In 1990, Oak Cliff tried to split from Dallas. After decades of City Hall mismanagement and neglect, some residents felt the Cliff would be better on its own. Writing in the Dallas Morning News amid the furor over de-annexation, journalist Bill Minutaglio compared the proposal to the breakup of the Soviet Union. In his estimation, Oak Cliff secessionists wanted to turn their neighborhood into a “Lithuania-on-the-Trinity.” Cold War humor aside, the statement contains a larger truth.

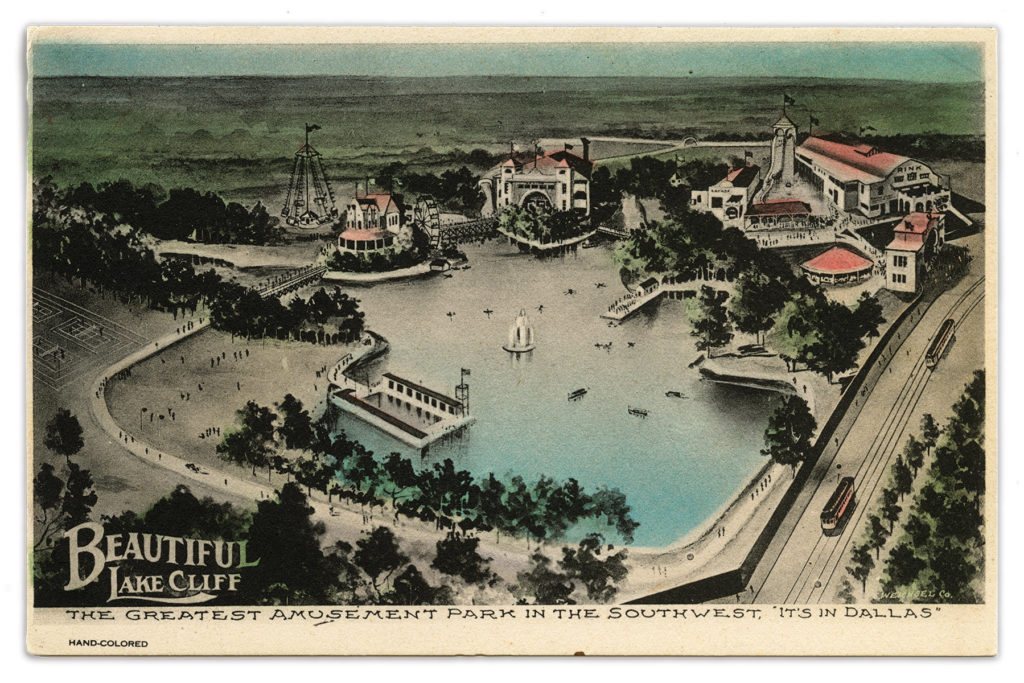

Oak Cliff has been called a lot of things. It was once “the Southwest’s greatest playground.” Later, it was the city’s “red headed step child” or “Dallas’ own Jerusalem.” Then there was that reference to a Baltic republic. What runs through those comparisons is that something was just a little different here. It was a neighborhood a bit out of step with the rest of the city. Maybe Oak Cliff just hasn’t quite been Dallas enough for Dallas. This view has, historically, permeated City Hall. For decades city leaders have been all too comfortable disregarding the black and brown residents who have long called Oak Cliff home. The hardening lines between the north and south of this city have left folks below Interstate 30 wanting reflective representation on the City Council and improved access to city services.

Later this year, they may have one of their own in the middle seat of the council’s horseshoe.

As this May’s election draws closer, some candidates in the race to succeed Mayor Mike Rawlings have deep ties to Oak Cliff. Scott Griggs has represented North Oak Cliff on the City Council since 2011. Albert Black grew up in South Dallas and built a successful business in Oak Cliff years later. Jason Villalba is an Oak Cliff native, but now lives in North Dallas. This isn’t the first time, either. Former Mayor Laura Miller called North Oak Cliff home before she moved to Preston Hollow.

Historically, Oak Cliff residents have been uncomfortable with their second-class status in the city. Change has been halting, incremental, and incomplete.

When Oak Cliff was chartered in 1890 it was, essentially, a resort town. With Lake Cliff as its hub, Oak Cliff attracted Dallas’ wealthy with promises of rest and recreation—a stark contrast to the hustle and bustle of business north of the river. In 1893, Oak Cliff, like the rest of the country, was gripped by a financial panic. Tourism dollars dried up. Facing mounting financial problems, Oak Cliff reluctantly agreed to annexation in 1903. The measure passed by 18 votes.

Over the subsequent decades, Oak Cliff retained its distinctive character. Trying to make sense of the city in the aftermath of the Kennedy assassination, Neiman Marcus executive Warren Leslie highlighted Oak Cliff’s difference, or more appropriately by 1964, alienation. “Oak Cliff is unfashionable,” Leslie wrote. Any ambitious young man who moved to Dallas would do well to avoid the neighborhood as he would soon find “that by living in Oak Cliff he and his wife are out of the mainstream of Dallas life and that his children will grow up out of this mainstream.”

During the next 20 years the racial composition of Oak Cliff changed dramatically. Black and Latino residents became the majority throughout much of the neighborhood.

Until the 1970s, Oak Cliff—and the rest of southern Dallas for that matter—had been shut out of city politics. The at-large election of the City Council ensured its members were little more than toadies of the city’s moneyed elite who made up the Dallas Citizens Council. During the 1970s and 1980s, the fight against this unfair system became the focus of Dallas’ civil rights movement. Activists like Al Lipscomb, Roy H. Williams, and Marvin Crenshaw agitated for single-member City Council districts that would better represent the city’s growing diversity. Change was slow to come. By the late 1980s three of the 11 City Council seats were still elected at large and only two council members were black: Lipscomb and Diane Ragsdale.

A court-mandated reorganization of the Council finally eradicated at-large districts in 1990. But this decision—the crowning achievement of the Dallas civil rights movement—set off a chain of events that threatened to split the city in half. Some Oak Cliff residents felt this was just another example of City Hall ignoring what was best for their neighborhood.

In April 1990, the City Council voted for a plan that expanded it to 12 members—all elected from single-member districts. In response, the Oak Cliff Chamber of Commerce agitated for separation from the city. Under the leadership of Bob McElearney, the Oak Cliff Chamber saw the Council’s reorganization as an attempt to dilute Oak Cliff’s already limited influence by dividing the neighborhood among a number of competing districts drawn to ensure African American and Hispanic representation. Councilman Charles Tandy, who represented the predominantly white area of North Oak Cliff, said the plan “destroys Oak Cliff as we know it today.” As Tandy saw it, the secessionists were responding to decades of neglect: “There’s never been a mayor that cared anything about Oak Cliff.”

Critics charged that the Oak Cliff secession campaign was racist, as white residents in the neighborhood sought separation instead of minority representation. Roy H. Williams, the co-plaintiff in the federal lawsuit that ultimately forced the Council’s redistricting, did not mince words when talking about the Oak Cliff Chamber’s de-annexation plan. “The Confederacy still lives,” Williams said. The campaign had nothing to do with the unfair relationship between Oak Cliff and City Hall but instead was “about African-Americans and Latinos coming into power.”

McElearney dodged those charges—in fact, he asserted the new Oak Cliff would be far more diverse than the old Dallas—and instead focused on the significant disparities in city services and investment between northern and southern Dallas. He pleaded his case for separation on NBC’s Today Show. Over the last 25 years, he argued, only 20 percent of the city’s public bond money had been spent in Oak Cliff, an area that was half of Dallas’ total land mass and home to a third of its population. The independent Oak Cliff would consist of everything south and west of Interstate 35. With inadequate city services and failing infrastructure, Oak Cliff simply had not flourished under City Hall’s (mis)rule. As McElearney concluded, “This is a very sincere effort by the citizens of Oak Cliff to have self-determination.”

In an interesting twist, the secession movement’s focus on these disparities found sympathy among some of southern Dallas’ black leaders, most prominently Al Lipscomb.

Initially, though, Lipscomb was leery of de-annexation. Like many, he suspected the secession movement was about preserving white power in southern Dallas. But Lipscomb couldn’t pass up a potential ally in his fight for recognition, respect, and resources in his community. If anything, the secession movement forced City Hall to reckon with the stark disparities that divided the north and south. As a Dallas Morning News editorial remarked in its plea for unity, de-annexation “has forced city officials to acknowledge the tremendous asset Dallas has across the Trinity River.”

Lipscomb talked up the potential allies he found in McElearney and the Oak Cliff Chamber of Commerce. While before the Oak Cliff Chamber had “a stigma of being completely lily-white … that has changed.” In Lipscomb’s words McElearney was “a bright young leader” who had “concern for all the people of Oak Cliff.” Charges of racism notwithstanding, southern Dallas leaders like Lipscomb and the secession movement had similar goals. They both wanted an equitable distribution of city resources. They wanted Oak Cliff’s full integration into the civic life of the city.

This alliance would, however, prove illusory. Just four months after City Hall voted for the expansion of the Council to 12 single-member districts, its members approved a referendum on a plan that would expand the Council even more—to 14 members. Under this plan, white residents of North Oak Cliff would retain a council seat while the creation of new districts further south would allow for greater minority representation. Lipscomb counted the decision as a victory. His budding ally, McElearney, declined to accept the 14 member redistricting plan.

In Lipscomb’s eyes this refusal showed the secession movement’s true colors. “The hoax has been exposed,” Lipscomb charged. Even though the 14-member redistricting plan addressed the Oak Cliff Chamber’s supposed grievances with the Council, McElearney’s refusal to endorse the plan convinced Lipscomb that what the secession movement really wanted was “Anglo domination.” Other black leaders in southern Dallas rallied against the secession movement. Soon enough it was clear secession was sunk.

Though the secession movement failed, the issues it raised remained. The city assembled the “Blue Sky” Task Force to address some of the city service disparities the secession movement railed against. But its focus on “short-term, high visibility projects,” like repainting crosswalks and fire lanes, and landscaping in city parks and traffic medians, did little to address the systemic problems that disadvantage Oak Cliff. The next 30 years would continue to see the gulf between north and south Dallas grow—more of the same.

It’s understandable if observers see little new in folks like Griggs, Black, and Villalba. After all, Griggs represents a district that was the erstwhile hotbed of secessionists wanting to maintain control of their neighborhood in the face of social change. Black is a successful businessman–historically a recipe for success in mayoral elections–who calls affluent North Oak Cliff home. Villalba left the neighborhood long ago and found North Dallas a bit more receptive to his conservative philosophy; he believes his name recognition in his district provides a path to the runoff. None of this, though, is to say that the election of any of these candidates necessarily means business as usual. In fact, Griggs has repeatedly promised to be a “new kind of mayor” and his time on council suggests he has the know-how to deliver on his promise.

The election of one of Oak Cliff’s own to mayor would be symbolic of the changing relationship between the city’s sections. But as important as this kind of symbolism is in politics, it’s not enough–its not actual change. Thirty years ago, Oak Cliff had a chance to enact actual change. Cliffies (wisely) let the secession movement founder but they also let escape the opportunity it provided to actually address the problems that beset the neighborhood. Whether the election of Griggs, Black, or Villalba will actually bring the southern sector into step with the rest of the city depends on what they will do in office–only time will tell. But the weight of more than a century of divergence, neglect, and, as was the case in 1990, outright antagonism between Oak Cliff and the rest of Dallas won’t be lifted with mere symbols.

It will be up to the next mayor—and the elected representatives in these districts—to help further improve the things that Lipscomb, Williams, and Crenshaw called for.

Blake Earle is a postdoctoral fellow at the Center for Presidential History at SMU. He wrote this piece for the website of D Magazine ahead of the May 4 mayoral election.