It s close to midnight on a Sunday in late May; The Graduate, with Dustin Hoffman and Katherine Ross, is once again reeling its way over the Channel 8 airwaves and into living rooms all over Dallas, including mine. This being the 19th time I’ve seen i,t, I watch knowingly as Benjamin Braddock leads Elaine Robinson into the striptease joint. Okay, my memory tells me, here’s where Benjamin sits at a table in front of the stage and gazes through his sunglasses at the stripper; and here’s where Elaine stares into her lap; and here’s where the stripper unveils her chest and walks toward Elaine; and here’s where the Channel 8 editing crew protects us from watching the stripper twirl the tassels on her breasts. But no-there they are, tassels, breasts, the whole works, twirling away. I’m shocked. Not by naked breasts, but by naked breasts on Channel 8. Mike Shapiro, where are you?

The name Mike Shapiro once meant absolutely nothing to television watchers. Then, on a June afternoon in 1961, Mike Shapiro, general manager of WFAA-TV Channel 8, strode into one of the station’s studios. His stride, however, did not carry its usual self-confidence. Mike Shapiro was scared to death. Though he’d been in the broadcasting business for 15 years, this was to be his first venture in front of the cameras.

He sat down in the swivel chair behind the large desk which dominated the set. fidgeted with a few notes and letters scattered in front of him, nervously extinguished his cigarette, and waited.The cameras rolled and Mike Shapiro sputtered a welcome to viewers of his new show, “Let Me Speak To The Manager.” He opened the show by reading a letter from a woman who was incensed that her favorite show, “One Step Beyond,” had been interrupted four weeks in a row by staff meteorologist Warren Culbertson’s reports of approaching rainstorms, as revealed by the station’s brand-new radar system. Shapiro then offered his explanation, liberally punctuated with “uhs” and “ers,” defending the interruptions. Fifteen minutes later. Shapiro closed the show with an appeal to viewers for letters about television-queries, complaints, compliments, whatever.

When the cameras were off and the lights were down, Mike Shapiro leaned back in the swivel chair and thought to himself, “This show will never make it. I’ll never get enough letters.” Seventeen years and 70,000 letters later, Mike Shapiro is still at it.

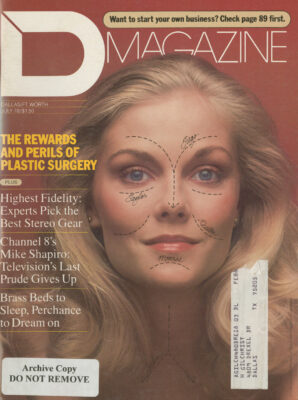

Seventeen televised years and 70,000 letters have made a celebrity of Mike Shapiro. Given that Dallas is less than a mecca for TV stars, Shapiro can be considered a veritable giant of the local screen. But Shapiro’s notoriety derives less from his presence on television than from what he has kept off television. During those 17 years-first as station manager, then as general manager, and now as president of Belo Broadcasting (Channel 8’s corporate overlord)-Mike Shapiro has waged a dutiful war against the lewd and the rude on TV. There was a time when those tassels would never have twirled on Mike Shapiro’s station. Why, i wonder, are they twirling now.?

While I’m sitting in his spacious office, admiring its comforts, waiting for Mike Shapiro to arrive, my expectations are settled. We’ve never met, never even spoken (his secretary has arranged the appointment), but I’ve watched him on television, and I know what I’ll see. He’ll walk in, small and dumpy, wearing a tie, a buttoned sport coat, and his oversized black hornrimmed glasses. He’ll sit down in the swivel chair behind his desk, smile at me, and, in his slightly annoying nasal voice, say, “Hello. What can I do for you?”

Mike Shapiro walks into his office. No, he blows into his office. And he’s big. He’s wearing those horn-rimmed glasses, but they’re not oversized, he is. His short-sleeved cotton dress shirt tugs at his shoulders as he marches toward me. He’s wearing a tie, but the knot dangles loosely at the throat. He extends a strong hand and, before sitting, looks down at me dourly. In a gruff voice, he says, “Okay, what’s this all about?” I’m taken aback: What happened to that nice little man on television? But when Shapiro sits down in his swivel chair behind his desk, I’m reassured. This chair, like the one on the set for his television show, is high-backed, rising above his shoulders, making him look much smaller.

“I don’t want this story to come off with me having a halo over my head,” says Mike Shapiro as he lights up a Kool. “I’m really not a do-gooder. It bothers me more than anything when someone says to me, ’Hey Shapiro, do you think you walk on water?’ I don’t want to be put in the position of playing God. But I do have a responsibility to our viewers.”

The image of Saint Mike, moral guardian of the airwaves, is a tough one to shake. But as he rises from his desk, relocates more comfortably on his office couch, puffs on his Kool, and talks amiably about his career, he betrays no piety.

Mike Shapiro never intended to be a television personality. He never even intended to be a broadcaster. He wanted to be an airplane pilot. But in 1945, as a grounded Air Corps pilot laid up in a Fort Collins, Colorado, hospital recovering from his 14th bout with chronic malaria, Shapiro was told that the hospital’s communication system, a kind of internal radio station, was looking for someone to spin a few records and read a little news. Seeking relief from boredom, Shapiro volunteered.

Over the next few years, finding himself “not qualified for anything else,” Shapiro kicked around the radio boondocks from his home in Duluth, Minnesota, to his wife’s home in Brownwood, Texas. In 1952 he joined a firm selling advertising novelties – calendars, lighters, playing cards. While on a sales call to WFAA in Dallas, he was confronted by a station manager who looked at Shapiro and said, “What are you doing selling pencils? Get into television.” So he did.

“I was fortunate enough,” says Shapiro in a phrase he often uses, “to have gotten into television at the perfect time. There were no experts in television when I got in. Nobody had any experience. That as much as anything is the reason for my success. I’ve been here from day one.” He started with WFAA as a salesman. Only six years later, he was made station manager of WFAA-TV, and two years later, in 1960, he became general manager of WFAA Radio and Television.

If Shapiro’s career to that point was almost accidental and hastened by the propulsive growth of a new industry, his career since has been purely self-deter-mined. In 1961, he listened to FCC chairman Newton Minow proclaim television “a vast wasteland.” Shapiro was stung by this condemnation of his beloved industry and decided to do some rectifying of his own. Spurred by the letters of complaint about the weather bulletins, he decided to try a kind of “letters-to-the-ed-itor” show. “Let Me Speak To The Manager” (the title was Shapiro’s) was well-received, but it might never have achieved lasting success had it not been for an incident, early in that first season, which pushed Mike Shapiro into the local limelight. ABC proposed to air an episode of the series “Bus Stop,” with singer Fabian cast as a psychotic killer. Shapiro, after previewing the episode, decided to yank it off the air, as did several other ABC affiliates around the country. (I think, ” Shapiro says now, “the show had a homosexual in it, and a murder in it . . . . I forget what the problem was.”) The censorship was widely publicized, and on his show Shapiro explained his decision, citing violations of the NAB Code. During the next week, Shapiro was swamped with more than a thousand letters, pro and con. “Let Me Speak To The Manager” was a hometown hit, and Mike Shapiro was tabbed as a video crusader.

Shapiro doesn’t see himself as a crusader, or even as a censor. He rejects the halo. As far as he’s concerned, he’s just doing his job. “As a licensee of this station,” he says, “I am, by contract, responsible for what is aired. Network television is created in New York and Los Angeles. The moral climate of Manhattan and Hollywood does not necessarily fit that of Middle America. A local station is in an untenable position if its audience is offended by the network. As the licensee, I’m responsible for seeing that they’re not offended.”

Shapiro has often fulfilled that obligation. But while his own professional code has not changed over the years, his methods of enforcement have. In 1961, with “Bus Stop,” the method was removal from the airwaves. After taking several years of flak for his surgery on the Channel 8 schedule, however, Shapiro adopted a less drastic technique: relocation of a questionable show to a less-watched (usually late-night) time slot. After NBC successfully launched “Laugh-In” in 1968, ABC concocted a similar (though inferior) series called “Turn On,” and scheduled it for Wednesday night in prime time. Shapiro previewed the show, pronounced it “garbage,” and moved it to 10:30 Sunday night. “The public reaction,” recalls Shapiro, “was furious. ’How dare you?’ everyone screamed. Then they all watched it on Sunday night and wrote me and said, ’That was garbage. If you had any taste you wouldn’t have shown it at all.’ “

The rescheduling technique assuaged some critics for a while, but when Shapiro applied it to ABC’s prime time airing of the controversial but critically acclaimed movie The L-ShapedRoom, the outcry from viewers reached new heights. Shortly thereafter, Shapiro adopted a new method of sanitation: the disclaimer, a pre-show warning of unsuitable material. Shapiro used this device five years before the networks made disclaimers commonplace. “But the disclaimer,” Shapiro sighs, “is not entirely satisfactory. These days you put a disclaimer before a movie and you’ll have every 10-year-old kid in the Metroplex in front of his TV set.”

The gradual erosion of Shapiro’s power as a censor is ironic, really. Shapiro, at age 59. has ascended to the upper echelons of his profession. As president and one of three trustees of the highly successful Belo Broadcasting Corp., he exercises control over WFAA-TV-Channel 8, WFAA-AM radio, KZEW-FM radio, and KFDM-TV-Channel 6, the CBS-affiliate in Beaumont. He carries a very strong reputation in the broadcasting industry nationally, having served in a number of prestigious posts, including chairman of the TV Board of Directors of the National Association of Broadcasters. Yet despite the prominence, despite the power, despite the credentials, Shapiro has lost some of his moral authority – because the medium’s power has grown more swiftly than his own. Television’s snowballing social force has flattened the ethical fences that Mike Shapiro the station manager was once able to erect. His own Channel 8 is now riddled with the satirical sex of “SOAP,” the flouncy sex of “Three’s Company,” the hygienic sex of feminine spray commercials – and The Graduate’s once-forbidden twirling tassels.

“Well,” Shapiro sighs, “The Graduate was preceded by a disclaimer and was shown in a late time slot. I have to think that was sufficient now. Times change. People aren’t as easily shocked any more. And television has done it. But I don’t say that’s right and I don’t say that’s wrong.”

Despite 17 years of practicing his electronic ethic, Mike Shapiro is not at all sure what that ethic is. It’s a curious paradox: The man who has drawn distinctive moral lines in front of hundreds of thousands of viewers a week cannot easily define those lines in the privacy of his office. He shifts restlessly on the couch during the conversation – sitting forward, leaning back, sometimes standing, sometimes wandering to his desk, betraying boundless energy. It is physical energy that perhaps does not lend itself to abstract discussion. He is a talker, but not an incisive talker. Yet one suspects that, when he acts, he acts decisively. To axe a show comes easily to him; to articulate the reasons why does not.

“I’m a man of mixed emotions,” he says, after finally settling into a cor ner of the couch with one leg extended along its length, a pose as close to contented as he gets. “At times, I’m totally mixed up. Sometimes I find myself saying, ’Mike, you’re a hypocrite.’ For me to see a show as wrong, to say it’s wrong, and then not cancel it is hypocritical. But on the other hand, I don’t want to be a dictator. If I used to be an arbiter of taste, or whatever you want to call it, now I’m just an interlocutor, a middleman between the network and the audience. These days, when I express my disagreements with network programming, the reaction I get from the network is ’If these shows are so bad, why are they so popular?” How can I counter that? Whenever I buck, whenever I go against the masses, eight times out of ten I’m just going on my gut reactions in terms of responsibility. I’ll bend to the community desire and put something on the air. but I’ll give my opinion first.” And he will. His authority may have waned, but his distress has not.

“Many are convinced that television is breaking up the moral fiber of this country. I don’t think that television has created the new morality, but television’s portrayal of the new morality has made it acceptable. Television has endorsed it, and in so doing has made a mockery of marriage, family, the church, all the things that used to mold us. Maybe we were wrong. I don’t know. That’s not my point. My point is that any subject can be approached – it’s the level of taste and discretion that disturbs me. All three networks are guilty of inserting sex and violence for pure sensationalist value, to give them something to promote, to assure a box-office rating before it’s even aired.”

Perhaps what that means is that Mike Shapiro, contrary to popular belief, is not nearly so concerned with the state of American morality as he is with the state of American television. Morality is no more his concern than anyone else’s; television is. When he says, “Television is the most powerful industry ever devised by man.” he exudes both love and fear. Mike Shapiro cares about television. He doesn’t care about nudity; he cares about nudity on television. He cares, it seems about everything on television.

“Broadcasting has been damn good to me. And I don’t want to bite the hand that feeds me. But in 30 years of television, I’ve never seen so much chaos. The industry is full of abuses. I’m very concerned today about overcommercializa-tion. It’s my contention that our medium is very underpriced – we can derive the same amount of programming with fewer commercials at higher rates. The sheer number of commercials on television now is an insult to the viewing public. One of my biggest disappointments [as a member of the board of directors of the TV Code Authority of the NAB] has been the advent of personal hygiene product advertising. Since Preparation H broke the ban, it’s been a deluge. The code has been changed to allow such products if they’re presented in good taste. Well, I think a feminine hygiene product in the living room at dinner time can be offensive as a product, no matter how tastefully it’s done. The normal amount of commercial time on network television is 18 minutes per hour. For the Ali-Spinks fight coming up in September, ABC wants to run 23 minutes per hour. It has to stop somewhere.”

Shapiro’s displeasure with television advertising is not idle censure. He has, over the years, jousted almost as aggressively with issues of advertising as he has with issues of programming. He has often refused to run ads on the grounds of tastelessness. He shows particular disdain for sensational movie trailers, but he has also pulled the plug on a furniture store commercial. He annually conducts a poll of his viewers to determine their favorite and least favorite commercials, the results of which he exposes on his show; some of the least favorites have indicated more than a little irritation at being so named. Shapiro also has seen ad contracts canceled by advertisers (car dealers, supermarket chains) after his news staff aired investigative stories on them. All have been individual battles; but what disturbs him most is the increasing influence advertising has over the medium in general.

“Advertisers have begun to dictate programming. They look at shows that are winners and say ’Give me that.’ If a show catches on with one network, the others will copy it. The result is a disturbing sameness. Creativity has been seriously reduced. It’s frustrating that we don’t attempt more. Overnight ratings have made it impossible for new and different shows to have time to create an audience. The ratings are ruling everything. It’s especially frustrating because we can do better – but the public isn’t interested. We do public service and the viewers change the channel. We’ve discussed force-feeding where, for example, all stations would air public service presentations simultaneously from, say, nine o’clock to ten o’clock. But then people would just turn their sets off. People cite the success of 60 Minutes, but that show has simply found a time slot and won by default. You think it would survive against ’Happy Days?’ No way.”

Shapiro lights up another Kool and seeks relief from his exasperation. He finds it in the future. “Twenty years from now,” he says, “the technology of the industry will have changed everything. Satellite, home video, all the advancements will offer any major market a hundred different program sources, rather than the three all-powerful networks we have now. The networks will follow the path of network radio, which is now basically a dispenser of news. The television networks will simply become program carriers and local stations will buy from them. Locally there will be a sports station, a weather station, a shopping station, a movie station, a dirty movie station – the variety of choices alone will return censorship to the viewer. When that becomes a reality, there will be no reason for anyone to complain about what they see on TV.”

In the meantime, though, people will continue to complain. And Mike Shapiro will continue to listen to them. “It’s a horrible mistake for our industry to ignore honest viewer unhappiness. It comes back to the idea of responsibility to your own particular regional audience. Unfortunately. I have no practical way of testing their pulse. Except for my show. That’s why I do it.”

“Let Me Speak To The Manager” has, over the course of 17 years, been through some changes. (The name, for one; the show was retitled “Inside Television” a few years ago when Shapiro became president instead of a mere manager.) Shapiro has tried several format variations. He tried a studio audience but found it to be unmanageable. He tried phone-in questions until one guy called to find out how he could get invited on to ’The Dating Game” and tied up the line for seven minutes. He tried a live show, but abandoned that effort on the first attempt, when Howard Cosell (a friend of Shapiro’s) made a surprise appearance and said, “Hey, Shapiro, just what is this Mickey Mouse show you’re doing here?” The “Show Biz Quiz” was a long-time fixture but it was finally discarded. (Shapiro was convinced of the quiz’s popularity, but he had to question its integrity when, after he misidentified Dale Evans” horse as Buttercup, instead of Buttermilk, he got one of his largest mail responses ever. His decision to kill the quiz may also have had something to do with the guy who called him at home late at night from a bar, waking Shapiro up to ask if Goofy was a dog or a horse.) He has also removed the second character from the show, the “interviewer” who sat with his back to the camera and read Shapiro the readers’ questions. He’s tried interviewing celebrities on the show, but finally determined that “the viewers don’t want to see me interviewing, they want to see me in trouble.” Shapiro now goes it alone.

He’s not through experimenting, however. This fall he plans to go to shopping centers and other public places, offering himself up for some face-to-face abuse via minicam. Is it masochistic? “I really don’t enjoy the flak, but it’s really my only opportunity to gauge our audience. I realize that it doesn’t present a true cross section. The notion that people usually write when they’re unhappy, not when they’re happy, is probably true. So you don’t necessarily get balance between pro and con, liberal and conservative. But over time, I think we’ve been able to reach all elements. And I enjoy being able to tell the public what’s happening in the television industry. Besides, I’ve got as much ham in me as the next guy.”

It’s odd that Mike Shapiro’s public persona is shaped so thoroughly by his role on “Inside Television.” He provides an easy target. Even after 17 years, he’s not exactly smooth up there in thatswivel chair; his stage presence is lessthan majestic, and his delivery is lessthan polished, though it’s almost a refreshing kind of ineptitude. (Shapirodoesn’t try to defend himself: “Yeah, Iknow. I sound like Andy Devine withlung trouble.”) Much of his mail is borderline crank, and the “issues” can betedious (he himself admits to growing”sick and tired of answering questionsabout sex and violence, sex and violence, sex and violence”). To judgehim by his show, it would be easy tosee Mike Shapiro as a well-meaning,somewhat prudish klutz. But his television personality has little to do with hisreal job or his real success. “1 don’t getpaid a dime for “Inside Television,” hesays. “My number one responsibility isto run a successful group of broadcaststations. My greatest value is in findingquality people to work here. And mygreatest satisfaction is the position thisstation enjoys in this community. We’veestablished ourselves as a station thatreally cares.”

The success of Belo Broadcasting under Shapiro has been remarkable. The on-screen klutz is a behind-the-scenes wizard. KFDM-TV in Beaumont is the top station in the market. KZEW-FM (“The Zoo”) has established itself as one of the top rock stations in northeast Texas. WFAA-AM, after some recent difficulties, appears to be finding its groove in the news-talk format. And WFAA-TV. Channel 8 – the flagship of the fleet – has gathered all kinds of laurels. WFAA has long been considered by ABC to be one of its top affiliates. In the dog days of ABC, Channel 8 scored better ratings than the network as a whole. (Shapiro himself was offered a vice-presidency with ABC several years ago, but he declined, wary of the heavy pressure: “I was afraid in five years I might be dead.”) In recent years, Channel 8’s local news, the most significant barometer of a station’s achievement, has received numerous accolades for its reportage and technical sophistication. In a recent study by the FCC for the year of 1977, WFAA-TV ranked third in the nation in terms of share of time devoted to local news and public affairs programming. In every case, the success can be traced to top-flight managers, carefully gathered and loosely governed by Shapiro. “Mike Shapiro,” says one long-time associate, “creates an ambience of responsibility.”

The personal successes have hardly made Mike Shapiro complacent. On the contrary, he’s probably more dissatisfied with his industry than he’s ever been. He readily admits that the monster that is television is running away from him. “My objectives are the same, but my opportunities are not as great. Over the years, the networks have taken over and programmed more time than ever. They’ve assumed an awesome responsibility, which they’ve often abused. And it’s placed local stations in a much more critical and uncontrollable position.”

Mike Shapiro shakes his head as he rises from his couch, perplexed perhaps by the thought that the president of a major broadcasting corporation can do little about modern television. Because if he can’t, who can?

“Well,” he says, “I’ve still got my show. And I’ve been trying to tell the audiences that they’re the ones to make the decisions now. Not me. The public is the best critic in the world. And if there’s enough of a ground swell of dissatisfaction, it will eventually get to the networks. And television can be improved. But if the audience keeps watching, if they keep buying what the networks put out, it’s not going to change.”

Like others of Mike Shapiro’s old-time values, this idealistic image of viewer democracy is a little hard to swallow. Perhaps it’s wishful thinking on his part, a hope that the public will somehow rise up and reshape television in the image of responsibility that he has cast for it. Because he knows that while you can still speak to the manager, and while he is still glad to listen, he can’t guarantee results. But he can keep trying.

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Government & Law

The Lawyer Who Landlords Don’t Want to See in Court

Attorney Mark Melton started helping people on Facebook during the pandemic. Before he knew it, he’d assembled the country’s only group of lawyers focused full time on stopping illegal evictions—and saving taxpayers millions.

By Matt Goodman

Home & Garden

Kitchen Confidential—The Return of the Scullery

The scullery is seeing a resurgence, allowing hosts and home chefs to put their best foot forward—and keep messes behind closed doors.

By Lydia Brooks