint these days, does not always win him the respect of the tough guys in the business. But as he goes through this second year of full-time column writing, he is gaining in stature.

“I don’t want to say he’s not appreciated, because he is,” says Sherrod. “I don’t want to say he’s underrated, because he’s rated. But Frank has been an awfully, awfully good writer for a long time. He has always had that real good touch. A lot more people around the country are becoming aware of how excellent a writer he is now that he’s doing the column.”

Luksa and Bayless may be the Heralds one-two punch, but they are far from close. For personal reasons, Luksa has not spoken a word to Bayless in five years.

In 1981, Luksa found former Cowboy Thomas “Hollywood” Henderson in a drug clinic and wrote about it. The next day Bayless, who was still at the News, went on a radio show and dubbed the whole thing a hoax. A friend of Henderson’s heard the program, and soon an irate Hollywood was phoning Bayless.

To prove that he was serious, Henderson asked Luksa to come to the phone and tell Bayless that he had indeed entered the clinic. Luksa did so, after Bayless promised that Luksa would not be part of the story. Bayless not only quoted Luksa in the News the next day, he portrayed him as a dupe who had been tricked by Henderson. Luksa has held a grudge ever since. He even went so far as to request that Cowboy publicists and others in the National Football League seat him anywhere in the press box as long as it was not next to Bayless.

Of his approach to sports, Luksa says, “It certainly diminishes the appeal of commentary if you’re ripping and slashing every day. The business seems to be going toward tougher writing, but I don’t think you have to impale the people you are writing about. I have an affinity for people in the arena. I think I’m sympathetic to how hard they try and how difficult their jobs are. I’ve seen too many knee-jerk opinion pieces where the columnist ends up looking foolish. I would rather be respected for being honest. I can live with that.”

He has learned to live with what life deals out, the highs and the lows, and he has seen his share of both. This past Easter Sunday, when other columnists were preparing pieces on the Final Four championship matchup at Reunion Arena the next day, Frank Luksa received the phone call he knew would come sooner or later. Bob Galt was dead.

The others wrote basketball that day. Luksa wrote: … It would offend his gentle nature to know that anything he did-even dying-upset anyone. Sorry, Bob, but we’re going to have our cry anyway. You’ve only yourself to blame. It’s your fault. We weep because of the way you were.

I sure hate to see sports get out of the entertainment business.Seems like there’s so much seriousness, it defeats the reason forsports. My generation of writers-and the people we idolizedand studied-came along right after World War II. There hadbeen so much seriousness, the country was so grim, everyone justwanted to have fun when the war was over. We were the productsof an era that was seeking laughs and entertainment. That’s theway we tried to write it. -Blackie Sherrod

He has a genius reminiscent of Johnny Carson. In their respective fields, they are masters of phrasing and timing. Neither is inclined to ask unsettling questions in an interview. Both are more likely to rely on cleverness and their own peculiar insight into seemingly one-dimensional subjects. “He could write about a cow jumping over the moon, and the majority of his readers wouldn’t care,” Bayless says of Sherrod. “They’re reading Blackie for his brilliance. They’re reading him for his words.”

Sherrod’s words can carry a bad interview, and his words have amazing grace over the long haul. However, with each passing year, newcomers to the journalism profession think Sherrod, at age sixty-six, is coasting. One out-of-state columnist says, “I thought he would light a fire under himself when he moved to the Morning News. Instead, he’s over there writing his memoirs.”

“I’m glad Blackie left,” says Dave Eden, who was the Herald’s features editor when Sherrod was finishing up there in 1984. “His departure opened up a column spot for Frank, whom I prefer reading. Blackie is an institution and did a lot for journalism in this state and in this country, but his time has passed.” Eden believes that Sherrod has an idiosyncratic, old-school style that limits his readership: “We received maybe ten phone calls from people saying they were dropping the paper. Ten years ago Blackie might have taken a very large audience, but not today.”

To be sure, Dallas is a changing city. The newcomers, both readers and writers, have not been raised on Sherrod’s style. They prefer timely, meaty stories on fresh subjects. On the other hand, there is a segment of Dallas society that would rather read Sherrod than any writer, in or out of the newspaper business.

“The great thing about Blackie is that he just never writes a bad column,” says Steve Perkins, editor of the Dallas Cowboys Weekly and a longtime Dallas newspaper man. “Blackie never sloughs off. There arc times when he thinks he is sloughing off, but those are gems, too.”

Denne Freeman, Texas sports editor for The Associated Press, says, “Some younger journalists feel they have to put aside the ’dinosaurs’ in the business. But hey, the Morning News did not hire him away and pay him big bucks without doing a helluva lot of research and studies. The Times Herald people can say what they want, but everywhere I go Blackie is still the most respected guy in the press box. And he’s still the most literary, knowledgeable sportswriter I’ve ever been around.”

“I hate to use the word because I think it sounds fancy, but I think I’m more of an essayist than an editorialist,” Sherrod says in his gravelly voice. “You do what you’re most comfortable with, and I would not be as comfortable as a slasher. I’m not critical of the new breed. I just wish for their own sake, for their own enjoyment, they’d get a bigger kick out of their jobs. The survivors, the guys who have been around a long time, almost without exception have a great sense of humor as a part of their personal makeup.”

Sherrod does not always display that sense of humor to younger journalists. Some consider him stuck up, standoffish. He does not endear himself to many strangers, in or out of the profession.

“Sometimes it’s an age difference,” he says, “but the newspaper business is a cold, hard business now. It used to be almost like a family, warm and caring. A whole lot of people you meet now are just en route someplace. After a while, if you start to see that, you let them go and take care of yourself.”

He is sitting on a couch in a large living room, yelling at his cocker spaniel to climb down off the guest (“He’s a bed-wetter,” Sherrod says, “my bed”). He lives in North Dallas off Royal Lane with Joyce, his wife of five years (a previous marriage lasted twenty-four years; Sherrod has no children).

The living room also serves as a library, one of several rooms with rows of books by James Thurber, Damon Runyon, Ring Lard-ner, S.J. Perelman. His long, narrow office, which looks out onto a large swimming pool in the back yard, is also filled to the brim with books, notebooks, radio equipment for his KVIL sports commentary, and pictures of friends in and out of the sports world.

Sherrod was born on a farm outside Bel-ton, Texas, and, at 140 pounds, lettered three years in football, basketball, and track. After a year at Baylor on a scholastic scholarship, he tried to play wingback for Howard Payne College in Brownwood during the Great Depression.

When a hip injury caused his scholarship to be taken away (standard procedure then), Sherrod earned his scholarship playing trumpet in the school band. He later fronted a seven-piece Dixieland band two nights a week, then played guitar while fronting a nine-piece swing band. He worked construction a while, then took a job at fifteen dollars a week as the Temple Telegram’s Belton correspondent. On December 8, 1942, he joined the Navy.

During a two-year period, Sherrod was a tail gunner on a torpedo plane based on the U.S.S. Saratoga in the South Pacific. Lately, he has been questioned by those unaccustomed to his habit of referring to the Dallas Cowboys as “Your Heroes.” He is, of course, joking. “My heroes are not athletes,” he says. “My heroes are guys that can put a torpedo plane on a carrier at night.”

After the war and short stints writing news in Temple and at radio station KFJZ in Fort Worth, Sherrod was hired at the Fort Wbrth Press. He became sports editor of the now-defunct Press in 1949 and put together a legendary staff-Dan Jenkins, Bud Shrake, Julian Read, Jerre Todd, Andy Anderson, and, of course, Sherrod. “When people talk about the great teams of all time, they talk about the 1927 Yankees,” Galloway says. “Well, give me the ’57 Fort Worth Press.”

Sherrod moved to the Herald in 1958. For $185 a week, he wrote six columns every seven days and served as sports editor. “I’d go into the office at 7 a.m., and I’d have two hours to write my column and play sports editor, too,” he says. That was when the Herald was strictly an afternoon paper. Sherrod remained in charge of sports until 1976, when holding down both jobs became overwhelming.

The News had tried to hire him the first time in 1978, but the Herald countered with a seven-year contract that was good until Sherrod’s sixty-fifth birthday. It was the first $100,000 contract signed by a Dallas newspaper writer.

But Herald management continued to change and prod him as it did the other old-school journalists. Though Sherrod would not admit to any hard feelings (“I just withdrew,” he says), he finally grew weary and accepted the News’s next offer in 1984. The Herald refused to let him out of his contract, making him a lame duck columnist there in 1984.

A Times Herald staffer says he has it on good authority that Sherrod signed a five-year contract with the News at $250,000 a year, an astonishing figure by newspaper standards anywhere in the country. The contract runs until Blackie is seventy.

“I’ll write until I die,” he says. “I have no desire to retire. If they get tired of me, I’ll try to write a book. I’ve started several.”

Sherrod makes his own schedule and usually answers to no one. Every writer weeps when a masterpiece is cut or badly edited. But it’s a good bet that what you read from Sherrod is almost exactly the way it was when the column came spitting out of his computer.

There was one near run-in with Dave Smith. Following the tragic explosion of the space shuttle Challenger, Sherrod used a quote from veteran test pilot Chuck Yeager as a tie-in to a column on Chicago Bears lineman Dan Hampton. “Yeager had merely pointed out that risk is a part of the job, and I was making that same comparison to Hampton’s job,” Sherrod says. “In my judgment, it was a valid quote.”

Smith saw otherwise. He thought the comparison was in poor taste and asked Sherrod to rewrite the lead. “I don’t rewrite,” Sherrod answered. Smith was left to pull the column completely, so the News hit the streets without Sherrod that day.

“As far as I’m concerned, a columnist develops his own personality in print and I don’t feel you can tell a columnist what to write,” Smith says. “If I think what they write is in poor judgment, I respect their right to leave it as it is, but I also reserve the right to pull it.” Of course, Smith is well aware that Sher-rod’s legions of readers love his unique style (“We hired him to be Blackie”), so most “Sherrodisms” escape the editor’s pen. That includes the Archie Bunkerish tone of Sherrod’s “our neighbor Jones” quips in his Sunday notes columns, “Scattershooting while wondering whatever happened to. . . .” Feminists who read Sherrod might bristle at lines like “Our neighbor Jones sez a childish game is anything your missus beats you at” but such unreconstructed chauvinism is part of the Sherrod manner, as are his frequent references to himself as an old-timer (“us old grassrooters,” “this old rooster,” etc.), and his feigned ignorance while explaining something technical (“If you seek scientific details of the ’46 Defense’ then you must apply elsewhere. A football scholar tried to explain it to me and sprained his tongue. . .”)

It is sad, and somehow unfair, that Sherrod would now be criticized by others who could not match his wit and prose in their wildest dreams. Sherrod ranks among the great sportswriters of all time, and he will be remembered that way long after the current crop of writers has retired. If they stay around long enough, Bayless and Galloway and Casstevens and Luksa will know how Sherrod feels. Someday, their styles will be challenged by a younger generation of reporters with an entirely different perspective on sports and sports writing. “Everything changes,” Sherrod says with a shrug.

In closing, witness the brilliance in Sher-rod’s March 26 column concerning sports’ greatest thrills. Notice the vivid, living images:

Another vote [for favorite sports moment] favors the Kentucky Derby post parade, when the gleaming colts prance out of the paddock chute onto Churchill Downs dirt, stepping daintily, bobbing their long noble necks as the band strikes up My Old Kentucky Home and 125,000 sentimentalists, overcome with julep encouragement, try to hit the high notes.

Others believe the most dramatic moment is when the announcer bawls, “Gentlemen ... start your engines!” at the Indianapolis Speedway and immediately 33 furious whines cough and begin their throaty screams that will take over your eardrums far the next three hours.

True, everything changes, though ourmemories of great sporting events andsuperb athletes are preserved for a whilethrough the work of writers like Sherrod. Heand Dallas’s other sports columnists canmake readers care because they care. Theyapproach their task like the legendary RedSmith of The New York Times. Smith, askedhow he came up with his ideas, said thatwriting a column was really not that hard.Whenever it came time to write, he just satdown at the typewriter, opened a vein, andbled awhile.

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Local News

In a Friday Shakeup, 97.1 The Freak Changes Formats and Fires Radio Legend Mike Rhyner

Two reports indicate the demise of The Freak and it's free-flow talk format, and one of its most legendary voices confirmed he had been fired Friday.

Local News

Habitat For Humanity’s New CEO Is a Big Reason Why the Bond Included Housing Dollars

Ashley Brundage is leaving her longtime post at United Way to try and build more houses in more places. Let's hear how she's thinking about her new job.

By Matt Goodman

Sports News

Greg Bibb Pulls Back the Curtain on Dallas Wings Relocation From Arlington to Dallas

The Wings are set to receive $19 million in incentives over the next 15 years; additionally, Bibb expects the team to earn at least $1.5 million in additional ticket revenue per season thanks to the relocation.

By Ben Swanger