The markers at the crossroads do not denote what happened here, but rather what will. All around the intersection of Independence Parkway and Carpenter Road, wooden stakes with red flags signify the boundaries of lots that developers have carved out of the black Texas prairie land.

The markers are prophetic: The now-barren crossroads will soon be surrounded by the type of stylish brick houses that have already sprung up a few hundred yards away. Soon, this will be another busy juncture in a burgeoning suburban Utopia. But the significance of this spot lies not in what will be built here but in what was destroyed. For it is there, on a gently curving concrete esplanade, that something happened that would trigger a series of tragedies sufficient to cause the words “suburban Utopia” to have a hollow, painful meaning for the people in Plano for years to come. There are no markers to commemorate the event; it’s something the people who live here would like to forget.

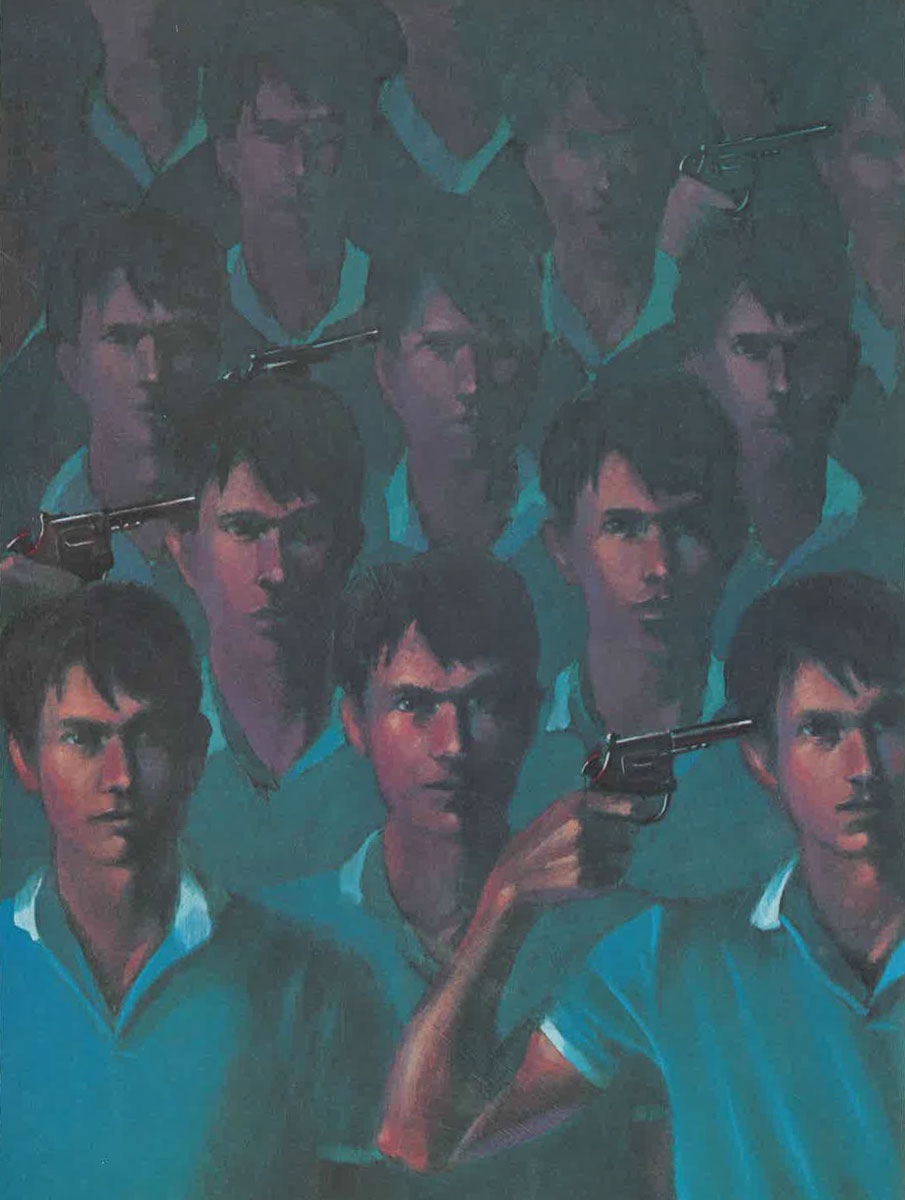

Their friends called the boys the two “B’s”: William (Bill) Ramsey and Bruce Carrio. Both were 16, blond and intelligent, and they seemed bonded together by that ongoing identity crisis called adolescence. The particular identity that appealed to the two B’s was the “cool” countenance: rock ’n’ roll, leather jackets, hip talk. They gave their friends the thumbs-up “Fonz” sign when they passed them in the halls of Plano Senior High School.

In keeping with their cool identity, the two B’s fantasized about fast cars. Even though Bill’s vehicle was a Ford Econoline van and Brace’s was a 1972 Buick Skylark-neither a match for the new Pontiac Trans Ams and Camaro Z28s that dotted the high school parking lot-the boys dreamed of drag racing.

The conversation turned to drag racing one Saturday night last February when the two joined their friends at a pizza parlor in northwest Plano for a birthday party. They invited a third friend, Michael Chris Thornsberry, to drive with them to the north end of Independence Parkway for a race. Thornsberry was just 15 and was driving with a learner’s permit, but he had a 1973 Corvette-a fast car. The race promised to be like something out of Rebel Without a Cause.“I can’t go on living with the pain…”

Scott Difiglia in a note to his parents

The spot they chose for the race had the advantage of being completely deserted at night. Concrete privacy walls shielded it from the view of the few occupied houses in a nearby subdivision. It had the disadvantage of being slightly hilly and curved.

Bill, whose van wouldn’t start that night, was the flagman, standing in the 40- foot-wide grass median in the middle of Carpenter Road. At his signal, the two cars raced westward down the road: Bruce in the westbound lane, the north half of the street; Michael in the eastbound lane. But as the speeding cars neared the finish line, Michael lost control of the Corvette, ran onto the median where Bill was standing and hit him before he could get out of the way.

Bruce, hardly able to believe what had just happened, loaded his friend into his Buick and drove him to the hospital. Although doctors at Plano General Hospital connected Bill to life-support systems, he died at 5:30 Sunday morning of multiple injuries.

At first, it appeared that Bruce was adjusting to the loss of his best friend. Bill’s parents were as understanding as they could be under the circumstances, telling the news media that Bruce and Michael had gone through enough anguish and didn’t deserve blame for what had happened. At the funeral, Bill’s parents gave Bruce a wooden crucifix that had belonged to Bill.

When Bruce went back to school the next day, he seemed to have remarkable composure, telling his friends that he would see Bill again someday in a place where there was only sunshine. Bruce’s friends understood; he was referring to a song by Pink Floyd, one of the two Bs’ favorite rock groups. No one realized that Bruce intended for the sunny day to arrive that afternoon.

After school, Bruce drove to his parents’ colonial-style house on La Quinta, just a couple of miles south of where the drag race had occurred. He pulled his car into the garage, shut the garage doors and put a Pink Floyd tape into the car’s cassette player. The tape stopped when it wound down to its last song, Goodbye Cruel World.

When Lucy Carrio came home, she found her son lying in the back seat of the car. The motor was still running. Bruce was dead of carbon monoxide poisoning.

•••

The people of Plano might have been able to forget the deaths of Bill Ramsey and Bruce Carrio if the boys had been the last teen-agers to die there this year. But the funerals were not over.

Two days after Bruce died, Pat Currey came home to her Richardson residence to find her 18-year-old son, Glenn, a senior at Plano High, slumped in the front seat of his blue 1966 Mustang. The radio was blaring. The garage in which the car was parked was closed. The motor was running. Glenn Cur-rey was dead.

Not long before his death, Glenn had broken up with his girlfriend. He had been under a lot of pressure, trying to juggle the responsibilities of a job, his school work and an emotional relationship. His parents knew that he was under a lot of stress, much of it self-imposed, but no one had suspected he was considering suicide.

When Glenn died, people in Plano started using the word “epidemic” to describe what was going on in their city. Parents wondered whose son or daughter would be next.

In a situation like this, the people of Plano are the last people in the world to simply wait and see what happens next-people get to Plano by being the quintessential achievers. This tidy little bedroom community of 86,000 didn’t earn its $37,000 average family income (more than 50 percent higher than the national average) because its residents were passive about life.

Plano is a city that gives definition to the term “upward mobility.” Its residents, for the most part, are not old-money ultra-affluent, but rather middle- and upper-middle management types who have clawed their way up the corporate ladder and used second mortgages and wraparound notes to buy themselves a spot in a pastoral setting 20 freeway miles from the problems of inner-city Dallas. They are ultra-achievers, and they have passed that legacy along to their children, who, in turn, have made the Plano Senior High School Wildcats perennial victors on the football field (four district football championships in seven years) and in academic ranks as well (10 National Merit Scholarship finalists among last year’s senior class).

Most Plano residents have worked hard to put their families into what they consider a suburban paradise. As soon as Glenn Cur-rey died, they began to perceive a threat to that paradise. Worried mothers got on the phone. School officials, guidance counselors and private-practice psychotherapists were swamped with calls from concerned parents.

“I’m worried about my son,” a typical caller would say. “He’s been withdrawn lately, and I just don’t want him to end up like that poor Currey boy.”

But the ultimate answer to the parents’ questions was frustrating to callers and counselors alike. The ultimate answer is that there isn’t an ultimate answer to why anyone-least of all, an adolescent-commits suicide.

Mark Fisher, executive director of the Suicide and Crisis Center of Dallas, sums up the situation well: “Suicide has been studied and restudied literally thousands of times over the past hundred years or so. And although we have a lot of small answers, we still don’t have the big answer. We still don’t definitively know why the hell people kill themselves.”

Plano parents, eager to see something done about the situation, did get some consolation, though. On April 1, a month after Glenn Currey died, a crisis hot line was opened. Parents held their breaths and waited.

They didn’t have to wait long.

On April 18, a ninth-grader at Plano Junior High School was added to the list of fatalities. Henri Doriot, 14, who had pinned newspaper clippings about Bill Ramsey’s and Bruce Carrio’s deaths on his bulletin board, sat in his room and cradled a .22-caliber Winchester rifle between his knees, aiming it at the center of his forehead. His stepmother and sister ran upstairs when they heard the shot. He died a short time later.

Henri’s father told Plano police that his son was a very emotional person and that he knew the boy had been thinking of suicide. But, obviously, Henri’s parents didn’t think he would actually kill himself. He left no note.

•••

With the death of Henri Doriot, the grief, anxiety and questions of the people of Plano began to increase exponentially with each day. If this was an epidemic, when would it stop? How would it stop? Why did it start? Why Plano? And, most important, the central question of every parent went unanswered: Whose child will be next?

The salient irony of the anguish that Plano parents were beginning to experience hits the heart of the reason that most of them moved there in the first place. Plano is, among other things, a textbook example of what has been labeled a “white flight” community (Plano Senior High School is 96 percent white). One of the primary reasons that people move to Plano is the city’s excellent school system. People make monetary sacrifices to live in places like Plano. They fight the freeways and pay the mortgages because their sacrifices buy them the security of knowing that their children will be enrolled in the Plano Independent School District. They come because they want their children to grow up in a safe environment. The overwhelming irony that began to dawn on them this year is that in doing so they may have brought their children to an environment in which they are more likely to kill themselves.What we seek to create for ourselves in a suburban utopia is a world without pain. In doing that we impair our ability to deal with pain when it inevitably does occur.

Mark Fisher, Executive Director, Suicide and Crisis Center of Dallas

The paradox of self-inflicted death in a man-made paradise raised questions that have been felt far beyond Plano, of course. Plano isn’t just a town; it’s an example of a contemporary American dream: an affluent community where all the lawns are mowed and all the problems of the big city are left behind. There are dozens of other Planos in America-towns with names like Hillsbor-ough, California, and Bethesda, Maryland -places where the pursuit of happiness is an obsessive undertaking.

Since Plano is not unlike many other American communities, the third teen-age suicide to occur there in two months began to attract national media attention. In its August 15 issue, Newsweek dissected the Plano lifestyle in a three-page story with the headline, “An idyllic Dallas suburb is discovering the sorrows of rootlessness and isolation.” Doubtless, Newsweek readers in comfortable suburbs across the country began to ask themselves the same questions Plano parents had been asking since February. About fourteen Americans under age 21 commit suicide every day; roughly 50 times that many try to and survive. Whose child will be next?

Three days after the cover date of the Newsweek report, Steven John Gundlah and Mary Bridget Jacobs, both 17, drove to a new house at the corner of Virginia and Emerson in far northwest Plano. The partially completed subdivision was a perfect place for teen-agers to go parking. But Steve and Mary had other plans.

They drove Steven’s 1975 Chevrolet up the alley and into the rear-entry driveway of the house. They raised the mustard-yellow garage door, drove inside and closed it. A construction worker found their bodies at 8:45 the next morning when he came to work on the house. They both left notes to their parents in a notebook.

“We both love you very much,” Steven wrote. “I couldn’t go on living without Bridget, so we’re both leaving together so we’ll always be happy.”

The events of the following week would give the epidemic theorists in Plano plenty to talk about.

Scott Difiglia, just like the 2,300 other students at Plano Senior High School, was searching for an identity. Kids like Bill Ramsey and Bruce Carrio chose the “cool” look, but Scott opted for another popular campus identity: the Urban Cowboy look. He drove a pickup truck, wore a gimme cap and carried a snuff can in his jeans. Acting the cowboy is a popular lifestyle at Plano Senior High School. Pickups are as ubiquitous on the school parking lot as hot rods and vans.

Like so many other high school kids, Scott was struggling with more than just the establishment of his identity. Near the end of the school year, Scott and his girlfriend had broken up. The girl had started dating someone else. He grieved over the loss of the relationship, but he hid his pain from his parents. They had no idea what was about to happen.

In mid-August, he told his former girlfriend that he was going to commit suicide with a shotgun. A week passed and nothing happened.

On Monday, August 22, six days after Steven Gundlah and Mary Bridget Jacobs died, Scott decided he had had enough. He called his former girlfriend and told her that he was going to commit suicide and that he was leaving a gift for her. She rushed to his Tudor-style brick house on Buckle Lane, just a few blocks off Independence Parkway. She arrived too late. Scott was lying in a pool of blood with a .22-caliber rifle beside him.

He was taken to Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas, where he lived until about 5 p.m. the next day. He left two suicide notes: one to his parents; one to his girlfriend. Both notes stated that he couldn’t live with the pain of being broken up with his girl. In his pickup truck, along with a note, was $200, his parting gift to her. Scott was 18 years old.

After this death, the national media descended on Plano. Dr. Glenn Weimer, a Plano marriage-and-family counselor who is working with the training of volunteers for a Plano Crisis Center, was interviewed by 50 reporters during the week after Scott became the sixth Plano teen-ager within six months to take his own life. Their queries were varied, but reporters asked one central question: What is it about the Plano lifestyle that caused the kids to kill themselves? By extension, they were asking a larger question: What is it about this lifestyle, which all America either lives or strives for, that makes kids want to die?

By now, the people of Plano were raising a strident uproar. They were not only scared by the turn of events, they were enraged. “I think what parents in this situation find offensive, whether they would admit it or not, is that by killing themselves, their sons and daughters are committing an ultimate act of rejection,” says a Dallas psychologist who asked not to be quoted by name. “The parents have worked to build what they consider the perfect lifestyle, and their children are saying, ’No thank you. This lifestyle is so painful that I’d rather die.’ ” (Rejection theorists have some heavy psychological company: Sigmund Freud, who held that suicide was really internalized anger for someone else. The human psyche, Freud said, thinks of itself as immortal; when someone commits suicide, he is symbolically murdering the person or persons who anger him.)

Many people blamed the deaths on the news media. When one local television reporter went to Plano High to film a report, students stood before the camera and made obscene gestures. Their message was representative of what their parents were thinking: “Get out of here. Leave us alone.”

In the search for answers, many Plano residents were now coming forward to offer opinions as to where the community had failed. It’s because the parents don’t love their children enough, one preacher said. Hogwash, a social worker said, it’s because the parents don’t communicate enough. Others said it was because parents weren’t strict enough with their children. Still others said it was because parents were too demanding. But no one, of course, had the answer.

Emile Durkheim never set foot in Plano, but he wrote a book that hits the Plano issues right on the mark. The book, Le Suicide, was published in 1897. Many psychologists still consider it the definitive work in the field. Durkheim, who believed that suicide is a failure of society rather than a failure of the individual, contends that there is an inverse corollary between the amount of social integration of a culture and the number of people in that culture who commit suicide.

It is more difficult for the individual to feel a sense of identity within a homogeneous culture than within varied, heterogeneous culture. Durkheim used statistics to state his case. The Scandinavian countries, for instance, in which there is a distinct sameness, have always had higher suicide rates than “melting-pot” countries where there is more diversity of lifestyles. (Denmark and Sweden have traditionally ranked among the top five countries of the world in suicide rates. Austria, Switzerland and West Germany are the other three.)

Durkheim coined the term “anomie” to describe what he considered the root cause of suicide: a feeling of social isolation that one gets when he is unsure about his role in society, his identity. Durkheim’s theory begins to make sense when one listens to what psychologists like Weimer are saying.People don’t kill themselves because they read in the newspaper about other people killing themselves. Publicity did not kill those kids in Plano.

Judie Smith, Program Director, Suicide and Crisis Center of Dallas

“One of the biggest crises of adolescence is to determine the struggle to find out who you are,” Weimer says. “This is not just the case in Plano but everywhere. Kids will do anything for an identity, even if it’s a bad one. Kids would rather be the class hoodlum, for instance, than have no identity.”

To that you can pose a further question. Can you imagine a more difficult place to establish one’s identity than in the high school with the largest graduating class in the state, in a school where every one of the 2,300 students is competing to be “some-body,” where the standards of excellence make spots at the top incredibly hard to attain? Since there can only be one valedictorian and one starting quarterback, kids choose a lot of other ways to create an identity: punk-rocker, cowboy, surfer; there are dozens. Many kids define themselves through their relationships.

“They are defining themselves through who they go steady with,” one psychologist says. “What makes that tough is that the very nature of adolescence dictates that there will be lots of breakups. When kids lose these relationships, it’s more than losing a steady; it’s losing a grasp on who you are and what you are doing here in the first place. When you think of it, it’s a wonder there aren’t more suicides just for this reason alone.”

In Plano, the normal pressures of being a teen-ager are more pronounced than else-where. This is a community in which the average family has only lived for four years. Most Plano residents have never heard the word “anomie,” but they are the prime victims of it.

“There is nothing about Plano, Texas, that makes it some kind of doomed community. This could have happened in Hillsboro, California, or Malibu, California, or any of a hundred cities. What happened in Plano is in keeping with a national trend.”

-Michael Peck, psychologist and staff member, Los Angeles Suicide Prevention Center.

In Weymouth, Massachusetts, at a high school graduation ceremony, a 17-year-old student came to the stage and said, “This is the American way.” He pulled a pistol out of his graduation gown and shot himself.

In suburban San Mateo County, California, a student asked a teacher, “Do you have to be crazy to kill yourself?” When the teacher answered, he pulled a gun out of a paper bag and shot himself. He was one of 12 high school suicides that occurred in that county in one year.

Young Americans are killing themselves at a rate three times higher than that of 25 years ago. That represents the biggest jump in suicides of any age group. Suicide is the second leading cause of death (after accidents) among adolescents. Suicide, in general, has increased in America over the past few decades. An average of about 80 Americans commit suicide daily. Suicide accounts for about 1 percent of deaths in this country, and most experts say that percentage would be higher if doctors and coroners were more honest in reporting what is “accidental” and what is suicide.

If local residents kill themselves this year at the national average rate, 400 suicides will occur in the Dallas/Fort Worth metropolitan area alone. And if deaths follow national age patterns, 70 of these people will be under 21. Another 360 young people in this area will try to kill themselves this year.

If you listen to the professionals who call themselves “suicidologists” long enough, the Plano suicides take on a certain air of normalcy. The youngsters who killed themselves in Plano were members of four vulnerable groups: young, white, male (all but one) and affluent.

“I don’t want to take away from the gravity of what happened in Plano, but what happened there is very normal in terms of patterns,” says Michael Peck of Los Angeles, who has written several books on suicide and who directs the youth division of the nation’s oldest and largest suicide prevention center.

Affluent white males commit suicide more often than anyone else. (Divorced men over 45 are still the most suicide-prone.) “When you look back at the suicides, even during the Depression,” says Peck, “these were largely affluent white males or white males who had just lost their affluence. There was no increase in suicides in the Depression among women, black and poor people who were already poor when the Depression started.”

But all the statistical profiles still don’t answer the basic question: Why did those kids in Plano kill themselves? It is in the pursuit of the answer that one is in for a surprise. Behavorial scientists are talking old-fashioned values-morality-these days.

Peck sums up what has been repeated by a number of his colleagues: “In upwardly mobile homes, the pressures are greater to succeed, and there is usually less parental guidance. Being left alone to raise themselves is something that is very frightening to kids. In affluent communities, parents tend to think, ’We’ve arrived; we’ve put our children in a safe environment. We can relax and not worry about the kids so much.’ It gave them an excuse not to parent as much.”

“We are teaching our children to almost worship the concept of immediate gratification,” says Weimer. “And when they can’t get immediate gratification-when there is not a solution for every problem right now-they simply don’t know how to handle it. They are only following the example we are setting for them.”

It is not, as one minister suggested, that suburban parents don’t love their children enough, psychologists say. It is rather that what parents do out of love for their children often contributes to their feeling of isolation. “We are buying them their own color television sets,” says Weimer, “so they can sit in their rooms and watch them alone.”

“I doubt that many parents consciously don’t want to listen to their children,” says Fisher. “It’s just that somewhere along the way we’ve stopped listening. The result is the same.”

Ask enough social scientists what causes suicide, and you’ll hear the word “depression” a hundred times. Ask them what causes depression in teen-agers, and you’ll hear a lot of answers, but the recurring words are “isolation” and “pressure.” Parents put pressure on their children to succeed and, however unintentionally, contribute to the process of isolation that a suburban lifestyle can create.

“People who commit suicide do so out of a feeling of hopelessness, haplessness and helplessness,” Fisher says. “They kill themselves because they think that’s the only way to stop the pain, that there are no other options. That’s true for all age groups.”

With teen-agers, suicidologists say, the problem is compounded by the youngsters’ lack of experiences; they haven’t been around long enough to know their options.

This situation is further compounded by the fact that most teen-agers who are moody or withdrawn or who feel isolated are simply going through a normal stage of their lives. “We don’t really know what went on in the minds of those kids in Plano,” Fisher says.

How can a parent fight a problem so deadly and complex? It may not be as overwhelming as it sounds. Eighty percent of suicide victims give some kind of warning signs: giving away property, talking about death, talking about not having to worry about their problems anymore, witharaw-ing, acting restlessly. The signs aren’t difficult to spot. But most people who commit suicide don’t really want to die-at least, not at first. They send out cries for help, Fisher says. It’s when no one responds to those signals that they become convinced that the only option is to kill themselves.

The solutions are simple, but not always easy. “I tried to kill myself because I was convinced that my parents didn’t really love me,” says Rod Mason, a Dallas salesman who overdosed on pills when he was 14. “I was wrong, but I didn’t know it at the time. What my parents did to literally save my life is make me know how they felt about me. They started listening to me and dealing with my problems, and things got a lot better.”

“You can start by simply talking to your children,” says Judie Smith. “Be frank and honest with them. Don’t be afraid to use the word ’suicide.’ They are not going to commit suicide because you [say the word].”

And when they talk, Weimer says, it is important to listen. “Many parents just don’t want to hear that their kids would think of something like suicide, so they react defensively and tell their kids, ’You know you don’t mean it. You are not going to commit suicide.’ That just makes the kids feel more isolated than if the conversation never happened in the first place.”

Above all, psychologists say, parents who are worried about their children’s potential for suicide should not hesitate to seek professional help.

That type of help is becoming easier to get in Plano these days. About 40 volunteers are being put through a lengthy training course to operate a crisis center in Plano. (The crisis hot line that opened in April was simply a direct line to the Dallas center.) Plano schools are calling in speakers from the Suicide and Crisis Center.

Skeptics may say that these efforts are closing the barn door after the horses are gone, but professional counselors say that the majority of suicides can be prevented by simply getting counseling for those considering death. “The nature of crisis is that it is, by definition, temporary,” Weimer says. “There’s no reason to believe that the child who is counseled not to kill himself today will simply do it tomorrow.”

Kids, of course, are frequently in no position to realize that the pain of the moment will fade. They think, in the words of Scott Difiglia in his note to his parents, that they “can never be happy again.” The key to keeping these kids alive is showing them they can be happy again.

The basic concept that parents should convey to their children, psychologists say, is the idea summed up the motto of Dallas’ Suicide and Crisis Center: “We hear you.”