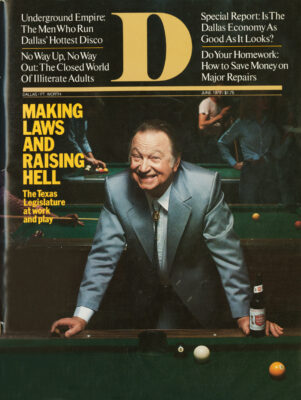

Although our conversation will be brief, it will have many interruptions. Billy Clayton is a busy man. He is not just any beer joint patron. He is the Speaker of the Texas House of Representatives, one of the most influential politicians in the state. And this is not just any beer joint. It is the Broken Spoke, a huge dance hall that fills up every Tuesday night with lawmakers, bureaucrats, lobbyists, journalists, and political hangers-on. On Tuesday nights the Broken Spoke is the court over which Clayton reigns. Most of the lesser politicians who come to the Spoke this night, and all of the lobbyists, come there to do obeisance. This is more than just a good time; it is a ritual of Texas politics.

“I’m trying to evaluate the effectiveness of the Dallas and Tarrant delegations,” I tell Clayton. “What do you think of them?”

’’Well,” says the Speaker, standing with one hand in his tailored vest pocket and the other wrapped around a can of Miller Lite, “those folks in Dallas and Fort Worth must have something going for them or there wouldn’t be so many of them.”

A tall man in a three-piece suit approaches Clayton and puts his arm around the Speaker’s shoulder, talking into Clayton’s ear so he can be heard over the country-western band which is droning away in the background.

“I told her you’d dance with her, Billy,” the man says. “Okay?”

“Sure,” says Billy Wayne. “You just send her over whenever you want to and I’ll be glad to dance with her.” Protocol. Patrons of the Spoke often bring their secretaries, their girlfriends, and sometimes even their wives. Many of the women want to dance with Clayton just to say they have. He is the man of the hour.

“Naw,” says Clayton turning back to me, “Dallas and Fort Worth have some real fine representatives down here. Your area is being real well represented.”

Another interruption. This time it is a man in jeans and a cowboy hat.

“We drove up here from East Texas to see you, Mr. Clayton,” the man proclaims. “We’d sure be honored if you can give us some of your time tomorrow.”

“You bet,” says Clayton. “You just come on up to the Capitol and have me paged on the House floor. I’ll be proud to meet with you; that’s what we’re here for.”

He turns to me. “You just come up to the House and have me paged,” he tells me. “I’ll be glad to talk to you anytime. That’s what we’re here for.”

Billy Clayton is a West Texas farmer with none of the polish an urban politician might bring to the state capital. What has taken Clayton to an unprecedented third consecutive term as Speaker of the House is his consummate ability to play the Austin power game. And for Billy Clayton, as for most of the state’s legislators, that’s the only game that matters.

If you think this year’s session of the Legislature was unproductive, you’re wrong. It was unproductive only if you evaluate the session in terms of how much legislation it actually produced. Even the most callow freshman legislator finds out quickly that in the legislative power game, getting bills passed is only one – and not necessarily the most important – way in which the score is kept. The major goal is simply to get ahead.

Some legislators may have gone to the capital because of what they wanted for their communities. But all of them went there because they had definite ideas about what they wanted for themselves. All have egos that can be satisfied only by honorifics like “Senator” and “Representative.”

“It becomes obvious rather quickly that this place is a club,” says Fort Worth freshman representative Reby Cary. “And, brother, if you’re not a member of the club, you’re just flat out of luck.”

Being elected to the Texas legislature does not make you a member of the club. It merely makes you eligible for admission. You can belong to the club, and ultimately use it to your advantage, if you abide by a few basic rules:

1. Rule One: The Lobbyists Are Usually Going to Win, So Why Not Lie Back and Enjoy Their Hospitality? More than any other year in this decade, 1979 is the Year of the Lobby in Austin. The reason is basic: Money talks. In Austin money screams, and the lobby has it. The Sharpstown banking scandal that rocked the legislature and gave business lobbyists a bad public image in 1971 is fading from the public memory. Because many power players believe that the election of a Republican administration means that business will win back some of what it lost in the consumer-protection era of the mid-Seventies, business lobbyists are coming back out of the capital closet.

The lobby groups build their power base at election time. That’s when it’s legal to pay your elected representative. Political Action Committees, or PAC’s, try to outdo each other at burying all the incumbents, and most of the strong challengers, in piles of cash. Example: In a two-week period last November, Bankers Legislative League of Texas (BALLOT) handed out $34,000, including $2500 to Lt. Governor Bill Hobby and $1500 to Clayton, who was run-, ning unopposed; an even-handed $5000 apiece to gubernatorial candidates John Hill and Bill Clements; and various $1000, $500, and $300 gifts to more than three dozen incumbent legislators. A financial report filed by BALLOT in April 1978, the month before primaries were held, showed that at that point the organization’s cumulative investment in election campaigns had reached $103,604.22. BALLOT, of course, is just one of several groups that represent the bankers’ interest in politics. And the bankers are just one of a host of interest groups that seem to have checkbooks with an infinite balance.

Both elected officials and their benefactors are quick to tell you that the gifts are given with no strings attached. “I’ve always been quite proud of my support from the business community,” says Irving Rep. Bob Davis, who is a favorite charity for the real estate, insurance, utility, medical, and dental special interests. “If they are giving me something out of any other motive than an appreciation for good government, then that is their problem, not mine.”

Special interest groups consider their contributions to be exactly what they are: an investment. During the last campaign, the realtors’ group, TREPAC, gave Eu-less Senator Bill Meier $10,000 in contributions. That one gift made up about 10 percent of Meier’s campaign financing. This spring, he introduced a bill which would effectively gut the Consumer Protection Act of 1973. Meier’s bill called for massive reductions in the damages a consumer who suffered from a deceptive trade practice could receive. (It also called for the consumer to prove deceptive representation and intent to defraud in order to collect damages in some cases.) TREPAC was in favor of Meier’s bill because under the Consumer Protection Act, realtors can be fined if they sell you a house with structural flaws they know about but conceal from you. A skeptic might think there was some relationship between the real estate lobby’s financial support of Meier and the Senator’s feelings about consumer protection.

Any legislator will tell you that the reason they made it illegal this year for you to buy keg beer from a distributor is that the big beer distributors and manufacturers determined that individual purchases of keg beer were costing them too much money. It was just too economical for the consumer.

The way the interest groups’ monetary power builds a base for their lobbyists is not as simple as it might seem, however. The Legislature is not like a retail store. You don’t just walk in and pick out who you want and buy him. The process, since the Sharpstown scandal of 1971, has become much more sophisticated than that. When special interest groups give money to every candidate in sight, they make a lot of friends. They build up a lot of subtle commitments. They also show an incumbent that they can use their checkbook power to help defeat him in future campaigns.

“I’d like to think the House and Senate members will listen to me because I’m a persuasive sort of guy and because I’m a good conversationalist when I take them out to dinner,” one of the more successful lobbyists in Austin told me one evening as we huddled in the corner of a small bar near the capitol building. “But I guess if I am really honest with myself I’d have to admit that they really listen to me because they know damn well that I say where the money goes at campaign time. “I’ve got a few clients with some pretty big bucks,” he told me. “And they don’t really want to keep up with this process themselves. It’s too much of a zoo. So I kind of keep up with things for them and keep them abreast of who their friends are in Austin. When campaign time rolls around, they naturally want to make a contribution to the people who are doing what they like to see done. There’s nothing sinister about that,” he added. “And I guess a lot of them probably realize that if they are really working hard against my clients’ interest that we will probably be in the mood to drop a few thousand on their opponents for reelection.”

The lobbyist told me that the power of the checkbook gives him a broad range of powers, including the “carrot or the stick.”

“Like anybody, I like to use the carrot,” he said. “Who wants to be a horse’s ass? A typical carrot method will be this: If a member will do something for me, I’ll go to one or two other members who we’ve supported in the past and I’ll ask them to give that member some help on one of his pet bills.

“I like to put people with similar interests together. I guess you could say I’m sort of a computer dating service in that regard. I’ve had a lot of success with that type of method.

“Sometimes I have to use the stick,” he said. “But please remember I never really like to. I’ve had real good results with this device: If you are really giving me trouble I can have Mr. Big from your home town call you and tell you how unhappy he is with your service.”

The lobbyists have a lot more than just money going for them in their relationship with the legislators. For one thing, the average lobbyist is usually more capable than the average legislator. The legislator is in Austin because he can win a popularity contest. He can get elected. That, as experience has proven time and time again, does not mean that the legislator is capable of doing anything in Austin when he gets there. The lobbyist, on the other hand, is chosen because he can get things done. Lobbyists in Austin represent companies like United States Steel, Exxon, and Dow Chemical, as well as the banks, the insurance companies, the retail merchants, and a host of other interests which have been successful because they hire competent, capable people. Lobbyists are paid better than the legislators, and they have more resources.

One lobbyist registered with the Texas Secretary of State’s office is Marion “Sandy” Sanford Jr., a Houston attorney who is ubiquitous in the capital power arena. The list of groups he is registered to represent in Austin reads like a corporate “Who’s Who”: Housing Authority of Houston, ALCOA, Texas Association of Bank Holding Companies, Home Life Insurance Company, United States Steel Corp., Shell Oil Co., Episcopal Diocese of Texas, Texas Eastern Transmission Corp. (a pipeline company), Houston Natural Gas Corp., Flour Corp. (an oilwell service company), Mitchell Energy Development Corp., Association of Executive Recruiting Consultants Corp., Texas Forestry Association, El Paso Housing Authority, Houston Apartment Owners Association, plus the cities of Garland, Denton, Austin, San Antonio, College Station, Brownsville, Lubbock, Weimar, Caldwell, Brenham, Hallettsvelle, Boerne, Gon-zales, Fredricksburg, Jasper, Robstown, Moulton, Lampasas, Hondo, Giddings, Cuero, Sonora, Grandbury, New Braun-fels, Luling, Bastrop, and Flatonia. One might safely assume that Sanford has sufficient connections and resources to make him more than a fair match for some legislator whose claim to his office is the fact that he used to be a television weatherman or that his father-in-law is the county judge.

The more skillful lobbyists do a much better job of keeping up with the various pieces of legislation than the legislators themselves. This is partly because the lobbyists have better resources than the legislators, and partly because a great number of the bills that are introduced in the legislative session are written by the lobbyists and merely handed to their favorite office holders for introduction.

Another reason the lobbyists are better informed about what’s going on in the legislature is their sheer numerical superiority. There are 3000 registered lobbyists in Texas. They outnumber the legislators by more than 16 to 1. (Texas has more registered lobbyists than any other state; twice as many as the number two lobby state, California.)

Many legislators rely on the lobbyists as sources of information. “I don’t think there is anything wrong with it,” says Rep. Bob Davis, “as long as you realize what the lobbyist’s interest in a piece of legislation is and realize what perspective he is coming from. You’ve got to remember there are lobbyists for both sides of an issue.”

Lobbyists make good companions for legislators. They will always laugh at the legislator’s jokes. They will always pick up the check at lunch or dinner. The lobbyists are everywhere. Smiling.

“If you let them,” says Rep. Cary, “the lobbyists will even follow you into the restroom.” Some legislators take the lobbyists’ largess to extremes. One of Fort Worth Rep. Doyle Willis’ colleagues credits him with inventing this device: A lobbyist comes to the representative with a bill to be introduced into the session. “I’ll be proud to carry your bill,” the legislator will say, “but I’m sure you don’t want me to do it looking as shabby as I do.

“This suit looks so worn out,” the legislator will say. “I think that if you really think about it you’ll probably feel a whole lot better about me carrying your bill if I’m wearing a new suit when I introduce it.”

It is common practice for liquor lobbyists to pass out certificates which legislators can redeem for a bottle of their favorite whiskey at any liquor store in the state.

When proponents of the fuel “gas-ohol,” a mixture of gasoline and grain alcohol, came before the Legislature seeking authority to manufacture the fuel in Texas, they passed out certificates to the House and Senate members that entitled the bearer to get 20 gallons of the fuel at an Austin service station. One legislator offered to buy the certificates from his colleagues for $5 each if they didn’t want to get the’ fill-up for themselves. That is typical Austin perk dealing.

The fact that the lobbyists have a whole arsenal of resources, ranging from tokens to multi-thousand dollar campaign contributions, makes them a formidable force in Austin politics.

“There is just no way I can express to you how frustrating it is,” Dallas Rep. John Bryant told me, “to see a piece of good legislation killed when the members just mindlessly vote it down, for frivolous, lobby-related reasons.”

Rule One is the principal reason why you won’t be able to buy panty hose or kitchen ware on Sundays, even though polls show that a majority of Texans want the state’s century-old blue law abolished.

“You still got your Sears and your big department stores who just don’t want to open their doors on Sundays,” says Dallas Representative Chris Semos, the chairman of the House committee where the blue law repeal bill spent most of the session gathering cobwebs. “The repeal movement is gaining a lot of momentum from your Kroger’s and such, but I just don’t think it has gained enough momentum to get anywhere yet.”

2. Rule Two: You Can’t Beat the System. In any other game, this would be Rule One. But in Austin, maverick legislators like John Bryant, who is anathema to the Clayton power team, can occasionally beat the system. It’s just that they can’t do it very often.

In the House, the Speaker is elected by his peers. He gets elected, of course, by a lot of going along and getting along, and by a lot of coalition-building. Clayton is not considered a strong leader, but he is the best at getting votes pledged to him. Once the Speaker is elected, he can build an empire. The Speaker appoints all the committee chairmen; they owe their allegiance to him. This gives the Speaker tremendous power because the bills that go through the House – and all appropriations bills must originate there – must first go to one of the various House committees. If the Speaker does not like your bill – or does not like you – it is a simple matter for the appropriate chairman to let your bill die in committee. It happens hundreds of times in every legislative session

Consequently, it’s of paramount importance to get along with the Speaker. In the current session, that gives rural interests the upper hand. Clayton is no lover of cities, so committees in the House are chaired either by rural representatives or by urban representatives who tend to go along with the rural interests.

“It really makes me mad,” Bryant says, “that so many of these urban people will come down here to Austin and immediately sell out the interests of their constituents just to get along with the power structure. It’s as if they place more of a premium on getting along and being liked than they do on looking out for the cities. But of course the rural people stick together like rocks, and the urban people frequently don’t even think of themselves as urban people.”

Clayton is a firm believer in the lobby system. Frequently the Speaker has attempted to reach a compromise on a legislative issue by getting together the lobbyists for the opposing sides and trying to get an agreement between them. The agreement would likely become law.

Because Clayton believes in the legitimacy of the lobby, he appoints committee chairmen who share that belief. “You’ll find,” says one veteran capital correspondent, “that all of the committee chairmen are lobby-oriented; if they weren’t, they wouldn’t be committee chairmen.”

The system works a little differently in the Senate. Lt. Gov. Bill Hobby, who presides over the Senate, is less heavy-handed than Clayton. He tends to act as if the majority of the Senate has a right to do whatever it wants. But just as in the House, the system puts Hobby in control when he wants to be. When presiding, Hobby can recognize (or fail to recognize) any senator he wants to. “There’s not too much question,” one capital veteran says, “that Hobby can get 30 votes on something any time he really wants to. The system dictates that.”

Rule Two is another reason why you won’t be able to buy panty hose on Sundays. The lobby in favor of the blue law has the upper hand over the lobby against the blue law on the basis of what may seem like an obscure procedure: It takes only 11 state senators to send a bill to the trash can. One of the senators who can gather 10 colleagues on almost any issue is Sen. Bill Moore.

“The lawyer who represents the retailers who want to keep the blue law is an old friend of Senator Moore,” Semos told me. “Moore would be willing to kill any repeal law that the House sends to the Senate. So it really doesn’t matter what we do in the House; the ball game is basically over right there.”

Because it is so difficult to beat the system in either the House or the Senate, it becomes important very early in a legislator’s career to let his colleagues know that he wants to be a part of the system, not an opponent. That’s why it’s important to frequent the Broken Spoke and the endless string of parties that are given for the legislators. In the Texas Legislature you’ve got to be one of the boys.

3. Rule Three: If Public Service Is a Sacrifice, You Just Don’t Know How to Do It Right. One of Rep. Bob Davis’ colleagues in the House likes to tell a story about how the bill that prohibits the sale of keg beer to individuals put Davis in a dilemma. “He told us he just couldn’t make up his mind on how to vote,” the representative says. “He said he had a neighbor who kept a keg around and let him drink beer from it in the summer, but he also said the Coors distributor has some of the best seats in Ranger Stadium.” Perks like those are nice, but they represent only the small legislative potatoes.

Despite the fact that legislators continually sermonize about how financially tough it is to serve the people, it can be very, very rewarding. And in perfectly legal ways. Many of the legislators are in businesses which can be materially affected by their service in Austin. Of the 181 members of the Legislature, 70 are attorneys.

It is perfectly acceptable for a legislator to represent a client before a state board or commission as a practicing attorney. Some legislators even defend the practice. State ethics laws stipulate only that if an attorney-legislator is representing a client before a state body in Austin, it has to be made a matter of record that the legislator is acting as the client’s attorney. Critics contend that perhaps a legislator, who votes on the funding of a state agency, might get listened to more attentively by the agency than some other attorney.

Sen. Meier, who has engaged in the practice, defends it staunchly. “You can’t say to [a legislator] that you have to be a part-time citizen-legislator,” Meier told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, “and when you get back home don’t take certain kinds of business if it’s going to take you down to practice law in front of a quasi-judicial body in Austin.” There are many other ways an attorney can profit from his public service. The vast majority of the bills dealt with by the legislature concern business regulation. Big businesses need attorneys. So do friends of big businesses. As one legislator put it, “So what’s so wrong if you make a few contacts who can maybe help you in your practice?”

Legislators have suprisingly little trouble getting a chance to buy into small oil and gas ventures. Some, like Meier and Hurst Rep. Charles Evans, own stock in savings and loan associations which, of course, are state-regulated. Twenty-one members of the House list their occupations as either realtor, investor, or insurance agent. All three are occupations in which it doesn’t hurt to know someone (like, for example, a lobbyist) from a big corporation.

When a legislator takes Rule Three too far, however, he can get his hands burned. Rule Three gave Austin the Sharpstown scandal. The 1969 session of the Legislature passed bills that would have enabled Houston financier Frank Sharp’s bank to get out from under the watchful eye of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. (The bill was later vetoed.) Several key members of the legislature, acting under Rule Three, had been given some extra nice financial opportunities by Sharp. When his bank fell apart, so did the legislators’ careers.

A large number of legislators go for smaller perks, like using their stateprovided operating expense allowances to rent offices in their home districts from themselves. It makes a nice way of getting part of your private office expenses paid by the taxpayers. Rep. Sam Hudson, who two years ago led the entire House of Representatives in public expense money spent, has his law office and his district office under the same roof, with the taxpayers picking up half the rent. The state pays $350 a month in rent for Rep. Frank Gaston’s office.

And if nothing else works, it is perfectly legal just to take money straight from your campaign fund and give it to yourself for living expenses. Sen. Ike Harris, a Dallas Republican, recently reported that he lent $22,600 from his campaign fund to “Ike Harris, attorney.” Harris explained that he had devoted so much time to public service in Austin that he just hadn’t spent enough time working as an attorney and putting bread on the table for himself. There is every indication that, at least in Harris’ case, there’s plenty more where that came from. “Ike has carried and voted for so much lobby legislation over the years that he could call in his chits and probably raise a million bucks,” says one capital observer.

Even though legislators are paid a salary of only $600 a month by the taxpayers, they are provided with an opportunity to advance to much higher-paying state jobs when their terms expire. Former Rep. Lyndon Olson of Waco, a Clayton crony, finished his legislative career with an appointment as State Insurance Commissioner, at a salary of $39,900 per year. Former Rep. Jim “Super Snake” Nugent, another appointee under Gov. Dolph Briscoe, now draws $45,200 per year as a member of the Texas Railroad Commission. Others, like former Rep. Sam Coates of Dallas, left the Legislature to become lobbyists. Coates represents Texas International Airlines now.

4. Rule Four: You Must Learn to Con the Media. Quick, who’s Carlyle Smith? Who’s Anita Hill? You probably didn’t know that both are House members from Dallas County. But everybody’s heard of Clay Smothers. The reason is Rule Four: Some members are better at conning the media than others.

An instance of skillful media manipulation occurred recently when Meier introduced his bill to slash the damages a claimant could receive under the Consumer Protection Act. The liberals, led by Austin Senator Lloyd Doggett, Garland Senator Ron Clower, and Galveston Senator “Babe” Schwartz, began a filibuster with only one goal: Get headlines.

Schwartz decided that since the real estate lobby was in favor of Meier’s proposal, perhaps Schwartz should read, from a computer printout, the name of every realtor in the state into the record. The process would not take more than a few hours. Senators who planned to take part in the little exercise ordered their staffs to go out and get bed rolls to place in adjoining offices.

As the filibuster progressed into the night, Doggett put on a pair of tennis shoes. Senate rules require that every man on the Senate floor wear a suit and tie. The rules say nothing about shoes. Tennis shoes and a suit, when worn by a state senator, make good pictures. After a few hours, Doggett retired into the hallway – for interviews. A crowd of reporters surrounded him. “I’ve fought for the people of Texas so long and so hard that my feet have just about given out,” he told the reporters. “I’m going back in there and keep after it as long as I can stand up.”

“Senator Doggett,” one reporter asked, “are you going to keep wearing those tennis shoes for the rest of the debate?” (Nobody ever said reporters were sophisticated.)

A few minutes later, I was standing in the American-Statesman press room while one of the paper’s photographers was talking on the telephone to his assignments desk.

“Yeah,” he said, “I got Doggett in the hallway outside the Senate chambers. Yeah, I got the tennis shoes in the picture.” Bingo, Senator.

I also had a first-hand chance to see Rule Four abused to the point of absurdity. One evening Sen. Clower gave me an interview that started at 10 p.m. at a place called the Chili Parlor.

Clower drank Lone Star beer from longneck bottles and played dominoes with a horde of staff groupies while he told me of the evils of the Legislature. The staff gave Clower good support, laughing at all his jokes and agreeing with every point he made. He said there was one basic problem: the lobby.

“Sen. Meier’s only secret is that he does exactly what the lobby tells him to do. All he’s doing is carrying the lobby’s bills. What’s so skillful about that?”

My look told Clower I was having difficulty swallowing it. Meier may be everybody’s vote for Mr. Lobby, but if he is, he was chosen by the lobby because he is skillful. Meier is nobody’s fool.

“I know that may sound like an oversimplification, but that’s the way it is down here,” Clower said.

“I’m wondering what you think about the lobbyists,” I asked Clower.

“Lobbyists are a bunch of turds,” Clower snapped. “Gene Fondren [the auto dealers’ lobbyist] is to the Legislature as Rasputin was to Russia.”

“Oh,” 1 said.

Clower shuffled the dominoes while I debated with myself about whether I should continue the interview.

“Okay,” I said, “if the lobbyists are really the bad guys, who are some of the biggies? I’ll chase lobbyists if you point me to them.”

“You better ask somebody else that one,” Clower said. “I don’t have any use for lobbyists. I don’t even talk to them.”

There was no Lone Star available in the Secretary of State’s office the next day. Nor were there any dominoes. But there was a financial report for an organization called “Friends of Ron Clower.” The principal function of the organization was to fund Clower’s officeholder account. During 1978, the organization transferred $13,093.17 into the officeholder account, the fund out of which Clower spent money for things like a charter flight to a Dallas appreciation party, rent and furnishings for an Austin duplex, campaign advertising, and refreshments from Dan’s Liquor Store in Austin.

Listed as contributors to Friends of Ron Clower are three registered lobbyists, one for the Texas Building and Construction Trades Council, one for the Trinity River Authority, and one for the Texas Workmen’s Compensation Assigned Risk Pool. Also listed as contributors are thirteen political action committees, including the Life Underwriters, Texas Credit Union, Morti-PAC (morticians), Lift-IV (trial lawyers), and AUTO-PAC. AUTO-PAC, which gave Clower $250, is the auto dealers’ political action committee. Its lobbyist is a man named Gene Fondren.

WINNERS & LOSE

Here’s how your legislator is playing the game R

emember, being a winner in the Austin sweepstakes doesn’t mean you’re a great public servant. It just means you know how to get things done. If it’s good tor the folks back home, that’s fine. What counts is if it’s good for you, politically and financially. These are Dallas and Fort Worth’s biggest winners and losers.

ROOKIE OF THE YEAR:

Governor Bill Clements.

He surprised a lot of people by getting elected in the first place; now he’s surprising a lot of people by being effective. When the conservative Clements was elected, the business-oriented lobby got the impres-sion that it was open season in Austin. His threat to veto the proposed increase in mortgage rates proved that their judgement was premature. His performance has caused Sen. Ron Clower of Garland to predict: “That man’s going to fool around and get himself re-elected. I don’t think you can say he’s going to be a one-term governor. ” That Clements is able to play the political game by his own rules makes him a good candidate for the biggest winner in Austin this year.

BEST HUSTLERS:

Bob Davis, conservative Republican, Irving. For Davis, a four-term veteran, the name of the game in the Texas House of Representatives is to join House Speaker Billy Clayton’s hand-picked team and play the lobby for all it’s worth. As chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, which must give its blessing to all tax proposals which pass through the Legislature, Davis has become one of the most powerful members of the House. Davis is considered one of the best legislative technicians in Austin. “He knows the rules backwards and forwards and he knows how to beat hell out of you with them, ” one of Davis’ adversaries says. “It can be really frustrating sometimes to have your bill clear committee when you know that Davis is just waiting to swoop down on it and use one of the loopholes in the House rules to stomp your bill into the carpet.” At election time, Davis accepts money from every special interest group in sight. During the session, he uses his connnections to skillfully advance his cause. His friends and his critics alike say he is arrogant and vindictive at times. Davis’ backers say he has as good a chance as any Republican has ever had of becoming House Speaker some day.

Bill Meier, conservative Democrat, Euless. The six-year Senate veteran is like a one-man taxi service for special interest groups, driving their bills directly through the legislature and then going back to pick up more. Meier, who has been dubbed the “black knight of the Senate’’ by the Austin media, is a winner because he is very successful at what he does. ’’ You can give most people in the legislature a bill to carry for you, ” one lobbyist says, “and they’ll waffle along with it just enough to earn their keep. But Bill Meier will get in there and fight to the death for a bill. ” His projects this session have included attempts to gut the state’s consumer protection law and increase mortgage interest rates. Meier has put himself in position to have considerable financial support – from the lobby – for a crack at a statewide office.

Ron Clower, liberal Democrat, Garland.

Clower’s politics put him on the opposite end of the spectrum from people like Rep. Davis, but the two men have one thing in common: They are skillful players. He’s followed the liberal’s road to success, keeping a high media profile and being quick to criticize the status quo. The strategy has worked well. As chairman of the Senate Subcommittee on Consumer Affairs and as the leader of an investigation into the Bell Telephone Company that cleared the way for the creation of the Public Utilities Commission, Clower has established himself as the champion of the consumer. He has maintained his effectiveness in the Senate this session by borrowing a trick from the lobby: He contacts every member of the Senate every day to check how they are leaning on key legislation. His aggressiveness, high media profile and the fact that he’s a double for television actor James Drury make him a natural to go on to higher office.

BEST SOLITAIRE PLAYER:

John Bryant, moderate Democrat, Dallas. Bryant is winning the Austin power game by breaking all the rules. A maverick reformer, he is near the top of Speaker Bill Clayton’s House enemies list. Bryant keeps his neck off the chopping block by a lot of hard work and a lot of blowing the whistle on the status quo. “I don’t have any problem with Clayton, “says the outspoken Bryant. “I just think he’s a bad Speaker. I want to see him replaced. ” One of the few urban representatives quick to fight for urban interests, Bryant is lying in wait until a legislative redistricting in the early 1980’s throws the balance of power in the House over to the urban members. “Right now,” he says, “my only ambition is to be around that long. ” He gets farther on guts than most of his colleagues do on connections.

PERCENTAGE PLAYERS:

Bob Maloney, moderate Republican, Highland Park. This three-term representative is described by one veteran of the legislative game as “probably the smartest man in the House of Representatives. ” Maloney, who got on Clayton’s bad side last summer during a special session rules fight, is not above joining forces with liberal Democrats when it meets his needs. Members of the capital press corps consider Maloney one of the “smoothest” in style. A veteran of the “filthy fifty” reformist faction, Maloney is considered to have tremendous political potential.

Other skillful gameplayers in the Dallas and Tarrant delegations are:

Lee Jackson, moderate Republican, Dallas, Jackson’s political instincts and connections with people like Gov. Clements will doubtless carry him a long way in the House, where he is widely respected for his ability to absorb pressure from both sides of an issue and then vote his convictions; Chris Semos, moderate Democrat, Dallas (chairman of the Dallas House delegation, he gets a long way on being dependable); Ray Keller, moderate Democrat, Duncanville (a freshman whose skill at the power game has taken him beyond the rookie category); Oscar Mauzy, liberal Democrat, Dallas (a seasoned master of Senate sleight-of-hand); Gib Lewis, moderate Democrat, Fort Worth (scores by being a Clayton team player); Bob McFarland, moderate Republican, Arlington; Frank Gaston, conservative Republican, Dallas; Bill Ceverha, conservative Republican, Richardson; Charles Evans, moderate Democrat, Hurst; Carlyle Smith, moderate Democrat, Grand Prairie; Fred Agnich, conservative Republican, Dallas; David Cain, moderate Democrat, Dallas.

PROMISING ROOKIES:

Reby Cary, liberal Democrat, Fort Worth.

Freshman legislators rarely get to first base in the legislative game, but Cary’s experience on the Fort Worth school board and the knowledge of the system he gained as a government pro-fessor at the University of Texas at Arlington have given him a head start. He is motivated by a desire to fill a vacuum; Fort Worth is without any effective black representation in Austin and Dallas is not in much better shape. Cary is an odds-on bet to become the Dallas-Fort Worth area’s most influential black spokesman in the legislature. Others who have advanced a few steps in this year’s session include Rep. Ted Lyon, moderate Democrat, Mesquite (works hard and learns fast); and Lanny Hall, moderate Democrat, Fort Worth (as a former aide to Congressman Jim Wright, Hall has a head start on learning to play the game.) There are also a few freshmen who haven’t particularly distinguished themselves, but haven’t embarrassed themselves too much, either. They include Representatives Anita Hill, moderate Democrat, Garland, and Bob Leonard, conservative Republican, Fort Worth.

WINNING A FEW, LOSING MORE:

Bill Braecklein, moderate Democrat, Dallas. Many in Austin might debate whether Braecklein was effective as a House member. There is no debate that he’s worthless as a Senator. The capital press corps sometimes debates about whether he has a pulse. He’s relatively quick to jump on the side of a lobby bill, but he seems to be mentally somewhere else during the rest of the Senate discussions. There may be a method to his nothingness. Braecklein’s District 16 is a strange mix, including parts of both Highland Park and Fair Park. It would be difficult not to offend some of his constituents every time he takes a stand. Braecklein has taken the easy way out, choosing simply to play dead.

Ike Harris, moderate Republican, Dallas.

Senator Harris does a good job of being a good ol’ boy, is one of the Senate’s premier party-goers, and knows how to anticipate and run with what the business lobby wants. Harris was picked as Governor Clements’ point man in that legislative body. Clements must feel disappointed by now. With all the enthusiasm of a wet dishrag, Harris carried a bill that would increase the governor’s budgetary power. When Harris’ colleagues shoved the bill down the Senator’s throat, he retreated in his characteristic sleepwalk fashion. Harris recently lent himself $22,600 from his campaign fund, explaining that he was so busy with the people’s work that he didn’t have time to earn money as an attorney. Harris has also carried some odious special interest bills, including a Southwest Airlines special which would have made it against the law for municipalities to appear before a regulatory body to oppose an application for an air route license. The bill made several Dallas city officials livid, and Harris quickly backed off. “There’s a good chance Ike just didn’t know that stipulation was in the bill,” said one capital veteran. “Harris has never been what you would call critical of the content of his proposals; in fact I doubt that he ever reads them. ” Despite his performance, Harris is nursing a delusion that he could run for lieutenant governor. The lobby owes him enough favors to provide a handsome war chest but it’s doubtful that the voters would have a big enough sense of humor to carry him past the primary. In addition to Braecklein and Harris, the area is currently under-represented by the following Representatives: Bill Blanton, conservative Republican, Farmers Branch; Paul Ragsdale, liberal Democrat, Dallas; Bob Ware, moderate Republican, Fort Worth; Bobby Webber, moderate Democrat, Fort Worth; Bill “Commander” Coody, moderate Democrat, Weatherford; Lanell Cofer, liberal Democrat, Dallas.

FLAKE:

Clay Smothers, conservative Democrat, Dallas, is not respected even by the House power faction he courts so hard. “Clay Smothers is trying to be the class clown, which is okay, ” says one capital veteran. “The pathetic thing about Smothers is that he is not even a good clown. He’s just a bad joke. ” When he backs an issue, its cause is weakened by his support. During a recent discussion of abortion, which he opposes, the depth of Smothers’ understanding of the subject was indicated when he asserted that “hysterectomies” are routinely performed on rape victims when they are treated at hospitals. Smothers, who frequently wears a blue jean leisure suit on the House floor, has been known to have the sergeant-at-arms throw reporters out for wearing blue jeans. The difference, he explained to the media, is “that mine are attractive. ” “He likes to pick on cripples, ” one Clayton lieutenant says. “Smothers likes to pick on people like the homosexuals and just grind them into the dirt just because he knows they are safe prey. He gets pleasure out of getting even. “

LESS THAN A FULL DECK:

Sam Hudson, liberal Democrat, Dallas. “Sam is really a sincere man, ” says one of Hudson’s fellow Dallas House members. “But unfortunately, Sam is a complete failure at managing money, time, and people.” Hudson proved that in the last legislative session when he outspent the other 149 House members on operating expenditures. Two sessions ago, Hudson was criticized because he literally did nothing, showing little interest in introducing legislation. Last session, he decided to show just how productive he could be, introducing more than 100 bills (many of which were meaningless) and going on a hunger strike until his peers passed at least some of them into law. The net result of more than two months of starvation was that Hudson got two of his bills passed, neither of which was controversial, and disappointed some of his critics by failing to starve himself into oblivion. He’s eating this time, but he’s taken all the bills he failed to pass two years ago back out of the legislative trash can and reintroduced them. “If you don’t watch Hudson, “says one House member, “he’ll introduce his telephone bill. ” Hudson is keenly attuned to the needs of his predominantly black district, and consistently supports legislation which would benefit that district. The tragedy is that when his constituents elected him, they elected a man who is so inept he can’t get anything accomplished for them.

Belly Andujar, conservative Republican, Fort Worth. Hands down, Sen. Andujar is the biggest waste of a Senate seat the Dallas-Fort Worth area has ever had the bad judgment to send to Austin. This session, one of her pet projects included pushing through the Senate a resolution to invite Abraham Lincoln to address the legislators. (A House member in a Lincoln costume was going to make the appearance.) Mrs. Andujar’s actions caused Lt. Gov. Bill Hobby to blow his stack. He called the Senate into closed session and lectured the Fort Worth senator. Didn’t the Senate realize, Hobby asked, what bozos the public already thought its lawmakers were? Hobby frequently has to tell Senator Andujar how to perform simple procedural tasks that any freshman should know, despite the fact she’s been in the Senate six years. “What’s really ironic,” says one capital veteran, “is that Betty ran a really hard and dirty re-election campaign. She fought like hell to keep that Senate seat, but she doesn’t know how to do anything with it now that she’s got it. “

Doyle Willis, moderate Democrat, Fort Worth.

Willis is living proof that practice does not make perfect. First elected to the House in 1947, Willis has been in and out of Austin for years, serving in the Senate and then returning to the House. He’s like an old fighter who’s been punched so many times he doesn’t really know how to find his corner when the bell rings. Willis has taken credit among his colleagues in the House for inventing a new campaign drive. When he is in his home district, he goes to funeral homes and signs the guest registration books at funerals of people he’s never even heard of. “The thing about that is, ” Willis has been quoted as saying, “that when Momma and Sister are looking over Daddy’s funeral book, they’ll see that name and say ’You know, I never realized Daddy was a friend of Doyle Willis.’ “

WHO’S FEEDING YOUR LEGISLATORS?

T

he Texas Legislature is not for sale; special interest groups bought and paid for it in the last election. The PAC’s, which are the fund-distributing arms of the various lobbies, gave incumbents thousands of dollars worth of campaign contributions last year. And although incumbents contend that a campaign contribution does not buy their affections, any lobbyist will tell you there is nothing like a few thousand bucks at campaign time to get a candidate’s attention. Here are a few of the Dallas/Fort Worth recipients of lobby largess:

Rep. Bob Davis of Irving. Two years ago, Davis was chairman of the House Committee on Insurance. During the campaign that preceded the legislative session, Davis received contributions from nearly three dozen special interest groups, including IMPACT (insurance agents), LUPAC (life underwriters), United Fidelity Life, American General Insurance, Southwestern Life, plus bankers, savings and loans, oil and gas interests, beer distributors, Lone Star Steel, dentists, realtors, chiropractors, home builders, and architects. During the 1978 campaign, he pulled in $17,615 in contributions, nearly half of it in donations of $300 or more from special interest groups.

Sen. Bill Meier, Euless. When Meier was facing a strong challenge for reelection last year, the special interests came to his aid. Meier’s major funding came from realtors, $10,000 in one shot; bankers, $2000; the “Good Government Fund of Fort Worth ” (primary contributor: oilman Perry Bass), $2000; architects, $1000; Good Government PAC of Fort Worth (executives of the Texas Electric Service Co.), $1000; employees of ENSERCH (parent company of Lone Star Gas), $500.

Rep. Gibson D. “Gib” Lewis (chairman of the Tarrant delegation). Re-districting threw Lewis into a tough fight and he needed a lot of financial help to win reelection. Lewis took money last year from beer and wine distributors, the savings and loan group, the real estate PA C ($3000 in two gifts), the doctors ($6000), ALCOA, the Texas Restaurant PAC, auto dealers, the Texas Energy PAC, Lone Star Steel of Dallas, dentists, and even $100 from Carco.

Sen. Ike Harris of Dallas. His 1976 election bid (the last time he ran) was financed by contributions from the Bankers Legislative League of Texas, ENSERCH, First International Bancshares Good Government Fund, the life insurance PAC, United Fidelity PAC, and several other special interest groups.

This year Harris disclosed that he’d received officeholder contributions from the psychotherapy PAC, beer and wine distributors, the life insurance PA C, and osteopaths.

Sen. Oscar Mauzy of Dallas.

Mauzy proved to be the best fund-raiser in the Dallas delegation, picking up more than $36,000 for his reelection campaign. A large portion came from First International Bancshares Good Government Fund, trial lawyers, the Texas AFL-CIO committee on political education, dentists, the Communication Workers of America committee on political education, the Texas Association of Life Underwriters, and several other groups.

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Local News

In a Friday Shakeup, 97.1 The Freak Changes Formats and Fires Radio Legend Mike Rhyner

Two reports indicate the demise of The Freak and it's free-flow talk format, and one of its most legendary voices confirmed he had been fired Friday.

Local News

Habitat For Humanity’s New CEO Is a Big Reason Why the Bond Included Housing Dollars

Ashley Brundage is leaving her longtime post at United Way to try and build more houses in more places. Let's hear how she's thinking about her new job.

By Matt Goodman

Sports News

Greg Bibb Pulls Back the Curtain on Dallas Wings Relocation From Arlington to Dallas

The Wings are set to receive $19 million in incentives over the next 15 years; additionally, Bibb expects the team to earn at least $1.5 million in additional ticket revenue per season thanks to the relocation.

By Ben Swanger