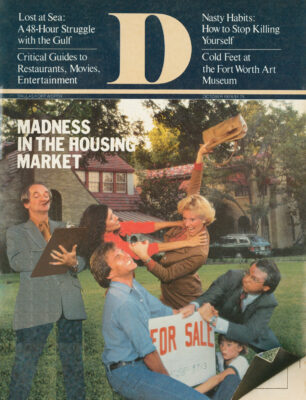

A characteristically Olympian observation from Sir Kenneth, but one that is applicable to the Fort Worth Art Museum, which is currently trying to recapture public support without losing its identity. Not long ago the rival of the Walker and the Whitney as America’s leading contemporary art museum, the FWAM has become a lonely and melancholy place, directorless and debt-ridden. It is virtually deserted even on weekends, when crowds are pouring into the nearby Kim-bell and Amon Carter. Except for “Stella Since 1970,” it has not had a distinguished show in over a year, and the fall schedule doesn’t look promising: a print exhibition drawn from the permanent collection, the Target collection of American photography, and a show composed of odds and ends from the DMFA’s permanent contemporary collection. The museum is now simply marking time.

“For several years we’ve had a serious cash flow problem,” says board president Richard Tucker, “and until that’s solved we won’t be originating or even buying any shows. Balancing the books has become our top priority.” The museum’s basic program, with its heavy emphasis on the performing arts, is extremely expensive. In the past the museum has also originated many shows – “The Great American Rodeo,” “Dan Flavin: Installations in Fluorescent Light,” “Los Angeles in the Seventies” – all of which required large initial investments that had to be recovered over a period of years from exhibition fees and catalogue sales. It has run the kind of high-powered program that would give even a wealthy museum the jitters.

And yet the basic question here isn’t simply money, but direction. It’s clear that the present board of trustees expects the museum to be run like a business and is prepared to take whatever steps are necessary to make that happen, including eliminating many of the programs that have brought national recognition. “We got plenty of attention,” says Tucker, “but we also paid a lot for it.” The new policy is strictly pay-as-you-go, and the overall goal is to make the museum more of a community institution. While this won’t mean découpage and exhibits of bluebonnet paintings, it may mean a shift to big crowd pleasers like the recent Calder show at the DMFA. Community service measured by head count.

Other people, including most of the staff, want the FWAM to remain a contemporary art museum – responsibly run, of course, but also one that continues to offer the kind of adventurous, experimental shows that the other museums in the area don’t. They point to the FWAM’s unique place among the city’s museums and argue that in trying to become less specialized it may succeed only in becoming a second-rate Kimbell or Amon Carter.

This is an important issue since, unlike its neighbors, the FWAM has practically no endowment. One third of its annual $500,000 operating budget comes from the city, the rest from grants, gifts, and fees. It has always been the poor museum in a rich museum town, and as government and foundation support for the arts has dwindled, its position has become shakier. Almost by definition, contemporary art is difficult, elusive, elitist. A Larry Bell sculpture is simply not as accessible as a Remington or a Rembrandt. Over the years the museum has been criticized for hanging too many tough shows that left the public puzzled about whether it was being educated or hoodwinked. Coun-, cilman Woodie Woods once remarked that if the museum put some of its art out on the sidewalk the city would pick it up. Everybody laughed at Woodie’s gaucherie. yet the FWAM has had trouble competing with the Kimbell and Carter and their familiar masterpieces.

Except when Henry Hopkins was the director. Hopkins had the talent for putting together high-quality, imaginative shows that the public was willing to support. He charmed and cajoled bankers, oilmen, and society matrons. Because of his stature in the art world he brought national attention to the work of Texas sculptors like George Green and James Surls. Most local artists talk about him in terms usually reserved for the Supreme Being. Even people who wouldn’t know Dan Flavin from Elmer Fudd admired Hopkins for putting the Fort Worth Art Museum on the map. When he was director there was no question about who ran the show.

Hopkins’s successors, Richard Koshalek and Jay Belloli, were not so fortunate, partly because they labored in the shadow of a legend, and partly because they had to live with the consequences of his expansion program. Before departing for San Francisco’s Museum of Art, Hopkins broke ground for a $1.3-million wing that more than doubled the FWAM’s exhibition space. Although the wing was needed, it also drained the museum’s resources so that when Richard Koshalek arrived from the Walker with plans for expanding the regular program to include theater, dance, and music, he found himself caught between rising costs and declining revenues. The people who had been willing to chip in a thousand or two for a sparkling new building forgot that it also takes money to run it year after year.

The deficit began to grow. Arrogant as well as brilliant, Koshalek made it clear that he wasn’t about to trim his program just to pay for the air conditioning. The museum’s job was to introduce new ideas and raise the public’s consciousness. That took a lot of money, and the city would have to get used to the fact.

Some members of the board, notably Charles Tandy, were delighted with Ko-shalek’s bravura, but others suspected that they had hired a lunatic who would outspend any budget. When Koshalek declared a $50,000 deficit his first year – the first in the museum’s history – suspicion turned to panic. Koshalek claims that he’s still not sure why he was fired, but others close to the situation say that his extravagant ways, coupled with very ambiguous signals from trustees about what they wanted the director to do, made the break inevitable: The trustees said that they wanted a bright, innovative director, then became upset when they couldn’t control him.

Their instructions to Jay Belloli, Ko-shalek’s successor, were more explicit: Get the budget in order! A quiet, scholarly man with none of his predecessor’s flamboyance, Belloli had no real desire to become director. He was young, inexperienced, and temperamentally unsuited for the kinds of public relations activities that go with the job. Still, he tried, to the point of saving paper clips and turning off rest-room lights, and in the end wound up with a deficit somewhere between $50,000 and $100,000 – much of it created by the very successful Stella show. Tired of budget hassles, he quit.

Now the trustees are again searching for a director, the fourth in ten years, and the fact that they are talking with people like Evan Turner, of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, indicates that they want an older, established museum person with a proven track record as both administrator and fund-raiser. They also apparently want someone who’ll stick around Fort Worth and not, as one board member put it, “just try to use this job as a steppingstone to New York.” Given the museum’s reputation for chopping off heads, it’s unlikely that the position will be filled quickly.

Obviously there’s nothing wrong with hiring a strong bottom-line person as director, provided that person isn’t simply a caretaker. Under Hopkins, Koshalek, and Belloli, the FWAM built a reputation as one of the most innovative institutions in the country. Even if it sometimes over-extended itself, especially under Koshalek, it never lacked courage or imagination. Given the present crisis, it is clear that cuts will have to be made; it’s the nature of the cuts that has people concerned.

If what the trustees really want is a director who will do safe, crowd-pleasing shows, then the situation is critical. The Fort Worth Art Museum is, after all, the contemporary art museum not only for Dallas-Fort Worth but for the entire Southwest. It has a role that the other museums in the area can’t fill. The DMFA is a general civic museum, the Carter and Kimbell together cover everything from cave painting to Picasso. Let them do the blockbusters; only the FWAM gives us a chance to see the work of Michael Asher and Robert Irwin. Its role is to be provocative and controversial, anything but safe.

If the local art community needs to have its mind bent occasionally, so do local artists. With the current chaos at the Contemporary Arts Museum in Houston and the generally dismal gallery situation locally, the Fort Worth Art Museum is practically the only outlet serious young artists in Texas have for their work. A vital, energetic contemporary art museum is the backbone of a healthy art community. Without it, artists are forced to work in a vacuum, finding their inspiration in back issues of Art Forum instead of from direct contact with the work of the best contemporary artists. Or else they leave town, a pattern followed with distressing regularity.

A revised program that included a few performance pieces, at least one avant-garde show, and maybe a Rauschenberg or a Johns retrospective could still be exciting. De Kooning might draw crowds, or Motherwell. The budget cuts needn’t be devastating. Yet how would the museum finance this kind of program? By broadening its base of support, for one thing. The current membership of the FWAM is approximately 1000, down from a high of 1300 just a few years ago. Even allowing for the limited appeal of contemporary art, this is a perilously small base. An aggressive, statewide membership drive is in order. At the same time the museum must work to get rid of its image as a private art club in which a few influential members make all the decisions and everyone else goes along for the ride.

Of course, if the members of the inner circle were all lavish supporters of the museum this might not be such a bad situation. But with a few exceptions, this isn’t the case. There are no Norton Simons or Margaret McDermotts on the board. Nearly every year the museum has had to request contributions from the city or its key supporters simply to cover operating expenses – hardly a healthy situation. One of the tasks facing the new director will be to get solid commitments from everyone on the board, not just a select few. If the trustees are as serious about having a contemporary art museum as they claim, then they have to be willing to support it. Otherwise, why would any first-rate director leave a secure job for a hand-to-mouth existence at an institution with a reputation for instability?

Which brings up the related question of whether, finally, this is a job for one person or two: a director responsible for programs and acquisitions and a development officer responsible for fund-raising. At the moment the trustees seem to be hoping for another triple-threat, Henry Hopkins type, but as most major museums in the country are discovering, a development officer can free the director to originate programs and attend to the permanent collection. He can actually run the museum instead of dividing his time between his office and an endless round of cocktail parties. The principal criticism of both Koshalek and Belloli was that they were imaginative directors and weak administrators. No one seems to have asked if, perhaps, they were spread too thin.

The next few months are going to becritical for the Fort Worth Art Museum.In the past nobody had to remind it of itsresponsibilities. It regularly brought thebest contemporary art to the area andconsistently challenged its audiences instead of patronizing them. With all thecurrent talk about cash flow and balancedbudgets, there’s a danger of forgettingpast achievements. All suggestions thatthe museum quietly pull back and playfollow the leader should be greeted with aresounding No!

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Local News

In a Friday Shakeup, 97.1 The Freak Changes Formats and Fires Radio Legend Mike Rhyner

Two reports indicate the demise of The Freak and it's free-flow talk format, and one of its most legendary voices confirmed he had been fired Friday.

Local News

Habitat For Humanity’s New CEO Is a Big Reason Why the Bond Included Housing Dollars

Ashley Brundage is leaving her longtime post at United Way to try and build more houses in more places. Let's hear how she's thinking about her new job.

By Matt Goodman

Sports News

Greg Bibb Pulls Back the Curtain on Dallas Wings Relocation From Arlington to Dallas

The Wings are set to receive $19 million in incentives over the next 15 years; additionally, Bibb expects the team to earn at least $1.5 million in additional ticket revenue per season thanks to the relocation.

By Ben Swanger