The ambitious, often contentious project to bridge Dallas and Houston by high-speed rail has stolen the spotlight from the active notion of running bullet trains between the two largest cities in North Texas.

The North Central Texas Council of Governments, the entity responsible for securing state and federal funding for local transportation projects, is preparing to enter a planning phase to establish an alignment for high-speed rail between Dallas and Fort Worth, which would include identifying station locations and early conceptual engineering. The NCTCOG hopes to receive environmental clearance from the federal government by the end of this year, which would formally kick off the effort to fund the project. It has been studying the issue for a decade.

The Dallas City Council was briefed on the matter this week, during a meeting of the Transportation and Infrastructure Committee. Running trains 40 miles between Fort Worth and Dallas seems a far more likely, and forthcoming, outcome than building a line to Houston.

While the Houston route has been environmentally cleared, the private company that has acquired land to build the line, Texas Central Partners, is in shambles. Amtrak is now researching whether it wants to partner with the organization and take the reins. Meantime, the line between Dallas and Fort Worth doesn’t depend on acquiring much private land. That is what stirred up an organized opposition to the Houston route.

The NCTCOG says about 90 percent of the land along the likely Fort Worth alignment is in the public right of way, which means the tricky part is navigating existing infrastructure impediments such as highways, not negotiating land deals. Until the trains get to Dallas.

The existing plan is to run the line from downtown Dallas to downtown Fort Worth adjacent to Interstate 30, with a stop in Arlington. The NCTCOG anticipates that Fort Worth’s and Arlington’s stations would operate below ground so the route won’t interfere with the freeways. (Arlington will also need to formally enter into an agreement with a public transit provider like Dallas Area Rapid Transit before being guaranteed a station.)

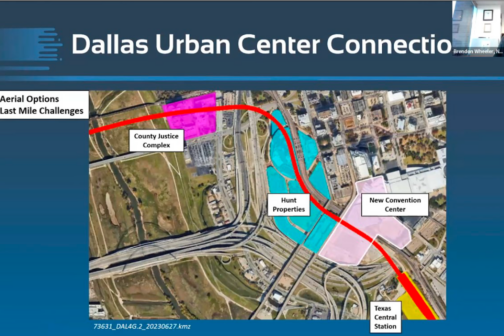

Trains would surface near West Dallas, as they head to a planned station in the Cedars, just south of downtown, which has already been approved by the federal government. The 10 percent of privately owned land lies mostly in Dallas. It is concentrated in the southwest corner of downtown, where nearly $10 billion of public and private investment is expected in the coming years. If the trains run through the Cedars, the new convention center and Hunt Realty’s vision of towers on its empty property below the Hyatt Regency and Reunion Tower will need to accommodate a new neighbor. (Or, more literally, a new house guest.)

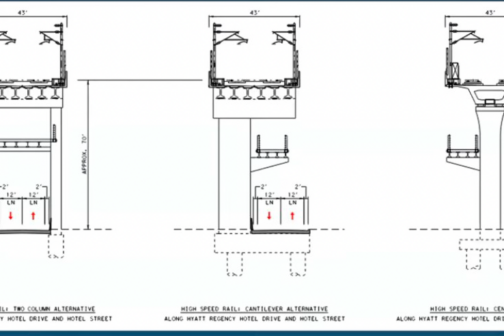

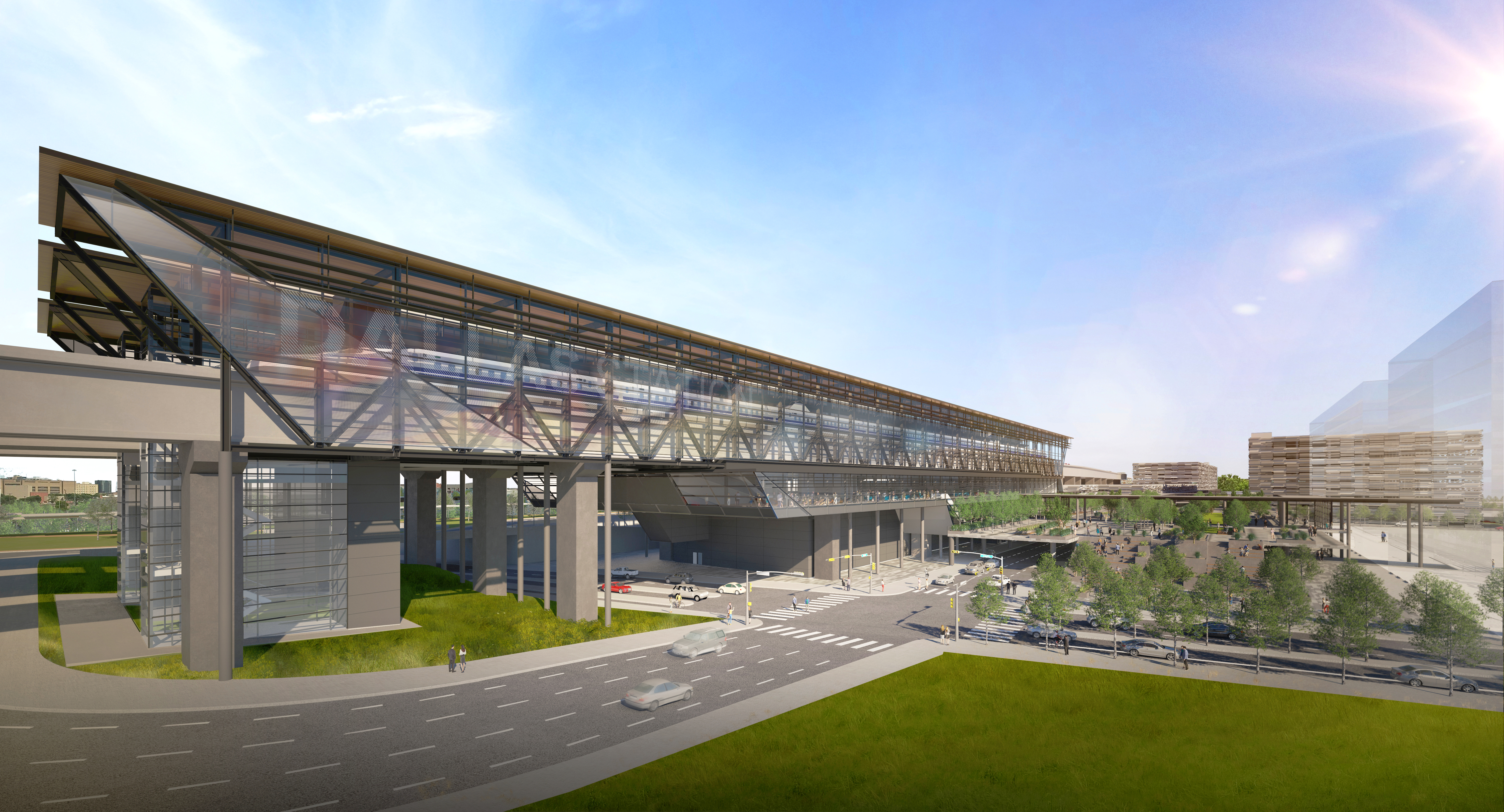

The sticking point is how those trains get to the Cedars. For one, that station already has federal approval, and should the line to Houston ever materialize, an elevated route through downtown would provide a “one-seat ride” from the state’s largest city all the way to Fort Worth. But the station is planned to be about seven stories high, which is why the agency chose the rail to be above-ground in Dallas. This is where things get complicated.

The present alignment would surface near Hampton Road as it heads east, past the planned location of Harold Simmons Park in West Dallas. It would follow the existing Union Pacific line over the Trinity River. Brendon Wheeler, a program manager for the NCTCOG, showed a slide to the High Speed Rail Alliance during a presentation last August that depicted a line possibly traveling through the Dallas County Justice Complex before heading south through Hunt’s property and the new convention center on its way to the Cedars.

The elevated station near Southside on Lamar is expected to rise 70 feet and the NCTCOG would prefer to have the trains pull right in, which has drawn concern from several members of the Dallas City Council in recent months.

“My sole issue is the loss of any contiguous land in downtown,” said Councilman Chad West, who represents North Oak Cliff. “When we lose open space in the city for economic development, housing, corporate campus relocations for a transportation item, whether it’s a new highway or even a train, which I support, I think we’ve got to take it seriously.”

Michael Morris, the transportation director for the NCTCOG, referred to the possibility of running an elevator from a subway station up to the taller platform, expressing concern that riders would grow frustrated with having to haul their luggage. “The loss of ridership in that situation will reaffirm the decision of three years ago that the best solution is to create a seamless connection,” he said. “You sit on your train for two minutes and keep going, but we’re reexamining that as requested.”

“We need to have a one-seat ride to Dallas to Houston to make our line make sense,” Wheeler said during the August presentation. “Dallas to Houston being further along, they established they needed to be aerial due to the constraints they’re dealing with as they head south. We’re pretty much tied in at that point where the Dallas station is, both vertically and horizontally.” Which means: The NCTCOG would prefer not to tunnel through Dallas.

But plans for the southwest side of downtown are not what they were in 2017, when the COG first floated the path from Dallas to Fort Worth in a report to the Federal Railroad Administration. The biggest change is the forthcoming convention center, a more than $3 billion project that will be built near the high-speed rail’s proposed path. Hunt Realty, which owns more than 20 acres of land behind Reunion Tower, plans to spend $5 billion building a mix of towers around where Reunion Arena once stood. Next door, the Dallas Morning News in 2019 sold its longtime headquarters to Ray Washburne, who envisions new development spreading from his property north to the West End, capitalizing on pedestrian traffic from the convention center.

In December, some Dallas City Council members who serve on the Regional Transportation Council began loudly voicing their concerns. Can all that development survive if the high-speed rail infrastructure is not placed in a tunnel?

“I don’t understand how we are investing in something that will be to the detriment of Dallas that will benefit others,” Councilwoman Cara Mendelsohn, of Far North Dallas, said during a meeting last month. “It’s necessary for there to be a solution where this is below-grade for Dallas.”

Morris seemed to have seen these protests coming. Last month, he received approval from the regional transportation board to increase a consultant contract by 10 percent to study tunneling the entire route. The city of Dallas sent a letter on January 8 that formally requested that the COG study tunneling.

“We can answer your question: How does a tunnel go under the Trinity River?” Morris said. He just needed approval to spend more money to study it.

The city of Dallas, meanwhile, is looking to package the station with the existing Eddie Bernice Johnson Union Station and perhaps some sort of pedestrian transit mall that would zip riders and conventioneers from the rail station to surrounding hotels and the convention center. The city views the wildly underused Union Station as a potential mixed-use hub, where Amtrak, the Trinity Railway Express, and DART would continue operating alongside bars, restaurants, and retail. City staff presented Denver’s successful redeveloped Union Station as a comparison. As for the transit mall, staff showed Council an example of how Dubai links its rail to a shopping mall.

All of that, sans maybe the plans for EBJ Union Station, are renderings and drawings. The ultimate goal would be to go even further with high-speed rail, connecting not just to Houston but to Austin, San Antonio, and Laredo. But even Morris acknowledged that without the longer legs, a stub from Dallas to Fort Worth alone doesn’t make much sense.

“It seems very unlikely we would want to build high speed rail between Dallas and Fort Worth if we did not have a leg that connected us to all the other Texas cities,” he told the Council on Tuesday.

In the interim, the COG is holding its money tight. There are five other projects within the city of Dallas that Morris said were now on hold, “pending further discussion and resolution of this high-speed rail issue.” Spokesman Brian Wilson notes that funding those projects “may be impacted by future funding for high-speed rail and other associated projects in or near downtown Dallas.”

Those projects have little, if anything, to do with high-speed rail outside of how they are funded. Morris informed the Regional Transportation Council of their status last week. They include a $5 million project to build parking near Interstate 45 and Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard in South Dallas, adjacent to the Forest Theater. Another is a $30 million cost overrun for what Morris called the “West Dallas Gateway,” which would be a “complete street” project that runs from Trinity Groves under the Union Pacific line to Main Street downtown. A $20 million rebuild of Harry Hines and Mockingbird was included, as was a $12 million pilot test to redesign Harry Hines to use AI and other technology that would trigger traffic lights for first responders heading to the Southwestern Medical District.

The fifth project was a $10 million pedestrian-focused reconstruction of the area around downtown’s Thanks-Giving Square, to coordinate with planned private improvements.

Mendelsohn, who sits on the RTC, said she interpreted the announcement “almost to be a threat.”

“I’m not trying to threaten you. I just don’t think we can have selective regionalism,” Morris said last week. “I don’t think we can say we’re all together on this, then after 10 years of being all together we’re no longer together on this.” (The NCTCOG began studying the possibility of high-speed rail from Dallas to Fort Worth in 2014. It took three years to complete its first report.)

This entire situation shows the complicated manner by which major transportation projects get planned. There is an unbelievable amount up in the air over high-speed rail. Amtrak received a $500,000 federal grant in December to continue researching the stalled high-speed rail project from Dallas to Houston. Transit watchers are skeptical. David Peter Alan, a longtime writer for Railway Age, told Texas Monthly that “half a million to study something is a pittance.”

Texas Central received the same federal clearance the COG is seeking for the Fort Worth line in 2020, and Morris said that an approval from the federal Surface Transportation Board would permit construction to begin. But Texas Central appears like it will need help from Amtrak in order to build and operate it.

The most recent cost estimate for the Dallas-to-Houston project is $30 billion. The COG’s 2017 report estimated that it would cost $11.3 billion to build high-speed rail to Fort Worth from downtown Dallas. Mendelsohn this week asked Morris whether it would cost $12 billion to build the line, to which he responded, “it’s nowhere close to what it costs to build between Dallas and Fort Worth.”

There are a lot of questions suddenly facing the city of Dallas. First, the NCTCOG will have to study what it would take to tunnel high-speed rail beneath the city. As for city staff and the Council, they will have to weigh whether a bullet train to Fort Worth can coexist with the ambitious vision for a historically quiet corner of downtown that is suddenly very attractive.

Author