With one sip, an avid coffee drinker might be able to taste nutty or fruity notes in a freshly brewed cup of coffee. But Jessica Keenan, the brand president and green coffee buyer for Ascension Coffee, can identify whether that nuttiness is more almond or hazelnut. She can parse if that fruitiness is acidic like grapefruit or sweet like a blueberry.

Keenan is a Q Grader for Arabica coffee, a certification shared by about 7,000 people worldwide and a measly 650 people in the U.S. The Q Grader program was created in 2003 by the Coffee Quality Institute and supported by testing standards established by the Specialty Coffee Association of America.

Keenan evaluates coffee beans through cupping, a method used by producers and coffee buyers around the world to check the quality of green coffee beans, which are coffee seeds that have been processed but not roasted. Scores range from zero to 100, with specialty coffees ranking 80 or higher. Keenan does this weekly, and it’s a process she takes very seriously. Q Grader scores can impact the lives of the people who make the coffee.

There is a reason there are so few Q Graders. The rigorous testing involves 20 exams over six days. Testing includes being able to grind coffee beans to the right size to being able to identify fragrances in a darkened room. Recertification to be a Q Grader must happen every three years. Simply put: Keenan’s taste buds are extremely qualified to judge coffee, and she can prove it.

I sat down with Keenan to talk about being a Q Grader and how that fits into her work at Ascension. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Was there a specific cup of coffee that sparked your love for it?

I think for most people, tasting coffees from Africa can be really eye-opening, especially growing up in the U.S. where people might be exposed to more traditional flavors. I remember tasting a specific coffee that was from Ethiopia and getting those unique flavors of fruits and berries and thinking, “Wow, you can get this florality and fruitiness in coffee?” and it being such a shock.

What was the Q Grader test like?

It’s really intense. The current iteration allows three days of preparatory time with the cohort that you’re taking the exam with, followed by three days of exams—20 different exams over nine different modules. And these things include both demonstration to prove you can execute the protocol from memory. [That] you can go and grind that up and you know how to pour and you know how to break the crust and do all the steps.

And then you’re also tested on your sensory skills or abilities. You have to not only triangulate in a darkened room with only red lights on, but you have multiple placemats of coffees and you have to identify which of the coffees don’t belong to each placemat using only your olfactory and your taste to identify that.

And then there’s also a test of controlled fragrances that you have to—in a darkened room—be able to identify. There are 36 total, and you get tested on 10 or 12, and you have to basically identify, in the dark, whatever these differences are.

Then there is a modality where you’re basically tasting the percentage or the strength of sweet, salty, bitter in a liquid. There are several tasting components. And then a 100-question written portion.

How do you cup coffee?

The first thing we’re evaluating is fragrance, and that’s the dry coffee. You have anywhere from three to five sample cups of the same coffee at each placemat. That is necessary to get a good sample that is representative of the whole because I might be contracting, you know, 100,000 pounds of coffee, for instance. I can’t cup [all of it], I’m gonna only be able to cup a sample. So, you’re expanding that sample set to include five cups so that you’re hopefully getting as many variations that might exist in the coffee as possible.

At any given time during a cupping session, you can have five, 10, 15 placemats on the table. Personally, I prefer to do eight cuppings at a time, so eight placemats of five coffees. That’s 40 cups that I’m cupping in one sitting. So you go from placemat to placemat, first evaluating the fragrance and identifying the components you’re picking up from your olfactory senses.

Then we’re adding in the water. The coffee grounds rise to the top of warm what’s called a crust, and at the four-minute mark, we go through with our spoon, and each cup has the crust broken one time. So, we’ll disturb those grounds on the top of the cup using a gentle stirring motion, careful to not over-agitate, because that will also impact the extraction of the coffee. Then we’re identifying attributes and then grading the quality of the fragrance. We’re looking for identifiable pleasant elements, or worst case scenario, unpleasant elements like phenol or mold, a chemical smell.

After breaking all of the crusts, we’re going to go through and we’re gonna scrape the tops of the coffee to remove any floating grounds so that we can then taste for our cups. The ratio is all the same, but each good lab might have a slightly different size vessel. Ours is at the 11-minute mark when the coffee reaches a temperature that’s safe to taste.

We dip a special spoon into the coffee. I like to pull up around half a teaspoon to three-quarters of a teaspoon of coffee. Then we’re going to slurp, trying to aspirate all of that coffee throughout the interior of our mouths and our palates. And the purpose of that is to try to get it to that olfactory bowl so that we can get as much of the sensory perception as possible. You can swallow it or you can spit it out—in a larger cupping setting most people are spitting it out. But you’re gonna go through, and you’re gonna cup each of the samples, tasting them, and then we’re grading them on that score.

When you grade coffee, where do those grades culminate?

There’s a collective of Q graders throughout the process who are revalidating this information to come to an agreed-upon consensus of the value of this coffee—the financial value of this coffee—based on quality.

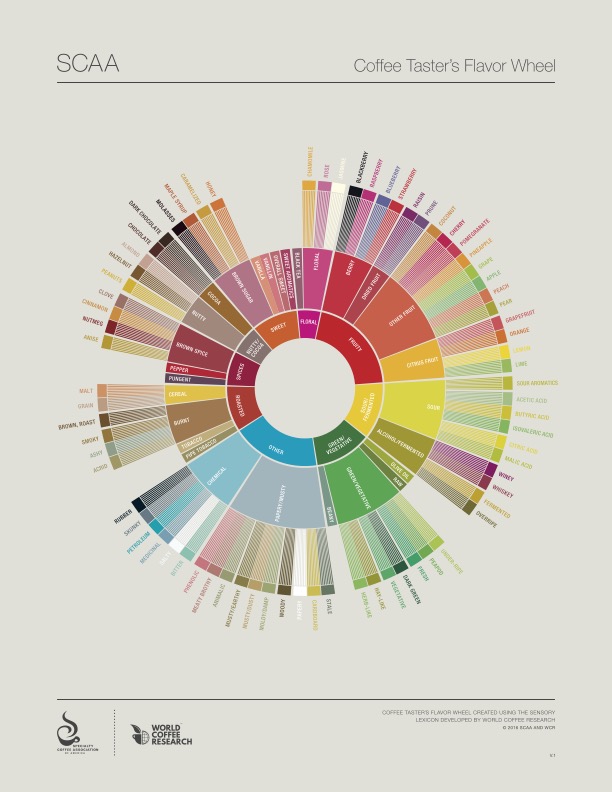

What’s interesting is with the cupping attributes, the descriptors may vary somewhat based on origin. Like, what fruits are available in Indonesia, for example, are going to be different than the fruits available in North America and what we’re used to referencing, but we can find those commonalities to understand if we’re referring to yellow or tropical fruits.

We might be referencing grapefruit, but in Indonesia, they’re referencing to Jeruk Bali, which is like a pomelo. That Q Grader language helps us to understand kind of what we’re talking about and identify the overarching flavors and then the score itself.

Does being a Q Grader play into what you do at Ascension?

Absolutely, yeah. It informs every decision I make from a purchasing perspective because I do all of our green coffee buying. Every green coffee that we’re buying is cupped and graded by me before I make a decision. I’m cupping coffees every week that we may never bring in—It could be offers from a producer we’ve worked with in the past and they’re very excited and want to share something with us.

It’s not possible for a company of our size for me to be traveling the world. It would be cost-prohibitive for me to go and be on the road 24/7. A lot of communication happens through sample exchange. So those coffees are coming to me unroasted and labeled to identify what they are, and then I’m gonna cup them and then make decisions about what I might want to bring in.

“We want to be able to reward those producers for what they’re making and the work that they’re putting in.”

Jessica Keenan, brand president of Ascension Coffee.

A lot of people are critical of Q Grader certifications. Why does it matter to you?

(Note: common criticisms of Q Grader certifications are that they are unnecessary, the tasting notes are tailored to Western taste buds, the scores are subjective, and the test itself is too expensive—about $2,000.)

I think there is value in being a Q Grader because the idea is that we’ve standardized the language. You might like this coffee more, but that should not be the direct impact of what score it receives.

We spoke earlier about the Ethiopian coffee and the berry notes—those can be unexpected flavors in coffee. Not everyone likes that. Not everyone wants to taste a blueberry in their coffee, [but] that shouldn’t impact the score negatively because the person tasting it doesn’t like that or doesn’t prefer that. The scoring should be based around the quality of the coffee or if the cup is clean—that’s what we call basically a cup that doesn’t have unpleasant attributes. There’s definitely agreed-upon unpleasant elements: phenol, rubber, tar. These are flavor descriptors that can be found in lower-quality coffee.

The genesis of the scoring system really came around because we had to find a way to differentiate this really unique-tasting coffee. We’ve got all this commercial coffee—over 95 percent of the coffee in the world is being produced in the commercial sectors, and that’s below 80 points—and they don’t cup that. They don’t need to do as much cupping and scoring. They might be tasting it. But they’re roasting it in huge volumes. They’re freeze-drying it for instant purposes.

Where I play, where Ascension plays, and where the cup score really comes into the conversation is in the specialty sector, and that’s the top 3-to-5 percent of all coffee in the world. And there, we do want to be able to differentiate. We want to be able to reward those producers for what they’re making and the work that they’re putting in.

Delicious coffee doesn’t just magically happen. It takes a lot of work and engagement and nurturance of the plant throughout the whole process of getting the coffee and the cherry from the bush itself, how the fruit is removed from the seeds, how the seeds are dried, and then how it’s roasted.

Author