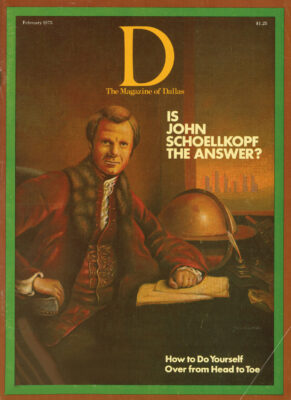

It is mid September, 1974, and John Schoellkopf has left an important establishment political session at First National Bank. The meeting has exasperated him, and the blast of grimy downtown wind that greets him as he swings through the bank’s revolving doors doesn’t help. Neither does the memory of six fruitless months spent beating the bushes for an establishment candidate in the upcoming mayoralty race.

The meeting had been one more in a frustrating series of attempts to pinpoint a candidate. John Stemmons, James Aston, Bob Cullum, and the rest of the “regulars” had engaged for an hour or so in the typical moaning about “Where did we go wrong?” But, once again, nobody had stepped forward with any concrete suggestions on how to recruit the right candidate. Before leaving, Schoellkopf had made it clear that it was time to stop talking and start doing. He simply could not do it alone.

For the past several months, he’d been trying to do just that. Ever since he and Stemmons began picking up talk of Wes Wise’s increasing absences from City Hall, his embarrassing financial problems, his disputes with the press, Schoellkopf had been searching high and low for a CCA challenger. The organization’s no-show in the 1973 race had been a tough pill to swallow. Now the once-unbeatable Wise was looking soft and vulnerable. It was an opportunity the establishment could not afford to pass up.

But that didn’t seem to have impressed the 100 or so prospects Schoellkopf had felt out for the nomination during the past few months. The young comers-Gilman, Raper, Humann-were still too young and too married to their business careers. The older men seemed too tired, too lethargic, or too out-of-touch. The headline-stirring meeting with the Big Boys at Republic during the summer to strong arm Aston into running had been a bust. Schoell-kopf’s face could still flush at the memory of the debacle. Not only had Aston turned his friends down cold, but the press had jumped on it with relish. Schoellkopf had agreed with Stemmons and the rest on Aston and had left town with the understanding that a discreet approach would be made. He returned only to read blazing headlines about “closed door meetings” and “top civic leaders huddle.” It was a blatant return to the oligarchy’s ways of old, and it was bound to stir up the smoldering resentments those ways had caused. What a way to launch a campaign against Wes Wise.

Meanwhile, back at the bank, the gentlemen who had stirred the earlier uproar were quietly reaching another decision. Stemmons was pushing for a consensus on the CCA’s mayoral candidate for 1975, and, before the men stood to shake hands all around, their nominee had been selected: John Schoellkopf. It made sense. The CCA had to defeat Wise in the next election; it was, in their minds, a matter of vital importance to the city. They obviously weren’t going to be able to talk any of the “old fogeys” into it. Even if they could, they couldn’t be sure the public would buy it. Johnny Schoellkopf was simply the only man with the independent wealth and the public image to take on the mantle. He was also the only young man they could “trust.” Sure, he’d sewn a few wild oats with the new CCA and in pushing for Adlene Harrison and Lucy Patterson. But he was still “one of them.” He always had been.

John Schoellkopf knew, as he returned to his office on the 12th floor of Main Tower, the conversation that was going on back in the bank’s conference room. He knew because he’d sensed the inevitability of his candidacy for some time. As early as 1973, trusted friends and political allies had been telling him that he was the only man in town who could take on Wes Wise and win. Several months of “thanks, but no thanks” from everyone from Aston to Russell Smith to Alan Gilman had convinced him that his friends were probably right. He had already decided he was, at the minimum, willing. But he still wasn’t sure it was what he really wanted. His political experience was limited; as a candidate, it was nil. An incumbent mayor like Wise was no pushover. Schoellkopf knew the “fatcat establishment” albatross would be hard to contend with. And there would be the snide “little rich kid” jokes.

And, of course, there was Erik Jonsson. The former mayor was dead set against Schoellkopf because of the “you’ve-never-worked-a-day-in-your-life” stigma. Stemmons could probably take care of Erik, but the silver spoon stigma would be hard to shake. Still, he was ready to run. He even wanted to run – provided, of course, the old guys were solidly behind him and put their money where their mouths were. Looking at it square in the face, though, he had to admit he was more than a little scared by the whole business. It would be harder than anything he’d ever attempted. Never in his life had he suspected that at 36 years of age he’d be forced to make his mark as a candidate for mayor of the City of Dallas.

Six years ago, John Schoellkopf had his life quite neatly in order: He was sitting on his hands waiting to become publisher of The Dallas Times Herald.

It was, as everyone knew, only a matter of time. He was Jim Chambers’ boy. He had been since that day in 1957 when he had gone to Uncle Jim and found a spot in the Herald newsroom. Four years of prep school in Connecticut, and a year at SMU (like Wise, Schoellkopf never finished college) had made him want to get out and flex a little. The original idea had been to write the Great American Novel, but he didn’t happen to have a friend like Chambers in the book publishing business.

The newspaper publishing business seemed the next best thing. After a few months, there was little doubt in anyone’s mind that John could go places at the Herald. Chambers had been a longtime friend of the Schoellkopf family, a distant cousin, and sometime golfing partner to his father. The Schoellkopf name was as good as gold in Dallas. Schoellkopf was born, as Dallas author A. C. Greene puts it, into “a town full of uncles.” His great-grandfather had been one of the original Dallas merchants, a leather goods dealer. His grandfather brought big money into the family by marrying the daughter of J. B. Wilson, the cattle-banking magnate of the early 1900’s. His father had made another bundle in real estate. His mother had been for years a leading matriarch of Dallas society. On top of that, Chambers had been without a protege at the Herald for years, and, like any powerful man, he was beginning to wonder who would carry on. It would take a lot of hard work, but Schoellkopf knew he had the inside track.

It wasn’t long before the handwriting was officially lettered on the wall. While Schoellkopf never distinguished himself as much more than a hard-working, aggressive, modestly talented reporter, he began surely and swiftly to climb the Herald ladder. First, he ran through the choice reporting beats: county courthouse, City Hall, and, finally, a two-year stint in the Washington bureau. Fellow reporters dubbed him “Times Herald staff nephew,” a designation that stuck for years.

After a few years in the newsroom, Chambers moved Schoellkopf to advertising, then to promotion, then circulation, until, at barely 30 years of age, he was named vice president in charge of administration. As one Herald veteran would later reflect, “Not bad for a college dropout who didn’t know how to type when he got here.

I don’t know if Chambers ever really believed that deeply in John,” he continued. “But he certainly did believe in his name.”

Meanwhile, Schoellkopf had shown himself to be bright and competent enough to make his meteoric rise to Heir Apparent a little easier for older colleagues to stomach. In the late Sixties, when the paper was having trouble with its circulation fulfillment (the department that makes sure the customers get their newspapers) Chambers gave Schoellkopf carte blanche to clean up the mess. Not only did he straighten out the fulfillment problems, he restructured the entire department. The paper gained more circulation in the 11 months he headed it, Schoellkopf likes to point out, than it had in the previous 11 years. “That should go some way in dispelling the idea that I’ve never worked and never managed,” he says today. “I’d be the last one to say that my relationship with Chambers didn’t help me. But I think my accomplishments stand on their own.”

There is a peculiar respect for Schoellkopf among former colleagues. “He was an unpretentious rich guy,” recalls A. C. Greene, a former editor. “He lived in an unpretentious apartment, drove a car like everyone else’s, and he never picked up the lunch tab more than anyone else. I think he tried really hard not to be the ’rich kid’ type. People liked him for it.”

Councilman Garry Weber, who was Schoellkopf s roommate during those years, remembers the same sort of unpretentiousness. “He didn’t swear off his wealth, but he never seemed hung up with it, either. He was never really extravagant when I knew him. He was kind of a messy housekeeper, though.”

But even while the general consensus agreed with the Herald old-timer who once said Schoellkopf was “about as good a rich kid as you could ever find,” he could never quite shake the fact that he was different. He would often quite innocently forget to pick up his Herald paychecks, not out of any snobbishness, but because his family money was more than sufficient; he just didn’t pay much attention to things like salary.

In the summer of 1970, John Schoellkopf’s precisely charted future quite suddently fell apart. The Herald was selling out to The Los Angeles Times. Chambers would remain as publisher on a long and lucrative contract- which the Times had also offered Schoellkopf-but things would never be the same. Schoellkopf could no longer rest easy that the publisher’s chair was in the bag. As he’d later explain, even if he did eventually make it to the top, someone in Los Angeles would always be hovering over him. If he couldn’t have it his way, the way he’d planned all these years, he didn’t want it at all. After vigorously arguing against the sell-out, John Schoellkopf waited only a few months after the deal was consummated, and then left the paper.

The next year was to be his first intimate experience with the peculiar milieu of the young and born-rich. He set up an office and began telling people he was in “investments,” the way he’d heard so many men do long ago at the country club when he was a kid. He played golf, hunted, watched the market. He tried his hand at civic projects. He and his brothers dabbled in East Texas rural real estate.

But the good life can be boring, even to a man accustomed to it. The city elections were coming up in 1971, and Schoellkopf heard that CCA Councilman Doug Fain was making noises about not running for re-election. Working his way through several civic projects, Schoellkopf had found himself hobnobbing with top members of the oligarchy. Erik Jonsson had even asked him to head the bond program for the new City Hall. Schoellkopf decided that if Fain did drop out, he’d make a run for the vacant slot. It seemed a safe bet.

Soon enough, Fain decided to go ahead and run. Worse, the bond program was put off. It looked as if Schoellkopf would have to wait a few more years to enter the Inner Circle.

Then one day he was invited to lunch by CCA operative Tom Unis. Unis mentioned that CCA President Dow Hamm wanted out. The rest of his talk was vague, but Schoellkopf sensed he was feeling him out for the CCA presidency. He didn’t quite know what to think. He was definitely interested in politics, but behind-the-scenes kingmaking wasn’t what he had in mind. He’d have to give it some thought.

A couple of weeks later, Schoellkopf was invited to a meeting in Unis’ office. When he walked into the room, he knew he wouldn’t be able to turn down their offer. He scanned the faces in the room: Stemmons, Cul-lum, and the others. Unis started the meeting. They were concerned about the age-old organization’s image. For the first time, the CCA was receiving less than favorable press. This young upstart Wise was looking like he meant to give CCA-backed mayoral candidate Avery Mays a run for his money. The wounds from the First National-Republic feud over Charles Cullum were still very tender. And, finally, the “old bulls” were just plain tired. They needed some young, if not necessarily new, blood. John was the only young man who fit the bill. Schoellkopf knew that, too. He accepted the mantle. He had no choice.

Following Mays’ defeat in 1971, Schoellkopf began to pick up the pieces. As he saw it, the loss to Wise was bad, but not nearly so worrisome as the close shaves some CCA council candidates had suffered in their races against unknown independents. The CCA seemed to have fallen into bad graces with the electorate. Stemmons agreed, and went halvsies with Schoellkopf on an in-depth public opinion survey on the CCA. The results were just what Schoellkopf expected. The passing of time, the influx of young out-of-towners, and the growing sophistication of political minorities were beginning to take their toll on the organization. People thought of the CCA in terms of its cliquishness, its conservatism, and its narrow-minded business orientation. That image, Schoellkopf felt, had to be changed and changed fast. (Of course, one suspects the voters had always felt somewhat negatively toward the CCA. But they had always supported it because they trusted its style of governance. It’s one thing to ask a harried buck private if he “likes” his drill sergeant; quite another to ask him if he’d prefer someone else to lead him into enemy territory.)

Schoellkopf’s cosmetics were simple enough: If the voting public thought the CCA too cliquish, all he had to do was open up the process a little, devise “neighborhood” meetings where every Tom, Dick and Harry of every race, color and creed could come and “apply” for nomination to the slate. If it was the conservatism that’ rankled the critics, he could easily add some broad liberal rhetoric to the campaign, maybe even place a couple of genuine liberals on the slate. And the minorities were a must. No lily-white, WASP council slate this time. They’d need another black in addition to George Allen; they’d need a Mexican-American and at least two women.

The “neighborhood” meetings notwithstanding, the real decisions were made by the executive committee. There was a lot of in-fighting. Stemmons wasn’t so sure about this Lucy Patterson woman, a black social worker, and he didn’t want the group to endorse George Allen for a third term. He also had a few questions about this outspoken crusader from Jewish North Dallas, Adlene Harrison. And there were complaints from the Mexican-American community about Pete Aguirre, a wealthy architect whose relationship to the chicano community apparently ended with his last name.

But Schoellkopf was prepared for this. He’d stacked the selection committee well enough to joke casually with reporters about the splits in the voting. Stemmons was really the only one to worry about; and he seemed satisfied with the re-endorsement of Russell Smith, the addition of conservative Charles Storey from Oak Cliff, and the booting of Garry Weber.

One thing was still sticking in Schoellkopf’s craw: The CCA had no mayoral candidate. Jonsson was pushing hard for one; in fact, he’d even indicated he might go outside the group to find Mr. Right. Stemmons, on the other hand, counselled discretion as the better part of valor. No sense risking another humiliating defeat at the hands of Wes Wise, especially when Wise was proving to be harmless.

Schoellkopf saw Stemmons’ point, but the thought of a blank space under the CCA mayoral column bothered him. If the answer was not to take Wise on, maybe there was another angle. He reflected on the old adage that “if you can’t beat ’em, join ’em.” Well, why not? Why not have-the CCA endorse Wise? At least the group would be assured of backing a winner.

He tried the notion out on a few colleagues; pretty soon the phones were ringing off the wall. Jonsson and Stemmons were furious. Even the people Schoellkopf had placed on his new, broad-based executive committee grimaced at the suggestion. As one member argued, “It didn’t make any sense for the organization, revamped in response to what Wise did to Mays in 1971, to come back and embrace the guy . . .”

So, Schoellkopf returned to the task of electing the CCA council slate. Wise would run unopposed by a serious candidate, and un-endorsed by the CCA.

Schoellkopf’s campaign tack would be the “new CCA,” with an emphasis on the “new.” A fresh slogan was conjured, “The CCA is about people.” Young, dynamic guys like Michael Collins were brought in to sell it. Fundraising efforts were spread to younger and newer money, too, partly by design, partly because the older guys weren’t coughing up as they used to. Campaign rhetoric was expanded beyond the proverbial admonition that “what’s good for Dallas business is good for Dallas” to include environmental issues and transportation, what Schoellkopf liked to call the “people” issues.

Schoellkopf was, of course, apprehensive, but basically confident. He believed he’d done the right thing, and he was reasonably certain the voting public agreed. He believed, with a few exceptions, that Stemmons and the rest of his mentors were satisfied with a job well done. By the first week of April, when the election results were in, Schoellkopf was feeling pretty satisfied with himself. He’d blown the Zeder-Weber thing: Fred had played too much the heavy, and Garry had spent more money than a council candidate should. But the remainder of the slate, even controversial types like Adlene and Lucy, had made it. The public had bought his new look. It was obviously impressed by the broader ethnic and ideological facade of the slate. He had read the times correctly. Not bad for a young guy who’d taken on a job in 1971, admittedly not knowing a damned thing about politics.

Ionically, it is Schoellkopf’s greatest personal achievement, the “new CCA” he fashioned, that will come back to haunt him as a mayoral candidate in 1975. It was an achievement only on the surface, and the surface would soon crack. From the day the campaign got underway, there were suspicions that the “new CCA encompassed everything and stood for nothing.” “The CCA is about people,” blared the newspaper ads, and by saying nothing the slogan hinted at everything the new CCA council would become. The slogan seemed especially strange coming from the likes of Michael Collins, who is just-like-you-and-me except for the fact that he’s 30 years old and president of Fidelity Union Life Insurance Company and probably pays more tax on his stock dividends than most of us make in a year. It seemed awkward that Peter Aguirre, who lives in North Dallas, was suddenly referred to as “Pedro.” It seemed peculiar that Garry Weber was booted, but George Allen was handed an unprecedented third term endorsement. The “new CCA” was spouting a fresh, urban liberal line, and its candidates were running under an establishment banner and on establishment money.

The rich who dabble in liberal politics receive a strange and pleasant sensation, like a swimmer who finds himself being carried by a Gulf current; he is going with the tide and against it at the same time. Schoellkopf was the loyal nephew who could also afford to play the prodigal son. His candidates could feed from the establishement’s generous hand, while talking between bites about the need for “new priorities” and “quality, not quantity.” It was fun to mouth easy words like “relevance” and to warn white, middle-class audiences about the problems of the ghetto. It was even more fun to say the “right” things when you had no fear of being on the wrong side, when you were wrapped in the comfort of the establishment’s blanket.

And, sure enough, John Schoellkopf’s city council has run the city just as, two years ago, he had run its campaign. Never before has there been a council that has talked so much and produced so little. Only a handful of the items accomplished by the council were actually initiated and put into action by the new members themselves: the new city sign ordinance, the Park & Ride bus service, the Office of Human Resources, and para-medic training for ambulance personnel. The rest has been clean-up work on projects initiated under Erik Jonsson. The council’s energies seem to have been directed more to matters like the Great Councilmen’s Spouses’ Voucher Debate.

House liberals in politics often act like the house blacks of plantation days: They have a tendency to doubletalk. There’s one set of words, codes and inflections for the white folks in the Big House and another set for the field hands in the cabins. Recently, when an environmental committee proposed by Garry Weber, who is nobody’s house liberal, was approved, it was accompanied by a lot of the same high-minded talk that had characterized the “new CCA” campaign. Only at the last minute, a catch occurred when the council majority decided to delete one of the toothiest sections of the ordinance because it would, in their words, make them look as if they were against building and development.

The Southwest Airlines-Love Field flap was another classic. Here, at last, was a “people” issue that people were really upset about. It wasn’t simply the question of Southwest Airline’s legal rights, but the larger-and for the voters in North Dallas, more important-question of public convenience for commuter flying. The “people” were howling, but the “people’s” city council ignored the noise. It was too close to the edge, and one step over the line would leave a councilman irretrievably on the wrong side. The tide had changed, and the swimming was getting to be tough work.

Even Schoellkopf has found the going tougher. He still defends his candidates, saying “This council has been the most open-minded and hardworking council we’ve ever had.” But then the questions start coming, and he sidesteps: “I regret it hasn’t produced more of the things it has talked about and studied.”

Schoellkopf dances and prances around the subject because he knows where the questions will lead. Could it be that John Schoellkopf created this council in his own image? Can a man who planned to endorse the mayor he now wants to depose hold the strong beliefs prerequisite for leadership? Is the “new CCA,” as a city council, only an omen of John Schoellkopf as a mayor?

To hear Schoellkopf talk, the answer is no. “The mayor of Dallas has to be a man who makes things happen. An initiator. And yes, he has to be a man who is willing to stand up and say this is right and this is wrong.” That’s fine rhetoric to use in a campaign against Wes Wise, and there are few people who would argue with it. It’s back to the “CCA is about people” kind of slogan. It meets the times, yes, and it reflects what people are saying around town. But it’s one thing to describe the qualifications for a job, and another thing to meet them. The council he created has not been one to “stand up and say this is right and this is wrong.” Schoellkopf himself is open to the question of whether he knows the difference between what is right and what is wrong for Dallas.

He has yet to come up with a cogent philosophy. “I’m conservative on some issues and liberal on others,” he’s fond of repeating. Recently, when asked directly what his political mode of thought is, he replied, “I’ve been wondering that myself . . .”

“But I’ll tell you what I believe in,” he added quickly. “I believe that change is a part of our present society. You got to have city government that changes. You can’t have a rigid philosophy.”

Can you have any philosophy?

A little later, asked to be more specific about what he believes in, he answers, “That’s a tough question. I believe the economic well-being of a city is the key. Jobs, housing, civil tranquility, all of that is rooted in a healthy economy.” True. Everything Schoellkopf says is true.

Except when he’s pinned down. When a group of blacks met with Schoellkopf at the Bonanza Steak House on Ledbetter some weeks ago, a young man from East Dallas pressed Schoellkopf on his attitude toward single member districts. The candidate was clearly between a rock and a hard place: The establishment was, is, and always will be against single member districts. If the system is ordered by the court, the official establishment line is to push for a system which includes as few single member districts as possible. The official liberal line, on the other hand, is for a system that would elect all 10 councilmen from districts and only the mayor city-wide.

The young man in the audience kept pressing. “If the court ordered a 10-1 system,” he asked, “would you fight it?”

Schoellkopf stared at the floor for a full 30 seconds. “I’m going to have to dodge that one,” he finally said. “I’d have to talk to the attorneys. I’ll say this, I wouldn’t fight an 8-3 system.”

“Yeah, but I asked if you’d fight a 10-1 system …” The question was lost, as Schoellkopf pointed to another raised hand.

An elderly black lady asked a substantive question about sanitary conditions in the ghetto. Schoellkopf shuffled, and said, “I don’t live in any ghetto, but I know about rats …” Then he was off on another subject.

Later, a black leader came up to say that he felt the firing of SMU President Paul Hardin had been a lousy deal, and Schoellkopf replied, “Yeah. I don’t know. I’ve heard a lot about it both ways.” A week earlier he had told two North Dallas businessmen in no uncertain terms that Hardin’s firing had been necessary because Hardin simply wasn’t performing.

At the beginning of the meeting, Schoellkopf had outlined his platform, delivered with the easy confidence that comes to a politician when he has something specific to say. Number one was the need for “assigning priorities,” which the group later learned was a way of saying “Dallas can’t solve all her problems at once.” Number two was the stock rendition on downtown revitalization, which included one highly interesting twist already recommended by the council inner-city committee: a proposal to change state tax law to allow municipalities to give private developers tax abatements on property taxes in order to encourage development in depressed areas. Number three was Town Lake, which he is for, and which, furthermore, he thinks “we should go ahead and put on a bond program.” (At that point one fellow in the middle of the room turned to his companion and whispered, “Has anybody told him about the state of the economy yet?”). Number four was a standard pitch for law and order, including “taking a hard look” at increasing the police force by 10 per cent or more. Number five was the need for a full-time, salaried mayor, a statement he concluded by explaining, “I don’t need the money myself, but . . .” Number six was the need for better and tougher representation in Austin and Washington, and how he had worked in both places.

It wasn’t a particularly exciting campaign speech, as campaign speeches go. “Nothing in it,” one observer remarked, “that makes you want to bring on Kate Smith and sing ’God Bless America.’”

But campaigning is new to John Schoellkopf. As the campaign progresses, you can bet he’ll learn the right words and moves. If he’s anything, he’s a fast and agile learner. Whatever he missed by skipping through the school of hard knocks, he makes up for with slick imitation. Life had not prepared him to be publisher of the Herald, but he was ready. Life did not teach him to be the savvy kingmaker of the CCA, but a good mind and an eye for adaptability were enough to get him by. No, the John Schoellkopf we’ll be watching in the coming weeks will be a presentable candidate. Probably presentable enough to win.

John Schoellkopf as mayor would be more interesting to watch than John Schoellkopf as candidate. As he says, “A mayor has to dance among the special interests.” To understand what he means, you only have to recall the recent controversy that erupted over a bank-office development that was approved by the City Plan Commission for the Turtle Creek corridor. The preservation of open spaces has been a major trumpet of Schoellkopf’s CCA. But in this case, the developer was Martin Tycher, one of Schoellkopf’s good friends and a contributor-to-be. The Plan Commission is also composed of Schoellkopf’s good friends, including, until recently, his wife. The Plan Commission not only gave its approval, it modified the ordinance to allow Tycher the right to avoid strict rules precluding office buildings. All in the spirit of friendship, as they say.

Ultimately, friendship is Schoellkopf’s major handle on politics, so the Turtle Creek case may not be an isolated example. He understands political alliance in terms of personal bonds. He believes himself when he says, “I’m essentially going to run five or six different campaigns in different areas of the city. I’ve got friends in every part of the community.” He thinks his friends are his greatest asset.

But they may be his major liability. John Schoellkopf likes to please his friends. But a mayor who “stands up and says this is right and this is wrong” is never going to please everybody, even his friends.

His other liabilities are the inevitable result of the one overwhelming fact of his life: He was born rich. “The rich are very different from you and me,” Scott Fitzgerald wrote. To which Robert Benchley would reply, “Yes. They have more money.”

The qualities, including money, that make the born-rich different become more apparent when they enter politics. They have funny, and often fatal, blindspots. Nelson Rockefeller, for all his management smarts and strengths, has never grasped the essential political fact of life that you cannot govern by purchase. John Kennedy, for all his vision and charisma, could not understand the simple truth that the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse cannot be eradicated by writing more and larger checks.

To grow up viewing the world through the picture window of the Brookhollow dining room is narrowing. Almost as narrowing as viewing the world through the cracked and grimy window of a tenament apartment. The born-rich, like the born-poor, are unavoidably placed on the sidelines: They are only observers of the fundamental experience of this society, the middle-class experience. Our politics, like our culture and our morality, are little more than a microscopic mirror of that experience.

The intelligent and effective politician is necessarily the man born and bred of the middle class. He is at home with the give-and-take, the inherent hypocrisy, the sudden and relentless shifts of wind, the endless moral paradoxes of American politics. He is the only one hungry enough.

For the born-rich, politics is too often another expensive pasttime to break the boredom of being rich. But politics, at the minimum, must be taken seriously by politicians. It is not the place for dilettantish dabbling; it has to be a matter of life and death.

It is hard to tell whether frivolous dilettantism brought John Schoellkopf to us. We know he was born with no-blisse oblige in his blood; we know this one social more of the rich has been good for this city. But we also know the men who ran this city best, the Erik Jonssons, the R.L. Thorntons, the Fred Florences, were quite a different breed of rich from John Schoellkopf. They were middle-class men who earned their fortunes, their reputations, their social statures. Each earned his right to lead.

John Schoellkopf’s “uncles”- the Jim Chambers, the John Stemmons – won’t be able to guide his every step as mayor of Dallas. The job is far too complex and the pressures are far too demanding to be handled by easy cosmetics and easier slogans.

The crux of the problem with John Schoellkopf is suggested by the billboards he already has erected on North Central Expressway. The billboards say simply, “Schoellkopf . . . . leadership.” Leadership to what end? Leadership for what purpose?

John Schoellkopf is not certain, because the CCA is no longer certain what it will take to navigate Dallas through her most difficult and trying era. The electorate-at-large is confused, too; it’s hard to determine if its confusion is the cause or the result of the CCA’s suddenly blurred vision. We know if John Schoellkopf is elected, he will be elected, like Wes Wise, with no clear-cut mandate from the city. But we also know, despite all the long-winded textbook theories, that The Constituency rarely does order specific mandates, and more often than not, does not know what it needs until it sees it.

A young businessman made that very point over lunch at the City Club a few weeks ago, and added: “John’s bright, well-bred, and has a knack for saying the right things. But that’s hardly enough anymore.”

His luncheon companion rose to Schoellkopf’s defense: “Look, I’ve known Johnny for years. He hasn’t had much of an opportunity to show us what he’s made of, but he’ll rise to the occasion.”

“What you mean,” the other businessman countered, “is that he’ll make it look like he’s rising to the occasion. He’ll go through all the motions; he knows the forms, but what about the content?

“In a way,” he said, turning to me, “I’m more worried about Schoellkopf at City Hall than I ever have been about Wise. For one thing, Wise has performed in the role of mayor as he saw it, representing the city, while leaving the nitty-gritty work to the city manager and the city fathers. But John will give the appearance of firm leadership, and others will be hesitant to step in because they’ll think John is doing the job. And the job won’t get done.”

The three of us fell into silence. At a nearby table weoverheard two older gentlemen discussing the same point.Schoellkopf’s friend nodded in their direction and remarked, “I suppose the argument is going on all overtown.”

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Local News

In a Friday Shakeup, 97.1 The Freak Changes Formats and Fires Radio Legend Mike Rhyner

Two reports indicate the demise of The Freak and it's free-flow talk format, and one of its most legendary voices confirmed he had been fired Friday.

Local News

Habitat For Humanity’s New CEO Is a Big Reason Why the Bond Included Housing Dollars

Ashley Brundage is leaving her longtime post at United Way to try and build more houses in more places. Let's hear how she's thinking about her new job.

By Matt Goodman

Sports News

Greg Bibb Pulls Back the Curtain on Dallas Wings Relocation From Arlington to Dallas

The Wings are set to receive $19 million in incentives over the next 15 years; additionally, Bibb expects the team to earn at least $1.5 million in additional ticket revenue per season thanks to the relocation.

By Ben Swanger