On the last night of his life, Kidd Kraddick picked out a stranger on a street corner in the French Quarter. It was a broiling evening last July in New Orleans. Kraddick had just left an oyster bar and had spotted the man selling pirated DVDs out of his trunk. Kraddick’s small entourage, a collection of friends and business partners, walked past the young man, nodding politely. But Kraddick stopped.

What are you doing? Why are you selling these? Don’t you know that’s illegal?

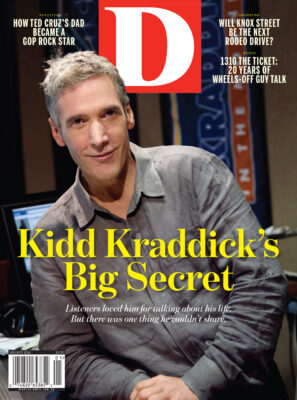

Kraddick’s friends, waiting for him, were annoyed, eager to get on with their evening. But that’s what made Kraddick one of the most successful radio hosts in the country—always asking questions, familiar with strangers, forever in search of a story. For decades, he had been plucking people out of crowds and putting them on the air, sometimes even giving them jobs. Kidd Kraddick in the Morning, broadcast from Kraddick’s own studio in Irving, was a ratings juggernaut that was syndicated across the country. He’d built that radio empire by taking an interest in normal people like the DVD hawker, changing their lives.

Lately, though, Kraddick had been making changes in his own life. At 53, he’d proposed to his girlfriend, who was 21 years younger. He’d apologized to his 23-year-old daughter for using her life as material on his show, sometimes without thinking about how it affected her. He had also begun to craft a succession plan to keep his radio show and his beloved charity operating after he was gone.

But on that night in the French Quarter, Kraddick thought he still had time. He stood on the street, listening to the hawker’s story. He was trying to earn money for school, hoping to become an accountant. Kraddick started talking numbers, testing the young man’s math skills. Impressed, he turned to his friend George Laughlin, the CEO of his company.

“Get this guy’s number,” he said.

Then Kraddick turned onto Bourbon Street with his friends, slipping into the crowds, stepping into the last 15 hours of his life.

•••

Kraddick had always moved a million miles a minute, manic, driven, restless. He forever seemed to be juggling his two cell-phones, wondering where he put his sunglasses, his keys, his coat, his car, opening his fifth can of Diet Coke, furiously typing a script for the show. He didn’t pay much attention to his health. Kraddick ate fast food, slept little, and smoked constantly (a habit he worked to keep from his listeners).

About four years ago, he began to look like he was paying the price for his hectic, unhealthy lifestyle. Already wiry and slender at 5 foot 8, he had shed pounds and taken on a pale, weak appearance. There were days when he didn’t make it to the studio, instead joining his co-hosts electronically from his downtown condo, his listeners never knowing the difference.

When people around the station quietly asked questions, Kraddick told them he hadn’t been feeling well, but he remained vague. Some turned to Kraddick’s best friend, Toby Wilson, to see if he knew anything.

Wilson is a tall, rangy attorney from Arlington who had known Kraddick for about 15 years and served as the president of his Kidd’s Kids charity. Wilson was one of the few friends who didn’t listen to Kraddick’s show. And he didn’t call him “Kidd.” He used his real name, Dave. Wilson knew what was wrong with Kraddick, but he wasn’t talking either.

That day, when Wilson and Kraddick pulled up to the eighth tee, Kraddick stayed in the cart, which was unusual. Always in motion, he’d rarely wait for it to come to a complete stop.

“I need to tell you something,” he began. “I’ve been hit with the Kraddick curse again.”

Despite his happy-go-lucky demeanor, in his quieter moments Kraddick tended toward pessimism. Whenever something bad happened to him, significant or trivial, he blamed it on the “Kraddick curse.”

“Oh, yeah?” Wilson said, chuckling. “What’s that?”

Kraddick looked at his friend. “I’ve got cancer,” he said.

Wilson paused, taking in Kraddick’s expression, waiting for a punch line. On his friend’s face, he saw only fear. Wilson sat for a moment, absorbing the news. Kraddick hopped out of the cart and headed toward the tee. Wilson had always relied on Kraddick to know what to say, to make uncomfortable moments lighter. But now, as they played the eighth hole, Kraddick swung his club in silence.

After they finished the hole, the twosome stopped at a snack shack for a soda. Wilson looked at Kraddick. “Do you want to stop?” he asked. It felt weird to finish the round. Shouldn’t they go back to the clubhouse and talk? Kraddick just laughed. He’d already shrugged off the seriousness of the moment. He climbed into the cart, and they headed to the ninth hole.

It was a glimpse of how Kraddick would handle the months ahead, the chemotherapy and radiation, the vomiting and hair loss. He wasn’t going to act differently, or stop doing his radio show, or feel sorry for himself, or burden anyone with his illness. He wanted to keep playing.

As they continued along the course, Kraddick told Wilson what he knew about his illness. It was lymphoma, and he had already begun an aggressive course of chemotherapy. The treatments left him weak, and he needed someone to drive him back and forth to the Arlington Cancer Center. He swore his friend to secrecy. He didn’t want anyone to know—not his co-hosts, not his listeners, not even his daughter. (Only with this story has his illness become public.)

It was ironic, really, that a man who had become so successful by talking about his life on the radio would choose to keep such news quiet. Part of it was just his personality, Wilson thought. He was a professional extrovert, but Kraddick could also be deeply private.

Of course, there were business reasons to keep his diagnosis under wraps. Would radio stations across the country continue to buy and air his show if they found out Kraddick had cancer? Would current affiliates let their contracts expire and sign other shows, preparing for the worst-case scenario? Telling business associates would add complications that he could avoid by keeping quiet. And if his co-hosts happened to find out, it was in their best interest to keep quiet, too. Their fates—and livelihoods—were tied to Kraddick’s.

But perhaps the biggest reason, Wilson believes, that Kraddick wanted to keep his health issues quiet is that he didn’t want to be pitied. Wilson’s 20-year-old son, Alex, was killed in a car crash that same year. Kraddick had been close to the young man. He watched how others began to treat Wilson. When he walked into a room, pity radiated. It’s who Wilson became, someone who elicited sad eyes and uncertain words.

Kraddick wanted no part of it. He refused to become “the sick guy.” His job was making people laugh. Cancer wasn’t really something to laugh about.

•••

Kraddick started his first radio show when he was about 12 years old, using a CB radio in the early ’70s. He began talking at the same time every night from his twin bed on Parkwood Drive, in Dunedin, Florida. Breaker One Nine. He got his friends to listen, and his small audience grew across the middle-class neighborhood of stucco houses, station wagons, and basketball hoops. He called himself Dreamcatcher.

As the youngest of four children—born David Peter Cradick—attracting attention was a survival skill. The family’s currency was not who could throw the ball farthest or earn the highest grades, but who could crack the funniest joke. “Put a microphone in our family and good luck getting it back,” says his older brother, Gary.

Kraddick landed his first DJ gigs in high school, working part-time at a local roller rink, driving around with boxes of records in the back of his rust-colored El Camino. He lay in bed at night, listening to his favorite DJs on WLS in Chicago, then imitated them, recording himself talking and playing music on cassette tapes for a station he called WJAN, named after his big sister, Jan.

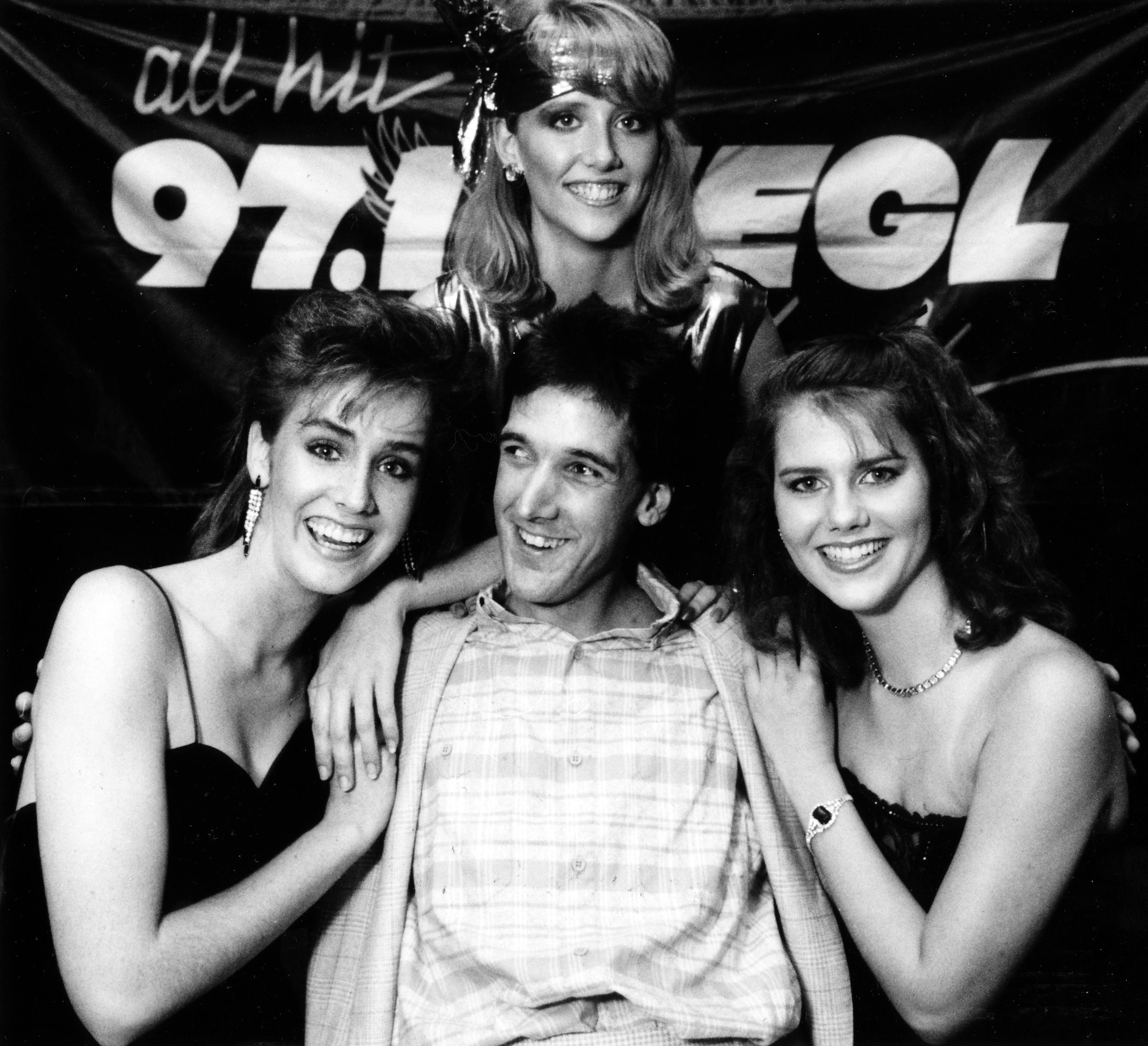

He went to the University of Miami but dropped out after a semester and enrolled in a 10-week broadcasting class. He landed an overnight shift at a small radio station in Sarasota, Florida. Then a program director at a bigger station, Q105 in Tampa, offered him a job. Right away, his ratings exploded. He was 18. Whenever there was a task no one else wanted to do around the station, a small event or promotion, the program director would say, “Get the kid to do it.” The nickname stuck.

By the time he was 25, Kraddick had landed jobs, lost jobs, gotten hired, been fired, made money, and found himself dead broke. His short career had been so tumultuous that he contemplated giving up. But then, in 1984, he was offered the nighttime spot at KEGL 97.1 The Eagle, in Dallas. Kraddick didn’t have money or a car to get to Texas, so his oldest brother, Lynn, loaned him cash and a Volvo station wagon. If he got fired, his family thought, at least he could sleep in the back of the car.

Kraddick had a youthful voice, and the teen audience of The Eagle, then a Top 40 station, eagerly adopted him. He talked to them about crushes and sex and other embarrassing pubescent concerns. He achieved a sort of boy-band popularity, booking appearances at skating rinks and malls, shouting out his trademark, “Howdy, baby.” Matthew McConaughey once admitted that he had impersonated Kraddick to get into Dallas nightclubs.

As the years passed, Kraddick began to wonder how long he could hang out at teen discos. His own life was transitioning. He now had a wife, a toddler, and a house in the suburbs. He was in his early 30s, but everyone still called him Kidd and expected him to behave like one. Kraddick got a daytime show, but in 1992, The Eagle dropped its Top 40 format and resurfaced as a hard-rock station.

At 33, Kraddick was out of work. He was still under contract, though, entitling him to two more years of his full salary, which friends speculate was in the six figures. The contract barred him from taking another job in the Dallas market.

Friends remember this period as “Dave in his underwear.” He would hang out at his house in his boxers, depressed and restless, planning a comeback. While he waited, he and a friend, JB Hager, went to work in Kraddick’s upstairs office, launching two new businesses. This was before Google, before the internet as we know it even existed, and there wasn’t a centralized place where DJs could find bits and wacky news stories. Kraddick, who had always been a gadget guy and computer geek, dragged Hager to a computer-parts swap meet in downtown Dallas, a market where “guys who lived in their mothers’ basements swapped computer parts and porn,” Hager says. Kraddick created a bulletin-board system, or BBS, a computer with a bank of modems behind it that DJs could dial in to and share information. Many people weren’t familiar yet with home computers, and the men spent hours on the phone explaining how to use them.

“Kraddick basically taught me, and the whole radio industry, how to get online,” Hager says.

The second business the men launched was an industry magazine, The Morning Mouth. They interviewed top radio personalities across the country. Both services were revolutionary. DJs went from clipping items out of newspapers to receiving a daily trove of material to talk about on air. It also connected the industry, in some ways making it more of a brotherhood. Both businesses did well, and he eventually sold them in separate deals, making more than $7 million, according to a business associate.

Still, Kraddick desperately wanted to get back behind a mic. He began talks with Gannett Company, which owned KHKS and was relaunching it as a Top 40 station called 106.1 KISS FM. He begged The Eagle to release him from his contract. After eight months, they did. Gannett couldn’t match his salary, but Kraddick didn’t care. He agreed to a two-thirds pay cut.

•••

On his first day back on the air in 1993, Kraddick was ebullient, cocky, ready. He prank-called rival morning shows on air. “I’m going to kick your butt, buddy. I’m going to own you!” he shouted into the phone. He wasn’t sure, though, if anyone was listening to the new station.

They were. KISS soared from 23rd in the ratings to third. Kraddick came shockingly close to trumping the two longtime kings of local morning radio, Terry Dorsey at KSCS and Ron Chapman at KVIL. That was across the board, in all demographics. His target audience was female, moms ferrying their kids to school. For the next 20 years, his show often topped ratings in nearly every female demographic group and often held the No. 1 spot for teens.

Kraddick had matured. As a parent, he could identify with his adult audience. He started talking about his wife, Carol, and his daughter, Caroline, introducing a successful bit called “Bath Time With Caroline,” recording his toddler singing and playing in the tub. The audience loved it.

Naturally, there were still high jinks. One morning at 2 am, he called his friend Bert Weiss, his co-host at the time. “Bert, it’s Kidd,” Weiss remembers him saying. “John Tesh is in town. I have an idea. Yeah, it might be illegal.” Kraddick hired a limousine to take him to the airport to meet Tesh 10 minutes before his legitimate limo was scheduled to arrive and take him to an appearance on another morning show. They picked up Tesh and did an interview from the back of the car. Then they dropped him off at the other show. Tesh never knew what happened.

“My God, the dude had balls,” Weiss says. “He was fearless.”

One thing he wasn’t, though, was content, Weiss says. Little by little, Kraddick was achieving the life he had dreamed of: a hit show, fame, spectacular ratings, an enviable bank account. Yet none of it seem to make him happy.

“He could never just enjoy it,” says friend Lisa Mulcahy, who ran Bitboard. “You know, why does it always have to be better? It’s great right now. I would tell him, ‘Kidd, just back away a little and enjoy it.’ ”

Wilson pressed Kraddick to tell friends what was going on. Some had begun to wonder if he had a drug problem.

Despite his good-natured demeanor on air, he could also be impatient and hot-tempered. He would sometimes hurl his golf clubs at trees when he didn’t play well. His producers and technicians came to anticipate his moods and 2 am calls. He would arrive at the station to do the show with disheveled hair, having been up all night surfing the internet, watching late-night talk shows, thinking of new material. Around the station, they called him No Sleep Kidd. His pace could be hard on the people around him.

“It was awful,” Lindsay Lawler says with a laugh, recalling her time as Kraddick’s personal assistant. “You never knew when you were going to get a phone call with one of his crazy, grandiose ideas. And you would want to throw the phone at him. He was one of those guys who said, ‘Make it happen.’ There are plenty of people I have worked for, when they say, ‘Make it happen,’ you just want to give them the middle finger. But he could always make you say yes.”

Chris Cloutier worked as the show’s web engineer from 2005 to 2007. “There were times when I didn’t like him,” he says. “There were times when I thought he was an asshole, no question. There were times when it was just impossible to work for the guy. He chewed up a lot of people. But he was a madman genius, and I learned a lot from him.”

Kraddick rewarded the people who could keep up with him, though. One Christmas, he hosted an Oprah-style Favorite Things party, where he gave out everything from a set of pots and pans to new flat-screen televisions. Another Christmas, he invited his staff to a Walmart. When everyone arrived, from receptionists to co-hosts, he passed out envelopes, each stuffed with hundreds of dollars of cash, and told them they had 20 minutes to shop. Whatever they didn’t spend, they forfeited. Dozens of his employees raced through the Walmart, laughing and filling up shopping carts, with Kraddick using a megaphone to mark the time: “Four more minutes!”

“It was insane,” says a former co-host, Rich Shertenlieb. “Not only did he want to do something nice, but he wanted it to be like nothing you had ever done before.”

Kraddick was eventually able to leverage his success like very few radio personalties ever have. His show was picked up by Premiere Radio and broadcast nationally in 2001. Then, six years later, with his company YEA Networks, he took ownership of Kidd Kraddick in the Morning. He moved into his own studio in Irving and began syndicating the show himself, eventually reaching 74 markets.

Part of that success resulted from his hard work and immense talent. Part, though, came from his knack for assembling a cast of characters. Kraddick compared his show to reality television: “a group of people with no discernible talent getting together, and people actually watch them.” He found people who were naturally funny and came from different backgrounds. The diversity created conflict, which generated interesting discussions. The current group would not likely have been friends outside of that Irving studio: Kellie Rasberry, a conservative, white single mother from South Carolina; Big Al Mack, a swinging black bachelor from Dallas who was running a limo service when Kraddick discovered him; Jose Chavez, aka J-Si, a young, tender-hearted Hispanic who got married after joining the show; and Jenna Owens, a sultry twentysomething from the Midwest.

For four hours every weekday morning, they packed into a room to talk about their personal lives, with Kraddick at the center of every conversation. But he wasn’t sharing everything.

•••

Besides his friend Wilson, almost no one knew that Kraddick’s cancer diagnosis propelled him into a regimen of chemotherapy and radiation. He also began an aggressive round of stem-cell treatments that took a toll on his body. No matter how sick he was, though, Kraddick wasn’t going to miss Walt Disney World.

He had started Kidd’s Kids in 1991, raising hundreds of thousands of dollars, mostly on one day a year, in small donations from listeners, to send terminally and chronically ill children to the theme park. Wilson, as president of the charity, often accompanied Kraddick on the yearly trip. In 2010, as they arrived at the park, they were scheduled to meet some of the 250 mothers, fathers, and children to ride the Rock ’n’ Roller Coaster. But as soon as they stepped out of the van, Kraddick turned white.

“We’ve got a problem,” Kraddick said.

“He gets on the roller coaster with them, rides it, comes off, grabs me, and throws up in the bushes for 20 minutes,” Wilson says. “Then he would go over to the Tower of Terror, yuk it up with all the kids, have a great time, then come grab me again. We did that the entire trip.”

Wilson pressed Kraddick to tell close friends what was going on. Some had begun to wonder whether he had developed a drug problem. The speculation angered Wilson, but given how Kraddick looked, it made sense. Wilson argued that Kraddick should at least tell his daughter, Caroline. But the last few years had been difficult for Kraddick and his daughter. He had divorced her mother in 2008, after 21 years of marriage, and Kraddick didn’t want to put any additional strain on their relationship.

Then one day, Caroline found a stash of marijuana in Kraddick’s downtown condo. Caroline became upset and met Wilson for lunch.

“It’s not what you think,” he told her. “You should ask your father about it. But if you ask the question, you need to be prepared for the answer.”

The discovery forced Kraddick to tell Caroline about his cancer diagnosis. He had gotten the marijuana, he explained, to help with nausea.

Over time, Kraddick’s treatments seemed to work. Doctors declared him cancer-free and his prognosis, they said, was good. Even so, they warned of serious side effects, including organ damage, that could shorten his life. Kraddick finally told a few close friends about the cancer, feeling it wouldn’t be a burden anymore. He also started making plans to ensure that his radio show, and Kidd’s Kids, could survive after he was gone. He called Weiss, his friend and former co-host, who had left to start his own show in Atlanta. Weiss was deeply loyal to his mentor, and considered him a best friend.

“I’m not going to be doing this forever, Kraddick told him. “We need to start thinking of a hand-off plan.”

Kraddick didn’t tell Weiss about his illness. He just said that one day he’d like to retire and actually get some sleep. They began crafting a plan. First, Weiss transferred his own show to Kraddick’s network. Kraddick then helped guide Weiss through syndication, expanding his show to 20 cities. Kraddick planned to slowly introduce Weiss to his listeners, then finally name him as a replacement.

Over time, Kraddick’s hair grew back. He gained weight. He started working out, eating healthier. He felt he had been given a second chance, that he had been lucky. A new song came out by one of his favorite artists, Ben Folds, called “The Luckiest.” It quickly became a favorite.

I don’t get many things right the first time / In fact, I am told that a lot / Now I know all the wrong turns, the stumbles and falls brought me here … Now I see it every day / and I know that I am, I am, I am the luckiest.

One afternoon, Kraddick slipped into a chair at a tattoo parlor. He had never before wanted a tattoo, telling friends he couldn’t imagine a word or symbol that he would want to live with forever. Now he felt differently. He asked the artist to draw a musical staff on his left bicep, covered with the first four notes of the song. Beneath it, in cursive script, his tattoo read, “The Luckiest.”

Through 2011 and 2012, Kraddick’s health remained good. He met a woman, Lissi Mullen, and fell in love. With her, his friends believed, he seemed more content and peaceful than ever.

Then something puzzling happened. One of his teeth fell out. He snapped a picture and texted it to Wilson. What the hell?

Kraddick went to a dentist and learned that many of his teeth were loose. His jawbone was deteriorating, doctors said, and he’d likely lose them all. Kraddick wasn’t sure of the cause, but believed it was the stem-cell treatments.

One afternoon, Kraddick lay sedated on an operating table to have all his teeth removed and replaced with a temporary mold. The procedure was supposed to take four hours, but it stretched longer and longer. After 12 hours, Kraddick’s teeth were finally gone, and Kraddick, having been under longer than planned, had wet his pants. Wilson carried him to the car.

“Okay, this is officially the lowest point in our relationship,” Kraddick said. “We’ve got to find some new friends.”

Today, Wilson marvels at Kraddick’s demeanor. “I can’t express to you the horrific amount of pain he was in, and the post-op haze, and this horrific day he’s just had,” he said. “Yet he still wants to crack a joke. That made it easier on me. And I know that seeing me laugh, it made it easier on him.”

Weeks later, Kraddick returned to get his new implants. Another long procedure. At home, Kraddick was in pain and couldn’t eat solid food. The implants not only changed the way he looked but also how he sounded. He stayed home for a week to recover, looking in a mirror, trying to sound like his old self. He played tapes of himself and tried to mimic his voice. He called Wilson repeatedly.

“How about now? Do I sound right?”

“Nope,” Wilson replied.

“Damn!” he said, slamming down the phone.

•••

In June, Kraddick flew his cast to a mansion in Beverly Hills for an annual “family vacation.” Kraddick stood on a sunny portico, broadcasting live, when Dr. Phil McGraw, who lived down the street, strolled across the yard.

“Oh, my God! Dr. Phil!” Kraddick told his listeners in mock surprise. “What’s going on, man? Grab a mic.”

The men had known each other for about 20 years, first meeting at a Mavericks game, then becoming friends as their careers took off. For a time, McGraw had appeared on the show as a regular weekly guest. He was one of the few people Kraddick had told about his illness.

This day, McGraw played along with a bit about how neighbors were getting upset with the commotion caused by the show and its crew. McGraw refused to say which neighbor was leading the complaints. Working their way to the punch line, Kraddick finally got it out of McGraw: it was Justin Bieber.

After the show ended, Kraddick pulled McGraw aside and led him to his room. He pulled out a box and revealed a huge diamond ring.

“Now don’t throw me out the window,” Kraddick said. “But I’m getting married.” He quizzed McGraw about the ring. “What do you think of it? Is it big enough? Too big? Too flashy? Not flashy enough?”

“I told him, hell, for a bit, I’d marry him for that ring,” McGraw says.

The men played a round of golf at the Bel-Air Country Club later that afternoon. And, as inevitably happened, they found a shady spot under a tree. Kraddick had a lot on his mind that day. He told McGraw he planned to propose to his girlfriend later that week in Hawaii. He was worried about breaking the news to his daughter, who was then 23 years old. His girlfriend was 21 years his junior—at 32, closer in age to Caroline than to him. Then there was the divorce. Caroline was likely to have complicated feelings about another engagement. Even so, Kraddick felt he didn’t have time to waste.

“His attitude was, ‘Look, I don’t know how long I’ve got left, and I don’t want to waste a day of it,’ ” McGraw says. “ ‘I’m going to ask her to marry me, and we’re going to get married without any big delay, and I just want to do it in a way that is not inappropriate with my daughter.’ ” Kraddick didn’t seem morbid or panicked about his future, McGraw says. In fact, McGraw had never seen him happier.

From Hawaii, Kraddick sent McGraw updates by text. Mullen said yes. He called Caroline. All was well. He also sent a text to his daughter: You will always be my number one girl.

After he returned to Dallas in July, Kraddick went to see Caroline. Once a week, often on Tuesdays, he would drive to Fort Worth and take her to lunch. Usually their conversations were lighthearted, as they caught up on Caroline’s PR job and which recording artist Kraddick had just met. But on this afternoon, the mood was serious. Caroline asked about his engagement and wondered why he was keeping it so private. Why hadn’t he told his listeners? She didn’t know his fiancée well, had only met her a few times. But she worried for her father, always concerned whether the women he dated were after his money.

Then Kraddick did something that surprised Caroline. He apologized. He said he was sorry for talking about her personal life on the radio for all those years, for getting her into trouble with friends by revealing details on air that, to a teenager, had been mortifying. His formula for radio—keeping it real, letting listeners into his own life—had meant that everyone around him became material for his show. Any personal moment might be spun into a story for his listeners. Sometimes, in the pressure to fill four hours of air time, he couldn’t resist telling the stories, no matter the cost to those around him.

“That was the first time he had said, ‘I’m sorry for subjecting you to all of this,’ ” Caroline says. “I was a little taken aback when he said it.”

Kraddick knew his daughter had decided to go to school in Oklahoma City in part because he wasn’t on the radio there, and no one would know she was Kidd Kraddick’s daughter. She now feels a little silly complaining about her life. There were so many perks: the private-school education, the backstage passes.

They hugged, and then he drove away. It was the last time she would see her father.

That same week, Kraddick met Wilson in Arlington for a Rangers game. He brought along his fiancée. Wilson was disturbed by his friend’s appearance. He looked sick again, pale and thin.

“You look like crap,” Wilson told him. “You’re not taking your medicine, are you?”

Kraddick admitted he had stopped taking the pills that helped keep the cancer in remission. They made him feel bad.

“Okay, what’s the plan?” Wilson asked.

Kraddick looked at him. “I don’t know,” he said.

Wilson wondered if Kraddick thought he was getting sick again and perhaps didn’t want to know what was wrong.

•••

At the end of that week in July, on a Friday afternoon, Kraddick and his staff flew to New Orleans for a Kidd’s Kids charity golf tournament. That night, part of the group ate at the Acme Oyster House and stepped out into the street at about 10 pm. That was when Kraddick saw the man selling DVDs. After waiting for Kraddick, the group moved into the crowds of Bourbon Street. People began to recognize Chavez.

“J-Si! J-Si!” they shouted across the street.

It amused Chavez that he was the first to be recognized, because he knew it would irritate Kraddick.

Chavez felt Kraddick had been responsible for many good things in his life. Chavez had only recently stopped living in his pickup truck, a Mazda single cab with flames on the side, when Kraddick hired him at 23 years old. Not only had Kraddick taught him the ropes of morning radio, but he’d also become a friend and a father figure. When Chavez bought an engagement ring, he rushed to get Kraddick’s approval.

“Dang it, J-Si!” Kraddick said. “Where did you buy this piece of crap?”

Chavez explained he had bought it on eBay. Kraddick took him to see his personal jeweler, where Chavez was shown a sparkling diamond. He figured it was more than he could afford, but the jeweler said he would cut him a deal. Chavez believes Kraddick quietly paid the difference.

On that night in New Orleans, fans began to recognize Kraddick, too, something he loved, and he always stopped to talk and take photographs. He noticed two women walking by in bikinis and asked about their attire. They had decided to get into shape for their 42nd birthdays, and they were celebrating. Kraddick bought them a couple of giant margaritas.

As the clock swept past 2 am, the group headed back to the W New Orleans hotel. Sitting in the backseat of a taxi, Kraddick and Chavez rapped Eminem songs the whole way, making the others laugh as they flubbed the lyrics. While Chavez and most of the others went up to their rooms, Kraddick went to the casino at Harrah’s New Orleans, where he was staying. He loved to play craps. Several times, his friends say, after winning big, he had gone out into Bourbon Street in the early morning hours, passing out hundred-dollar bills.

“RIP Kidd Kraddick. You were an amazing man and a friend. You are already missed.

Mark Cuban, announcing Kraddick’s death via Twitter

The next morning, Kraddick met his cast in the W New Orleans hotel. He was wearing shorts and a tight blue shirt. “Dude, you look like a GQ model golfer right now,” Chavez joked. Kraddick did an exaggerated model’s strut in the hotel lobby, his lips pursed like a duck.

They headed to the Timberlane Country Club in a bus. There, they greeted dozens of families, and Kraddick went off to hit a few balls on the range. But before long, he stepped away, saying he didn’t feel well. It was a muggy, sweltering afternoon. Everyone assumed he was dehydrated.

Kraddick stepped onto the bus with his good friend and company CEO, George Laughlin. He took a sip of water, then dropped the bottle. Kraddick collapsed on the floor as Laughlin rushed toward him. He began performing CPR. The bus driver raced to a hospital several miles away, thinking it would be quicker than waiting for an ambulance.

His co-hosts arrived at the hospital, and were led into a small room. A doctor told them they had tried everything, but they had not been able to revive Kraddick. He asked if they had any questions.

Rasberry had one. “Did he suffer?”

“No,” the doctor said. “It happened so quickly, he likely didn’t even have time to be afraid.”

The doctor asked if the crew wanted to say goodbye to Kraddick. They looked at each other, nodded, and filed into the room. Kraddick lay on a hospital bed, his eyes closed.

Chavez leaned down and touched Kraddick’s forehead. “Thank you,” he told Kraddick. “I love you.”

Standing there, they all had the same thought, the desperate hope, that Kraddick would jump up and reveal it was all a joke. Just the week before, he’d done a “deathbed confessions” bit on the show. With sound effects of a ventilator and a heart monitor in the background, he had told J-Si that he liked his hot wife. Then he confessed that he was his real father. He told Rasberry he was glad they had never hooked up because the reality would not have measured up to the fantasy he had in his head. Now, in New Orleans, it seemed surreal, for the man who had been so noisy, so full of jokes and manic energy, to be lying there, motionless. It became unbearable to be in the room, but no one was ready to leave.

After they stepped out of the room, Kraddick’s friends made a promise not to tell anyone until they could reach Caroline. But a woman from the golf tournament had been taken to the hospital to be treated for heat exhaustion. She learned what had happened, and word slowly began to spread, across New Orleans, west to Dallas, and across the country.

By the time the crew’s plane landed in Dallas, Mark Cuban had announced it to the world on Twitter at 9:32 pm.

RIP Kidd Kraddick. You were an amazing man and a friend. You are already missed.

Evening anchors delivered the news on national broadcasts, and newspapers announced Kraddick’s death on their front pages across the country. “The coverage of his death was shocking to me,” says Rusty Humphries, a Phoenix radio host and former Kraddick co-host. “ How do I say this without sounding horrible? In a way, it was his crowning achievement. Mark Cuban was the guy who announced it. Harry Styles tweeted about it. People were crying in the streets. I mean, when was the last time you heard about a DJ dying? Never.”

It turned out that the cancer had not been the primary cause of Kraddick’s death. An autopsy revealed that he had severe blockages in his heart. It’s not clear whether his cancer treatments had any impact on his heart condition. A toxicology test showed that his blood contained traces of amphetamine, which is present in some attention-deficit medications. Kraddick frequently referred to his having ADD. Also in his system were marijuana, ibuprofen, and nicotine, but no alcohol or other drugs. None of those substances was considered a contributing factor in his death.

•••

Three weeks after Kraddick’s death, Caroline sat on a gold fabric chair, on the eighth floor of the Ritz-Carlton, in a two-bedroom suite with views of the Dallas skyline. A few blocks away, at the American Airlines Center, hundreds of friends and fans had already gathered. Caroline had hosted a private Catholic funeral at a sanctuary in Arlington, and Wilson had gathered their best friends at Dallas National Golf Club, where they played a round and told their favorite stories about him. But there needed to be a public memorial as well. Thousands of listeners felt like they had lost a friend.

In the hotel suite, Caroline wore a pink t-shirt and gray sweatpants, her shoulder-length brown hair still damp from a shower, as she sat with her eyes closed, drinking whiskey. Several of her childhood best friends were there, talking and telling stories about her father. A woman from the hotel spa circled her with a blow dryer and makeup brushes, preparing Caroline for an appearance on the stage. A flowing gown hung on the bedroom door, purchased earlier that week with the help of a personal shopper at Neiman Marcus.

All the planning had helped Caroline to keep moving forward, to stop her from thinking about all the words left unsaid, all the moments they would not share: her dad walking her down the aisle, or getting to meet his grandchildren.

Caroline was now, at 23 years old, the sole heiress of her father’s multimillion-dollar estate. She was also in charge of his radio empire, with its 19 employees, and his charity. Although Kraddick had been planning for his eventual death, he had run out of time. How would Kidd Kraddick in the Morning continue without Kidd Kraddick?

Because Caroline was so young, her mother, Carol, stepped in to help manage the business affairs of her ex-husband’s company. The move didn’t please everyone. Some felt Kraddick wouldn’t want her having a hand in his business. But the couple had been married for 21 years, and Kraddick had credited Carol with pushing him early on in his career.

Then there was the matter of the fiancée, Mullen, living in Kraddick’s 31st-floor condo at the W. What would become of her? She was devastated by Kraddick’s death. (She declined to be interviewed for this story, saying she was not yet ready to talk about Kraddick.) The condominium now belonged to Caroline. Mullen was given several weeks to move out.

Tensions rose. Lawyers got involved. An attorney working for Kraddick’s estate used a subpoena to try to get video footage from cameras outside of Kraddick’s condo and storage unit, wanting to know exactly what had been taken out of the penthouse since his death. The women were trying to resolve their disputes quietly, but most people around the company knew what was happening, and some began taking sides with either his fiancée or his daughter.

But on this summer night, all that was still to come. In her Ritz suite, Caroline began to hum, warming her voice to sing, as she clicked across the marble foyer in her heels, her teary eyes covered by large Dior sunglasses. She glided into the elevator and headed down, down, down, out into the sunlight, out into a crowd growing larger by the minute.

It was time to say goodbye to Kidd.

Correction: An earlier version of this story mistakenly stated that Tom Hicks and Mike Modano are members of Dallas National Golf Club.