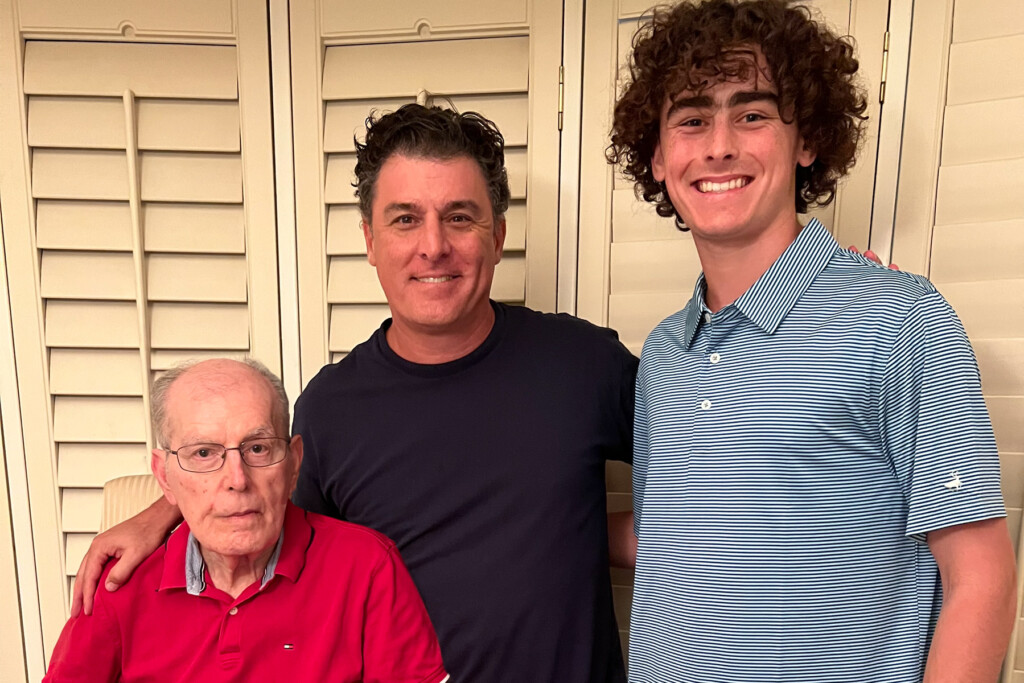

My dad died three weeks ago. His name is Al Newberg.

He is survived by his wife of 56 years, by three kids and four grandkids, and by pieces of himself, which, to varying degrees and in different ways, are built into each of us. One of them is sports.

Among my earliest memories are the every-Saturday trips with Dad to the Schepps convenience store at Midway and 635 for something out of the ice cream freezer. In 1976, at my suggestion, that ritual changed to a weekly pack of Topps. Baseball in the spring. Football in the fall. Cardboard gum bricks all year.

Dad didn’t collect cards. He wasn’t a star athlete. We didn’t go to games unless someone else invited us to tag along. But we never missed the Cowboys on TV, preseason through playoffs, and it was almost always with another family or two, along with tons of food. A reliable blast—and it didn’t hurt that the Cowboys were great in the mid-’70s.

That didn’t prevent Dad—and Mike, or Joe, or Harrell, or whoever we were watching the game with that weekend—from coming unglued if Efren Herrera shanked one wide right or Bob Breunig failed to wrap up the ball carrier on what turned into a 40-yard house call.

“Dad, c’mon,” I’d plead, not interested in deflating the fun. “He didn’t try to miss that tackle.”

But even if I didn’t realize it, I was learning a behavior. And a passion.

My final, futile objection to the intensity, with all its highs and lows, that Dad watched football with was lodged on one of those Saturdays as we pulled into Schepps. I remember this moment like it was Robert Newhouse taking the pitch left and winging a perfect 30-yard dime to Golden Richards for six.

“Dad, how many of the Cowboys do you know?” I asked, excited for whatever the answer was going to be.

“Personally?”

Yep.

“None.”

Wait, what?

“Then why do you care so much if they win?”

I remember the parking space we were in, but I don’t remember his answer to that question. I’m pretty sure, though, that it informed, inspired, authorized a new way that I was about to start clothing myself in sports. Investing that much intensity into sports—competing, training, watching, collecting, debating, caring—was OK. Because Dad did it.

As I said in my eulogy, in his final month, Dad asked me on every visit how the Rangers had done the night before. If it were football season, it’s a question he might have asked his caretakers. But even though baseball wasn’t his favorite sport, it was one of his favorite subjects with me. It was sports, after all — a gift he’d given me, a thing I learned to love by seeing him love it. A thing we shared. I fully believe Dad religiously asked last month if the Rangers had won because he knew if they did, that meant my own day was a little better. And that made it a good day for Dad.

Like most of my friends, I played every sport as a kid, but baseball is the one that really grabbed me. Dallas not having an NBA team probably made basketball feel more like a P.E. sport, and the Tornado weren’t on TV enough to galvanize me the way baseball did. I wanted to be Roger Staubach (even well after he retired, truth be told), but Mom wasn’t having that. So Robin Yount and Paul Molitor it was. (The Rangers’ post-Toby Harrah revolving door at shortstop was less inspiring.)

My first job was scorekeeping Little League games at Churchill or Northaven on the nights I wasn’t playing. I’d fall asleep listening to the Rangers on WBAP. I bought the Street & Smith’s Baseball Preview off the Taylor’s Bookstore magazine rack every February and subscribed to The Sporting News to read Peter Gammons and Joe Falls.

Baseball was mine. But first, sports were Dad’s and mine.

Now, and for the last 18 years, it’s my son Max’s, too. He played his final high-school baseball game five days ago. It was the culmination of 16 years of growing in the game—and through it. I know the feeling.

When I was about Max’s age, baseball went abruptly and unkindly from being a focal part of every day to … not. I still remember the playoff game that ended my career, two-thirds of my life ago, like it was last week.

Just as vivid is the memory of getting home after the bus ride back to the school and the talk through tears with Dad and Mom, about a season that had ended sooner than wanted and the shock of accepting that there was no next game, no next season. Wrapping heads around all of the successes, the adversities, the matchlessness of team, and the rewards of pushing through.

My wife and I might have had a similar conversation with Max a few nights ago.

But I’m not able to tell Dad about Max’s final game. He would have liked to talk about it. I would have liked to talk about it. Sports was language for Dad long before baseball was vocabulary. He missed no more of the 250 games I played than I did of the 500 Max played. Decades later, there was a time when a seat at Max’s games and at the theater performances of my daughter, Erica, were givens. Parkinson’s Disease gradually made attendance less frequent, but the recaps were automatic subject matter.

Not anymore, though. I already miss it. A lot.

I was reading something the other day to help me process the erratic introduction of grief that Dad’s death has brought on. One sentence stuck out: “All deaths occur in the middle of a conversation.” I don’t think Anne Brener had my son’s high school games or the Cowboys’ playoff chances in mind when she wrote that, but for me, there were two constants in my conversations with Dad, especially in the last year as his cognition began to soften: the latest on what my kids were up to, and sports. Often, those two things fused. We were still in the middle of that conversation, one that started gaining a lifetime of momentum 50 years ago in a convenience store parking lot.

Will baseball remain in Max’s life, in some form, just as it has for me? “Strong yes” is my guess, if we’re taking bets. He has a passion for the game and its nuances, and it already has rewarded him on so many levels. I won’t sit here and declare that the game is in him simply because the game is in me; baseball wasn’t really something my father handed down to me, after all, and I still found my way to it. But I’m pretty sure there’s a predisposition that made its way from Dad to his only grandson. Max doesn’t call me out for voicing my irritation at a big-league bullpen meltdown or a personal foul on third-and-long, like I would have with Dad, but I have a pretty good idea what he’s thinking from the other end of the couch. Because I remember being that kid, processing and judging my own father’s overreactions to bad sports moments, before I adopted the character flaw myself (and, admittedly, took it to a new level).

At Dad’s service, I shared a few lines that Bono wrote in a song for his own dying father 20 years ago:

Can you hear me when I sing?

You’re the reason I sing

You’re the reason why the opera is in me

I explained that my opera, one inherited from Dad, is to be there for my family. That family is everything.

It was only in the interest of time that I didn’t add there is clearly a second opera, handed down by example from Dad, that was hardwired in me at an early age: the allure of sports. The emotional swings and the drama. The artistry. The brand loyalty. The goals, the dreams. The adversity and the response and the virtual perfection of the idea of team.

I think it’s probably in Max, too. The path has been different, but the destination the same. In whatever new forms it’s bound to take.

Author