The peeling sign on the brick facade reads “Ellis Pecan Company,” but 1012 N. Main St. wasn’t built to be a warehouse. Nor was it built to be a professional wrestling arena, or the home of Fort Worth boxing team the Golden Gloves, or a hall for dance marathons—though it’s been all those things in its history. Instead, 1012 N. Main St. is thought to be the only building in the world still standing that was built by and for the Klu Klux Klan.

The racist white supremacist group constructed it in 1921, rebuilt it even larger when it burned down in 1924, and used it as their headquarters in Fort Worth for about three years. It went through a few reincarnations before being sold to Ellis Pecan Company in 1946, which kept it as a warehouse until 1991. It’s been vacant, slowly crumbling ever since. Now, as the surrounding area undergoes major development for the Trinity River Vision Authority’s Panther Island Project, it’s time for 1012 N. Main St. to meet its fate—whether that be a wrecking ball or restoration.

Sugarplum Holdings LP, which purchased the property as an investment in 2014, applied for a Certificate of Appropriateness to demolish the structure earlier this summer. At a public hearing on July 8, the owners were officially granted the COA–albeit with a 180 day delay. It’s a time to “continue the conversation” around the former KKK lodge, as the city put it. And, for some community members, it’s the last chance to save what they see as an important opportunity for the city to reckon with its past.

“I’m thinking about what this building could do for Fort Worth in terms of reconciling our own history as a city, as well as reconciling our history as a country,” says Adam McKinney, co-director of DNAWORKS, an art organization at the forefront of the discussion. “We believe that it’s important not to be erased so that we can move through it together. I’m excited about the possibility of being part of a national conversation about healing race-based violence.”

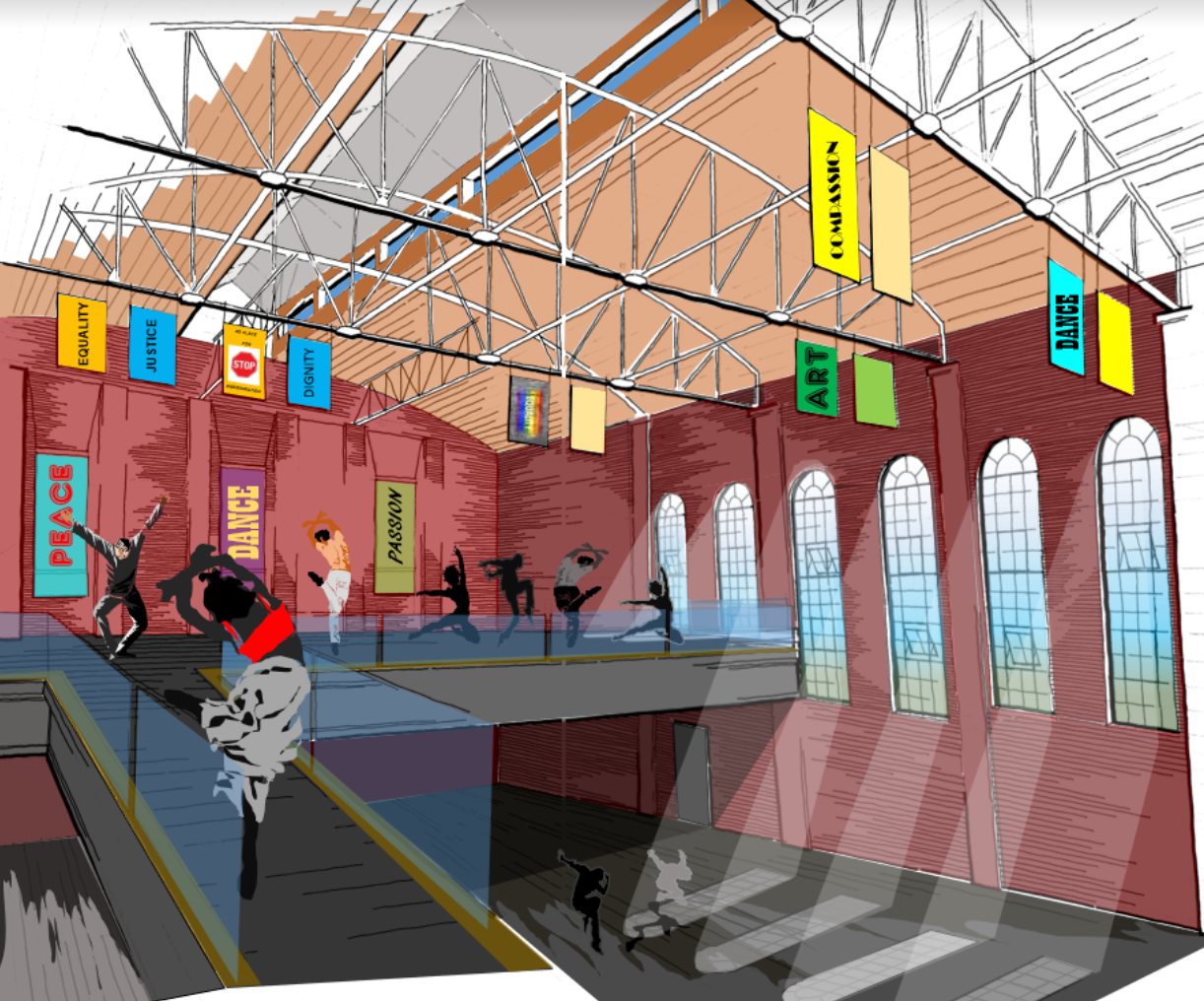

One of several groups interested in the space, DNAWORKS hopes to form a coalition with other organizations and use the building to create an international center for performing arts and community healing. DNAWORKS envisions spaces for performance art, workshops on restorative justice and liberation, and an educational wing that addresses the building’s history. Speaking at the July 8 public hearing, McKinney pondered the uniqueness of the situation.

“Never before in the history of the world, nor anywhere in the universe, ever, has a former KKK building been transformed in this way. Fort Worth, we have an exceptional opportunity to lead and model our commitment to equity through arts innovation.”

While the idea of turning a KKK lodge into a center for racial healing is certainly unconventional, it’s not entirely without precedent. The International Coalition of Sites of Conscience and UNESCO’s Sites of Memory have taken similar approaches to preserving landmarks with dark histories. The National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, Tennessee is one example. It was built upon the Lorraine Motel, where Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. It’s hard to ignore the glaring difference, though: the Lorraine Motel wasn’t built by the KKK.

In terms of transforming a point of trauma into an opportunity for healing, we’ve seen this kind of restorative justice enacted on a smaller scale in Dallas. Think of local artist and SMU visiting lecturer Lauren Woods, who’s known for her 2013 work Drinking Fountain #1. At the Dallas County Records Building, Woods created an installation to reveal the fading “Whites Only” sign etched into a marble wall above a water fountain. More recently, she’s been at the center of the conversation about Dallas’ most prominent Confederate monument, which is in talks of being either removed, transformed by Woods, or left alone. The artist is adamant that the monument stay and be reimagined, so that the stories of the oppressed can live in public memory.

When it comes to 1012 N. Main St, though, Woods is not convinced that it’s worth keeping around. This is not a statue or an object, it’s an entire building that is in need of significant investment. According to an engineering group hired by Sugarplum Holdings, the building will need between $8 and $10 million worth of work to get back into operating condition.

“The preservation argument isn’t strong for me because it seems like it relies on restoration—taking an object back to what it once was. In order to do justice or healing work, you don’t need to ‘restore’ the actual ‘thing,’” she says. “To me, the idea of the ruin is interesting—the opportunity presented has transformational potential that shouldn’t predicate itself on preservation per se.”

With the water fountain, for instance, she didn’t maintain the sign, she just made it visible as it slowly fades away. “So the poetry is in the actual real-time deterioration over time, which, to me, is a symbol of how progress is actually made as we chip away at oppression,” she says. “It’s also symbolic of what we hope for racist institutions—its eventual decay, its demise. The reality is that structural oppression may have slightly faded out of physical public sight, but it’s still there, it’s embedded deep within our country, as the white-only traces are in the marble walls of the records building, and we have to address it whether it’s in our face in the same way or not.”

Woods says she trusts artists’ visions and supports the idea of experimenting in the space, which DNAWORKS has done, “but the project of preserving to make it a racial justice center that people of color would have to launch a capital campaign for, that’s another thing that doesn’t quite reconcile in my mind,” she says. “The only way I can see the argument for preservation is out of an act of reparations—that building is donated to a black organization that can then leverage the property and its value to make money … There’s no justice in any of this unless there’s economic justice attached to it.”

With a POC-led organization at the forefront, DNAWORKS is confident that the larger coalition at 1012 N. Main St. would be beneficial to people of color, even if it does function as a non-profit (which is still to be determined).

“In terms of moving forward, thinking about the leadership of the coalition, we’re thinking about prioritizing people of color in order to subvert the history and ensure that we are thinking about the ways in which, historically, resources have been made unavailable to people of color in many ways, and subverting that as well,” adds McKinney.

With its soon-to-be waterfront location on the Trinity River and proximity to downtown, a cultural center at 1012 N. Main St. could become a valuable asset to the city. At the July 8 hearing, preservationists, historians, and community leaders were among those petitioning the demolition. The most compelling argument, though, came from a concerned citizen, Robert Rouse, on behalf of DNAWORKS. He’s the grandson of Fred Rouse, a Stockyards packinghouse butcher who was brutally beaten, shot, and lynched by members of the KKK in 1921, the same year 1012 N. Main St. was erected.

“When you’re raised on nothing but hate, that’s all you’re able to teach. You teach these things and other people have to pay. So we all get together and we try to come up with different formulas and try to color this over, make it go away like it never happened,” Rouse said. “Let’s turn it into a flower, maybe the bird might be able to enjoy it. Let’s turn it into something that people can’t recognize, especially black people, brown people, anybody but white. I like white people. But I’m a little disappointed in what’s going on now.”

For those who want to see 1012 N. Main St. remain, it’s a matter of acknowledging the injustice and hatred on which it was built.

“While I completely understand the intensity of emotion around this building, I think too much of the history of racism and race-based violence in the U.S. has been hidden and has been suppressed, and that clearly hasn’t worked for getting us closer to some kind of racial equity in this country,” Banks says. “As with all trauma, you can’t go around the trauma, you have to go straight through it for there to be any hope for healing.

Then again, the terrors of racism aren’t entirely in the past. Of the commissioners present at the July 8 hearing, one out of six voted against the demolition delay.

“In my opinion to leave this standing would perpetuate that racial problem that we have yet to really get a handle on,” said Billy Ray Daniels Jr., one of two blacks on a majority caucasian Landmarks Commission.

Even if the building is salvaged, its future is uncertain. There’s no guarantee that DNAWORKS and its coalition will be the future tenants. Banks and McKinney are still working on finding donors and forming the coalition. There are other interested parties, including the Military Museum of Fort Worth, which would like to put its own twist on the historic space.

“What I’m hearing is that there’s a fetishizing of architecture and the history of the object. But the building itself doesn’t and shouldn’t have the same symbolic value as say, the Confederate monuments,” Woods says. “It’s already served as what—a pecan factory? So, for me, it only makes sense to do the preservation work for the purposes of a racial reconciliation project if that land and that property and that restoration effort is being donated by the people who have benefited and profited from racism and oppression. And it doesn’t sound like that’s what’s happening.”

From what was said at the July 8 hearing, it’s clear that the Historic and Cultural Landmarks Commission is largely in favor of saving the building. Attorney Justin S. Light also made it apparent that Sugarplum Holdings, despite requesting permission to demolish it, is open to keeping the structure standing well beyond the required 180 days. Light declined to speak to D Magazine, and Sugarplum Holdings is staying quiet about its plans for the property.

In 100-and-something days, a decision may or may not be made about 1012 N. Main St. Until then, Fort Worth will be struggling to envision a bright future in the darkest corner of its past.

“There’s a way to repurpose this building so that nobody leaves unchanged,” says Banks. “I think it’s that very energy of the place that’s so painful that can also lead to healing.”

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this story stated that DNAWORKS is a non-profit, which is incorrect. The story has been edited to reflect that.