Two guys approached him with pistols and demanded his money and the keys to his truck. With his hands in the air, he sized up which man seemed most confident with his gun.

Kyle knew what confidence with a gun looked like. He was the deadliest sniper in American history. He had at least 160 confirmed kills by the Pentagon’s count, but by his own count—and the accounts of his Navy SEAL teammates—the number was closer to twice that. In his four tours of duty in Iraq, Kyle earned two Silver Stars and five Bronze Stars with Valor. He survived six IED attacks, three gunshot wounds, two helicopter crashes, and more surgeries than he could remember. He was known among his SEAL brethren as The Legend and to his enemies as al-Shaitan, “the devil.”

He told the robbers that he just needed to reach back into the truck to get the keys. He turned around and reached under his winter coat instead, into his waistband. With his right hand, he grabbed his Colt 1911. He fired two shots under his left armpit, hitting the first man twice in the chest. Then he turned slightly and fired two more times, hitting the second man twice in the chest. Both men fell dead.

Kyle leaned on his truck and waited for the police.

When they arrived, they detained him while they ran his driver’s license. But instead of his name, address, and date of birth, what came up was a phone number at the Department of Defense. At the other end of the line was someone who explained that the police were in the presence of one of the most skilled fighters in U.S. military history. When they reviewed the surveillance footage, the officers found the incident had happened just as Kyle had described it. They were very understanding, and they didn’t want to drag a just-home, highly decorated veteran into a messy legal situation.

Kyle wasn’t unnerved or bothered. Quite the opposite. He’d been feeling depressed since he left the service, struggling to adjust to civilian life. This was an exciting reminder of the action he missed.

That night, talking on the phone to his wife, Taya, who was in the process of moving with their kids from California, he was a good husband. He asked how her day was. The way some people tell it, he got caught up in their conversation, and only right before they hung up did he remember his big news of the day: “Oh, yeah, I shot two guys trying to steal my truck today.”

A brief description of the incident appeared in fellow SEAL Marcus Luttrell’s 2012 book Service: a Navy SEAL at War— but not Kyle’s own best-seller, American Sniper—and there are mentions of it in various forums deep in the corners of the internet. Before Kyle’s murder at the hands of a fellow veteran in February, I asked him about that story during an interview in his office last year, as part of what was supposed to be an extended, in-depth magazine story about his service and how hard he worked to adjust back to this world—to become the great husband and father and Christian he’d always wanted to be.

He didn’t want to get into specifics about the gas station shooting, but I left that day believing it had happened.

• • •

By the official count, Chris Kyle racked up 160 confirmed kills as a Navy sniper. He pegged the actual number as twice that.

The offices of Craft International, the defense contractor where Chris Kyle was president until his death, were immaculate. You needed one of the broad-chested security guards from downstairs as an escort just to get to that floor of the building. Sitting under thick glass in the lobby, there was an exceptionally rare, original English translation of Galileo’s Dialogue (circa 1661). A conference room held a safe full of gigantic guns—guns illegal to own without a Department of Defense contract.

At 38, Kyle was a large man, 6-foot-2, 230 pounds, and the muscles in his neck and shoulders and forearms made him seem even bigger, like a scruffy-bearded giant. When he greeted me with a direct look in the eye and a firm handshake, his huge bear paw enveloped my hand. That day he had on boots, jeans, a black t-shirt, and a baseball cap. It’s the same thing he wore most days he came to the office, or when he watched his daughter’s ballet recitals, or during television interviews with Conan O’Brien or Bill O’Reilly.

This was one of the rare chances when he’d have a few hours to talk. Over the next three days, he would be teaching a sniper course to the Dallas SWAT teams and he had three book signings, one at a hospital in Tyler (for a terminal cancer patient whose doctor reached out to him), one at Ray’s Sporting Goods in Dallas, and one at the VA in Fort Worth. He’d also have to fly down to Austin for a shooting event Craft was putting on for Speaker of the House John Boehner and several other congressmen.

“We are not doing this for free,” he said, anticipating a question. “We accept Republicans and Democrats alike, as long as the money is good.”

A few weeks later, he would have to cancel a weekend meeting because he was invited to hang out with George W. Bush. “Sorry,” he said, when asked if anyone else might be able to join. “Not even my wife’s allowed to come.”

He loved the Dallas Cowboys and the University of Texas Longhorns. He loved going to the Alamo, looking at historic artifacts. The license plate on his truck had a picture of the flag used during the Texas Revolution, with a cannon, a star, and the words COME AND TAKE IT. Being in the military forced him to move a lot, and neither of his children was born in Texas. But for each birth, he had family send a box of dirt from home—so the first ground his kids’ feet touched would be Texas soil.

He was outspoken on a lot of issues. He believed strongly in the Second Amendment, politely decrying the “incredible stupidity” of gun control laws anytime he was asked. He said he was hesitant to see the movie Zero Dark Thirty because he’d heard that it was a lot of propaganda for the Obama administration. Once, he posted to his tens of thousands of Facebook fans: “If you don’t like what I have to say or post, you forget one thing, I don’t give a shit what you think. LOL.”

He didn’t worry about sounding politically incorrect. The Craft International company slogan, emblazoned around the Punisher skull on the logo: “Despite what your momma told you, violence does solve problems.”

His views were nuanced, though. “If you hate the war, that’s fine,” he told me. “But you should still support the troops. They don’t get to pick where they’re deployed. They just gave the American people a blank check for anything up to and including the value of their lives, and the least everyone else can do is be thankful. Buy them dinner. Mow their yard. Bake them cookies.”

“The best way to describe Chris,” his wife, Taya, says, “is extremely multifaceted.”

He was a brutal warrior but a gentle father and husband. He was a patient instructor, and he was a persistent, sophomoric jokester. If he had access to your Facebook account, he might announce to all your friends and family that you’re gay and finally coming out of the closet. If he wanted to make you squirm, he might get hold of your phone and scroll through your photos threatening to see if you kept naked pictures of your girlfriend.

Kyle liked when people thought of him as a dumb hillbilly, but he had a remarkable ability to retain information, whether it was a mission briefing, the details of a business meeting, or his encyclopedic knowledge of his own hero, Vietnam-era Marine sniper Carlos Hathcock. While on the sniper rifle, Kyle had to do complicated math, accounting for wind speed, the spin of a bullet, and the curvature and rotation of the Earth—and he had to do it quickly, under the most intense pressure imaginable. Those were the moments when he thrived.

The most common question he was asked was easy to answer. He said he never regretted any of his kills, which weren’t all men.

“I regret the people I couldn’t kill before they got to my boys,” he said. That’s how he referred to the men and women he served with, across the branches: “my boys.”

He said he didn’t enjoy killing, but he did like protecting Americans and allies and civilians. He was the angel of death, sprawled flat atop a roof, his University of Texas Longhorns ball cap turned backward as he picked off enemy targets one by one before they could hurt his boys. He was the guardian, assigned to watch over open-air street markets and elections, the places that might make good marks for insurgent terrorists.

“You don’t think of the people you kill as people,” he said. “They’re just targets. You can’t think of them as people with families and jobs. They rule by putting terror in the hearts of innocent people. The things they would do—beheadings, dragging Americans through the streets alive, the things they would do to little boys and women just to keep them terrified and quiet—” He paused for a moment and slowed down. “That part is easy. I definitely don’t have any regrets about that.”

He said he didn’t feel like a hero. “I’m just a regular guy,” he said. “I just did a job. I was in some badass situations, but it wasn’t just me. My teammates made it possible.” He wasn’t the best sniper in the SEALs teams, he said. “I’m probably middle of the pack. I was just in the right spots at the right times.”

The way he saw it, the most difficult thing he ever did was getting out of the Navy.

“I left knowing the guy who replaced me,” he said. “If he dies, or if he messes up and other people die, that’s on me. You really feel like you’re letting down these guys you’ve gone through hell with.”

Kyle said he didn’t feel like a hero. “I’m just a regular guy,” he said.

The hardest part? “Missing my boys. Missing being around them in the action. That’s your whole life, every day for years. I hate to say it, but when you’re back and you’re just walking around a mall or something, you feel like a pussy.” It nagged at him. “You hear someone whining about something at a stoplight, and it’s like, ‘Man, three weeks ago I was getting shot at, and you’re complaining about—I don’t even care what.’ ”

There was also the struggle to readjust to his family life. “When I got out, I realized I barely knew my kids,” he said. “I barely knew my wife. In the three years before I got out, I spent a total of six months at home. It’s hard to go from God, Country, Family to God, Family, Country.”

But three years after he left the SEALs, he had a job he liked. He could do (mildly) badass things: shoot big guns, detonate an occasional string of explosives, be around a lot of other former special-operations types. His marriage was finally back in a good place. He had a book on the best-seller list. And he had the chance to help veterans through a number of charities.

“A lot of these guys just miss being around their boys, too,” he said. “They need guys who speak their speak. They don’t need to be treated like they’re special.”

He’d often take vets out to the gun range. Being around people who understood what they’d been through, being able to relax and shoot off some rounds, it was a little like group therapy.

With his family, and with training people, helping people, he had found a new purpose. Chris Kyle could do anything if he had a purpose. He’d been like that since he was a little boy.

• • •

In high school in Midlothian, he played football and baseball. He showed cows through the FFA. He and his buddies cruised for girls in nearby Waxahachie. He also liked to fight. His father warned him never to start a fight. Kyle said he lived by that code “most of the time.” He found that if he was sticking up for his friends, or for kids who couldn’t defend themselves, he got to fight and he got to be the good guy at the same time. Once he felt like he was standing up for something right, he would never back down.

Bryan Rury was a close friend of Kyle’s in high school. Rury was much smaller than his friend, but it seemed they were always standing next to each other. “I think Chris liked looking like a giant,” Rury says.

One time, there was a new kid in school who was trying to make a name for himself by picking on Rury. Kyle came into class one day to find Rury quiet, upset. “He asked me what was wrong, and I wouldn’t tell him,” Rury says. “But he figured it out on his own pretty fast.”

Kyle went over to the new kid’s desk and, in his not-so-subtle, Chris Kyle way, told him he better leave his friend alone. Or else. The kid stood up from his desk, and they went at it. Kyle almost never started the fight, his friends say, but he always ended it. “As they were taking him off to the principal’s office, I just remember him flashing me that giant smile of his,” Rury says.

After high school, he went to Tarleton State for two years, mostly to postpone the responsibilities of adulthood. He spent more time drinking than studying, and soon he decided he’d rather be working on a ranch full-time. But he knew his future was in the military—in the Marines, he thought, until a Navy recruiter told him about all the cool things he could potentially do as a SEAL—and he figured he shouldn’t waste any more time.

Kyle breezed through the Navy’s basic training. He only made it through BUD/S (Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL) training by way of sheer resolve. He told stories about lying there on the beach, his arms linked with his friends’, their heads hovering above the frigid rising tide. He knew if he got up and rang the bell—if he quit—he could get hot coffee and a doughnut. The uncontrollable shivering—they called it “jackhammering”—lasted for hours, but he never wanted to stop. He joked that he was just lazy, that if the bell had only been a little closer, maybe his entire life would have been different. But the truth is, nothing could have kept him from his dream.

“He had more willpower than anyone I’ve ever met,” Taya says. “If he cared about something, he just wouldn’t ever quit. You can’t fail at something if you just never quit.”

Taya met Kyle in a bar in San Diego, just after he finished BUD/S. When she asked what he did—she suspected from the muscles and the swagger that he was in the military—he told her he drove an ice cream truck. She figured he’d be arrogant but was surprised to find him idealistic instead. But she was still skeptical. Taya’s sister had divorced a guy who was trying to become a SEAL, and she’d specifically said she could never marry someone like that.

But Kyle turned out to be quite sensitive. He was able to read her better than anyone she’d known. Even when she thought she was keeping something hidden behind a good facade, he could always see through it. That kept them from needing to talk about their emotions or constantly reassess their relationship. They got married shortly before he shipped out to Iraq for the first time.

• • •

It takes years to earn enough trust to be a SEAL sniper. Even after sniper school, Kyle had to prove himself again and again in the field, in the pressure of battle. He served other missions before Afghanistan and Iraq, in places he couldn’t discuss because the operations were classified.

As he would eventually describe in American Sniper, his first kill on the sniper rifle came in late March 2003, in Nasiriya, Iraq. It wasn’t long after the initial invasion, and his platoon—“Charlie” of SEAL Team 3—had taken a building earlier that day so they could provide overwatch for a unit of Marines thundering down the road. He was holding a bolt-action .300 Winchester Magnum that belonged to his platoon chief. He saw a woman about 50 yards away. As the Marines got closer, the woman pulled a grenade. Hollywood might have you believe that snipers aim for the head—“one shot, one kill”—but effective snipers aim for the middle of the chest, for center mass.

Kyle pulled the trigger twice.

“The public is soft,” he used to say. “They have no idea.” Because of that softness, he had to have that story, and others, cleared by the Department of Defense before he could include them in his book.

He wanted outsiders to know exactly what kind of evil the troops have had to deal with. But he understood why the Pentagon wouldn’t want to give America’s enemies any new propaganda. He knew the public didn’t want to hear about the brutal realities of war.

Kyle served four tours of duty in Iraq, participating in every major campaign of the war. He was on the ground for the initial invasion in 2003. He was in Fallujah in 2004. He went back, to Ramadi in 2006, and then again, to Baghdad in 2008, where he was called in to secure the Green Zone by going into Sadr City.

Most of his platoon was in the Pacific theater before the 2004 deployment. Kyle was sent early to assist Marines clearing insurgents in Fallujah. Tales of his success in combat trickled back to his team. He was originally supposed to watch over the American forces perched at a safe distance, but he thought he could provide more protection if he was on the street, going house to house with his boys. During one firefight, it was reported that Kyle ran through a hail of bullets to pull a wounded Marine to safety. His teammates, hearing these stories, started sarcastically referring to him as The Legend.

Those stories of bravery in battle proliferated on his third deployment. A younger SEAL was with Kyle at the top of a building in Ramadi when they came under heavy fire. The younger SEAL, who is still active in the teams and can’t be named, dropped to the ground and hid behind an interior wall. When he finally looked up, he saw Kyle standing there, glued to his weapon, covering his field of fire, calling out enemy positions as he engaged.

Kyle said the combat was the worst on his last deployment, to Sadr City in 2008. The enemy was better armed than before. Now it seemed like every time there was an attack, there were rocket-propelled grenades and fights that went on for days. This was also the deployment that produced Kyle’s longest confirmed kill.

He was on the second floor of a house on the edge of a village. With the scope of his .338 Lapua, he started scanning out farther into the distance, to the edge of the next village, a mile away. He saw a figure on the roof of a one-story building. The figure didn’t seem to be doing much, and at the moment he didn’t appear to have a weapon. But later that day, as an Army convoy approached, Kyle checked again and saw the man holding what looked like an RPG. At that distance, Kyle could only estimate his calculations.

He pulled the trigger and watched through his scope as the Iraqi, 2,100 yards away, fell off the roof. It was the world’s eighth-longest confirmed kill shot by a sniper. Later, Kyle called it a “really, really lucky shot.”

—

Chris Kyle didn’t fit the stereotype of the sullen, lone wolf sniper. In many ways, he was far from the model serviceman. While he always kept his weapons clean, the same was not true of his living space. The way some SEALs tell it, after one deployment, his room was in such a disgusting condition that it took two days to clean. There were six months worth of spent sunflower seed shells he had spit around the bed.

He was seldom seen in anything remotely resembling a military uniform. His teammates remember him painting the Punisher skull on his body armor, helmets, and even his guns. He also cut the sleeves off his shirts. He wore civilian hunting shoes instead of combat boots. Eschewing the protection of Kevlar headgear, he wore his old Longhorns baseball cap. He told people he wore that hat so that the enemy knew Texas was represented, that “Texans shoot straight.”

Kyle heard people call snipers cowards. He would point out that snipers, especially in urban warfare, decrease the number of civilian casualties. Plus, he said, “I will reach out and get you however I can if you’re threatening American lives.”

He terrorized his enemies in true folkhero fashion. In 2006, intelligence officers reported there was a $20,000 bounty on his head. Later it went up to $80,000. He joked that he was afraid to go home at one point. “I was worried my wife might turn me in,” he said.

Taya has been asked often over the years how she reconciles the two Chris Kyles: the trained killer and the loving husband and father—the man who rolled around on the floor with his kids and planned vacations to historical sites and called from wherever he could. (Once he thought his phone was off and she ended up overhearing a firefight.) She always worried about him, but understanding how he could do what he did was never hard.

“Chris was out there fighting for his brothers because he loved them,” she says. “He wanted to protect them and make sure they all got to go home to their families.”

He never cared to talk much about the number of confirmed kills he had. It’s likely considerably higher than what the Pentagon has released, but certain records could remain classified for decades. Besides, while the number garners a lot of attention, it doesn’t tell Kyle’s story. He told people he wished he could somehow calculate the number of people he had saved. “That’s the number I’d care about,” he said. “I’d put that everywhere.”

While seeing his enemies die never gave him much pause, losing his friends devastated him. When fellow Team 3 Charlie platoon member Marc Lee died in August of 2006—the first SEAL to die in the Iraq war—Kyle was inconsolable. All of Lee’s teammates prepared remarks for a memorial service in Ramadi. Kyle wrote out a speech, but when it came time to give it, he couldn’t talk. Every time he tried, he broke down, sobbing.

“He came up and hugged me afterwards,” an active SEAL says. “He apologized. He said, ‘I’m sorry. I wanted to, but I just couldn’t do it.’ ”

It was at a similar event later that year— a wake for fallen SEAL Michael Monsoor, who was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for throwing himself on a grenade to save the lives of fellow SEALs—when Kyle had his now-infamous confrontation with former Minnesota governor Jesse Ventura.

They were in a bar popular among SEALs in Coronado, California. Kyle said that Ventura, a former SEAL himself, was in town for an unrelated event and stopped by the wake. According to Kyle, Ventura disrespected the troops, saying something to the effect of, “You guys deserve to lose a few.” That was enough. Kyle punched him and left the bar. Ventura denied the entire incident and later filed a lawsuit against Kyle. But two other former SEALs, friends of Kyle’s, told me they were there that night, and it happened just the way Kyle said it did.

• • •

“When I first got out, I had a lot of resentment,” he said. “I felt like she knew who I was when she met me. She knew I was a warrior. That was all I’d ever wanted to do.” He started drinking a lot. He stopped working out. He didn’t want to leave the house or make his usual jokes. He missed the rush of combat, the way being at war sets your priorities straight. He missed knowing that what he was doing mattered. More than anything, though, he missed his brothers in the SEALs. He wrote to them and called them. He told people it felt like a daze.

But when he wrote to his closest friends, he talked about the one benefit of being out of the Navy. In all those years at war, he’d had almost no time with his two children. And in his time out, he discovered there was something he liked even more than being a cowboy or valiant sniper.

“He loved being a dad,” Taya says. She noticed he could be rough and playful with their son and sweet and gentle with their daughter. “A lot of fathers play with their kids, but he was always on the floor with them, rolling around, making everyone giggle.”

Kyle began to feel better. He got sick of feeling sorry for himself. He didn’t want a divorce. He started working out again— “getting my mind right,” he called it.

When he met other vets who were feeling down, he told them they should try working out more, too. But many of them, especially the wounded men with missing limbs or prominent burns, explained that people stared too much. Gyms made them uncomfortable. That’s how he got the idea to put gym equipment in the homes of veterans. When he approached FITCO, the company that provides exercise machines for facilities all over the country, and asked for any used equipment, they said no. They donated new equipment instead and helped fund a nonprofit dedicated to Kyle’s mission.

“With helping people,” Taya says, “Chris found his new purpose.”

She watched him use the same willpower that had carried him through SEAL training and all those impossible missions, but now he was trying to become a better man. He started coaching his son’s tee-ball team and taking his daughter to dance practice. He’d always liked hunting, but he hated fishing. Still, when he learned that his son liked to fish, he dedicated himself to becoming a great fisherman, so they could bond the way he did with his own dad.

Kyle took the family to football games at Cowboys Stadium. He took them to church. Unless he was hanging out of a helicopter with a gun doing overwatch, he hated heights. But when his kids wanted to go, he took them to Six Flags to ride the roller coasters and to the State Fair for the Ferris wheel. His black truck became a familiar sight driving around Midlothian.

He started collecting replicas of Old West guns, like the ones the cowboys used in movies when he was a boy. Taya would find him practicing his quick draw and gun twirling skills. Sometimes they would sit on the couch, watching TV, and he would twirl an unloaded six-shooter around his finger. If she saw someone on the screen that she didn’t like, she would jokingly ask, “Can you shoot that guy?”

He’d point the pistol at the TV and pretend to fire.

“Got him, babe.”

J. Kyle Bass is a hedge fund manager in Dallas, the founder of Hayman Capital Management. He was featured prominently in the Michael Lewis book, Boomerang: Travels in the New Third World, which documented both his keen financial mind and his fantastically opulent lifestyle. A few years ago, Bass was feeling overweight and out of shape. A former college athlete, he wanted something intense, so he found a Navy SEAL reserve commander in California, a man who gets prospective SEALs prepared for BUD/S, and asked if they could tailor a short program for him. Bass found that he really liked hanging out with the future and active SEALs. He said if they knew any SEALs coming back to Texas, he’d love to meet them.

That’s how Bass met Chris Kyle. Bass was building a new house at the time, and he offered to fly in Kyle and pay him for some security consulting.

“I was just trying to come up with anything to help the guy out,” Bass says. “I was looking for ways to try and help him make this transition back into the real world.”

Bass invited Kyle to live at his house with him while Taya finished selling their place in San Diego. He introduced Kyle to as many “big money” people as he could. And the wealthy men were enthralled by Chris Kyle. They loved being around the legend. They loved hearing his stories and invited him to go hunting on their ranches. Bass would hold an economic summit every year at his ranch in East Texas. He would kick off the festivities by introducing his sniper friends.

“I’d have Chris and other SEALs come out and do exhibition shoots,” Bass says. “They would take 600-yard shots at binary explosives, so when they hit them it’s this giant explosion that shakes the ground.” He smiles as he tells the story. “For all the people that manage money all over the world and on Wall Street to come to Texas and see a Navy SEAL sniper shoot a bomb, it’s about as cool as it gets.”

Bass and some business associates also helped start Craft International. They put the Craft offices on the same floor as Hayman, so the finance folks and the defense contractors often crossed paths. Despite working in a plush office building in downtown Dallas, Kyle didn’t change much. Even if he saw an important meeting, it wouldn’t stop him from grinning and flipping off an entire room of people.

The idea was to market Kyle’s skills. He could help train troops (a lot of military training is done by third-party contractors), and police officers, and wealthy businessmen who would pay top dollar for hands-on instruction from an elite warrior like Chris Kyle. He could take people out to Rough Creek Lodge in Glen Rose, a luxury resort with an extended shooting range. It’s the same place he would take buddies and wounded vets when they were feeling down and needed to unwind.

• • •

Kyle insisted that he never had any intention of writing of a book. He was told there were already other writers working on it, and he figured if it was going to happen anyway, he might as well participate. He wanted to give credit where he felt it was due.

He and Taya were flown to New York in the middle of winter, to meet writer Jim DeFelice and begin pouring out their story. The interviews were exhausting.

In 2006, intelligence officers reported there was a $20,000 bounty on his head. Later it went up to $80,000.

“He was not naturally loquacious,” DeFelice says. “Nor did he particularly like to talk about himself. When we first started working together, telling me what happened in the war put an enormous strain on him. He was reliving battles in great detail for the first time since he’d gotten out of the service. He could have been killed in any number of the situations he’d been in. That’s a reality that can be difficult to comprehend at the time, and even harder to understand later on.”

Kyle did find time at one point for a snowball fight with DeFelice’s 13-year-old son. The war hero claimed he’d had plenty of experience in snow, but on this day, the boy got the better of him. Kyle came running in and grabbed a beer.

“Okay, kid,” Kyle told him. “Now you can say you beat a Navy SEAL in a snowball fight.”

Kyle decided not to take a dime from American Sniper. As it became a best-seller, his share amounted to more than $1.5 million. He gave two-thirds to the families of fallen teammates and the rest to a charity that helped wounded veterans. It was something he and Taya discussed a lot.

“I would ask him, ‘How much is enough? Where does your family fit in?’ ” she says.

“But I understood.”

When the book came out, everyone wanted to interview him. He was on late-night talk shows, cable news, and radio. He did a number of reality TV shows related to shooting. (He rarely took much money from the appearances.) He always went on with a ball cap on his head and a wad of tobacco in his mouth.

He had 1,200 people at his first public book signing. It was similar in every town. He preferred to stand for the length of the book signings. “If y’all are standing, I can stand,” he said. He would wait until he signed every book he was asked to, even if it took hours. It often did, because he wanted to take a moment to talk with each person. He tried to personalize each book. He’d pose for photos, one after another.

As he became more famous, more people wanted to spend time with him. More politicians wanted to go shooting with him. At one point, he was at a range with Governor Rick Perry. Perry was about to shoot the sniper rifle and asked Kyle if he had an extra pad to put on the cement before he lay down. Kyle replied with a mock-serious tone.

“You know, Governor,” he said, “Ann Richards was out here not too far back, and she didn’t need a pad at all.”

A good friend once introduced him to the movie star Natalie Portman. He asked her what she did for a living. And, as the story goes, she liked him even more after that.

Then there is this story: Kyle had been invited to a luxury suite at a UT football game and decided to take a heartbroken buddy of his, a Dallas police officer who had recently caught his girlfriend making out with another guy. They were in the suite for a few hours, talking, drinking, when a former UT football star happened to walk in. At some point, Kyle realized that this former star was also the guy who had kissed his friend’s girlfriend.

Kyle’s friend knew what was coming. He begged him not to, but it was in vain.

“It’s man law,” Kyle said.

He had a party trick he liked to perform, a sleeper hold that would render a man unconscious in seconds. Kyle called it a “hug.” People would dare him to do it to them, saying they wouldn’t go down.

Sure enough, Kyle approached the former star and gave him a “hug” right there in the suite. As women were shrieking and wondering if the former UT great was dead, Kyle kept the hold for just a little longer than normal, causing the man to lose control of his bowels as he passed out.

It wasn’t just his friends he took care of. People wrote to him from all over the world, asking for favors or for his time, especially after he started appearing on TV. He did his best to accommodate every request he could, even when Taya was worried he was spreading himself too thin.

“He was so trusting,” she says. “He didn’t let himself worry about much.”

• • •

Jodi Rough, a teacher’s aide at anelementary school close to Kyle’s home, had a son, a former Marine, who needed help. She reached out to Kyle because she knew his history of caring for veterans. Kyle told people he and his friend, Chad Littlefield, were going to take the kid out to blow off some steam.

Littlefield was a quiet buddy Kyle had come to count on over the last few years. They worked out and went hunting together. He had come over a few nights earlier to have Kyle adjust the scope of his rifle. Kyle invited Littlefield to come with him to Rough Creek. They were going to take Jodi Routh’s son shooting. Littlefield had accompanied Kyle on similar trips dozens of times.

They were in Kyle’s big black truck when they showed up in the Dallas suburb of Lancaster, at the home Eddie Ray Routh shared with his parents. He was a stringy, scraggly 25-year-old. He’d spent four years in the Marines but in the last few months had twice been hospitalized for mental illness. His family worried that he was suicidal. They hoped time with a war hero, a legend like Chris Kyle, might help.

It was a little after lunch on Saturday, February 2, when they picked up Routh and headed west on Highway 67. They got to Rough Creek Lodge around 3:15 pm. They turned up a snaking, 3-mile road toward the lodge and let a Rough Creek employee know they were heading to the range, another mile and a half down a rocky, unpaved road.

This was a place Kyle loved. He had given many lessons here over the last three years. He’d spend hours working with anyone who showed an interest in shooting. This is where he would take his boys when they needed to get away. In the right light, the dry, blanched hills and cliffs looked a little like the places they’d been in Iraq. When a group went out there, away from the rest of the world, they could relax and enjoy the camaraderie so many of them missed.

We may never know exactly what happened next. They weren’t there long, police suspect, before Routh turned his semiautomatic pistol on Kyle and Littlefield. He took Kyle’s truck, left Rough Creek, and headed east on 67. Later he would tell his sister that he “traded his soul for a new truck.” A hunting guide from the lodge spotted two bodies covered in blood, both shot multiple times.

Routh drove to a friend’s house in Alvarado and called his sister. He drove to her house where, his sister told police, he was “out of his mind.” He told her he’d murdered two people, that he’d shot them “before they could kill him.” He said “people were sucking his soul” and that he could “smell the pigs.” She told him he needed to turn himself in.

From there, Routh drove home to Lancaster, where the police were waiting for him. When they tried to talk him out of the truck, he sped off. With the massive grill guard, he ripped through the front of a squad car. They chased Routh through Lancaster and into Dallas. He was headed north on I-35 when the motor of Kyle’s truck finally burned out, near Wheatland Road. Routh was arrested and charged with two counts of murder.

• • •

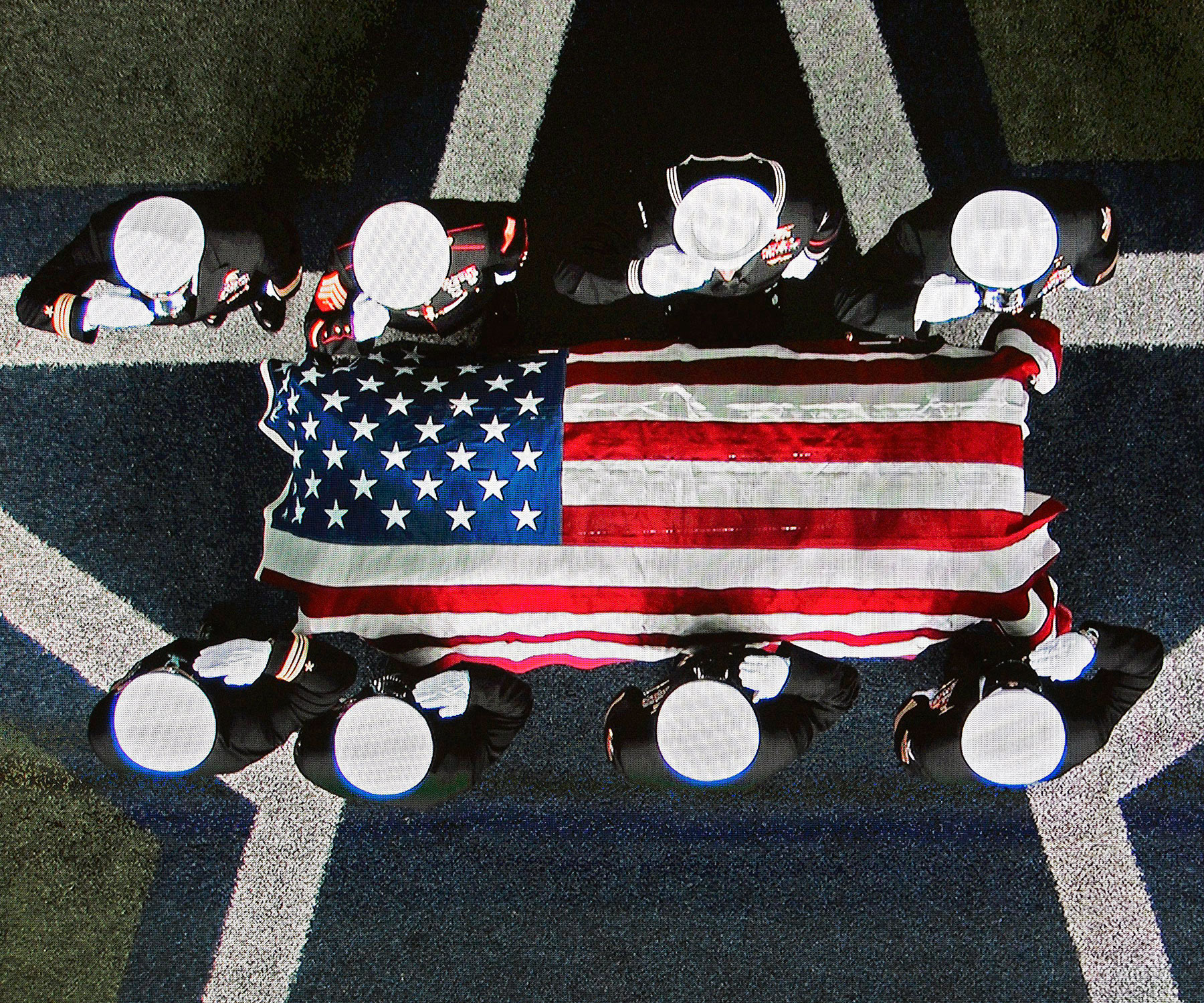

Plenty of people attending knew Kyle. But most didn’t. Some had read his book or seen him on television. Some had only heard of him after his death. Men missed work and took their boys out of school because they thought it was important. Families traveled from three states away.

Most people wore black. Many wore dress uniforms. His SEAL team was there, as were other SEALs and special-operations fighters from multiple generations. There were police officers and sheriff’s deputies and Texas Rangers. Veterans of World War II, some in wheelchairs, nodded to each other quietly as they made their way into the stadium. Some men had served in Korea, some in Vietnam, some in the first Gulf War. There were many servicemen who never served during a war and many people who had never served at all, but they all felt compelled to come.

Celebrities came, including Jerry Jones and Troy Aikman and Sarah Palin. Hundreds of motorcycle riders lined the outside of the field. Bagpipe players and drummers came from all over the state. A military choir stood at the ready the entire time.

A stage was set up in the middle of the football field. On the stage was a podium, some speakers, and a few microphone stands. At the front of the stage, amid a mound of flowers, were Kyle’s gun, his boots, his body armor, and his helmet.

Photos from Kyle’s life scrolled by on the gigantic screen overhead: a boy, getting a shotgun for Christmas. A young cowboy, riding a horse. A SEAL, clean-shaven and bright-eyed. In combat, scanning for targets. In the desert, flying a Texas flag. With his platoon, a fearsome image of American might. At home, hugging Taya, kissing the foot of his baby girl, holding the hand of his little boy.

His casket was draped with the American flag and placed on the giant star at the 50-yard line.

Randy Travis played “Whisper My Name,” and “Amazing Grace.” Joe Nichols played “The Impossible.” Kyle’s friend Scott Brown played a song called “Valor.” The public heard stories about what Kyle was like as a little boy. What he was like in training. What he was like at war. What he was like as a friend and business partner. Some people talked about the times they saw him cry. Fellow SEALs told stories about his resolve, his humor, his bravery. There were tales of his compassion, his intelligence, his dedication to God.

“Though we feel sadness and loss,” one of his former commanders said, “know this: legends never die. Chris Kyle is not gone. Chris Kyle is everywhere. He is the fabric of the freedom that blessed the people of this great nation. He is forever embodied in the strength and tenacity of the SEAL teams, where his courageous path will be followed and his memory is enshrined as SEALs continue to ruthlessly hunt down and destroy America’s enemies.”

Taya stood strong, surrounded by her husband’s SEAL brothers, and told the world about their love.

“God knew it would take the toughest and softest-hearted man on earth to get a hardheaded, cynical, hard-loving woman like me to see what God needed me to see, and he chose you for the job,” she said, her cracking voice filling the stadium. “He chose well.”

When the ceremony ended, uniformed pallbearers carried out the casket to the sounds of mournful bagpipes. Taya walked behind them with her children, hand in handThe next day, the casket was driven to Austin. There was a procession nearly 200 miles long—almost certainly the longest in American history. People lined the road in every town, waving flags and saluting. American flags were draped over every single bridge on I-35 between the Kyle home in Midlothian and the state capital.

• • •

People will tell stories about Chris Kyle for generations to come. Tales of his feats in battle, and of his antics and noble deeds, will probably swell. In a hundred years, people won’t know which stories are completely true and which were embellished over time. And, in the end, it may not matter too much, because people believe in legends for all their own reasons.

Since her husband’s death, Taya has been overwhelmed by the number of veterans who want to tell her that Chris Kyle saved their lives. A man with a 2-year-old girl wept recently as he explained that his daughter would not have been born had it not been for Chris Kyle rescuing him in Iraq. Years from now, men will still be telling stories about the moments when they were seconds or inches from death, when they thought it was all over—only to have a Chris Kyle bullet fly from the heavens and take out their enemies. They’ll tell their grandchildren to thank Chris Kyle in their prayers.

Because his legend is so large, because he personally protected so many people, there will surely be men who think they were saved by Kyle but owe their lives to a different sniper or to another serviceman. Of course, there will be no way to know for sure. Kyle credited his SEAL brothers any chance he could, but he also knew that he was an American hero, and he knew the complications that came with it.

During the interview in which he discussed the gas station incident, he didn’t say where it happened. Most versions of the story have him in Cleburne, not far from Fort Worth. The Cleburne police chief says that if such an incident did happen, it wasn’t in his town. Every other chief of police along Highway 67 says the same thing. Public information requests produced no police reports, no coroner reports, nothing from the Texas Rangers or the Department of Public Safety. I stopped at every gas station along 67, Business 67 in Cleburne, and 10 miles in either direction. Nobody had heard of anything like that happening.

A lot of people will believe that, because there are no public documents or witnesses to corroborate his story, Kyle must have been lying. But why would he lie? He was already one of the most decorated veterans of the Iraq war. Tales of his heroism on the battlefield were already lore in every branch of the armed forces.

People who never met Kyle will think there must have been too much pressure on him, a war hero who thought he might seem purposeless if he wasn’t killing bad guys. Conspiracy theorists will wonder if maybe every part of his life story—his incredible kills, his heroic tales of bravery in the face of death—was concocted by the propaganda wing of the Pentagon.

And, of course, other people—probably most people—will believe the story, because it was about Chris Kyle. He was one of the few men in the entire world capable of such a feat. He was one of the only people who might have had the connections to make something like that disappear—he did work regularly with the CIA. People will believe it because Chris Kyle was incredible, the most celebrated war hero of our time, a true American hero in every sense of the word. They’ll believe this story because there are already so many verified stories of his lethal abilities and astonishing valor, stories of him hanging out with presidents, and ribbing governors, and knocking out former football stars and billionaires and cocky frat boys.

They’ll believe it because Chris Kyle is already a legend, and sometimes we need to believe in legends.

Read more of the story in Mooney’s eBook: “The Life and Legend of Chris Kyle: American Sniper, Navy Seal.”