Glenn Beck has a story for me.

He often answers questions with stories. Full stories, with settings and characters and dialogue. A question about his regrets might evoke a story that involves Bono and Spider-Man and Beck standing in front of a floor-to-ceiling window, staring out at the New York skyline. A question about whether he’s reductive when he talks about American history leads to a story about a 100-year-old cane and the silent film Birth of a Nation.

This story, the one about Beck’s most recent evolution and his simultaneous move to Texas, begins on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. He refers to the day simply as “8/28,” meaning August 28, 2010, the day he held his Restoring Honor rally in Washington, D.C., on the anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech. He planned and talked about the event for a year before it happened.

“I thought it was to be political in nature,” he says. “But as I talked about it more and more, that felt more wrong, that it should be way away from politics. And then, when I walked off the steps of the Lincoln Memorial that summer, that’s the first time I felt like: ‘You’re standing in the wrong place.’ And that meant everything that I was doing.”

He’d assembled a massive crowd of devoted supporters, and at this point, he’d become an icon, the most outspoken voice in the budding Tea Party. But, for reasons he still doesn’t completely understand, something didn’t feel right.

“This poor real estate agent must have thought I was insane,” he says.

The real estate agent said, “What are you looking for?”

“I don’t really know,” Beck said.

The real estate agent said, “Do you want land or a building?”

“I don’t really know,” Beck said. “Show me a little of both.”

“A lot of land or a little land?”

“I don’t really know. Why don’t you show me a little of both.”

One of the first places he saw was the Solana development on Highway 114, in Westlake. And while he was intrigued by the weird colors and odd building shapes, he decided that the roofs and walls might not be able to support his heavy studio equipment.

His next stop was some empty land on the other side of the highway. At some point he asked the real estate agent to pull off the road so he could walk into a field and think. He strolled alone over a hill.

“I just needed a chance to talk to the Lord and say, ‘What am I doing? What am I looking for?’ ” he says. “I was actually wearing boots that day. Still with dew on my boots, I started seeing all the things I learned about the mistakes of Walt Disney.”

Glenn Beck is obsessed with Orson Welles and Walt Disney. He owns scrapbooks that once belonged to Welles and a first edition of a book that Disney carried with him for the last 10 years of his life. He says Disney didn’t structure his company the right way. He didn’t own enough, and he lost control of some aspects of his business.

As these thoughts came to him in that field, he says, he didn’t know what to make of them. Was he supposed to build an amusement park?

“That was quickly dismissed,” he says. “It was the lessons. I think the Lord was trying to say, ‘Learn the lessons from the storytellers before you.’ ”

Later that afternoon, he had a lunch meeting in the Hilton at Southlake Town Square. He was trying to explain to a different real estate agent what he was picturing. A small town. A look. A certain feeling. He was searching for the right words when he glanced down one of the streets of the town square. Red brick buildings, gazebos, mothers shopping, children playing by a fountain—there it was.

Some part contrived nostalgia, some part high-end consumerism, all of it sprinkled with good-looking suburbanites enjoying their day.

“I said, ‘It’s this. It feels like this.’ It’s so clean!”

So he talked with his wife, and they decided they’d move down the road, to Westlake.

•••

Most people think Beck went away when he left Fox. He didn’t. After coming to the posh suburban landscapes of Tarrant County, he took his talents to the internet, where dedicated fans can pay about $100 a year to subscribe directly. Vanity Fair and others have reported that he has about 300,000 subscribers (though there’s no way of knowing for sure). He broadcasts live on the radio for 15 hours a week and does his TV show for another hour every night. Alexa.com, a site that ranks internet traffic, puts Beck’s TheBlaze.com above Bloomberg, Gawker, and Reuters. He also has a movie studio, a clothing company, and his own imprint at Simon & Schuster—where he publishes not only his own books but also several other best-selling authors, in multiple genres. All told, he has about 300 employees, and tallying his various endeavors, Forbes put his 2013 income at $90 million—more than Oprah.

His headquarters are in Irving, in the building that used to be The Studios at Las Colinas. Just inside the locked front door, across from the receptionist and armed security guard, is a mural. It’s two stories tall and depicts a large man in a suit made of newspaper print. He’s lifting his foot to step on a smaller man, who’s holding a slingshot. Next to them are the words: DAVID SLEW GOLIATH WITH FIVE SMOOTH STONES. Across the head of the Goliath character is the logo of the New York Times. On the head of the David character is the logo of TheBlaze, Beck’s television network and website.

When I arrive, one of Beck’s publicists is waiting for me. We go through another locked door and step into a world of Beck’s own design. Glass walls reveal, on one side of the main hallway, a long conference table full of young people hunched over computers. A submarine stretching at least 20 feet hangs over them as they type. Behind them is an easel holding a poster with a quote from Ralph Waldo Emerson: “Imitation is suicide.” This, I’m told, is Beck’s think tank. He also calls it his “war room.”

Beck’s office is open, visible through the glass to anyone walking by. Five or six people walk out as I walk in. He has a scented candle lit on a table next to his “Disruptive Innovation” award from the Tribeca Film Festival. Soft music plays faintly from hidden speakers.

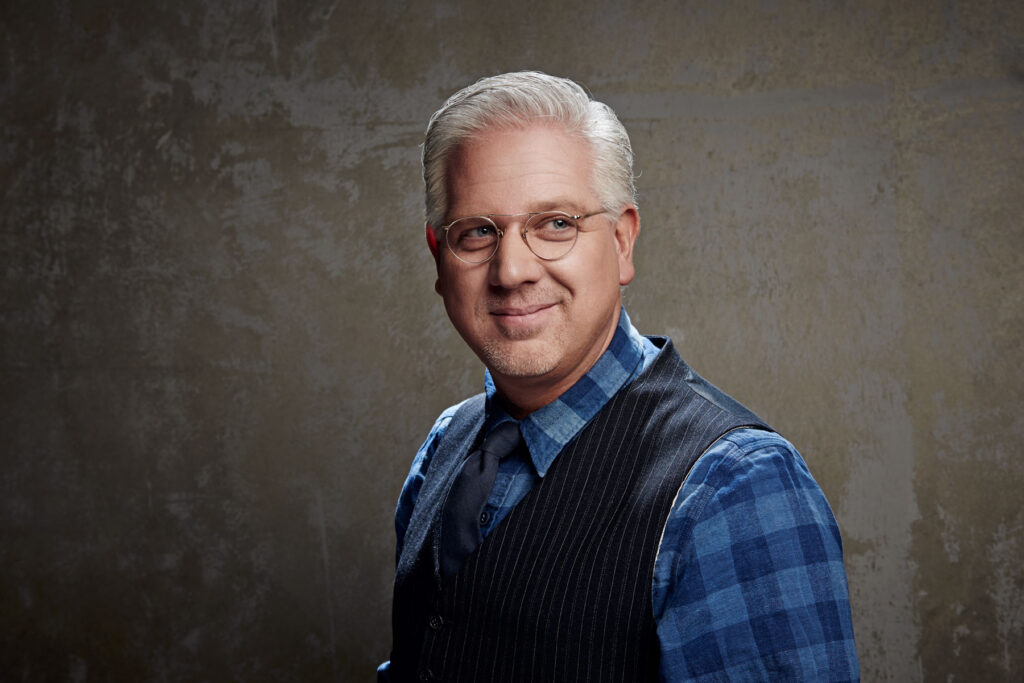

He’s finishing up a meeting at his desk when I spot him: the shock of white hair, parted perfectly, the startlingly blue eyes and round spectacles. Because of the lights and equipment, the rooms here are kept cool, so he wears jeans and a red cardigan sweater with a thick shawl collar, like he may have just been reading a book by a fireplace, even though it’s 94 degrees outside. The 50-year-old is the embodiment of avuncular.

I worked for two years to get an interview with Beck, since around the time of his Restoring Love event at Cowboys Stadium in July 2012. He still appears every so often in the friendly confines of Fox News, but he rarely grants outside interviews or cooperates with profiles.

So I went to his events. I talked to people at various levels of his organization. I listened to and watched his shows. I subscribed to his newsletter and read his books. And I read both book-length takedowns of him: Alexander Zaitchik’s Common Nonsense and Dana Milbank’s Tears of a Clown. I wanted to understand him, and I wanted to understand what has made him so successful. After renovating the studios earlier this year, Beck agreed to give me a tour—and to talk about his personal transformation.

He gives me a firm handshake and a pleasant greeting. When I fumble with my recorder and make an awkward joke about not wanting to hear my own voice, he erupts in uncomfortable laughter. His voice sounds like it’s being filtered through a microphone even when it isn’t.

“People are always surprised in meeting me at how quiet I am,” he tells me. “But that’s who I am. There’s a difference between—not in what I believe, but one is on a stage. You meet somebody who’s onstage, whether they’re reading someone else’s lines or, in my case, saying what I believe, there’s still performance value to that.”

So, for two hours on a Monday afternoon, we walk around his remodeled facilities in Irving, and our conversation covers everything from his affinity for storytelling to the destiny of the universe to whether he whitewashes history. I’m invited to ask him anything I want.

“As long as the American people hear the message that we don’t have to be this way,” he says. He often comes back to this, the notion that the country has become too divided. “I don’t think people want to be this way. I can’t tell you how many really profoundly liberal friends I have in New York, and they’re now saying, ‘Glenn, I feel the same way. I feel the same way.’ Good. Now we can make progress. We’re still gonna disagree with each other. But we can at least make progress.”

One of the most divisive political commentators in recent history, Beck trafficked in paranoia. He once joked about poisoning Nancy Pelosi. He characterized Democrats as vampires. During a show in 2009, he asked, “President Obama, why don’t you just set us on fire?” Not long after the Arab Spring began, he suggested that soon parts of Europe would become a caliphate, noting that when you combine the forces of Marxism with a radical form of Islam, “the whole world starts to implode.” He preyed on his viewers’ darkest fears while shilling for companies that sold gold, dried meals, backup hard drives, and silencers. He has apologized for some of the stupid things he’s said—like calling President Obama a racist. Now, he says he wishes he’d done some things differently. He knows he played a role in tearing this country apart. He’s calling for unity and wants Americans to be more loving and respectful of one another. And he wants to lead by example.

If you haven’t been paying attention—if Beck has slipped off your radar—he’s said and done a few things over the last year that might surprise you. He said liberals were right about the Iraq war, that we never should have gone in. He said he thinks Hillary Clinton will be the next president. He said he supports gay marriage—or, more specifically, that he doesn’t believe the government should have a say in anyone’s marriage, one way or the other. And this summer, he took truckloads of food and toys to immigrant children who had crossed the border into South Texas.

“I still have the same beliefs,” he tells me. “I’m still a conservative. But I just think that the country is best served by a smarter Glenn Beck. A quieter guy.”

•••

Credits