THE ANTEROOM of the office suite on Central Expressway in Richardson is crowded with smiling young people at all hours of the day and evening. Cheerful, polite teen-agers sit and visit, often accompanied by younger brothers and sisters. Sometimes, as many as three young fathers are riding herd on their toddlers simultaneously, supervising the interactions of the 2-year-olds and trying to prevent them from uprooting the potted plants. No one walking through the door of the New Place Program Inc. would ever suspect that its clients are there to disentangle themselves from dependencies on drugs and alcohol.

Prominently displayed on the walls are celebrity photographs. In one of them, former Gov. Bill Clements and Roger Staubach flank a curly haired man whose arm is extended to shake hands with Nancy Reagan. In another, a man with a mustache is warmly embraced by Carol Burnett.

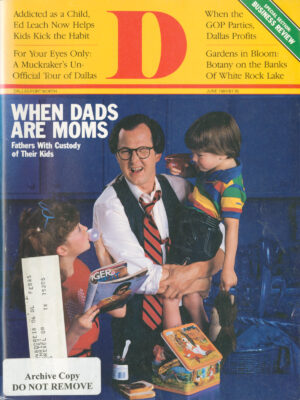

The man pictured in the Nancy Reagan photograph emerges from an office to embrace each of the members of the waiting crowd before ushering them into a meeting room. His name is Ed Leach, and he is the president of New Place Program (NPP). He no longer looks as hip as he appeared in the photograph; now he wears a dapper, dark suit that seems to emphasize the slightness of his build, and his hair is clipped close. Leach, 39, radiates nervous energy, and his face is that of a survivor.

In the meeting room, Leach is joined by the man in the Carol Burnett photograph: Archer Simms, the NPP director of counseling. They are leading a support group filled with people who have been off drugs or alcohol for a short time-in some cases as short as two days. A group of teen-agers from a Richardson high school fill one side of the room. Five of them, two boys and three girls, are sprawled on oversized pillows on the floor, shoulders touching or arms around one another in a gesture of mutual support. They were recruited into the New Place program by Rob, who is sitting next to them. “When I got straight, I knew I was either going to have to give up my friends or help them get straight, too,” Rob explained earlier. He told them about the program, and they signed up, expressing relief to be free of pills, pot and booze. “I don’t know why I was doing it,” one of the girls says now in the support session. “I certainly wasn’t enjoying it.”

Rob, a lanky 16-year-old with braces on his teeth, is a student at Berkner High School in Richardson. He came to New Place Program directly from a Grayson County jail, where he had landed for filching a battery with some friends during the big cold spell before Christmas. At that point, he had already been away from home for a week because his mother had given him an ultimatum: either stop smoking marijuana or get out.

Rob’s mother and lather, Sue and Carl, are not typical parents of clients in a drug-abuse program, since they both work in the healthcare field. They were involved in “Tough Love,” a support group for parents of adolescents with problems, and a woman working in that program told them about Ed Leach. Sue and Carl had little choice; no other outpatient drug-abuse treatment program existed.

Rob was skeptical, even angry, when he first encountered the New Place Program. He told Sue that he hadn’t seen so much hugging since the time he had worked at a pizza place where most of the employees were self-proclaimed bisexuals. Carl and Sue admit that they had doubts, too. “I didn’t know whether to trust these people or not,” says Carl. “The things they said about motivation and the like made sense to me from my experience as a manager, but when you are giving them your own kid to work on, it’s different. But our initial contact was positive. There was a sense of closeness and trying to communicate.”

New Place Program is built on a technique that, according to Leach and his partner, John Tartaro, is designed to “accelerate the processes of change in people’s lives.” Carl says he might not have accepted the idea “had Rob not shown such a quick, dramatic turnaround. The change-Rob now seems to like us both, and he communicates with us-was almost immediate. It was like somebody had cut his chains off and freed him. Rob had been in counseling a year and a half, and they had never been able to touch the substance-abuse problem.”

One reason that Leach’s program is so effective is that he has been through it all himself. The details of Leach’s life are harrowing, but he’s not afraid to share them with those who are going through the same kinds of hell.

He first became dependent on drugs and alcohol before he could talk. During his youth, he lived all over Latin America, where his American father was working as a mining engineer. When he was about 1, his family was living in Ecuador, where he developed some allergies. “My parents took me to the Gorgas Clinic in Panama. The doctor said I was allergic to milk and told my parents that they should open two six-packs of beer a day and pour them down me. So between the ages of 1 and 4, I had a habit of eight to 12 bottles of beer a day. When I was 4, our doctor told my mother to take me off beer because I was getting too fat. She tells me I cried a lot; I was obviously going through withdrawal.” The doctor then told her to give Ed phenobarbital to stop his crying, which caused a second early dependence.

Leach started imbibing alcohol regularly again when he was 12. After his parents’ parties, he would drink the alcohol that the guests had left behind. At 13, he left his parents’ home in Mexico City to attend a Catholic minor seminary in San Antonio, where he began studying to become a priest. But Leach, a rebel by nature, would sneak the sacramental wine after Mass. One summer, a friend invited him to drink whiskey with him. “I drank it like water; I got nasty, stinking, puking drunk. I realized then that that was the state I liked more than anything in the world.”

At 15, Leach was thrown out of the seminary. The priest in charge told him, “Eddie, many are called, but few are chosen. You are called, but you haven’t been chosen.” So Leach returned to Mexico for schooling. On the surface, he was a successful kid (he was elected the president of his class as well as the funniest and most popular). But alcohol was still a big part of his life, and he says that inside, “I felt so alone and wretched.” His parents became concerned about his behavior and sent him to a military school in Kansas.

After initial misery because of his lack of a perfect command of English and a rather brutal hazing, Leach became a success at the military school, too. “But that didn’t keep me from living a kind of double life. I used to love to go down to skid row to drink with the bums. I invariably got caught drunk and was punished, but it didn’t have any effect on my behavior. When I turned 18, I spent a lot of time in bars drinking beer. Don’t ever let anybody tell you that the problem of kids drinking in high school is new. It has always been there, though maybe not with the intensity that exists at present. When I graduated from high school, I was a full-blown alcoholic.”

Leach attended the University of New Mexico for a short time, then transferred to the University of the Americas in Mexico City, where, he says, the years between 1963 to 1966 “were a nightmare. Not only was the alcohol lowering my self-esteem, but this was when I first really got involved with drugs. I wanted to study for my first exam with this gorgeous blonde. Have you ever heard of Benzedrine? I took two, gave her one, then took two more. When I took those pills, I went from a very insecure, terrified college student to a brilliant and self-assured Einstein in about 30 minutes. I got smart. I hadn’t studied during the whole quarter but I studied on those pills and made 100 on the test. I thought, ’Hot damn, this is the best stuff since night baseball and ice cream.’”

For a year and a half, Leach didn’t go a day without swallowing 50 “white crosses” (10-milligram amphetamines). He couldn’t get out of bed without taking at least 15. He was 5-foot-10 and weighed between 95 and 98 pounds. He began exhibiting signs of paranoia, tiptoeing around his block at noon in broad daylight and indulging in senseless mile-a-minute conversations. His family took him to the finest psychiatrist in Mexico. “I would do 100 milligrams before going into the office so that I would be up for the consultation. The shrink’s advice was that I needed a Mexican girlfriend. He didn’t bother to ask me about drugs. In fact, he prescribed a few more. And by that time, I had already started taking downers to counteract the effects of the uppers. Plus the alcohol. I was buzzing.”

After a number of incidents of being hauled home or being hospitalized after passing out, Leach reached out to his parents for help. “I walked up to my mother-we were a close Catholic family, remember- and said, ’Mom, I need some help.’ ’What’s wrong?,’ she said. She didn’t know. I didn’t eat, I couldn’t hold a conversation, but she had no idea anything was wrong. I weighed under 100 pounds, looked like skin and bones, was paranoid, had deep, dark circles under my eyes, had blood pressure well above 200 systolic, couldn’t stop talking, didn’t make sense, dysfunctionally withdrew from everyone and everything, and she was still denying to herself that anything was wrong.”

So in 1964, Ed Leach, 19, was committed to his first private sanitarium. He was at last being treated for severe drug addiction. At the sanitarium, he was the only person with a drug problem in the midst of patients with catatonia and other mental disorders. He spent seven weeks there, and when he was released, Leach recalls, “The doctor told me, ’You can drink, but not too much. Try not to use amphetamines… but if you have to use them, don’t use too much.’”

He went back to the university, telling himself that he would never, ever, ever use speed again-he was convinced that it was the worst drug known to man-but he would drink. He went on wild drunks. One night, he borrowed his girlfriend’s car. When he came to a spot where policemen were stopping traffic, he floored the accelerator. The policeman in front of him managed to get out of the way, called for help and jumped on his cycle. Several miles later, the police stopped him and dragged him out of the car. Leach fought wildly, so they pulled out their jackknives, beat him up with billy clubs and hauled him off to jail.

A week later, his parents pulled enough strings and paid enough money to get him out of El Carmen, the Mexican penitentiary. After a number of other such incidents and one hospitalization for injuries received during a blackout, Ed’s father hinted that it might do his son a world of good to go into the service. Leach wanted to be a tough guy, so he became a paratrooper.

“The irony of it was that I was and am terrified of heights. I jumped out of an airplane 49 times, and not once did I enjoy it. But just being a paratrooper wasn’t going to be enough. The macho hero of my ideal had an image: He wore jungle fatigues, a pistol belt, shades and a green beret. I had just read the book, and I knew it would be the limit if everybody could see me as a Green Beret.”

In the service, Leach no longer drank whiskey, just cases of Thunderbird wine. He was also “smoking dope, taking speed and doing whatever came down the pike.” After he assaulted some military policemen, he found himself in his second mental ward-in a straitjacket this time. But he conned the army psychiatrist and a new commanding officer into dropping the charges and avoided a general court-martial.

When Leach completed his training as a Green Beret, he was assigned to Panama. “I was bilingual and had a top-secret clearance, so I was made an undercover agent. I was commissioned to wipe out drugs in Panama. Of course, I was the biggest dope-head in the whole country. I was totally chemically dependent. I went around with uppers in one pants pocket and downers in the other. If the heat got too close to me-if I felt I was in danger of being found out-I would finger somebody else.” From 1967 to 1968, he had a $150-a-day habit.

While he was in training for the Green Berets, Leach married Connie Collbaugh. “Connie was kind of picked for me-she was the good Catholic girl. We were from the same world. She had lived all over while her father worked for the United Nations. We met in Mexico, where her father was head of exploration and development for ASARCO.

“Connie came to Panama with me. There were times I couldn’t get out of bed, so she obviously knew about my drinking. I was more secretive about drugs. But she was powerless to do anything about it.”

Finally, Leach’s friends began to realize that everyone was getting busted except him, so the heat started coming down. Leach volunteered for Vietnam. “It seemed like a safer place to be at the time.”

But during his training to go to Southeast Asia at Fort Lewis, Washington, Leach met a Swede named Knut who introduced him to another chemical experience: LSD. “Hallelujah! When I had a taste, all I wanted to do was wait out my time to get out.” Leach was scheduled to go to the Cambodian border, but he refused to sign the intention to re-enlist.

After his discharge, he went back to Mexico, but his behavior was so aberrant that everyone except Connie refused to have anything more to do with him. So one day, he and Connie got on a train with a suitcase and 11 grocery sacks full of belongings and headed for Houston, where they had a few acquaintances. From July 1969 to March 1971, Leach drank continuously. He stuck to alcohol, since he had no drug connections in Houston. (He had purchased uppers and downers in Mexico over the counter.)

During this period, Leach would get a job only to lose it after a short time. He weighed 220 pounds and looked like a 50-year-old in his double-breasted suit and Peter Max tie. He got into trouble repeatedly-one time he blacked out and woke up in the Los Angeles airport. He even lived on skid row for a while. “I loved it. There’s no responsibility. You can snub your nose at society and everything it stands for. It is a way of truly getting into despair. The only reason I didn’t stay was Connie.”

Connie was working as a secretary in the pathology department at the Baylor College of Medicine. She had also started going to Al-Anon. This period was the height of Ed’s paranoia. “I locked myself in our apartment, took the keys away from Connie and bolted the door. She had to crawl in and out of the house through the window. If I heard voices outside the apartment, I would crawl into the bathroom and hide.”

One day in March 1971, Leach finally called out for help. He telephoned Connie at work and freaked out. He’s not sure it was a conscious decision to change his life; he doesn’t even remember doing it. But Connie came home and had Leach admitted into the Veterans Administration hospital in Houston.

Ward 212-the top-security psychotic ward-represented the end of the line to Leach. “I was locked behind four doors with only a mattress on the floor, although I was too sick to be violent. There were crazy people all over the place; they were screaming and whimpering. There was a terrible sense of hopelessness-the despair was contagious.”

On Ward 212, Leach was treated by a psychiatrist, who, he believes, was typically uninformed about substance-abuse problems. But finally, Leach asked to be switched to the alcoholic ward, and to his surprise, his request was granted. In the new ward, he spent three and a half months under the treatment of Dr. George Valles, who, Leach says, helped him immensely.

After being dismissed from the hospital, Leach became very involved with Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and took a job at Weiner’s department store in Houston. Sixteen months later, he went on his last binge (he now calls it a kind of cowardly attempt at suicide) and ended up one last time in a padded cell. “This time, I came out really defeated.” he says. “I just asked God somehow or other to help me stay sober-and I have been sober ever since.”

He went back to AA and determinedly applied its principles, admitting that he was powerless over alcohol and that he needed help from a higher power and from other people. He went back to school at the University of St. Thomas, a Catholic college in Houston, on the GI Bill. Before, he had flunked out of college for seven straight years. This time, he graduated with honors in a year and a half.

In college, Leach became involved with the Palmer Drug Abuse Program (PDAP), which Bob Meehan founded at the Palmer Episcopal Church in Houston in June 1972. When Leach graduated from college in 1974, he went to work full time for PDAP for $50 a week-less money than had been coming in under the GI Bill.

“I just knew that was what I was supposed to be doing,” he says. “I realized that I had to share what I had been given: sobriety. At that time, money and power meant nothing to me, although these were intoxicants that later contaminated me.”

Ed and Connie’s marriage had become rocky. “One thing about abusing either alcohol or drugs is that it masks a lot of other issues. That’s why so many couples experience marital problems after sobriety. I remember telling Connie in agony about this time, ’I keep having the feeling that you want me drunk.’ She admitted that way down deep she did, and she couldn’t understand why. Very often, the spouses of recovered alcoholics don’t know how to cope with their new independence; they’ve become hooked on the spouse’s dependence on the stuff and on them. Through Marriage Encounter and other experiences, we survived the change, but many marriages don’t.”

People had always told Leach that he was gifted, but PDAP was the first positive project he had sustained. PDAP was organized as a group program for 13- to 16-year-olds, but older people were always around. Meehan asked Leach to form a group for the 17- to 25-year-olds, and he started with about 50 people. Ten months later, the group had grown to more than 400 kids, with 100 parents associated.

When a group of parents from Dallas requested help, Meehan asked Leach to set up a program here in February 1976. Leach says, “Our success in Dallas was phenomenal . Our third banquet here was attended by more than 1,000 people. I raised a lot of money; the business community and I developed a love affair.” Leach had been here for two years when a 1978 issue of D listed him as one of the 78 most interesting and influential people in Dallas/Fort Worth.

In October 1979, Meehan asked Leach to return to Houston to become national executive director of PDAP. Meehan’s title became “founder,” and he still had the final authority. During that period, Carol Burnett’s daughter, Carey Hamilton, came to Houston for PDAP treatment and went public about it. Soon, People magazine published a story, Meehan went on the television circuit (appearing on Donahue and other shows) and Burnett talked about PDAP on several talk shows. The Houston office began to receive 450 telephone calls a day.

All this publicity called some unwelcome attention to PDAP, however. Some disaffected former counselors contacted reporter Charles Duncan of WFAA-TV in Dallas, who investigated charges that PDAP controlled and destroyed people. Leach recalls, “I didn’t know how to handle a hostile interviewer, so I got mad and blew it. He went after PDAP, accused it of being a cult, showed Bob as a guru and tied me in a bit.”

Then 60 Minutes and 20/20 got hold of the story. Just after the 1980 Super Bowl between the Rams and the Steelers, 60 Minutes broadcast a story that amplified the previous charges and also delved into charges of conflict of interest on Meehan’s part, alleging that he was acting as a highly paid consultant to the hospitals to which PDAP was referring patients.

“Bob was off in California trying to set up a PDAP program with Carol Burnett and her husband, Joe Hamilton, and I was left holding the bag in Houston. I went into a room to watch a videotape of the 60 Minutes show, and I realized that some things had to change, and yet I felt a great loyalty to all those who had gotten involved. What could I do? If I had quit, it would have been running away. So I stuck around, trying to do what I could to patch things up.”

Leach and Meehan were soon locked into a confrontation over PDAP. After the bad publicity, the money dried up. About 5,000 people were enrolled in the program, and there was a payroll of $120,000 a month to meet. The usual donors were reluctant to help, so Leach talked to people from a large hospital holding company, and they offered a blank check. Although he now thinks it was very poor judgment to do so, Leach took the offer to the national board of PDAP, the members of which all resigned in the face of this new conflict of interest. During the next four months, the hospital corporation gave more than $1 million to PDAP.

Meanwhile, a showdown between Meehan and Leach about the leadership of the program ensued. They and their followers isolated themselves for three days to try to work things out. The resolution they took back to the board was that Meehan would stay involved with PDAP and that Leach would start his own program; but when the board met, it sided with Leach.

“Prior to this, I had tried to convince myself that the money situation was okay, but I had stopped believing in it and had to face it. At the next meeting of the board, I told them we couldn’t take any more money from the hospitals-and there would be no consulting for extra fees. Each local board would be responsible for raising the money to take care of its program. Miraculously, we survived.”

The organization of PDAP went through a huge crisis. There were resignations and broken marriages. Some people went out and got loaded. There were even death threats and vandalizations. Leach and his cohorts began to reform the boards and created a training program for the counselors. More involvement from the professional community-doctors and psychologists-was sought, and the national headquarters was moved to Dallas.

For two years, Leach and his associates rebuilt the program, regaining the trust of community leaders and expanding into many more states. The climax of the public rehabilitation came when Nancy Reagan attended the 1982 PDAP national convention and endorsed the work of the group.

But for Leach, the new success had its costs. He lost much of his belief in the way the program works, and his private life suffered as well. He says, “Like AA, PDAP is a 12-step support program. You acknowledge your dependence on alcohol or drugs and acknowledge that you need help to stay free. But people have sometimes become dependent on the programs themselves-or on a guru, if the program is not well-run. By 1982, PDAP was a good, healthy support group again, but there are always elements who want to make such a program more than that, to have it perform functions it can’t or shouldn’t bear. I wanted something that would finally set people free, something more.”

The last years at PDAP were devastating to the Leaches’ marriage. “Connie wanted me out of PDAP; she couldn’t handle my involvement and what it was doing to me, so she divorced herself emotionally and just took care of our two kids. Out of self-protection, we both put our relationship on hold. Each of us was alone in our own household.”

Leach’s life was at a low point. In September 1982, he and Connie separated. In November, he left PDAP. He was without a wife, without his kids, without a home, without a job. “In my heart of hearts, I knew I was fouled up and would have to face the issues at some point. I thought I was burned-out and would never be able to help anybody again. A big part of me just wanted to get drunk and die. I just stayed around the house all day, shell-shocked.”

About that time, Dallas developer Jim Williams, whom Leach had met when he gave a lecture at the Hockaday School in 1976 and who had served on the PDAP board, repeatedly asked Leach to go with him to a businessmen’s Bible study that he led every Wednesday morning. Leach had always been spiritually involved, but not with conventional Christianity. His friends say that he was “cosmic,” constantly delving into ideas like reincarnation. But since he had little else to do, Leach went with Williams.

There, he met John Tartaro, who was just beginning to develop his ideas for a program that would help people change their lives and give them new directions. (Tartaro had been a motivational consultant for corporations, and, prior to that, had been the creative director for advertising at CBN in Virginia.) Ed and Connie joined the first group that Tartaro enrolled in his new program, which was then called Transformation Scripting.

Williams and Tartaro also kept after Leach about religious issues, and in 1983, Leach experienced a conversion to a more orthodox Christianity, becoming involved in a prayer group at St. Patrick’s Catholic Church. Meanwhile, he realized that the technique Tartaro was developing might be useful in the substance-abuse field. “I had decided to get out of the field, but I found that this was what I had wanted all along- a technology that gives people the ability to take control of their lives.” So Leach and Tartaro founded the New Place Program, based on the ideas Tartaro had developed and Leach’s experience in the field of substance abuse. Archer Simms, who had known Leach for years, quit his job as director of PDAP in Pittsburgh and joined the staff as soon as he was asked, even though at the time there were no offices, no clients and no way to meet a payroll.

Trust-Scripting, as the program was renamed, involves examining one’s goals in every area of one’s life-from basic value systems to work and recreation-and talking about where one wants to be. Among the exercises that help people achieve these goals is “Pruning and Trashing” in which the participants are challenged to deliberately (and almost arbitrarily) change some aspect of their life for a set period of time. Each day for 40 days, the participants open an envelope that contains instructions for some activity to be done that day. The activity may range from throwing away an unwanted possession to giving a special gift to a friend.

Although the initial reaction to the Trust-Scripting ideas might be that it sounds like hocus-pocus, those who have been through it at New Place Program are enthusiastic in their praise. Rob, for example, says, “It gave me some ideas, got me thinking about myself and what I wanted to do with my life. I’ve really aged under this program.” His mother adds, “He has emotionally matured about three years in two weeks.”

In addition to the Trust-Scripting sessions, New Place Program provides individual counseling sessions and group sessions, along with the support group meetings, for an intense period of eight weeks. The program is designed to support clients for a total of a year, then send them off with its blessing. Since the program has been open officially for less than one year, it’s too early to judge its success rate.

“I’m going to be controversial here: In AA, you’re an alcoholic forever. I spent years saying, ’I’m Ed, I’m a recovering alcoholic.’ I don’t say that today. I’m well, and I’m not going to get drunk. It’s the same with being a dope fiend-I’m straight, and I’m going to stay straight. In AA, there are some days you just hang on by your fingernails, willing yourself to stay sober. I call it white-knuckle sobriety. AA is a wonderful program, and it has helped more people than all the other programs combined, but it doesn’t have to be like that. If I acknowledge my addiction, I acknowledge that I am recovered.’’

Several of the first people hired as counselors at New Place Program, which is licensed by the Texas Commission on Alcoholism, had been very involved in AA. They found it difficult to adjust to the differences between the two philosophies, so they left NPP. Although New Place Program doesn’t claim to be religious in nature (like AA and PDAP, it does posit “a belief in God”), one of the two women hired as a counselor is an ordained Methodist minister who was trained at the Yale Divinity School, and the other is an Ursuline Catholic nun.

In a group session, Leach immediately interrupts anybody who says, “I need…” He tells them that the New Place Program is not about needs-there are millions of people out there who need to be sober. NPP is about wanting. “I don’t think this place is for everybody by any means. This is for people who want to change.” The big metaphor at New Place Program is “going from the old movie to the new movie”-changing one’s old image of oneself and one’s life and living with new images. The only insult at NPP that’s worse than “You’re living in the old movie when you say that” is “That’s a flat-world concept.” A flat-world concept is believing an old-fashioned, limiting idea because you have always believed it.

Among the people who have “gone straight” during the program’s short life is a young woman who was the only female disc jockey at two local rock radio stations. She had been taking drugs since she was 12, and recently her cocaine habit had begun to make work and life impossible. With the cooperation of the radio station, she checked into a local hospital that specializes in alcohol and drug treatment. She had only been out of the hospital for two hours when she was doing drugs again-with a couple of her fellow patients. Finally, her psychiatrist recommended that she try the New Place Program. She says it has helped her make the changes she wanted to make in her life, but those changes have necessitated other, unforeseen ones-such as quitting her job in radio. “It was like an alcoholic trying to work at a bar,” she says. Today, she is straight and is trying to decide what to do with her life.

Another program member is Steve Mallow, who was president of Cutter Bill Western Wear until November 1982. Mallow, 35, had been drinking every weekend since he was 15 and believes that he was an alcoholic by the time he was 25. He started using cocaine in 1979, and by 1981, he had a $l,000-a-week habit. He had been featured (favorably, in this case) in a 60 Minutes segment on Western wear, and his picture had been on the cover of the Southwest Airlines magazine. But, because his problem had become so bad, his wife Cathie, decided to take their 18-month-old daughter and leave. Mallow had been in Baylor Hospital, Denton State Hospital, AA and PDAP, but the longest he had stayed sober was three months.

Cathie had gone through PDAP herself during the Carey Hamilton period. There, she learned that Ed Leach had started a new program. She told Steve about it, and now he says, “I’ve got all the things I really wanted but never knew how to go about getting. Not only have I stopped the drugs and alcohol, I have lost 20 pounds, quit smoking and quit my job as a manufacturer’s rep. The old movie was that on the road you do drugs and alcohol.” He’s so enthusiastic about the New Place Program that he is helping to set up a residential inpatient facility, which he will supervise.

Leach and Tartaro expect to double their client load every three months. New Place Program, unlike PDAP, is set up as a profitmaking corporation, although its founders also hope to set up a non-profit wing for research and development, training and education. (NPP is negotiating with several school districts in the area to set up educational programs within the schools.) Leach says, “We set it up as a for-profit group so that those of us who are involved as the foun-dational employees can own it, manage it and have the flexibility to hire others as we see fit. Also, it’s very clear to us that having to pay is therapeutic; it means that people take what they are doing seriously. But also, in cases of need, money is not an issue. There’s a sliding scale, and nobody is turned away because of money.” That would seem to be a good policy, since so many of the clients seem to feel it is necessary to change their environments-and jobs-in order to keep the drugs and alcohol out of their lives.

Tartaro says, “This whole program is based on attitude modification along with behavior modification. Lots of people are at the top and miserable because they haven’t looked at their basic attitudes.” Leach adds, “Substance abusers are frustrated, hurt and in pain. They don’t know that there is another alternative. We’re here to show them that there is another alternative and that it can work for them.”

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Sports News

Greg Bibb Pulls Back the Curtain on Dallas Wings Relocation From Arlington to Dallas

The Wings are set to receive $19 million in incentives over the next 15 years; additionally, Bibb expects the team to earn at least $1.5 million in additional ticket revenue per season thanks to the relocation.

By Ben Swanger

Arts & Entertainment

Finding The Church: New Documentary Dives Into the Longstanding Lizard Lounge Goth Night

The Church is more than a weekly event, it is a gathering place that attracts attendees from across the globe. A new documentary, premiering this week at DIFF, makes its case.

By Danny Gallagher

Football

The Cowboys Picked a Good Time to Get Back to Shrewd Moves

Day 1 of the NFL Draft contained three decisions that push Dallas forward for the first time all offseason.