The following is an excerpt from Dr. Brian Williams’ The Bodies Keep Coming. It was published in the September issue of D Magazine.

Four days after the shooting I stood in a secluded corner of the hospital, my forehead buried in one hand and my cellphone cradled in the other. “Brian, you have to go,” Kathianne pleaded. “This country is tearing itself apart.”

Parkland had scheduled an afternoon press conference, a chance to describe the hospital’s response to the mass shooting. Since I was the trauma surgeon on call that night, leadership expected me to attend. My wife was trying to convince me to do what I never wanted to do: talk to the media. I had mastered avoiding the media, declining nearly every request over the years. I didn’t have an active social media presence, and interviews were never my thing. This particular press conference meant recounting the most traumatic night of my career; live, in front of microphones, cameras, and strangers.

I had worked hospital shifts every day since the shooting. Each day I donned a clean white coat and spent another day at Parkland Hospital rounding on patients, teaching students and residents, and fixing people in the operating room. The day after the shooting, I even attended a disco dance party for my daughter’s preschool friends and their parents. I was doing what I did best: compartmentalize, work, and soldier on.

I was also on a self-imposed media blackout: no television, radio, newspapers, or social media. The dominant news story was 7/7, and I wanted none of it.

“Just go so people can at least see you,” Kathianne said. “The world needs to know that it wasn’t just a Black man who shot those cops but that a Black man also tried to save them.”

She paused to let it sink in.

“You don’t even have to say anything. Just show up. Being there will make a difference.”

She had a point. A divided nation reeling from another mass shooting needed to see that a Black doctor had been in charge, trying to do the right thing. In this story, not only the villain but some of the heroes were Black. Maybe just showing up would speak volumes without me opening my mouth. Besides, Kathianne was insistent.

“The country needs to see you. You’re the only person in the world with this experience: a Black trauma surgeon who tried to save the white police officers shot by a Black man because of racist policing. I mean, come on.”

She was relentless. Still, I felt reduced to something I had worked my entire life to avoid: being the token. A Black face present for the optics. I stared at the floor, computing the risk-benefit ratio. I’d be crazy to go, I thought; the risks far outweighed the benefits.

“Kats, I have to get back to work,” I tried to sound nonchalant as nurses, doctors, and visitors passed within earshot. “I’ll talk to you later.”

Being married to someone who does not give up can be a blessing and a curse. Kathianne’s tone shifted, assuming an urgency I rarely heard from her.

“If not you, Brian, then who?” she demanded.

(Anybody but me, I thought.)

“And, if not now, then when?”

(Never, and I was fine with that.)

The forcefulness of her speech gathered momentum. “This is bigger than you. You have to be there. You have to show up, Brian. Step into the arena!”

Per her insistence, we were both reading Brené Brown’s Daring Greatly at the time, and the phrase “step into the arena” had become her mantra. Then Kathianne brought the spiritual heat: “That night, you were exactly where you were supposed to be. God put you there for a reason.”

She should have stopped before invoking God, which is not a great strategy for convincing a faith-avoidant person like me to do anything. I had long grown weary of the stories told by white men about a white God and the celestial exploits of white people. I saw no place for a Black man like me in those timeless fables of redemption and salvation. God bless America? When neither God nor America seemed to value Black people? Please. When Kathianne said God put me there for a reason, my eyes rolled so far in the back of my head I nearly broke an ocular muscle.

Still, she was right: I should go. I didn’t fully accept her logic, but I surrendered—not to any faith, but to my duty. This was about Black representation. I’d say nothing, just be present. I’d sit before the cameras, keep my mouth shut, look professional, and satisfy everyone. It was an act I had mastered over the course of my entire medical career. No confrontations. No controversy. No fuss. Get along to move along. And after the press conference I could shrink back to my life of comfortable anonymity.

“OK. I’ll go,” I relented. “But if I speak, I’ll lose it.”

“Even if you do lose it and the world comes crumbling down, I will stand by you.”

Given the preceding years of our withering marriage, that was a truly incredible thing for her to say. Although I trusted her and had told her more than anyone else in my life, I still kept her in the dark about my deepest thoughts.

“Let me know how it goes. Remember, God put you there for a reason. I love you.”

“I love you, too.”

Minutes later, when I joined my colleagues gathering in the hallway outside of the conference room, a man walked past holding a television camera emblazoned with the CNN logo. The minimal enthusiasm I had for the press conference evaporated, and I sent a final, desperate text to Kathianne.

No response. Having invoked God one last time, she went to the gym for a workout. After her incessant prodding and proselytizing, she had no plans to watch. In fact, we both assumed it was nothing more than a small, local press conference.

How wrong we both were.

Marching in a single file, six of my colleagues and I faced a phalanx of lights, cameras, and reporters. I ignored the murmuring amid the clicks and flashes and shuffling notepads. Like marching in formation at the Air Force Academy, I caged my eyes on the back of my partner, Dr. Alex Eastman, leading a few feet in front of me. Five more senior hospital leaders were in line with us.

The seven of us were chosen to represent Parkland and describe the hospital’s response to one of the defining mass shootings in U.S. history. As we filed into the conference room and took our seats at a rectangular table lined with microphones, I tried to ignore the standing-room-only gallery of attendees. So many people filled the room that some sat cross-legged on the floor mere feet in front of us.

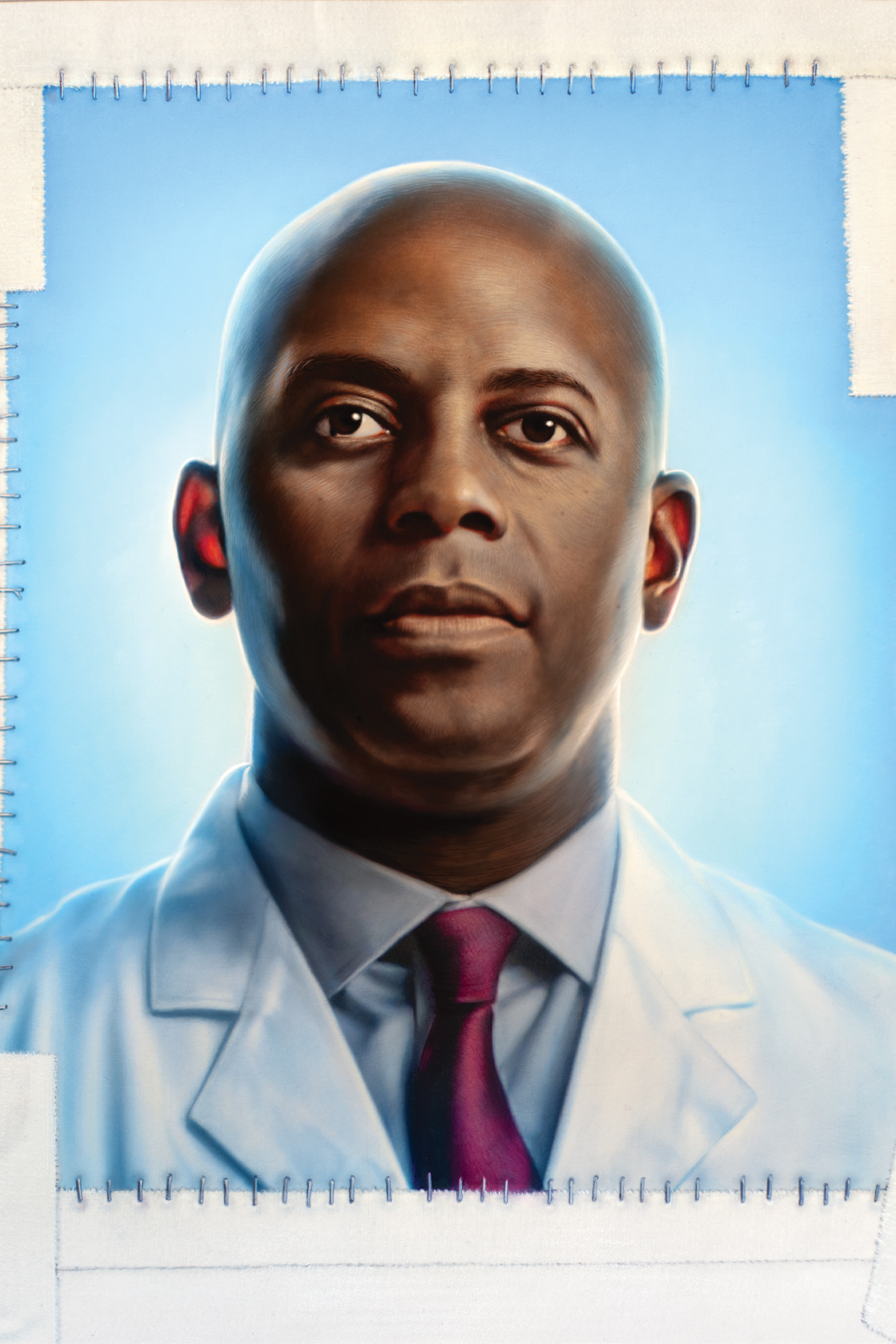

Some of my colleagues wore black athletic jackets with the Parkland logo. I wore the white coat issued to every doctor on faculty at the medical school across the street. On the left breast of mine were two lines embroidered in blue—Brian H. Williams, MD, Trauma/Critical Care—and on the right was the logo of the university and our employer, UT Southwestern. The white coat was my armor and résumé, gleaming white and razor sharp for the world to see. Unlike me, my partners likely never had a patient ask them to take out the trash, or clear their meal tray, or call for their “real” doctor. If my role in this press conference was to be seen by white America, then I would leave no doubt that I was anything but a respected surgeon. Especially since I was the only Black person at the table.

I struggled to remain mentally present. I half-listened to the designated spokesperson, while the rest of us could choose to speak or remain silent. He began reading from a prepared statement summarizing the incident with sterile phrases: multiple shooting victims, critically injured, disaster response. The words sounded cut and pasted from the reports of other recent mass shootings.

At first, I barely paid attention, my mind replaying the bloody loop of the tragedy four nights prior. But occasionally the language of the official statement pierced my attention. As I began to listen in, what was unsaid was impossible to ignore. In the official statement, race was never mentioned. It was as if the shooting had happened in a vacuum-packed, sealed-off place with no history. No context.

Unbelievable, I thought. That’s all he has to say? What about Alton Sterling and Philando Castile, Black men killed by police less than a week earlier? What about the larger context into which this tragedy had landed: the shooting at a gay nightclub in Orlando less than a month earlier? The presidential election with bigotry, intolerance, and violence on proud display? It was clear to me 7/7 was not an anomaly; it was the predictable result of America’s refusal to reckon with her legacy of racism. A Black sniper had shot white cops at a protest for racial justice, and not a single person named the trumpeting elephant in the room. No one at this press conference—not my colleagues beside me nor the reporters asking the questions—was making any connections.

So there I sat, stone-faced, like a child forced to sit through church. Mentally adrift, I tried to hide in plain sight, eyes caged on the table. I ignored the cameras lining the back wall and the reporters sitting cross-legged on the floor, so close I felt I could have nudged them with my foot. I ignored my colleagues at the table, those who often professed they “didn’t see color”—and who therefore didn’t see what 7/7 meant to me. As I slumped and pouted and stared, the whitewashed description of the shooting continued.

I was the mute trinket in a clean white coat playing my part: to be seen, not heard. To maintain everything I had achieved and to continue rising, on a semi-conscious level, I knew I had better stay in my lane. It was a reality I’m certain that my colleagues, pontificating in turn at the microphone, could not comprehend. I began to shift in my seat. I had spent a lifetime hiding my opinions and keeping my head down. But by remaining silent, I’d be giving tacit approval to a disingenuous narrative: one that deified the cops, vilified the killer, and nullified America’s history of terrorizing Black people. But if I said what I felt—what I truly felt—I would most likely be fired.

As the microphone slid to me, I reached for it as if it were a cobra about to attack. I audibly exhaled, considering one last time if I truly wanted to do this.

“I want to state first and foremost, I stand with the Dallas Police Department,” I began. A scratchy lump in my throat halted my words. “I stand with law enforcement all over this country. This experience has been very personal for me and a turning point in my life. There was the added dynamic of officers being shot.”

The words flowed freely. The persona I had molded and polished for public consumption was displaced by this rogue entity who now commanded my actions.

“We routinely care for multiple gunshot victims,” I said. “But the preceding days of more Black men dying at the hands of police officers affected me. I think the reasons are obvious. I fit that demographic of individuals.”

My lips quivered and my voice thickened. Yet I could not turn off the spigot of words that continued to flow without end. In that moment, there were no cameras, lights, or people. No table, chairs, or walls. Nothing. Just me and the mic.

“But I abhor what was done to these officers, and I grieve with their families. I understand the anger and the frustration and distrust of law enforcement. But they are not the problem. The problem is the lack of open discussions about the impact of race relations in this country. And I think about it every day: that I was unable to save those cops when they came here that night. It weighs on my mind constantly.”

By this time, I was choking back tears and barely able to talk. “This killing, it has to stop: Black men dying and being forgotten, people retaliating against the people who are sworn to defend us. We have to come together and end all this.”

I didn’t know what I was going to say until I said it. But suddenly it seemed like my whole career as a Black trauma surgeon—operating on patients, some who revered me and some who reviled me—had slid toward a pointed, jagged edge. In a room packed with people, likely watching me set fire to my career, I felt completely alone. And yet, for the first time in as long as I could remember, I was at peace.

Questions soon came my way, and I did my best to answer them. One reporter asked about my relationship with law enforcement. In a flash I thought of all the incidents I could share: being forced to stand spread-eagle over my hood for going six miles an hour over the speed limit, being asked for my ID for standing outside my apartment building. Instead, I talked about trying to set an example for my 5-year-old daughter, about the times I bought meals and ice cream for police officers when we were out and about in Dallas. I wanted to model for my daughter how to show kindness and respect in a system that might view her as unworthy, or worse, a threat.

I had already broken several unspoken pacts: when we talk about tragedies, we don’t talk about racism. When shootings occur, we offer thoughts and prayers and move on. We don’t look at the tragedies unfolding in emergency rooms across the country as having anything to do with the tragedy of a system that privileges some and disadvantages others.

And, most importantly, the Black guy smiles, nods, and keeps his damn mouth shut.

Maybe I’d lose my job, but I would no longer hand over my dignity and self-respect pretending to be something I was not. So I took a deep breath and said to the police officers in the room and around the country: “I support you. I will defend you. And I will care for you. That doesn’t mean that I do not fear you.”

Finished, I pushed the microphone away, leaned back in my chair, and thought: Oh shit, what have I done?

At the gym, Kathianne was well into an elliptical machine workout when the wall of high-definition television monitors flipped from the regularly scheduled programming to the press conference. On national television was a larger-than-life image of me—crying. She hopped off her machine and recorded the soundless images with closed captioning. My unscripted comments, broadcast on media outlets around the world, soon went viral on social media, and interview requests soon overwhelmed the hospital switchboard.

Meanwhile, I was oblivious, having no idea what transpired beyond the confines of the conference room where I sat. Eager to slip out of the spotlight and ease back into anonymity, I stood from the table and turned to leave. Suddenly and without warning, Dr. Eastman wrapped me in a bear hug. Cameras from a sea of photojournalists trained on this duo, capturing an image of camaraderie that was discordant with reality. I responded with a perfunctory bro hug pat on the back and tried to inch away. But he held his embrace while whispering into my ear some platitude about brotherhood. When I finally disentangled myself, I left the conference room alone, unaware I was entering a media tempest.

“Dr. Williams, we have several reporters who would like to speak with you.” It was Bret from media relations. “And they’d like some photos, too, so, if you have time, we can set you up in one of the trauma bays. Do you mind doing it?”

From behind, the reply came from Dr. Eastman. “Of course, we can do it, Bret. Where do you want us?”

“Uh, they just want Dr. Williams,” Bret replied.

A handful of eavesdropping nurses snickered. Some said that the most dangerous place to be is between Dr. Eastman and a camera, and I had stumbled into his spotlight.

As the media relations team arranged the trauma bay, I did a couple of interviews in the hallway outside the conference room. First came the Dallas Morning News, followed by the Washington Post, the Daily Mail, and the Associated Press. Later a well-known opinion writer from the New York Times who saw the press conference wrote about it as well.

And the following day, the photograph of “the hug” ran on the front page of the Dallas Morning News (the accompanying story was a Pulitzer Prize finalist). Here was apparent evidence of the heartwarming story many people longed for: the unique fraternal bond between two doctors, one Black and one white, forged on the frontlines of tragedy. Except it wasn’t true. Eastman had not been at the hospital that night.

It wasn’t the only photograph telling one story while I lived another. That same day, dressed in my white coat, shirt, and tie, I was one of dozens of mourners downtown, paying respects at the impromptu memorial that had grown over the preceding days outside of the Dallas Police Department headquarters. The centerpiece was a DPD cruiser buried beneath a mountain of flowers, photos, placards, and cards. I made small talk with a pair of officers who thanked and hugged me as we shared words of comfort. I stopped to read the handwritten sentiments and study the oversized headshots of the slain officers. Media trucks with satellite antennae pointed skyward lined the street, and reporters performed visual and soundchecks with their crews. Trying not to be distracted, I noticed that where I walked, the cameras followed.

Ever since I’d cried in the hallway the night of the shooting, it was like some switch had flipped within me. Emotions left over from the tragedy—a stew of anger and shame and grief from my inability to save officers Zamarripa, Krol, and Smith—overcame me, and my tears started to flow. I began to ease into a crouch to gather my thoughts and emotions as privately as I could in a public space. But I never made it to the ground.

From behind, two paws slammed onto my shoulders and whipped me around until I was face to face with Dr. Eastman. Now crying harder, I pushed him away. I wanted my space. I needed my space. But I sensed that he wanted something also, and he seemed determined to get it. He pulled tighter, wrapping me in his arms as I, crying convulsively, gave up the fight. What was his deal? This was supposed to be my time to pay my respects—alone. My time to grieve—alone. And there he was, once again, drawing me into another one of his photo ops.

But I would not make a scene beside a public memorial honoring dead police officers. That would be disrespectful to them, their families, and the other mourners. I most definitely would not make a scene in front of all those cameras, several of which were now focused on this manufactured display of brotherhood. Under no circumstances could I make a scene even if I wanted to do so. Because I’m Black, and that is just not allowed.

Finally, he released me.

Simmering beneath my visible grief, my fury intensified. Twice in less than one week I allowed myself to serve as a prop in the media circus. Both times I let it happen. Both times I said nothing. And both times I emerged embarrassed and enraged. It was far from how I assessed what truly existed between us and presented what I felt was a false narrative. Dr. Eastman shared the photo widely with the caption “The Essence of Brotherhood.”

Those photographs and words like this—we’re all the same, we come together—became the foundation for a revisionist history with a life of its own. I suppose I could have halted the storyline as it developed. But there were dead police officers and grieving families, so I said nothing. No matter how many times I was asked, I never revealed more than necessary. When it was showtime, for the media, at speaking events, and at work, I knew how to mask my true feelings with an Oscar-worthy performance.

We, the aggrieved, become accomplices through silence and self-censorship. By not being the spokesperson for our own stories, we allow history to be rewritten. When we don’t speak up—and sometimes even when we do—someone else can pose as the expert on our story. In the words of author Zora Neale Hurston: “If you are silent about your pain, they’ll kill you and say you enjoyed it.” Which is worse: to speak and have our truths demeaned, distorted, and dismissed, or to choose a self-imposed silence?

Looking at those photographs, you would have no idea what I actually felt. There was no way for a viewer to know how I sensed those hugs were less a symbol of interracial friendship or heroic bond and more a metaphor: for all the ways Black people get engulfed by whiteness, all the times we get wrapped in its clutches.

In the coming days I went where I was directed and did as I was asked. Reporters and producers wanted to hear from “that Black trauma surgeon from Dallas.” Within 24 hours of the press conference, I had done interviews for local, national, and international news outlets including CNN, Fox, CBS, ABC, BBC, the New York Times, Associated Press, Dallas Morning News, and more. Then the morning after the press conference it was live interviews on CNN, Fox, and CBS with Gayle King, which placed me one degree of separation from my wife’s idol, Oprah Winfrey.

That evening I did a late-night interview on CNN with Don Lemon. Since I didn’t watch cable news shows, I was unaware of his reach and influence. Sitting in a local studio in my white coat and scrubs, as directed by the hospital media team, I took the earpiece from a technician, looked toward the camera, and did a sound check. That was the extent of my preparation to be interviewed by the host of one of the highest rated cable news shows in the country. I had received no media training, developed no talking points, and had no prepared remarks. I did my best to answer questions posed by this seasoned journalist about one of the defining tragedies in the history of Dallas and U.S. law enforcement. “What do you want to say, Doctor?” Don Lemon asked. “The world is listening.”

I lost it—again. A convulsive, crying mess on prime-time cable television.

Mine wasn’t the only Black face of 7/7 telegraphed around the world. In addition to me there was the shooter, Dallas Chief of Police David Brown, and another Black man whose life intersected with this story: Mark Hughes.

Mark Hughes had gone to the rally with an assault rifle strapped to his back, exercising his second-amendment and state-protected right to openly carry a firearm with a license. Police officers had detained him as a possible suspect and removed his weapon. Hughes was questioned, released, then detained again. His face was broadcast everywhere, initially identified as a “cop killer.” In the aftermath, Hughes received death threats, his small business disintegrated, and he had to move to another city for his own safety. Despite the fact that the real killer was dead and that Hughes had had absolutely nothing to do with the killing, he never received an apology from the city or exoneration in the press. Six years later, as I write this book, he still hasn’t.

One year after the shooting, Mark and I met for lunch at a family-owned barbecue restaurant. We could have talked for hours had work not demanded his presence, and a promised trip to get ice cream with my daughter had not demanded mine. Still, as we ate, Mark and I unpacked issues of social justice, institutional racism, gun rights, and what it meant to speak truth to power.

“Yeah, I saw your press conference when it happened,” Mark told me. Barbecue sauce pasted his fingers, which he sucked dry with lip-smacking satisfaction. He wagged the remnants of a pork rib at me for emphasis, his voice muffled by cheeks full of meat. “We was watching the TV, and I turned to my brother and said, ‘That man right there: he’s about to catch hell.’ ”

This excerpt originally appeared in the September issue of D Magazine with the headline, “The Wounds of a Surgeon.” After D Magazine arranged to publish this excerpt, Williams announced his candidacy for Texas’ 32nd Congressional District. His campaign focuses on gun reform. Write to [email protected].