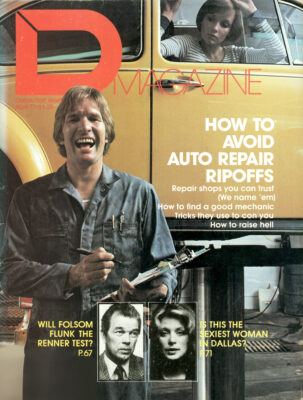

It’s hard to believe that the little town of Renner, perhaps best known for its Preston Road massage parlor-trailers, could teach Bob Folsom so much about being Mayor of Dallas. Just over a year ago land baron Folsom was quietly developing his 1,500-acre Bent Tree project, a far North Dallas conglomeration of homes, shopping areas and office developments, plus the swank Bent Tree Country Club. Folsom was well on his way to wheeling and dealing with officials from Dallas and Renner, two cities encompassing Bent Tree. Last year Folsom decided that he also wanted to be Mayor of Dallas, which is considerably different from being a free-wheeling developer. The two hats don’t fit neatly one on top of the other, and the mayor is learning there are times when he canwear one or the other, butfew occasions when he can wearboth.

It is obvious that Bob Folsom is grasping the point, though assuredly he is biting his tongue to prove it. Recently he talked in his office about the Renner consolidation issue,conducting himself like a model of restraint. Folsom had just been skewered in a front page Dallas Morning News story which went to extraordinary lengths to demonstrate that Folsom has much to gain if Dallas takes in Renner. (In fact, the same things that he has to gain if any other city takes in Renner – land sales, higher city taxes and competi tion from other developers.) After spending 20 minutes defending himself from the News’ assault, Folsom is asked the perfunctory question. Does the mayor think he was treated fairly by the Dallas Morning News?

“Is this on the record or off the record?” he asks.

On the record.

“Then I have no comment” he says, smiling politely.

The mayor has ma a few comments. The first ones came in telephone calls to the News’ management before the story was printed, and the rest came after publication, including a personal meeting with the newspaper’s hierarchy. But Bob Folsom has learned his lesson, so well in fact that he can’t even be bullied into defending himself publicly.

He listens to the next question. “There are some people who know that you paid about $15,000 an acre for most of that Bent Tree land and that you’re selling it for prices ranging over $100,000 an acre. Would you like to talk about what your costs are besides buying the land?” With some prodding, Folsom points out that he has to pay interest on the loan which financed the purchase, city and school taxes, plus all of the cost of development -engineering studies, water lines, streets, sewers, and so on. In other words, the mayor is not making $90,000 an acre in Renner land.

“Could you relate all of those costs to a single acre of land so people can see how much it cost to put in a development like Bent Tree?” is the next question.

“No,” he says. “The average guy wouldn’t understand that.”

What the average guy does understand, as does Folsom, is that the mayor has worked himself into a corner, which he is willing to stay in until the Renner issue is settled. He and many other civic leaders are damned if they do fight for Rennercon-solidation and damned if they don’t. They’d love to because it’s so needed but they don’t dare, because the Renner issue is particularly vulnerable to the “fat cat charge” – that the main reason Dallas leadership wants to take in Renner is that half of the downtown fat cats own land out there.

Mayor Folsom got the whole mess started on his own, by failing to realize that as land baron he could operate one way, but as mayor he must handle business differently. His major mistake was meeting privately last summer with Renner Mayor Ronald Hartline, to discuss whether Dallas would be willing to supply Renner with water. Hartline came to beg. Folsom came to bargain.

Hartline needed water for his citizens, many of whom had spent their summer evenings without enough well water to flush the toilets. Folsom said Dallas might be willing to sell water to Renner, but not without a piece of Renner’s hide in return, specifically the entire western half of Renner’s 5,800 acres. Hartline countered by suggesting Renner might be willing to surrender its Denton County acreage, perhaps one-fifth of the city. Folsom said he didn’t think that would be offering enough, and that Hartline should negotiate further with Dallas city manager George Schrader, who later would demand about two-thirds of Renner.

Folsom made two mistakes. First he bargained to bring into Dallas an area of Renner in which he owned perhaps one-quarter of the land. The net effect of this is that several hundred acres of his land would be assured of receiving water and sewers from Dallas, something which Renner is unable to provide. To be sure, Folsom as developer would pay for most of the water and sewer lines, but at least the service would be available, hastening the day when he could sell off his land.

Folsom’s other error was choosing to meet privately with Hartline at Fol-som’s own country club, Bent Tree, to discuss city business, not just ordinary city business, but an issue in which he had a stake. Whether the mayor has fully grasped these points isn’t clear.

“It wasn’t a private meeting,” Folsom protests. “We walked all over Bent Tree Country Club before lunch – anybody there could have seen us. Only after lunch did we go into a private meeting room.” Folsom says he now realizes that he erred by meeting with the Renner mayor to discuss an issue in which he was involved financially, but that “if the mayor of Richardson telephoned me tomorrow and wanted to have a private lunch to discuss city business, I wouldn’t hesitate to meet with him.”

Folsom’s actions have endangered a cause with considerable merit, one that otherwise might have passed easily. The Dallas Chamber of Commerce and the Dallas Citizens Council will be pushing for April 2 voter approval of Renner consolidation, but it won’t be easy. Citizens Council member Morris Hite, chairman of Tracy-Locke Advertising, is well aware of the problem, especially since he is heading a committee to push for Renner consolidation. “In retrospect Bobby made a mistake by taking an advocacy position on Renner,” Hite says. “He laid himself open to conflict of interest charges. Everybody’s a little spooked on the Renner issue because they’re afraid if they speak up they’ll be charged with some conflict of interest. At least I don’t own any land there so I can speak up.”

Turning the Renner consolidation vote into a fat cat issue would be easy enough, because indeed many Renner landholders are Dallas’ wealthiest citizens. The largest is the McKamy family, which has owned Renner land for generations, and couldn’t be considered speculators, because the family’s ownership dates back to the 19th century. Folsom is the second largest Renner landowner, followed by developer Ray Hunt, oilman Paul Pewitt and the Haggar family, of Haggar slacks. John Murchi-son owns quite a bit of Renner land as does Trammell Crow, who also owns even more land contiguous to Renner, which would be annexed if Dallas absorbs Renner.

Some of this land clearly was bought on speculation, however it now appears that the potential profits to be made if Loop 9 had passed through the area, as once was projected, have disappeared. Loop 9 is practically a dead issue, because of a shortage of state highway funds. Several landowners who bought their acreage based on that speculation now want out, and if Dallas does absorb Renner, then their chances of getting out soon are much increased. An example is Ray Hunt, who in 1972 bought 327 acres of Renner land “for investment purposes.” Today Hunt has a buyer with an option to purchase the 327 acres in northeast Renner. That option expires in June, and it’s likely that the potential buyer will take careful note of whether Renner consolidates with Dallas before exercising his option to buy.

The major opposition to Renner consolidation comes from one Dallas City Council member, Juanita Craft, and the Citizens for Representative Government (CRG). Mrs. Craft’s position is that Dallas should spend money first on the inner city, which has its own problems, and then worry about spending money on northward expansion. Countering her argument is a group of projections provided by the Dallas city manager’s office, which believes that from the beginning more tax money will flow out of Renner than will flow in. The projections show 1977-78 tax revenues from Renner, if it joins Dallas, of $470,000, while only 338,000 tax dollars will go into Renner. More than half of that is capital improvements, such as upgrading existing streets and replacing bridges, costs which should drop off sharply after three years. Although Renner’s present tax base is only $450 million, city manager George Schrader estimates that in 20 years it will be $900 million, gener-ating $10 million in taxes each year.

“We’re going to talk to Mrs. Craft,” says Hite, “and explain to her that if the inner city had to support itself on its own tax base, it would be in bad shape. We’ve got to have these expensive developments in outlying areas to support the inner city areas which don’t generate very much property taxes,” Hite adds. “Gads, if we’re going to keep on supporting the inner city we’ve got to take in new areas.”

Opposition from the CRG is more tangled. Spokesman Don Fielding outlines a series of complaints. Perhaps the most significant one is that Dallas expansion to the north, he thinks, is really a ruse by the Dallas leadership to open a haven for Dallasites seeking to avoid the Dallas Independent School District and busing. “I think they are being less than candid about this,” he says.

“We can’t go on expanding forever,” Fielding adds. “Where is all of this going to stop? The Red River? People don’t want to live in a city the size of New York. That’s why they live in Dallas.” The CRG also suggests that the development of Renner and expansion of its tax base will take many years to grow to the proportions which proponents suggest. “We also need to consider the cost of municipal services,” he says, “because the farther out we expand the more they cost us. We need to be spending our money redeveloping the inner city, not spreading out all over the place.”

Fielding takes Folsom to task for speaking at a gathering of Renner citizens last summer, at which Folsom outlined what Dallas wanted before the city would supply water to Renner. “Who was the mayor to make a deal with Renner?” asks Fielding. “There was no council resolution authorizing him to do so. He has no power to make deals for Dallas. And I think the mayor has been less than candid with us about his role in the Renner issue,” Fielding continues. “Everyone knows that if Renner becomes part of Dallas it will greatly enhance the value of his land.”

At the moment Renner doesn’t look like much of a prize. It has three pockets of homes in its 5,800 acres, covering a small portion of its mostly undeveloped territory. Few of the streets are paved, sewage is handled by septic tanks and water comes from three wells and its quality is questionable. In many ways the town was passed up by the 20th century. Even though it was founded in 1888 when the Cotton Belt tracks were laid down, Renner today has a population of only 500 or 600 residents. High-priced housing developments are closing in on it from three sides – Dallas from the south, Carrollton from the west, and Piano from the east. The only thing keeping Renner from blossoming into similar developments is the water problem.

The only way Renner seems able to buy the water is to buy it from Dallas, as do most of the northern suburbs. But the Dallas City Council adopted a resolution banning further sales of water to the suburbs until a price battle is settled. About two months ago Renner residents, perhaps thinking about another summer with severe water shortages, voted two-to-one to offer their town to Dallas. If Dallas voters turn down Renner, then it is possible that another suburb, probably Addison or Carroll-ton, will take in Renner and reap its projected tax base.

“We’re paying for a lack of vision shown by our earlier city councils,” says Hite, “which had a limited expansion policy. We’ve got to get aggressive and take in more land.” In 1960, for instance, 36 percent of the City of Dallas was undeveloped. Today that percentage is 20 percent. Renner consolidation would raise the total to 23 percent.

Although Renner consolidation is the immediate issue, the most interesting horse race is occurring north of Renner, where Carrollton and Piano are streaking across the prairie, annexing enough land to seal off Dallas. Already Carrollton and Piano have annexed (or reserved for annexation) everything immediately north of Dallas but Renner and the tiny town of Hebron. If Dallas takes in Renner, then there is a chance Dallas could eventually consolidate with Hebron, perhaps giving Dallas a “door to the north.” Many observers think Hebron will become another Renner, forced to consolidate with another city, in this case either Carrollton or Dallas. Judging by Carrollton’s recent annexations, it appears Carrollton is thinking a lot about Hebron these days, and if Dallas is ever to have a shot at wooing Hebron, it must first take in Renner. One city cannot leap over another to annex land – it must continue on a contiguous path, and for Dallas that path must include Renner followed by Hebron.

This too is a sensitive issue to the Dallas leadership, which fears the Hebron question will stir up those who think that allowing growth to the north will somehow sap the city’s energy away from other areas.

At a time when the Mayor of Dallas normally would be out leading the charge for Renner consolidation, Folsom is keeping a low profile, hoping not to stir up the voters. About the most he will say is that “You can bet we will make a bundle on Bent Tree, no matter what city it winds up in, because we took some big risks out there.” By “big risks” Folsom means that he personally signed many of the notes financing development of the area, which is obvious when one looks at a financial report Folsom filed last summer with the city. The report shows that Folsom has signed eight unsecured notes, each in excess of $10,000. A State of Texas report lists him on 22 other notes – all secured by his various properties, including Bent Tree.

The Citizens Council and Hite aresomewhat worried about passage of theRenner issue. “Had this been on theballot by itself, like a bond issue,” Hitesays, “it would easily pass, becauseNorth Dallas understands these thingsand furnishes 75 percent of the vote.But if we can get the facts out to NorthDallas, I still think we can win,” hesays. “After all, when two people asdiverse as Adlene Harrison and JohnLeedom support one issue, then it’s gotto have some merit.”

Renner: Why Dallas Needs It, and Who Owns It

Understanding the strategic importance of Renner is very difficult without a map, so we’ve prepared one with the latest city limits of the six cities involved in the Renner scramble – Piano, Richardson, Dallas, Addison, Carrollton and Hebron.

Renner is located just north of the Dallas County line, and overlaps into two counties, Denfon and Collin, with most of it in Collin County. It is surrounded by six cities and any of them except Hebron could absorb Renner. The cities most likely to do so ore Carrollton and Addison.

There are two reasons that Dallas is interested in absorbing Renner. The first involves taxes. Renner lies right in the pathway of posh developments growing along White Rock Creek. Already swank developments, such as Prestonwood, have been built along the creek south of Renner, and similar developments are about to begin along the creek north of Renner. There is little doubt that if Renner is absorbed by a city which can provide it with municipal services, the same sort of high class development will appear in Renner, generating considerable property taxes.

The second reason is that if Dallas takes Renner, it might have a shot at eventually absorbing the tiny Denton County town of Hebron, which is the only way Dallas can break out to the north, reaching for more raw land. Carrollton also is looking at Hebron, so the Hebron issue is far from settled. Renner and Hebron could provide Dallas with a wedge between Carrollton and Piano. Otherwise Dallas is blocked from northward expansion.

The map also shows the largest property owners in Renner. The value of their land varies, but the most valuable land for residential development borders White Rock Creek, such as the land owned by the Haggar family, John Murchison, Robert Folsom and the McKamy family. In decending order, the largest Renner landowners are the McKamy family, Robert Folsom, Ray Hunt, Paul Pewitt, the Haggar family, Gladys Lloyd, Poston Investments, John Murchison and Trammel! Crow. Crow also owns another tract which is surrounded by Renner, and would be annexed if Dallas consolidates with Renner.

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Local News

In a Friday Shakeup, 97.1 The Freak Changes Formats and Fires Radio Legend Mike Rhyner

Two reports indicate the demise of The Freak and it's free-flow talk format, and one of its most legendary voices confirmed he had been fired Friday.

Local News

Habitat For Humanity’s New CEO Is a Big Reason Why the Bond Included Housing Dollars

Ashley Brundage is leaving her longtime post at United Way to try and build more houses in more places. Let's hear how she's thinking about her new job.

By Matt Goodman

Sports News

Greg Bibb Pulls Back the Curtain on Dallas Wings Relocation From Arlington to Dallas

The Wings are set to receive $19 million in incentives over the next 15 years; additionally, Bibb expects the team to earn at least $1.5 million in additional ticket revenue per season thanks to the relocation.

By Ben Swanger