Later today, the Dallas City Council will hear from transportation planners who want to run an elevated 7-story tall, high-speed rail line from West Dallas through the southwest corner of downtown on its way to the Cedars. The bullet train would extend to Fort Worth. The difference between us and our neighbors to the west? Tarrant County’s portion would operate below-ground, while downtown and West Dallas get to make room for an enormous piece of infrastructure.

Plans for this bullet train have come into focus in recent months, mostly during occasionally prickly discussions in a drab gray boardroom in Arlington where the North Central Texas Council of Governments, or NCTCOG, allocates billions of public dollars for transportation projects in 17 North Texas cities, one town (Addison), and eight counties. The bullet train to Fort Worth has rapidly become a priority for the NCTCOG’s director of transportation, Michael Morris, who hopes to plan this extension west in parallel to Amtrak determining whether it can build its own high-speed rail from Houston to Dallas.

Some of Dallas’ representatives have gotten crosswise with their suburban colleagues over how the train is expected to surface. The NCTCOG is now holding back $100 million in funding for six unrelated transportation projects until the Dallas City Council signs off on the plans for the elevated rail line, a move that hasn’t gone over well with all of the Dallas bloc. A few of the more outspoken Dallas representatives—Councilmembers Cara Mendelsohn and Jesse Moreno, in particular—want more information as to how the line would affect existing infrastructure and businesses as well as future plans for economic development.

“This is to force us to do something,” Mendelsohn said of the stalled funding, “and I think we deserve to know the full scope of what the project is.”

The current discussion shows the difficulty of regional transportation planning, where suburban interests can conflict with the reality on the ground in urban cities. For instance: the proposed alignment includes stops in Dallas, Arlington, and Fort Worth. Fort Worth would get a subterranean rail station beneath its downtown, resulting in little conflict with existing buildings. Arlington, which famously has no public transit beyond city-supported ride share, is planned to get a subway near its entertainment district. Eventually, the line could be a direct connection to a bullet train from Tarrant County down to Houston.

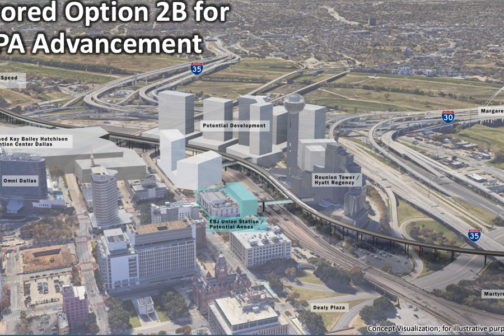

Dallas, meanwhile, must figure out how to make an elevated piece of right of way coexist with what could wind up being $10 billion worth of new public and private investment in a corner of downtown that has slumbered since the Dallas Mavericks moved out of Reunion Arena in 2001.

The extension to Fort Worth is a complementary project to the long-planned bullet train to Houston, an effort that is now being led by Amtrak, after the private effort to fund and build it failed. The NCTCOG now believes that the project “looks viable” because of Amtrak’s involvement. And so it is aggressively pursuing an extension from Dallas to Fort Worth, which would be built and operated separate from the Houston project.

The push for the elevated rail line in Dallas and not Fort Worth is somewhat complicated. The federal government has already signed off on a 7-story tall high-speed rail station in the Cedars, the neighborhood just south of downtown. For efficiency purposes, the NCTCOG wants its Fort Worth train to pull right in, scoop the Dallas passengers, and begin the 90-minute trip to Houston without a transfer. Changing the station, Morris has said, would require new federal approval.

Council Member Cara Mendelsohn has been the most outspoken of her colleagues at the RTC meetings about slowing things down: “You would not want your city to have to vote for something when you don’t have all the information,” she said.

The problematic rail line would surface near Hampton Road in West Dallas on its way downtown and into the Cedars, 75 feet into the air. The organization believes it paramount that riders will be able to continue to Houston without having to transfer from a subway. This so-called “one-seat ride” is why the NCTCOG sees no other option for the alignment than an elevated structure through West Dallas and the southwestern edge of downtown.

“You would not want your city to have to vote for something when you don’t have all the information.”

Councilmember Cara Mendelsohn

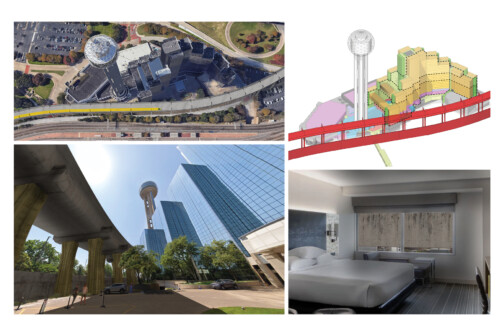

The federal government signed off on the station in the Cedars in 2017, years before voters gave their permission to spend $3 billion on a new Dallas convention center adjacent to the planned line. The Trinity Park Conservancy, after years of dithering, finally has decided to build the Harold Simmons Park above the levee in West Dallas; the line will sail over portions of the park. Hunt Realty Investments, which owns 25 acres near Reunion Tower and the Hyatt Regency, has announced plans to build a $5 billion mixed-use development next to that convention center. They don’t believe their plans and the rail line can coexist.

“This is an area of significant financial investment,” Mendelsohn said during a meeting last December. “Many of you are aware of the new convention center, which will cost several billion dollars. We are expecting this to be a walkable area; we don’t need trains running through it. And we will not accept trains running through it. I don’t know how else to say it.”

The transportation board directed Morris to study tunneling the entire route, but the presentation Council will hear appears to only include the problem of wait times. He predicts that traveling up from a subway to the rail station, which is expected to be a vertical distance of 185 total feet from below ground, would add a delay of more than 20 minutes. Instead, the presentation shows examples of transit centers in Toronto and San Francisco that promise increased density, higher towers, and integrated mixed-developments linked by skywalks.

Hunt Realty has been on the offensive. The company ordered renderings showing how the rail would affect its future plans and the existing Reunion Tower and the Hyatt Regency hotel. The proposed alignments vary slightly, but they’re both elevated immediately east or west of the properties. Hunt’s renderings show concrete blocking out hotel rooms and bisecting the 25 acres the company owns just south of Reunion Tower. City Hall sources say the company’s representatives have been meeting privately with public officials and sharing the renderings ahead of Wednesday’s briefing.

“If the high-speed rail happens as it’s planned, it’s going to physically sever the new convention center from our site, and it will physically prevent new development happening on our site,” says Colin Fitzgibbons, the CEO of Hunt Realty. “All it’s going to do is increase the risk for the success of this convention center for the city.”

Hunt has owned the land for decades, and Fitzgibbons descried the convention center as the “catalyst” the company needed to move forward with a large investment. (Previously, Amazon’s HQ2 was the catalyst it was waiting for, but that didn’t work out as planned for Dallas boosters.) Hunt envisions the land holding towers with more hotel rooms to support the convention center, as well as retail, office, affordable and market-rate apartments, and open space.

“A mixed-use district must spring up around the convention center for it to be successful, 360 degrees around it,” Fitzgibbons says. “There’s going to have to be so much of this around for the convention center to work, because right now, there’s not much to do in that corner of downtown Dallas.”

The NCTCOG proposes possible pedestrian lobby connections with the Hyatt Regency as well as a pedestrian deck plaza that could be built above the rail line. Whether or not Hunt’s worst-case scenario comes to fruition—major changes to the hotel’s access points, pulling available rooms off the market because of proximity to the rail, an inability to build its planned towers—the discussion about the rail’s impact to Dallas has mostly happened away from the city, among the regional transportation planners and suburban members of the transportation board.

“As a council member who represents portions of downtown Dallas, the Cedars and the convention center, this project will have a big impact on my constituents and business owners alike,” Moreno said in a meeting last month. “I would like to ensure that my colleagues and I have an opportunity to learn more about this project.”

The NCTCOG is one of 450 Metropolitan Planning Organizations across the United States, which gather the local governments within a region to coordinate regional transportation planning. It makes its decisions based on population estimates that show a growth of more than 4 million North Texans by 2050, which, if present trends hold, will increasingly choose to live in the suburbs.

This was the topic of a recent study by the Center for American Progress, which examined the makeup of Metropolitan Planning Organizations, including the NCTCOG. It found that the policy boards prioritize decisions that “are typically skewed toward suburban and exurban elected officials.”

And while the study mostly explored the wildly disproportionate allocation of public dollars toward highway expansions over transit, it also showed how difficult it is for cities like Dallas to make itself heard once the rest of the board aligns around a project that will benefit the region.

The Dallas City Council hasn’t passed a resolution in support of the high-speed rail, but its members are nearly unequivocal that they would love to see a bullet-train. The concern is in the details, and downtown and West Dallas are in the way.

Author